In recent years, Singapore Courts have had a number of opportunities to consider the scope and applicability of the fraud exception, which has been invoked by banks to resist payment under letters of credit. However, is it possible to resist payment in circumstances where the fraud exception has not been established, but where the beneficiary has breached warranties provided to the issuing bank?

In the recent decision of Crédit Agricole Corporate & Investment Bank v PPT Energy Trading Co Ltd [2023] SGCA(I) 7 ("CACIB v PPT"), the Singapore Court of Appeal ("SGCA") answered this question in the affirmative. The SGCA allowed the appeal by Crédit Agricole Corporate & Investment Bank ("CACIB") on the narrow ground that PPT Energy Trading Co Ltd ("PPT") had breached its warranty under the letter of indemnity that it had marketable title at the time title passed.

This article follows from our earlier article on the Singapore International Commercial Court's decision in Crédit Agricole Corporate & Investment Bank v PPT Energy Trading Co Ltd [2022] SGHC(I) 1, which can be accessed here: Defences to Payment in Letter of Credit Transactions

Background

CACIB v PPT involved a dispute between (i) CACIB, the issuing bank of a letter of credit ("LC") issued pursuant to an application by Zenrock Commodities Trading Ltd ("Zenrock"), and (ii) PPT, the beneficiary under the LC. On its face, the LC issued by CACIB appeared to be for the financing of Zenrock's purchase of cargo from PPT.

As part of the financing arrangements between CACIB and Zenrock, CACIB was (i) granted a floating charge on all goods financed by CACIB; and (ii) assigned the receivables which were due from the on-sale of the cargo from Zenrock to Total Oil Trading SA ("TOTSA").

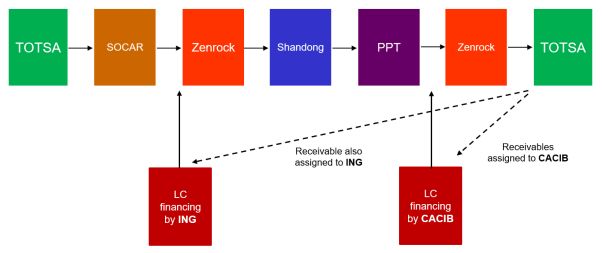

In reality, however, the situation was more complex and involved multiple round tripping transactions, as depicted in the diagram below:

The wider trading background revealed that Zenrock's first purchase of the cargo was from SOCAR Trading SA, and that this purchase was financed by ING Bank NV ("ING"). Crucially, Zenrock had fraudulently (i) granted a floating charge over the goods, and (ii) assigned receivables due from TOTSA, twice over, i.e. to both CACIB and ING. It also transpired that Zenrock had presented to CACIB a fabricated sales contract which falsely represented the sale price to be higher than the actual contract.

Zenrock's fraud came to light when TOTSA highlighted to CACIB and ING that it had received competing notices of assignment in relation to the proceeds the sale contract between Zenrock and TOTSA.

In the proceedings before the Singapore International Commercial Court, the Honourable International Judge Jeremy Lionel Cooke ("Cooke IJ") dismissed CACIB's claims, finding that CACIB was not entitled to refuse payment under the LC because (i) PPT had not acted fraudulently; and (ii) in the absence of payment due under the LC by the due date, CACIB could not rely on the warranties and/or indemnities in the letter of indemnity.

CACIB's appeal to the SGCA

There were two main issues before the SGCA:

- First, whether CACIB was entitled to rely on Zenrock's undoubted fraud to set aside and avoid liability to pay under the letter of credit it issued in favour of PPT.

- Second, in relation to the letter of indemnity presented by PPT, whether the letter of indemnity was effective, and whether there was a breach of warranty.

On the first issue, the SGCA found that CACIB was not entitled to rely on Zenrock's fraud to avoid liability under the LC. In reaching this finding, the SGCA reiterated the trite position that the only narrow exception to the autonomy principle is the fraud exception, i.e. "where the seller, for the purpose of drawing on the credit, fraudulently presents to the confirming bank documents that contain, expressly or by implication, material representations of fact that to his knowledge are untrue". The SGCA also observed that if CACIB were allowed to avoid liability by relying on Zenrock's fraud, such a finding would significantly undermine the whole system of documentary credits.

On the second issue, the SGCA overturned the findings of Cooke IJ and held that the letter of indemnity was effective from the moment it was issued and CACIB could rely on the warranties therein even though it had not made payment by the due date. The words, "In consideration of your making payment ... at the due date ... we hereby expressly warrant ..." did not make payment at the due date necessary before the warranties became effective. Having made this decision, the Court found that PPT had breached the warranty that it had "marketable title". The Court based its findings on the following:

- The title obtained by PPT was of uncertain value in circumstances where (i) inconsistent charges had been granted over the same goods, and (ii) the floating charges had crystallised before title had allegedly passed to PPT. That PPT had no knowledge of the inconsistent charges was immaterial because it was not a bona fide purchaser for value at the time title supposedly passed to PPT.

- While PPT may have been acquitted of actual complicity in Zenrock's fraud, it was not a bona fide purchaser – PPT's witnesses had attempted to conceal knowledge of the round-tripping from the Court, and were, on the whole, not credible. There were therefore well-founded concerns about the marketability of the title held by PPT.

In the circumstances, the Court held that PPT did not have marketable title free of hazard or litigation.

Significance

This is a rare case in which a bank has successfully resisted payment under a letter of credit despite failing to establish the fraud exception. Insofar as the beneficiary's intent was concerned, it was sufficient that the beneficiary was not a "bona fide" purchaser; the bank did not need to establish fraudulent intent.

It bears emphasis that the Court's decision was highly specific to the facts of this particular case. Among other things, PPT had warranted, rather than merely represented, that it had marketable title. The Court's findings were also based on the specific mechanics of Zenrock's fraud, where the floating charge had been granted to ING and crystallised before PPT allegedly received title; the charge therefore rendered uncertain the value of subsequent title, including the title allegedly obtained by PPT.

Nevertheless, the Court's decision sends a clear message that beneficiaries cannot demand payment on letters of credit where they have made false warranties and have not acted in good faith.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.