This case summary includes an analysis of the 13th Chamber of the Council of State's reversal1 of Ankara Regional Administrative Court's judgment,2 which had dismissed the request to quash the Turkish Competition Board's (the "Board") decision3 regarding the allegations concerning resale price maintenance ("RPM") against Türk Henkel Kimya San. ve Tic. A.Ş. ("Henkel").

In its decision, the Board had concluded that Henkel had infringed Article 4 of Law No. 4054 on the Protection of Competition ("Law No. 4054") by determining the resale prices of its products and imposed an administrative fine of TRY 6,944,931.02. Under the judicial review that followed, the first instance administrative court and the appellant regional administrative court had both found the Board decision to be lawful. Nevertheless, the 13th Chamber of the Council of State decided that the Board has to prove with clear and tangible evidence, that the element of "coercion or incentive" by the supplier had reached a level that restricted the buyers` independent economic behaviour in terms of their freedom to set their own resale prices, and hence considerably raised the standard of proof for RPM cases. The ruling of the 13th Chamber of the Council of State is a signal to the Board to change its approach which has been getting stricter over the years in RPM cases.

i. Background

In the application filed with the Turkish Competition Authority ("TCA") on January 20, 2017, it was claimed that Henkel violated Law No. 4054 by determining the resale prices of its "beauty and personal care products" and "laundry and home care products." As a result of the preliminary investigation, it was decided to open a full-fledged investigation against Henkel with regard to the alleged RPM practices.

The Board noted that Henkel, with a computer program called "Field Control Services" ("FCS") could monitor the end-point sale prices for both its own and other firms` products. Additionally, Henkel`s field staff examine the product details such as promotional insert prices, the display conditions of Henkel products, etc. and upload the relevant photos to the FCS. Henkel also has another system called "Star Store" ("SS") for internal reporting its own products in the beauty and personal care categories, where it can monitor the product prices and check whether they were under or over the price recommended by Henkel. In this context, when a buyer's resale price was found to be lower than the recommended price, Henkel made various attempts to increase the price. Based on the case at hand, even though the rapporteurs were of the opinion that Henkel did not violate the law, the Board unanimously decided to impose an administrative fine of TRY 6,944,931.02 to the undertaking, on the ground that it had violated Article 4 of Law No. 4054 by way of indirectly determining the resale prices.

On September 9, 2018, Henkel applied for a judicial review and annulment of the Board's decision. In the first instance, Ankara 4th Administrative Court decided to dismiss the case as the subject matter of the case was found to be in accordance with the law. Henkel appealed the case to the Ankara Regional Administrative Court 8th Administrative Chamber where the court again rejected the application since the subject of the appeal was found to be in accordance with the legal procedure and substantive law, and Henkel`s allegations were not considered adequate for the judgment to be annulled. As a result, Henkel decided to take the matter to the Council of State, the highest court in the judicial review process.

ii. The Board's RPM Precedents Prior to the Ruling of the Council of State

When the TCA`s decisional practice since 1998 is examined, two things stand out. First, the Board's approaches on preliminary investigations and full-fledged investigations tend to differ, with regard to the distinction between restriction by object or effect. In its preliminary investigations the Board applies Article 9(3) of Law No. 4054, which is a tool used by the Board to terminate the preliminary investigation and refrain from initiating a full-fledged investigation on procedural efficiency grounds, among others, when the infringement affects only a small market, and in a way, conducts an effect analysis.4 However, in its full-fledged investigations, the Board predominantly considers RPM practices as restriction by object.5 In this approach, some actions have been deemed illegal on their own, regardless of the effects of such action. On the other hand, there have also been full-fledged investigations in which the Board conducted an economic analysis of the effects, such as the Tefal decision.6

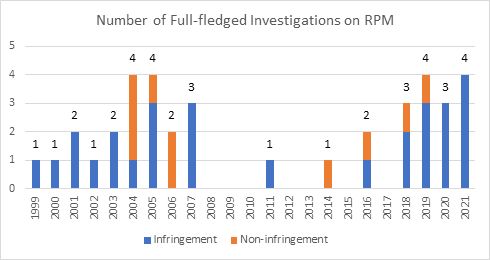

Secondly, when the Board's decisional practice is viewed chronologically, between years of 1998 and 2008, the TCA seems to have been relatively active regarding RPM allegations, by conducting 20 full-fledged investigations and imposing administrative fines in 14 of these cases. On the other hand, when we look at the 2008-2017 period, the TCA conducted only four full-fledged investigations and imposed administrative fines in only two of them, the Anadolu Elektronik and Aral Oyun cases.7 The reason for such noticeable decrease in the number of TCA's full-fledged investigations may be the Leegin Judgment8 of the U.S. Supreme Court in 2007, in which the century-old "per se" approach was abandoned and rule of reason analysis was adopted.

However, starting with the Henkel decision in 2018, the Board has imposed administrative fines in 12 full-fledged investigations out of 14 in total so far.9 Thus one can say that RPM activities have once again come under the TCA`s radar and close scrutiny. However, also in the period starting with 2018, in some of its preliminary investigations, the Board decided not to launch full-fledged investigations by applying Article 9(3) of the Law No. 4054.10

After examining recent decisions of the Board and the administrative fines it imposed, it is safe to say that TCA's enforcement activity on RPM practices has increased significantly and the Board have shifted into a stricter approach against RPM practices. Moreover, it seems like the increase in RPM cases will continue, as more full-fledged investigations are in the pipeline. Different periods in the Board's decisional practice and the gap between years of 2008-2017 can easily be noted by the below graph.

iii. The Council of State's Approach in the Henkel Case

Although the Council of State accepted that as a general rule, in a vertical relationship, Law No. 4054 prohibits suppliers from determining a minimum or fixed resale price for buyers, it held that Communique No. 2002/2 grants block exemptions to certain types of activities, albeit with certain types of limitations. Examples of these limitations are "impeding the buyer's freedom to set its own resale price" and "determining a minimum or fixed price as a result of coercion or incentive."

The Council of State held that Henkel sells and distributes its products through large-scale retailers and distributors, and there are no explicit provisions regarding RPM under the agreements concluded with them. Therefore, the allegation concerns whether Henkel determined the resale prices indirectly, although in terms of determining if it is anticompetitive behaviour causing an infringement, there is no difference between direct or indirect implementation of RPM practices. Accordingly, it is important to establish in this case whether Henkel, by using the monitoring systems (FCS and SS), had tried to determine fixed resale prices through its price recommendations by using coercion or incentives.

Examining the evidence presented during the full-fledged investigation, it is noted that the phrase "taking action" is used multiple times in the intercompany correspondences. However, when statements from Henkel's buyers are reviewed, buyers insist that recommendations of Henkel and/or phrases like "taking action" are merely recommendations and do not obstruct the buyer's freedom to determine the resale price in practice. As previously stated, even if a supplier`s conduct can seem coercive or based on incentives, in order to fulfil the element of "coercion or incentive" stated in the Communique No. 2002/2 and Guidelines, the "coercion or incentive" in question must be at such a level that would affect the buyers' independent economic behaviour in terms of their freedom to determine resale prices. Otherwise, in a situation where the buyer can make independent decisions, it is not possible to state the supplier is determining the resale price or even engaging in anti-competitive behaviour. In line with the above-mentioned elements and criteria, the Council of State found that Henkel`s conduct did not constitute an anti-competitive act of coercion or incentive, but was merely a reproach towards the resellers who did not comply with recommended prices.

Even though the Board stated in its decision that the resale prices showed increase following Henkel's objections to the resellers, Council of State found that it is not clear whether the price adjustments in question were made as a result of coercions or incentives by Henkel's employees. The Court also noted that since Henkel has strong competitors in the market and does not have more than 20-25% market share, there is a strong substitution effect between the competitors in relevant market, and consumers' preferences are likely to be quickly affected by any price adjustments. Furthermore, since the large-scale retailers are powerful and there are no exclusivity conditions for distributors, it is highly unlikely that Henkel will be able to determine the resale prices. In other words, even if the prices have increased, the Court required that a strong link between Henkel's actions and the price adjustment must be established based on clear and tangible evidence, hence the bar for the standard of proof has been raised.

iv. Conclusion

As a result, the 13th Chamber of Council of State decided Henkel did not violate Article 4 of the Law No. 4054 by determining resale prices and found the Board's decision unlawful. The decision can be interpreted as the Council of State stepping away from restriction by object for two reasons:

- The "coercion or incentive" in question must be at such a level that it would affect the buyers' independent economic behaviour in terms of their freedom to determine resale prices, and

- The price adjustments in question must be shown to be made clearly as a result of the supplier`s (Henkel's) conduct.

For now, it seems that the Council of State is trying to steer the TCA's considerably more stringent approach towards a more effects-based approach and restrain the TCA from penalizing those RPM practices with no negative effect on the market. The ruling of the 13th Chamber of the Council of State considerably raised the standard of proof for RPM cases and this may cause the Board to change its strict approach in the forthcoming days.

Footnotes

1. The 13th Chamber of Council of State's judgment dated July 6, 2021, and numbered 2021/969 E., 2021/2654 K.

2. Ankara Regional Administrative Court 8th Administrative Chamber's judgment dated December 23, 2020, and numbered 2020/394 E., 2020/2451 K. Following the above judgment of the Council of State, the case was returned to the Ankara Regional Administrative Court. The 8th Chamber of Ankara Regional Administrative Court with its judgment dated 09.09.2021 and numbered 2021/1300 E., 2021/1241 K., rescinded the first instance Ankara 4th Administrative Court's decision dated 08.01.2020 and numbered 2019 E., 2020/50 K. and thereby quashed the Board's Henkel decision.

3. The Board's Henkel decision August 19, 2018, 18-33/556-274.

4. The Board's Dagi decision dated July 15, 2009, 09-33/725-165, KWS decision dated November 25, 2009,09-57/1365-357 and Yatsan decision dated September 23, 2011, 10-60/1251-469, Aygaz decision dated March 3, 2013, 13-14/204-105; Çağdaş/Zuhal Müzik decision dated October 24, 2013, 13-59/825-350; Duru Bulgur decision dated March 8, 2018, 18-07/112-59 ; Yataş decision dated February 6, 2020, 20-08/83-50 .

5. Such as, the Board's Anadolu Elektronik decision dated June 23, 2011, 11-39/838-262 ; Henkel decision dated August 19, 2018, 18-33/556-274 ; Sony Eurasia decision dated November 28, 2018, 18-44/703-345 ; Maysan Mando decision dated June 20, 2019, 19-22/353-159 .

6. The Board's Tefal decision dated March 4, 2021, 21-11/154-63 .

7. The Board's Anadolu Elektronik decision dated June 23, 2011, 11-39/838-262, Aral Oyun decision dated October 7, 2016, 16-37/628-279.

8. Leegin Creative Leather Products, Inc. v. PSKS, Inc., 551 U.S. 877 (2007)

9. The Board's Henkel decision dated August 19, 2018, 18-33/556-274 ; Sony Eurasia decision dated November 28, 2018 , 18-44/703-345 ; Turkcell decision dated January 10, 2019, 19-03/23-10 ; 3M decision dated April 18, 2019, 19-22/232-13 ; Maysan Mando decision dated June 20, 2019, 19-22/353-159 ; Tefal decision dated March 4, 2021, 21-11/154-63 ; Akaryakıt decision dated March 3, 2020, 20-14/192-98 ; Bellona decision dated March 26, 2020, 20-16/231-112 ; Baymak dated March 26, 2020, 20-16/232-113 ; DYO decision dated April 15, 2021, 21-22/267-117 ; Anka Mobil decision dated April 15, 2021, 21-22/266-116 ; Philips decision dated August 05, 2021, 21-37/524-258 .

10. The Board's Yataş decision dated February 6, 2020, 20-08/83-50.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.