ABSTRACT

In the Netherlands, the Dutch Withholding Tax Act has been introduced since 1 January 2021. Before implementation there has been critique on this Tax act because of the unproportional taxation that can occur in certain situations. Together with the legal uncertainty that is bound to the concept of the control group this brings new challenges and bottlenecks to the Dutch Withholding Tax Act along the current legislation of Hybrid Mismatches in the Dutch Corporate Income Tax Act as a result of the implementation of ATAD2. This issue is especially important for private equity investors who invest in companies together.

Key Words: Hybrid Mismatch, Withholding Tax Act, Bottleneck, Control Group, Private Equity, Double Taxation,

INTRODUCTION

With the implementation of the Dutch Withholding Tax Act ("WHTA") on 1 January 2021 and the regulation on hybrid mismatches in regard to ATAD2 in the Dutch corporate income tax act ("CITA"), there is legal uncertainty on the concept of the 'control group' ("CG"). The concept of CG is i.a. important for private equity investors who invest together through a partnership, and possibly also for Turkish investors who for example would like to invest via the Netherlands through a legal person like a BV or by immigrating to The Netherlands themselves and investing as an individual.

For Dutch tax purposes, partnerships (CV-like entities) are seen as non-transparent from a unique Dutch tax perspective while in other member states they are seen as transparent. This means that the same entity that is not seen as a legal person in another country, is seen as such in the Netherlands, as a result of which the taxation falls on that legal person instead of on the underlying shareholders. In the other country the tax would be levied on the underlying shareholders.

This difference in qualification is the base for the risk of a hybrid mismatch with respect to the concept of CG. However, this concept is also important for the WHTA to determine whether there is a taxable person. In this paper I will explain by means of an example when there may be a CG for the WHTA and the CITA.

Section 1 sets out the WHTA, Section 2 sets out the hybrid mismatch, Section 3 sets out the qualification of a CG. Section 4 sets out the bottleneck that arises between the hybrid mismatch and the WHTA due to the concept of CG.

I. DUTCH WITHHOLDING TAX ACT

From 1 January 2021 the WHTA has been implemented; WHT will be levied on intra-group interest payments and royalties paid or accrued by a Dutch corporate taxpayer (an entity or a permanent establishment ("PE")) to a related entity that is a resident in:

- A jurisdiction with a statutory tax rate lower than 10%

- A jurisdiction that is included on the European Union ("EU") list of non-cooperative jurisdictions

- Other jurisdictions if the entity allocates the interest or royalties to a PE in a jurisdiction with a statutory tax rate lower than 10% or a jurisdiction that is included on the EU list of non-cooperative jurisdictions.

- Certain abusive situations, which includes (deemed) payments/accruals to hybrid entities.

The withholding tax rate is equal to the highest rate of CIT. In 2021 it will be 25%. The WHT is levied on the Dutch corporate taxpayer.

II. HYBRID MISMATCHES (ATAD2)

ATAD2 aims to counter hybrid mismatches. Hybrid mismatches are situations in which a tax benefit is obtained between related entities in EU member states and between EU Member States and third countries. These benefits are obtained due to qualification differences of entities.

These differences occur in situations in which a tax benefit is obtained by making use of differences between different tax systems with regards to the fiscal treatment of entities, instruments or permanent establishments. The differences between these corporate tax systems can result in the following:

- A payment (in one country) is deductible, but the corresponding revenue (in the other country) is not taxed (deduction – no inclusion), or

- One and the same payment (cost or loss) is deductible multiple times (double deduction).

In the first case the mismatch is neutralized by applying the 'primary rule'1; no deduction of a payment of interest at the level of the sending entity that at the receiving entity is not included in the tax base (deduction, no inclusion), this is the case if the sending party is located in the EU. When the sending party is not located in the EU, the secondary rule2 is applicable in which the payment in most cases will be included in the tax base of the receiver.

If there is a situation under ii. the tax benefit that can be obtained with double deduction is removed by refusing the deduction once. This primary rule allows deduction in the country that is considered to be the country of the payer. However, if the other country also allows the deduction, a secondary rule stipulates that the country of the payer still refuses the deduction of the payment.

III. QUALIFICATION OF PARTNERSHIPS; CONTROL GROUP

For the definition of a CG (and therefore a related entity) article 12ac paragraph 2 CITA refers to article 10a paragraph 6 CITA in which the CG is mentioned but not defined, in addition the CG must hold 1/3 of the shares in the entity to be an associated enterprise. Please note than on an EU level according to article 2 of ATAD2 this share must be 25%. Notice that the interpretation of Dutch CITA is less stringent then on EU level. This leaves room for a lot of interpretation and can cause legal uncertainty.

The Dutch legislator is aware of the legal uncertainty that the lack of a definition brings, also in regard to the uncertainty it will bring to the WHTA. But the legislator has chosen for a case-by-case approach3. According to the legislator whether there is CG is depended on the case-by-case facts and circumstances and in the opinion of the Dutch government it is preferable not to define the concept of CG. To depend on whether there is a CG I have chosen to take the approach as stated by the authors in the WFR article 2020/2374 . According to the criteria as set out in the article a CG is considered to be present if the following 2 elements are present:

- A coordinating (legal) person has the material control over the forming of the investment; and

- Each shareholder provides equity and (risky) loans on more or less similar terms and conditions.

These main elements originate from ATAD1 in article 2 for the definition of an associated enterprise in which is stated that an associated enterprise is 'a person who acts together with another person in respect of the voting rights or capital ownership (....)'.

The lack of the definition of a CG stems from the fact that the concept of associated enterprise (ATAD2) did not include an explanation of when it refers to acting together. When looking for a definition of acting together looking at it from an international perspective on BEPS level, is the best approach.

In the 2015 report of BEPS5, the OECD states that acting together is when two (legal) persons will be treated as acting together in respect of ownership or control of any voting rights or equity interest if;

- They are member of the same family

- One person regularly acts in accordance with the wishes of the other person

- They have entered into an arrangement that has material impact on the value or control of any such rights or interest; or

- The ownership or control of any such rights or interest are managed by the same persons or group of persons

Another underlying basis for these 2 main elements is the term Effective control; One person has a sufficient interest in another person and as a result has de facto control over decisions. When there is enough effective control depends on the facts and circumstances and should be assessed in a case-by-case approach6. There can also be effective control when one entity has 20% of the shares and all the others only have small shares7.

The above stated can give a sufficient guideline on when it is possible to qualify a group of investors as a CG for CITA purposes.

BOTTLENECK HYBRIDE MISMATCH AND WHTA

In both Dutch tax codes the problem that causes taxation is the definition of a CG. This problem arises due to the look-through approach8 that is implemented in both tax codes in which for the Dutch fiscal analyses, you have to look at what the tax implications would be if an entity would have been established in The Netherlands. This causes bottlenecks between the two tax codes. These bottlenecks are caused by the unique Dutch fiscal qualification of some CV-like entities, qualifying it as non-transparent, whereas other countries tend to qualify a CV-like entity as transparent.

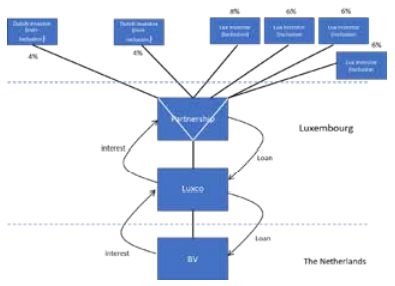

The definition of a CG is defined in article 12ac paragraph 2 CITA and article 1.2 WHTA. In the following I will discuss a structure in which I will argue why there is a CG. In the following the BV can deduct interest from its tax base without the Dutch investor at the top of the structure including the income in its tax base due to the hybrid character of the partnership, when the partnership can be qualified as a CG the BV would not be able to deduct the interest in the CITA that is attributed to the Dutch investors. The example below explains this further.

Example

In the above example the partnership receives a loan from Lux and Dutch investors. The partnership is located in Luxemburg alongside the Luxco. The partnership grants the same loan to Luxco and Luxco grants the loan to BV in The Netherlands. Subsequently BV pays interest on the loan to Luxco, Luxco pays the same interest further to the partnership. HYBRID MISMATCH The partnership is a hybrid entity, For Dutch purposes it is treated as a non-transparent entity, meaning that the interest income is included as income on the partnership level. For Luxemburg purposes the partnership is treated as a transparent entity, meaning that the interest is included on the level of the Lux investors and the Dutch investors. Luxco to Cg With this difference in qualification you can see that there is an inclusion in the tax base of the Lux investors. But due to the hybrid character of the partnership, the interest income is not included in the tax base of the Dutch investors but in the tax base of the partnership for Dutch tax reasons. This results in that there is possible deduction – non – inclusion for the interest that can be attributed to the Dutch investors according to article 12aa paragraph 1 under b CITA. But to qualify this transaction as a hybrid mismatch according to Dutch CITA, the Dutch investors and Luxco have to be qualified as related entities according to the definition of related entities for CG´s as stated in article 12ac paragraph 2 CITA. As stated in section 3, there are some conditions that must be met in order for there to be a CG according to the Dutch legislature;

- A coordinating (legal) person (one of the investors) has the material (effective) control over the - forming of the investment; and

- Each shareholder provides equity and (risky) loans on more or less similar terms and conditions (acting together).

If both of the above conditions are met it would be "more likely than not" that in the example the partnership will be qualified as a CG for Dutch CITA purposes and thus resulting in that the partnership and Luxco are associated enterprises. That will result in that the interest that BV pays to Luxco - at least for the part that belongs to the Dutch investors - will not be deductible as a result of it being a hybrid mismatch. This is the rectification that ensues when qualified as a hybrid mismatch. And that the interest that is in the tax base of the partnership will be included in the tax base of the Dutch investors. This is also a very interesting point for Turkish investors that have a presence in The Netherlands via a BV or are living in The Netherlands and invest as an individual. In that case it is in the best interest that the hybrid character of the partnership as stipulated in the example remains without the partnership becoming an associated enterprise for Dutch tax reasons and therefore becoming a hybrid mismatch. This ensures that the interest income stays in the tax base of the partnership and not to the underlying `Dutch investors`.

A potential example in which the investors are deemed to 'act together' is if one of the Dutch investors makes the decision on what the rest of the group will invest in, thus giving the Dutch investor the control over the shares of the rest of the investors. If it shows in practice that this is the case, it would be more likely than not that the investors could be qualified as a control CG and therefore form an associated enterprise to Luxco.

WHTA

At first glance it wouldn´t seem that the WHTA would be applicable in the example and that BV would not have WHTA levied on the interest it pays to Luxco. Luxembourg is not a country that is blacklisted by The Netherlands. But because of article 2.1 paragraph 1 sub c WHTA Luxco could be a taxable person if Luxco does not have substance according to Dutch guidelines, a lack of substance indicates an artificial constructure. Substance is in this case part of the objective test. With this the Subjective test also has to be tested; what are the tax implications if the partnership directly lends the loan to BV instead of Luxco first?

As described above, the partnership is a hybrid entity: non-transparent according to Dutch tax standards, transparent according to Luxembourg tax standards. In this case, the partnership is in principle fully taxable on the basis of Art. 2.1 paragraph 1 part e of the WHTA, unless the conditions of the look-through approach of Art. 2.1 paragraph 4 of the WHTA are met. This requires that each investor in the partnership:

- Holds a qualifying interest,

- Does not qualify as a taxpayer for the WHTA and

- Qualifies as a beneficiary of the interest in their country of residence.

The significance of a control CG is of importance for the condition of "Holds a qualifying interest". The same criteria that is of importance for hybrid mismatch in regards to the CG is also of importance for the WHTA (bottleneck). The partnership can be considered a CG under the circumstances beforementioned in Section 3. If the partnership is considered to be a CG it would mean it has a qualified interest in Luxco and ergo is an associated enterprise in accordance with article 1.2 paragraph 1 sub c under 5 WHTA.

The third condition of art. 2.1 paragraph 4 WHTA is where the discussion would occur with the Tax authority, because the Dutch investors are in this case not the beneficiary of the interest. This is a result of the non-transparency of the partnership for Dutch tax purposes and that the Dutch investors don't take the interest income into account for tax purposes. If in this case it could be argued that the investors could be qualified as a CG and they would hold a qualifying interest, it would be likely that the Tax Authority would state that the third condition should also be met.

CONCLUSION

If the partnership was deemed to be a CG for CITA and WHTA purposes then for the CITA the interest income that the partnership receives will be included in the tax base of the Dutch investors and the BV will be restricted to deduct the interest that can be attributed to the Dutch investors.

For WHTA purposes the BV would have Withholding tax levied on the interest paid to Luxco. This would result in a double taxation; namely in the CITA due to a hybrid mismatch and in the WHTA all due to the (lack of a) definition of a CG.

The above stipulates the importance of a clear definition or at least clear guidelines on when for Dutch tax reasons there is a CG present. This can make the difference between double taxation or no taxation at all in the CITA and the WHTA. Thus, when there is a CG will have to be apparent from the facts and circumstances, but for now the Dutch legislator prefers the case-by-case approach. For the future, concrete cases will have to show when there can be a CG for Dutch tax purposes and in what kind of cases. In conclusion The Netherlands is still very much an appealing place to settle as a (legal) person, but like always you have to be cautious of the rules and regulations in place.

Footnotes

1. Article 12aa CITA

2. Article 12ab CITA

3. Kamerstukken II 2016/17, 34552, nr. 3, p. 30.

4. van der Have BSc, J. C., & van Hulten MSc, L. C. (2020). De samenwerkende groep in de context van hybride mismatches. WFR, 2020(237), 1613–1619.

5. Neutralizing the effects of hybrid mismatches arrangements OECD 2015

6. van der Have BSc1, J. C., & van Hulten, L. C. (2020). De samenwerkende groep in de context van hybride mismatches. Weekblad Fiscaal Recht, 2020(237), paragraph 2.2

7. Example 11.3 uit OESD (2015), Neutralising the Effects of Hybrid Mismatch Arrangements, Action 2 — 2015 Final Report, p. 449-450.

8. Treating Luxco as if it is a Dutch BV according to article 12 ad CITA; imported mismatch

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.