INTRODUCTION

This article explains the U.S. and Indian tax considerations that apply to the sale of shares of an Indian company by an individual who is a U.S. Person holding the shares for investment purposes. It provides a holistic analysis for U.S. Persons investing in shares of an Indian company. The important takeaway is that while tax rules generally appear to be similar in India and the U.S., several different provisions in the domestic law of each country produce adverse consequences for those who are not well-advised.

Notably, both jurisdictions take into account the residency status of the seller and the source of the gain from the sale of shares of stock to determine taxation rights. As an experienced global investor may anticipate, while the principles appear to be the same, the results are very different.

RESIDENCY STATUS OF THE SELLER

U.S. – A U.S. Person Is Subject to Tax on Worldwide Income

The U.S. taxes individuals who meet the definition of a "U.S. Person" on a worldwide basis. An individual is treated as a U.S. Person1 if the individual is a U.S. citizen or a U.S. resident. A U.S. resident includes a lawful permanent resident ("Green Card Holder") and an individual who meets the "Substantial Presence Test"2 in the year for which residence is at issue.

For an individual who is a U.S. Person because of citizenship or the issuance of a Green Card, gain from the sale of shares in an Indian company will be subject to U.S. tax regardless of physical residence.

India – A Non-resident Is Taxed on Indian-Source Income

Indian tax law follows residence-based taxation for Indian tax residents and source-based taxation for non-residents. Income of a non-resident is sourced in India only if the income is received, or deemed to be received, in India or it accrues or arises, or is deemed to accrue or arise, in India.3 "Income deemed to accrue or arise in India" has been defined to include income derived by a non-resident from the transfer of a "capital asset" situated in India. "Capital asset" means property of any kind held by a taxpayer, and hence, shares of an Indian company are regarded as a capital asset situated in India unless the taxpayer is a dealer in securities and the shares are treated as the equivalent of inventory. Therefore, any income derived by a non-resident from the transfer of shares of an Indian company is deemed to accrue or arise in India and, hence, is subject to capital gains tax in India.

Conflict of Laws

Because the capital gain is taxed in the U.S. under concepts of residence-based taxation and, at the same time, the gain is taxed in India under concepts of source-based taxation, each country claims the right to impose tax on the capital gain derived from the sale of the stock of an Indian company by a U.S. Person.

SOURCE OF THE GAIN AFFECTS FOREIGN TAX CREDIT RELIEF

In order to avoid double taxation, U.S. domestic tax law allows a taxpayer to claim a foreign tax credit to reduce the U.S. tax due on the same stream of foreign-source income.4 Domestic law is augmented by the terms of the India-U.S. Income Tax Treaty (the "Treaty").5

Briefly, U.S. tax law allows taxpayers to claim the benefit of the foreign tax credit to reduce the U.S. tax liability on the same gain only if both of the following conditions are satisfied:

- The income is considered to be foreign-source income under the provisions of U.S. tax law.6

- The foreign tax is an income tax in the U.S. sense.7

Therefore, U.S. tax law requires another layer of analysis to ascertain whether the Indian income taxes paid on the capital gain on the sale of the stock of an Indian company can reduce the U.S. tax liability on the capital gain.

Source of the Gain Depends on the Residence of the Seller

The source of the gain controls how much of the U.S. tax can be reduced by the foreign tax credit. If none of the gain is deemed to be foreign-source income, no portion of the U.S. tax on that gain can be reduced by a credit for Indian tax in the year of the sale. Of course, if the U.S. taxpayer reports other items of foreign income that fall in the passive basket or the high-tax basket, as the case may be, the Indian tax paid on the sale of the stock of the Indian company can be used to reduce the U.S. tax on that other foreign income.

The U.S. follows the common law principle of mobilia sequuntur personam in determining its right to tax the capital gain arising from the sale of a personal property. The Latin phrase "mobilia sequuntur personam" literally means "movable things follow the person". In other words, it holds the situs of a property to be the domicile of the owner.

Code §865 incorporates the general theme of mobilia sequuntur personam and provides that the taxation of the gain on the sale of a personal property depends on the residence of the seller. Any gain from the sale of a personal property by a U.S. resident is a U.S.-source income and is therefore subject to U.S. Federal income tax.8 On the other hand, any gain from the sale of a personal property by a U.S. non-resident is a foreign-source income.9 In other words, the source of the gain is in the taxpayer's country of residence. The place of sale, place of execution, place of the taxpayer's activities with respect to the property, and location of the property are irrelevant.

Special Definition of "U.S. Resident" for Foreign Tax Credit Purposes

The definition of the term "U.S. resident" under general U.S. tax principles, discussed above, is adjusted when determining the source of income under Code §865. An individual is a U.S. resident for foreign tax credit purposes in any of the following circumstances:10

- Any individual who is a U.S. citizen or a resident alien (i.e., a Green Card Holder or an individual who meets the Substantial Presence Test) who does not have a "tax home"11 in a foreign country

- A non-resident, non-citizen individual who has a tax home in the U.S.

Subject to one major exception, all other individuals are non-residents under Code §865.

The exception is relatively straightforward. No person can be considered to be a non-resident with respect to a particular sale of property unless that individual actually pays a foreign income tax of at least 10% of the gain12 on the sale in question.13 Since (i) the tax rate in India on the capital gain from a sale of corporate stock is 10% or more under all circumstances and (ii) no special set-offs, such as increases to basis to offset reduce the effect of inflation, are allowed, this issue is not discussed further.

Thus, two types of individuals are non-residents for foreign tax credit purposes:14

- A non-resident alien individual (i.e., an individual who is not a U.S. citizen, Green Card Holder, nor non-citizen individual who is a resident under the Substantial Presence Test) who does not maintain a tax home in the U.S.

- A U.S. citizen or resident for tax purposes who maintains a tax home in a foreign country or a U.S. possession and pays a foreign income tax of at least 10% on the gain in question

Because the definition of a U.S. resident is qualified by the requirement that the individual must not have a tax home outside the U.S., if a U.S. citizen or Green Card Holder has been living in India for a considerable period of time with a permanent business or employment located in India, the individual should not fall within the definition of a U.S. resident for foreign tax credit purposes. Consequently, the gain from the sale will be treated as a foreign-source income.

Example 1: A Green Card Holder with a Tax Home in India

Mr. X, an Indian citizen, arrives in the U.S. in the 1980's and obtains a Green Card. He returns to India in 1990, when he is offered a lucrative full-time job from an Indian employer. He retains his Green Card after departing the U.S. Through 2019, he invests in shares of several Indian companies. He sells the stock at a substantial gain in 2019 and is subject to Indian tax at the rate of 10%. That tax is fully paid.

Residence for Foreign Tax Credit Purposes: Code §865

Mr. X is a U.S. Green Card Holder (i.e., a lawful permanent resident). However, his principal place of employment is in India in 2019, the year in which the gain is recognized. Therefore, it appears that he does not have a tax home in the U.S. Also, the tax liability in India is equal to or more than 10% (20% in this example). Consequently, he is treated as a U.S. non-resident for Code §865 purposes. The gain will be treated as foreign-source income.

Residence for Purposes Other than Foreign Tax Credit: Code §7701(b)(30)

Merely because Mr. X is a U.S. non-resident for purposes of Code §865 does not mean that he is a non-resident for other purposes of the Code. In the absence of a treaty election to be treated solely as a resident of India under the Treaty's dual-resident tiebreaker provision,15 Mr. X will continue to be treated as a U.S. resident under Code §7701(a)(30). Consequently, he is a U.S. Person and is taxed on his worldwide income, including gains from sales of stock of Indian companies.

The foregoing example indicates that the relevance of Code §865 is to ascertain the source of the gain to determine whether a portion of Mr. X's U.S. tax liability is attributable to net foreign-source income. In the facts presented, Mr. X's tax return will report foreign-source gain. Within the limitations of Form 1116, the Indian tax should be available to reduce taxable income.

The above is an example of a perfect fact pattern that allows Mr. X to benefit from the credit. That would not be so if Mr. X were a resident of the U.S. under Code §865(g)(2), as discussed below.

Example 2: A Green Card Holder with a Tax Home in the U.S.

Mr. Z, an Indian citizen, arrives in the U.S. in the 1980's and obtains a Green Card. He remains in the U.S. with his family where he runs a successful business. Over the years, he invests in shares of several Indian companies. He sells the stock at a substantial gain in 2019 and is subject to Indian tax at the rate of 10%. That tax is fully paid.

Residence for Purposes Other than Foreign Tax Credit: Code §7701(b)(30)

Mr. Z is a U.S. resident under Code §7701(a)(30) for purposes other than the foreign tax credit. He is a Green Card Holder (i.e., a lawful permanent resident in the U.S.). As a result, Mr. Z is taxed on his worldwide income including the gain on the sale of stock of the Indian companies.

Residence for Foreign Tax Credit Purposes: Code §865

Mr. Z is a U.S. Green Card Holder (i.e., a lawful permanent resident). His principal place of employment is in the U.S. in 2019, the year in which the gain is recognized. He is treated as a U.S. resident for Code §865 purposes. The capital gain recognized by Mr. Z is U.S.-source gain. No portion of Mr. Z's U.S. tax liability relates to foreign-source income or gain. As a result, no portion of Mr. Z's tax can be offset by the foreign tax credit.

CAPITAL GAIN COMPUTATION

In both jurisdictions, the computation of the quantum of the capital gain is a function of the adjusted basis and the sale price.

U.S. – Adjusted Basis of Stock Depends on Form of Acquisition

Typically, the purchase price of the stock is the starting point for determining the adjusted basis in the shares. Additional capital contributions increase the basis. Distributions in excess of earnings and profits and redemptions of shares reduce the basis. If the shares are received as a gift, the recipient of the gift takes a carryover basis from the person making the gift. This means that the adjusted basis in the hands of the person making the gift becomes the adjusted basis for the recipient. If the shares are inherited from a relative or another person, the basis equals the fair market value of the shares on the date of death of the relative or other person. Once the adjusted basis is determined, the gross capital gain is the excess of the selling price over the adjusted basis. Expenditures made to effect the sale, such as commissions and fees, reduce the net sales proceeds, which in turn reduce the net capital gain.

India – Capital Gain Is the Excess of Selling Price Over Cost of Acquisition

As in the U.S., the purchase price paid for shares forms the adjusted basis in the shares. In a plain vanilla transaction, the taxable capital gain is the excess of the sales price over the adjusted basis, essentially the price originally paid by the seller to acquire the shares. The net capital gain is then reduced by the expenses that are incurred wholly and exclusively in connection with the sale.16 Typically, the commercially agreed price between unrelated parties is considered as the sale consideration. However, where the shares transferred are unquoted, minimum price requirements are applicable.

- The fair market value for tax purposes ("Tax F.M.V.") is determined pursuant to specified tax rules17 that form the minimum sale consideration for the seller.

- The excess of the Tax F.M.V. and the acquisition price is taxed as ordinary income in the hands of the purchaser.18

In addition, where the transaction is between related parties, the consideration is subject to the arm's length tests under Indian transfer pricing rules. As a result, the sale consideration for computation of capital gains in a related-party transaction is the highest of the following three values: (i) the commercial price, (i) the Tax F.M.V., and (ii) the arm's length transfer pricing value.

IMPACT OF HOLDING PERIOD ON THE TAX RATE

U.S.

Short-Term v. Long-Term Capital Gains

The tax rate imposed on an individual selling shares depends on the length of the holding period for the shares that are sold.

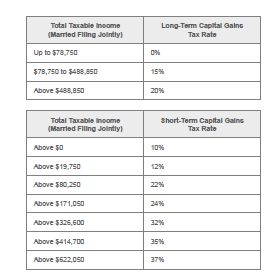

Gain from the sale of an asset held for at least 12 months and one day is subject to reduced tax rates of 0%, 15%, or 20%, depending on the taxable income and gain reported in the tax return for the year of the sale as well as the filing status of the taxpayer.

The gain from the sale of an asset held for not more than 12 months is characterized as short-term capital gain. It is taxed at ordinary income rates of up to 37%.

Tax Rates

For 2020, the tax rate brackets are as follows for a married individual who files a joint tax return with a spouse.

Net Investment Income Tax

Additionally, a U.S. resident is also subject to net investment income tax ("N.I.I.T.") at the rate of 3.8% on net investment income and gains. For a married individual who files a joint tax return with a spouse, the N.I.I.T. is imposed if the taxpayer's return reports $250,000 or more of modified adjusted gross income. Investment income includes interest, dividends, capital gains, rental and royalty income, non-qualified annuities, income from businesses involved in trading of financial instruments or commodities, and income from businesses that are passive activities to the taxpayer.

India

Short-Term v. Long-Term Capital Gains

The applicable tax rate on capital gains earned by a non-resident individual is dependent on whether the gains are characterized as short-term or long-term capital gains.

Where the shares of the Indian company are listed on a recognized stock exchange in India, capital gains are treated as long-term when the shares are held for a period of at least 12 months and one day before the date of transfer.19 If the holding period is less, the gain is characterized as short-term capital gain.

Where the shares of the Indian company are unlisted, capital gains are treated as long-term when the shares are held for a period of 24 months and one day. If the holding period is less, the gain is characterized as short-term capital gain.20

Tax Rates

For listed shares, the tax on long-term capital gains is 10%.21 The tax on short-term capital gains is 15%.22

For unlisted shares, the tax on long-term capital gains is 10%.23 Short-term capital gains are taxable at ordinary income tax rates.

The foregoing tax rates do not include the applicable surcharge and educational cess.

TAX PAYMENT MECHANISM

U.S. – Payment of Federal Income Tax Net of Foreign Tax Credit Due by Tax Return Filing Date

The individual will be liable to report the gain on the sale of the stock on Schedule D of Form 1040, U.S. Individual Income Tax Return, for the year in which the sale took place. Estimated tax is generally due in four installments throughout the year, and 90% of the ultimate tax due must be paid by the original due date of the return if an extension of the filing date is requested. In broad terms, the estimated tax payments must equal the lower of 100% of the prior year's tax or 90% of the tax that will be due ultimately for the year of the sale.

In Example 1, Mr. X will be subject to a U.S. tax of 20% (assuming the highest capital gain tax rate) and the N.I.I.T. at 3.8%. He will be able to claim the credit of the Indian taxes paid (10%) against his U.S. tax liability. He must file Form 1116, Foreign Tax Credit, with Form 1040. He will be liable to pay the N.I.I.T. thereby bringing his total U.S. and India tax liability on the sale to 23.8%.24

In Example 2, Mr. Z will be subject to a tax of 20% (assuming the highest capital gain tax rate) and the N.I.I.T. at 3.8%. No portion of his U.S. Federal income tax can be offset by a credit for the Indian taxes paid (10%). As a result, his net global income tax liability arising from double taxation will amount to 33.8%.25 Mr. Z will also be subject to state and local taxes, if any.

In both instances, the total cost will be increased by a surcharge and an educational cess, which combined range from 2% to 5% depending on the total taxable income in India. As explained in greater detail below, the Treaty will not provide any relief from double taxation.

India – Obligation on Purchaser to Withhold Tax

Indian income tax law imposes a withholding tax obligation on Indian residents making payments to non-residents.26 Generally, the seller provides a computation of capital gain realized, and on that basis, the purchaser withholds taxes from the payments to the seller.

Where the purchaser does not withhold and deposit applicable taxes, it is treated as a taxpayer in default of its tax obligations.27 The tax authorities can seek to recover the applicable taxes along with the interest and penalties. Alternatively, the purchaser may be treated as a representative assesse.28 As the seller's representative, the purchaser is at risk for all taxes, penalties, and interest owed by the seller.

IMPACT OF THE TREATY – TWO STEPS FORWARD AND THREE STEPS BACK

Article 13 (Gains) of the Treaty provides that each country may tax capital gains in accordance with its domestic tax law. The Treaty establishes the taxing rights of both countries. Paragraph 3 of Article 25 (Relief from Double Taxation) of the Treaty provides rules for determining the source of income for purposes of the foreign tax credit. It provides as follows:

(3) For the purposes of allowing relief from double taxation pursuant to this Article, income shall be deemed to arise as follows:

(a) income derived by a resident of a Contracting State which may be taxed in other Contracting State in accordance with this Convention (other than solely by reason of citizenship in accordance with paragraph 3 of Article 1 (General Scope)) shall be deemed to arise in that other State . . . . Notwithstanding the preceding sentence, the determination of the source of income for purposes of this Article shall be subject to such source rules in the domestic laws of the Contracting States as apply for the purpose of limiting the foreign tax credit.

At first glance, Article 25(3)(a) appears to provide that income derived by Mr. Z in Example 2, who is a U.S. resident (since he is a Green Card Holder), will be deemed to arise in India because it is taxed in India. However, this change in the source of income is immediately reversed, as the provision goes on to state that U.S. rules for determining the source of income for foreign tax credit purposes will control if they differ from the general rules stated in the Treaty. In other words, Article 25(3)(a) gives with one hand but takes away with the other. Consequently, going back to Mr. Z in Example 2, U.S. domestic tax law continues to apply, and as a result, the gain continues to be a U.S.-source income. As is apparent, the Treaty does not come to Mr. Z's rescue.

In these circumstances, the only possible remedy would be for Mr. Z to manage his facts to cause the gain to be foreign-source gain under both U.S. tax law and the Treaty. This can be achieved if Mr. Z were to dispose of his U.S. place of residence and move to a foreign country that either provides for a step-up in basis upon the establishment of residence, such as Canada, or that does not impose tax on offshore income of arriving residents or non-domiciled residents, such as the U.K., Switzerland, Portugal, Italy, and Cyprus. In these instances, careful planning is required to ensure that no hidden traps exist in the new place of residence that might prevent Mr. Z from enjoying the expected tax benefit. A re-entry permit should be obtained from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

Note, the goal is not to relinquish U.S. tax residence or renounce citizenship. It simply is to establish that Mr. Z in a non-resident within the meaning of Code §865(g)(2) for foreign tax credit purposes. The gain will continue to be taxable in the U.S. but will be treated as foreign-source gain because of the move. The Indian tax will continue to be imposed. However, since the tax rate should exceed the 10% threshold provided in Code §865(g)(2), Mr. Z can be treated as a non-resident for purpose of the sourcing rule under that provision. Mr. Z cannot have a place of abode available in the U.S. That is why the abode in the U.S. should be disposed of.

CONCLUSION

Like Mr. X, there are numerous taxpayers who are left with no relief at all and are subject to tax in both countries without any foreign tax credit. This is a classic example of what the tax treaties intend to avoid, yet the governments of the two countries have failed to address the issue. Therefore, given the varying tax implications in the U.S. and India for capital gains on the sale of stock of an Indian company, it is pertinent to undertake an in-depth analysis to evaluate the most tax efficient structure and to have certainty on the overall tax impact. The need to undertake analysis becomes more relevant considering that credit of taxes paid in India may not be available in the U.S., thereby resulting in double taxation. From an Indian tax perspective, one may consider investing through corporate structures in countries having favorable tax treaties with India.

Footnotes

1 Code §7701(b)(30).

2 Code §7701(b)(1)(A)(ii). An individual is said to meet the Substantial Presence Test in the current year if the individual is physically present in the U.S. on at least 31 days during the current year and 183 days during the three-year period that ends with the year in issue. In applying the 183-day test, days in the current year are given full weight. Those in the preceding year are given one-third weight. Days in the second preceding year are given one-sixth weight.

3 Section 5 read with Section 9 of Indian Income tax Act, 1961 ("I.T. Act").

4 Code §901.

5 Article 26 (Relief from Double Taxation) of the Treaty.

6 If the income is considered to be U.S.-source income for U.S. tax purposes, the foreign tax credit provides no relief (Code §904(a)). Unused foreign taxes may be carried back one year and carried over ten years (Code §904(c)) and may provide relief if excess limitation exists in the year to which the tax is carried.

7 Under paragraph 1(b) of Article 2 (Taxes Covered), the term "Indian Tax" means the income tax, the surcharge, and the surtax. It also includes o any identical or substantially similar taxes which are imposed after the date of signature of the Treaty. Under paragraph 1 of Article 25 (Relief from Double Taxation) those taxes are considered to be income taxes for foreign tax credit purposes.

8 Code §865(a)(1).

9 Code §865(a)(2).

10 Code §865(g).

11 Code §911(d)(3) and Treas. Reg. §301.7701(b)-2(c)(1). An individual has a tax home at a particular place if it is the individual's regular place of business or, if there is more than one regular place, if it is the principal place of business. If an individual does not have a principal place of business, the tax home is at the person's regular place of abode in a real and substantial sense.

12 Code §865(g)(2).

13 To determine whether the foreign tax paid meets the 10% hurdle, the amount paid is divided by the gain determined under U.S. tax concepts.

14 Code §865(g)(1)(B).

15 Paragraph 2 of Article 4 of the Treaty.

16 Section 48 of the I.T. Act.

17 Section 50CA of the I.T. Act read with Rule 11UA of the Income Tax Rules, 1962.

18 Section 56(2)(x) of the I.T. Act read with Rule 11UA of the Income Tax Rules, 1962.

19 Section 2(42A) of the I.T. Act.

20 Section 2(42A) of the I.T. Act.

21 Section 112A of the I.T. Act.

22 Section 111A of the I.T. Act.

23 Section 112 of the I.T. Act.

24 The surcharge and the educational cess, if applicable, should also be allowed as credit against Mr. X's U.S. tax liability because the cess is typically treated as "tax" in a U.S. sense and, therefore, meets the foreign tax credit eligibility requirement.

25 The surcharge and the educational cess, if applicable, will be an additional cost to Mr. X.

26 Section 195 of the I.T. Act.

27 Section 201 of the I.T. Act.

28 Section 160 read with Section 163 of the I.T. Act.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.