Introduction

The job of a court when interpreting a written contract, including a lease, is to work out what the document means, not what either party thinks it means. This is known as the objective theory of contract interpretation. Specifically, it is the meaning that the document would convey to a reasonable person having all the background knowledge that would have been reasonably available to both parties in the situation in which they were at the time of the contract. This includes knowledge to be gained from the whole document and also such other background knowledge as the reasonable person would consider relevant.

A party may apply to the court to rectify a document because it does not reflect the terms the parties actually agreed, or because the document does not reflect the terms one party thought had been agreed, in circumstances where the other party should not be permitted to take advantage of the mistake. Rectification of a document on either of these grounds is beyond the scope of this update.

What happens, however, if the court is satisfied that something has gone wrong with the language? This is difficult to establish because a court does not easily accept that people have made linguistic mistakes, particularly in formal documents. Occasionally though, the court is satisfied that a mistake has been made. This was the case in the recent decision of the UK Court of Appeal in MonSolar IQ Ltd v Woden Park Ltd [2021] EWCA Civ 961. That case concerned the drafting of a rent-review clause in a lease.

The Court of Appeal decision

The lease provided for annual rent reviews based on movements in the Retail Price Index (RPI). (This can be compared to the Consumer Price Index published by the Statistics Office of the Government of the Cayman Islands.) Typically, the idea of such rent reviews is for the annual rent to keep pace with increases in inflation (although sometimes it may mean the annual rent is decreased because of deflation).

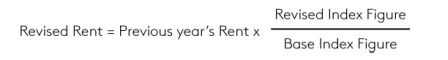

In this case, the rent-adjustment mechanism was reduced to a formula which, effectively, read as follows:

(This is a simplified version of the actual formula.)

The problem with this formula was that the "Base Index Figure" remained the same throughout the life of the lease. Unless corrected, this had the effect of producing cumulative, compounding increases in the annual rent. In other words, assuming the usual upward increases in inflation, the strict application of the formula would lead to cascading increases in the annual rent. The trial judge, Fancourt J, at para 9 of his judgment, gave this example of the formula's effect:

"Assuming RPI increases of 5% in each of the first three years of the term, the rent of £15,000 would thereby increase to £15,750 at the end of year one; to £17,325 (ie £15,750 + 10%) at the end of year two; and to £19,923.75 (ie £17,325 + 15%) at the end of year three. Thus, increases in rent upon the sequential annual rent reviews are not merely compounded, in the sense that it is the current, previously increased rent that is further increased on each Review Date; the current rent is also increased once more by the same factor by which the rent was previously increased, not just by a new factor reflecting the subsequent increase in the RPI index."

At first instance, Fancourt J held that, read literally, the formula was irrational and arbitrary. He was satisfied, therefore, that something had gone wrong with the drafting, ie, there was a mistake. Importantly, he also concluded that it was clear how the mistake should be corrected.

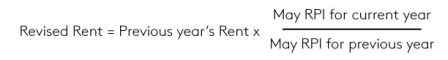

The Court of Appeal (Nugee LJ, with whom Males and Baker L JJ agreed) agreed with Fancourt J that the formula should have read as follows:

Given the lease as a whole, the Court of Appeal agreed that the formula contained a drafting error and it was clear how it should be corrected.

Comments

This remedy should not be seen as a "get out of jail card" for sloppy drafting, as the parties will usually be held to the actual language they have used. In rare cases, however, to paraphrase the words of Lord Hoffmann in Chartbrook Ltd v Persimmon Homes Ltd [2009] 1 AC 1011, at para 25, it will be clear that something has gone wrong with the language and that it is clear "what a reasonable person would have understood the parties to have meant".

It is the second condition that will usually be the most difficult to establish. Therefore, when using a formula, the drafter should consider including worked examples as aids to interpretation.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.