Introduction: Heading Off Potential Problems At The Pass

When one company acquires some or all of the assets or divisions of another, the acquirer faces a recurring set of issues related to electronic information management. Whether the transactional context is a merger or asset purchase, there are many moving parts and traps for the unwary. Along with physical items, goodwill, employees and other contemplated elements of the transaction, typically the target has a mountainous set of electronically stored information (ESI) that needs to be pored over in the due diligence process.

Some or all of that ESI ultimately needs to be marshaled – to facilitate efficient operation of the acquired business and fully functional use of the assets. This information can include the target's accounting and tax records, documentation related to its products (and possibly the products themselves, if software is involved), personnel records, copies of relevant contracts and related negotiating history, intellectual property records and pleadings and discovery data from ongoing litigation.

Forethought is necessary to ensure the acquirer and its counsel follow best business practices and comply with legal obligations. These issues exist throughout the life cycle of the transaction and onward through the post-closing operations. Many key considerations come to the fore during the gathering, retention and storage of pertinent parts of the target's vat of electronic information. If an acquisition were a rodeo, these three key aspects would be the wrangling, lassoing and roping events.

I. Data-Wrangling To Speed The Deal

On the "gathering" front, uploading electronic files to web-based virtual deal rooms is an essential tool. This type of workspace makes the target's information and documents electronically accessible for due diligence and transfer upon acquisition. These rooms – called "ShareRooms" at the authors' firm – enable participation by any player in the deal, from any location around the globe. Each lawyer, officer, manager and accountant – and their designated staff members – can simply use a web browser and a login/password to upload, review, comment on and pose questions as to diligence documents.

A law firm's ability to offer secure websites where clients and counsel and other approved participants can access transaction-related documents and resources was once a significant market differentiator. In the last several years, these ShareRooms or "extranets" have become increasingly commonplace.

Virtual deal rooms' benefits are many and well known, as evidenced by the diligence process for a recent acquisition. This deal involved – just counting law firms on the target's side – special transaction counsel in California, corporate counsel in New Jersey, separate intellectual property counsel in New Jersey, and a fourth firm defending the target's pending patent litigation. On the acquirer's side were in-house lawyers, an in-house business development team, outside counsel and separate IP counsel.

Use of a ShareRoom allowed for a one-location surf-able and searchable archive, with varied levels of access rights for respective categories of participants. It also made possible asynchronous workflow without the need for a face-to-face meeting or any other direct, real-time communication. This process, in turn, allows for increased participation in the process, and negates geographic limitations. The upshot is that deals go much faster, and at a reduced cost to the client.

Although adoption of extranets in transactions is nearly universal, vast differences still exist among firms in terms of the ability to efficiently provision and administer them. A majority of firms outsource the provision and management of their extranets to Application Service Providers (ASP). Outsourcing is by no means a necessity; and firms that are able to bring this function in-house gain greater control over features and the ability to reduce client costs. First, firms that manage the process in-house simply cut an additional third party vendor out of the picture. Because the firm's business is its legal advice, it can essentially price its extranet at or very close to cost with little impact on its usual model.

The authors' firm went out on a limb a number of years ago; and, ever since, it has generated and administered its own extranet platform. The positive consequences have included:

- the ability to manipulate malleable platforms to fit the

contours of particular deals;

- re-use of popular, deal-tested "template"

folder-sets to avoid reinventing the wheel;

- increased – and upbeat –

collaboration between lawyers and IT staff within the

authors' firm; and

- ultimately, "stickiness" with pleased clients,

who return for additional efficiently managed deals.

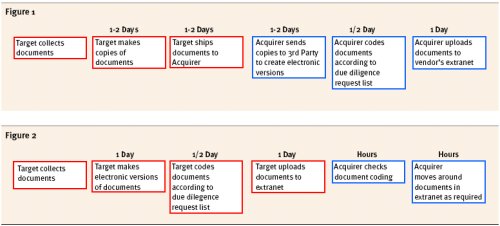

At the heart of the happiness with the in-house hosting operation is its significant reduction of the time between the target's document collection and the analysis of pertinent information. In a typical third-party vendor scenario, counsel transmits a diligence request to the target, usually as a Word or .pdf attachment to an e-mail message. The target locates the requested documents, often in hardcopy form, and then provides copies to the acquirer. The acquirer sends them on to the vendor, which scans them into electronic format and then either: populates the extranet with them; or returns them to the acquirer for coding, according to the diligence request list, followed by upload to the extranet. Even under typical transactional time-pressure, this process can take at least 4½ to 7½ days (See Figure 1 Below).

In-house control allows the law firm to integrate its diligence needs and law-practice dictates with the site itself. In acquirer representations, instead of transmitting a separate document containing diligence requests, the acquirer's requests are built into a tailored site. The target is then sent an e-mail, with a link to the requests, which each has an associated field for uploading responsive documents in electronic form. As to any documents existing only in paper format, the target scans and uploads them. Turnaround time for the process can frequently be reduced to less than three days (See Figure 2 Below).

As alluded to above, extranets' contours can be adapted in-house to fit the firm's – and its clients' – respective review processes. A manipulable platform meets the frequent need to slice diligence materials into information categories that match representations and warranties in the deal documentation. This goal is achieved by associating fields with the diligence documents, which, in turn, allows reviewers to quickly identify and describe diligence issues in a location that is both centralized and attached to the source document. The information from these fields can then be aggregated automatically into a diligence report addressing various areas of concern.

Although developing in-house extranet expertise takes some significant initial resource commitment, that approach has proven worthwhile to our corporate colleagues, as described above. Useful jumping off points are in the following articles: Gerow, Mark, Marshaling Firm Resources With SharePoint; How to integrate Microsoft Office SharePoint Server 2007 with legal line of business applications, Law Technology News ( Jan. 2008) http://www.law.com/jsp/legaltechnology/pubArticleLT.jsp?id=1200594607309; Gerow, Mark, Implementing Large-Scale Extranets, Law Technology News (Nov. 2007) http://www.law.com/jsp/legaltechnology/pubArticleLT.jsp?id=1195207452210.

In either scenario – in-house or ASP – ideally as much information as possible should be gathered in native electronic formats rather than in paper form. However, there are some factors that, in the trenches, still militate toward the continued vestigial reliance on paper. These factors include:

- Many organizations do not have paperless or

electronic-signature regimes in place. Thus, many lawyers,

paralegals and others worry that they are not getting the

final drafts of pertinent documents unless they obtain a

hardcopy that includes a physical signature page.

- People are creatures of habit and have become used to

scanning, then converting to searchable text via Optical-

Character-Recognition (OCR) software and then coding, even

though those steps add much time and expense to the

process.

Still, the current state of the art – often a "semi-high-tech" approach is an improvement on the old days. As to ultimately achieving an even more high-tech approach, the future holds promise on at least two fronts.

-

Concept Search. Using concept search tools –

already somewhat widely deployed in the litigation

context—to speed and focus the diligence process,

appears to be an impending development.

- Content searching of legal documents presents a

specialized set of problems, however; and there remains

significant work to be done before these tools can be

efficiently implemented.

-

Searching legal documents, one is typically looking for

short passages of important operative language that

will affect: the disclosure against a representation in

a deal document; the need for third-party consents;

termination requirements; or other matters affecting

the value of the target or of the relevant assets.

Although the passage may have huge practical impact for

the transaction, most times it will:

- (1) only occur once; and

- (2) use of language very similar to the content

of many other legal documents of the same

nature.

- (1) only occur once; and

- Content searching of legal documents presents a

specialized set of problems, however; and there remains

significant work to be done before these tools can be

efficiently implemented.

This phenomenon contrasts sharply with, for example, web searching. Because of the highly differentiated content of the web, searching by frequency of incidence of a concept is a fairly effective way of generating pertinent information. Modifying concept search tools to reliably identify legally significant language is the next challenge.

-

Data-delivery to the acquirer. A convenient tool for the

client post-consummation of the transaction is a searchable

database of deal and diligence documents.

- The pertinent information can be pushed into the

acquirer's existing databases using tab delimited

or comma delimited files. These file types do require

humans to manually ensure that the file information

properly integrates with the existing database.

- Further development is needed to routinize the use of

Extensible Markup Language (.xml), which is machine

readable and does not require such intervention.

Documents are keyed to xml headings, which import

automatically into the acquirer's existing

respective database. Clients already use .xml in other

areas of their businesses, such as facilitating

coordination of vendors in their supply chain. Expansion

to transactional contexts is ostensibly a small and

impending step.

- The pertinent information can be pushed into the

acquirer's existing databases using tab delimited

or comma delimited files. These file types do require

humans to manually ensure that the file information

properly integrates with the existing database.

As to adoption of markup language, public company clients have gotten a push in this direction by the SEC, albeit with a different language. Over the last several years, the SEC has pushed heavily for voluntary adoption of Extensible Business Reporting Language (XBRL) for financial reporting. XBRL, like .xml, allows businesses to tag financial information in a way that makes it easily manipulable by machine.

In May of this year, the SEC proposed a phased implementation for XBRL. See News Release 2008-85, SEC Proposes New Way for Investors to Get Financial Information on Companies (May 14, 2008) http://www.sec.gov/news/press/2008/2008-85.htm. The "Interactive Data" rule requires use of XBRL after December 15, 2008 by companies having a market capitalization of more than $5 billion and using U.S. GAAP. SEC Release No. 33-8924 (May 30, 2008) http://www.sec.gov/rules/proposed/2008/33-8924.pdf. The new rule also establishes a goal of full implementation by 2011. See generally Aguilar, Melissa Klein, SEC Wants Quick Action on XBRL, Compliance Week (June 10, 2008) http://www.complianceweek.com/index.cfm?printable=1&fuseaction=article.viewArticle&article_ID=4188.

Widespread use of XBRL will provide its own benefits in the public-public merger context, facilitating integration of financial data in the combined entity.

II. Data-Lassoing To Safeguard Information Assets Subject To Business Needs And Legally Imposed Retention Obligations

Putting aside dreams of future automation, in the current data-laden world, there are three key arenas beyond due diligence management in which an acquirer can benefit greatly from EIM "pre-planning" in the post-signing and post-closing phase of an acquisition:

- information a business needs for smooth transition and

efficient operation of the now-bigger successor

company;

- information required to be retained to assure regulatory

compliance; and

- information already subject to an existing

litigation-hold or that should become subject to a litigation

hold.

Without advance planning, the problems for the client acquirer are compounded in these areas in that target's transaction counsel tends to disappear once the deal is consummated. Retention issues for the target in an asset purchase, for example, may be left up to whoever is in charge of liquidating the remaining assets. Similarly, on the acquirer's side in any transaction, such concerns will fall in the lap of the person(s) charged with integrating the acquired company or assets into the acquirer's business.

In most situations, the common denominator is that ESI management and maintenance issues are only occasionally brought to outside counsel's attention in a prophylactic way.

A full discussion of all those areas of concern is beyond the scope of this piece. Assuming that "business-needs" information already has some visibility to transaction counsel, this section will focus on what may be a rare beast to some business lawyers, namely the "litigation hold." This wild stallion sometimes goes by the moniker "preservation obligation" or "purge suspension duty."

Modern-day judges treat with utmost seriousness the duty to preserve potentially relevant information. Once a dispute merely ripens to the point where litigation is "reasonably anticipated," there is a "duty to suspend any routine document purging system . . . and to put in place a litigation hold to ensure the preservation of relevant documents – failure to do so constitutes spoliation." Rambus, Inc. v. Infineon Technologies AG, Inc., 222 F.R.D. 280, 288 (E.D. Va. 2004). See generally The Sedona Conference, Commentary on Legal Holds; The Trigger & The Process (Aug. 2007) http://www.thesedonaconference.org/content/miscFiles/Legal_holds.pdf. See also Robert D. Brownstone; Destroy or Drown – eDiscovery Morphs Into EIM, 8 N.C.J. L. & Tech. (N.C. JOLT), No. 1, at 1, 15-19 (Fall 2006) www.ncjolt.org/images/stories/issues/8_1/8_nc_jl_tech_1.pdf.

If a civil lawsuit does ensue, the consequences of lack of compliance with a litigation hold obligation can be dire, including: monetary penalties (such as attorney fees, costs, and/or pay-for-proof sanctions); exclusion of evidence; delay of the start of trial; mistrial; adverse inference jury instructions (presuming that any and all deleted information must have been harmful); and, in an extreme case, a dismissal or judgment on the merits. Id. at 16-18.

When an acquiring company's counsel does its due diligence, it should thoroughly examine the nature and extent of any actual – and reasonably anticipated – lawsuits. In some situations more than others – depending on the particular companies, industry and timing – that due diligence assessment may have more of an impact on the deal's contours.

In a stark way, both the importance and complexity of properly executing litigation holds are illustrated by Bank of America's recent acquisition of Countrywide Financial. MarketWatch reported that BofA made the acquisition at a bargain price, equal to less than a third of Countrywide's book value – and a reduced multiple of forecasted earnings. Barr. Alistair, B. of A. gets a bargain in Countrywide deal; Banking giant also taking on new credit, legal risks, analysts say, MarketWatch (Jan. 11, 2008) http://www.marketwatch.com/news/story/b-gets-bargain-countrywide---/story.aspx?guid=%7b82BACC3B-A5A8-4A52-9916-05460F95E349%7d&print=true&dist=printTop. Whether that price turns out to be a bargain in fact, however, will depend heavily on the outcome of pending and likely future litigation against Countrywide regarding its subprime lending practices, as well as the extent to which losses can be mitigated through foreclosures. How the successor fares in those proceedings, in turn, will depend in part on how well pertinent records are managed during the transition.

The duty to properly issue and maintain a litigation hold is not just part and parcel of an M&A deal. It reaches across the transaction, and even through bankruptcy, as illustrated by a recent case. In re NTL, Inc. Sec. Litig., 2007 WL 241344 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 30, 2007) involved a Defendant company that had filed for bankruptcy and emerged with two different subsidiaries conducting the predecessor company's ongoing business. Plaintiffs had brought a securities class action, which survived the bankruptcy as a claim against one of the subsidiaries.

Following the completion of the bankruptcy, many electronically stored documents were destroyed. The NTL court concluded that Defendant's duty to preserve began when litigation was foreseen by the former company, and ran to the successor Defendant, even though most of the relevant documents were last in the possession of the other, non-party subsidiary. It rejected Defendant's claim that it had no responsibility to preserve electronic documents of the parent company prior to the current suit. It also imposed a number of sanctions, including fees, costs and adverse jury instructions.

There is also a more dangerous spoliation bronco bucking at the back of the preservation corral. The hold duty is not limited to civil liability ramifications or even to anticipated civil lawsuits. Indeed, by virtue of Sections 802 and 1102 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, codified, respectively, at 18 U.S.C. § 1519 and 18 U.S.C. § 1512(c) http://uscode.house.gov/download/pls/18C73.txt, the duty cuts a much broader swath. These criminal evidence-tampering and obstruction-of-justice provisions impose substantial criminal penalties on any individual or entity – public or private – for destruction of evidence or obstruction of justice regarding any actual or "contemplated" federal investigation, matter or official proceeding.

When an acquiring company's counsel does its due diligence, it should thoroughly examine and assess the scope of regulatory power applicable to the pertinent industry and company, as well as the nature and extent of any actual lawsuits. However, in light of the common-law and SOX litigation-hold obligations, acquisition counsel must also focus on reasonably anticipated lawsuits and on federal governmental investigations, matters and proceedings.

There is scant case-law interpreting the reach of SOX sections 802 and 1102. However, each of the following situations would ostensibly warrant imposition of a SOX litigation-hold:

- commencement of an internal investigation of possible

violations of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, implying the

likely intervention of the Department of Justice;

- an employment discrimination accusation subject to Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission jurisdiction. (Compare the

civil setting, where two decisions have held that litigation

is reasonably anticipated once a (former) employee takes the

tangible step of filing an EEOC charge. Broccoli v.

EchoStar Commcn's, 229 F.R.D. 506 (D. Md. 2005)

http://Broccoli-Echostar-DMd-8-4-05.notlong.com

(LEXIS ID and password needed); Zubulake v. UBS Warburg

LLC, 220 F.R.D. 212 (S.D.N.Y. 2003) (Zubulake IV) http://www.nysd.uscourts.gov/courtweb/pdf/D02NYSC/03-08785.PDF.);

and

- the M&A deal itself – if contemplation of a

given corporate acquisition is, for example, likely to

trigger a Federal Trade Commission Hart-Scott-Rodino

review.

To prepare for the potential march of this parade of horribles, some practical takeaways for an acquirer are to try, wherever possible, to:

- ensure that the transaction agreement provides the

acquirer with ownership of all the target's pertinent

records, or if that is not possible (in the asset purchase

context, for example), then with electronic copies of, or

access to, those records

- obtain records in native electronic formats; and

- store obtained records in live/active format, rather than

placing them onto back-up media, which are susceptible to

corruption and are costly to restore.

III. Data-Roping By Counsel – Tying Up Loose Ends On The Retention And Storage Fronts

Transaction counsel face their own retention issues. In days past, if best practices were followed, pertinent written communications would have ended up in correspondence and diligence documentation hard-copy files for the deal; and important transaction documents all would have resided in closing volumes. Now, frequently deals are often negotiated through electronic exchange of draft documentation and communications on relevant deal points and diligence. Moreover, deals are concluded without a physical closing, meaning the parties no longer meet in a single location to execute the closing documents. Instead, executed copies are scanned to .pdf and emailed. Clients have additionally begun to opt out of having closing volumes printed. The written documents containing the negotiation history of the deal are now emails and multiple versions of word processing documents in the lawyers' firms' document management systems.

Numerous problems are posed by this decentralized storage, including great time and expense added to locating needed information, and risk of inadvertent destruction. For example, consider this potential scenario:

- An associate who worked on a deal leaves the firm.

- Upon departure or X days later, the firm follows its

usual procedure for departing employees and wipes the hard

drive of that associate's laptop and deletes his/her

entire E-mail box that had been stored on the central

server.

- Three months later, all back-up tapes that contained the

separated associate's e-mail messages have been

recycled and/or put back in the rotation (i.e., had

their contents overwritten).

- As to remaining lawyers and staff who may have worked on

the deal, the firm's centralized email server

continues to execute on its usual retention protocol, erasing

every 90 days.

All of a sudden, a lot of pertinent ESI is gone. A firm facing a public investigation or a malpractice claim following a deal gone sour may find itself in a very unenviable position. Ditto the firm that, even though not a target or party in such a proceeding or case, is viewed as a conduit/repository for an acquirer client. In a public investigation of, or derivative or class-action lawsuit against, the acquirer itself, the law firm would either receive a third-party subpoena or be expected to collect and produce client information it has stored.

Moreover, all of those concerns are not limited to "outhouse" lawyers. Especially in today's climate, where the federal government has very aggressively sough to puncture attorney-client privilege, general counsel should be proactive in seeking expansion of the scope and specificity of their companies' records retention/destruction policies and litigation-hold protocols.

As a consequence, law firms and law departments should adopt uniform storage, retention and deletion policies for the pertinent information. A "stop the presses" provision – providing a workflow to ensure that IT checks in with Firm Counsel and/or HR and/or the Records Department before overwriting data – should be in: a Records-Retention Policy (and in a separate Litigation-Hold Protocol, if any); and a Separation Policy/Checklist.

In general, there are competing philosophies and concerns regarding the respective dangers resulting from oversaving versus under-saving. There are risk-management, efficiency and cost issues emanating from saving everything indefinitely. However, as in the above hypothetical, gross under-saving is extremely problematic in its own right. Especially when much of the data is organized in a central repository extranet, for some time the data should be kept live – whether on the web server or on another computer – and backed up.

Conclusion: Riding Off Into The Sunset?

Electronic information management is not just for IT geeks or for litigators immersed in eDiscovery. Transaction counsel already take advantage of information management tools in rounding up client data for the deal. But both transaction counsel and client must be more mindful of their lasso and roping skills, or that data, once successfully wrangled, may slip the rope and kick.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.