In a new staff report, the SEC Division of Economic and Risk Analysis considered the interconnections among six separate U.S. credit markets, and how three distinct types of stresses in each of the markets affected the products and participants during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The markets considered in the report include:

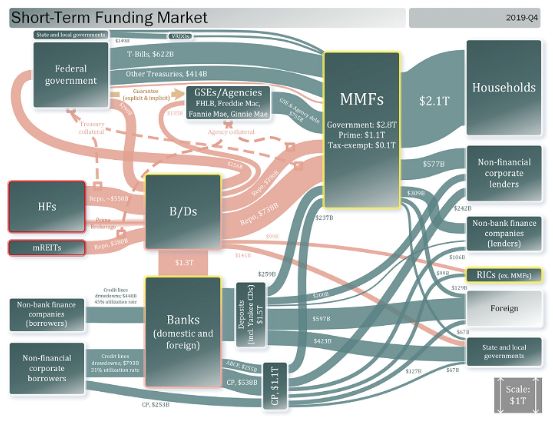

- Short-Term Funding Market. The short-term funding market contains several submarkets, including (i) repo financing, (ii) commercial paper, (iii) securities lending, (iv) prime brokerage, and (v) lines of credit.

- Corporate Bond Market. The U.S. corporate bond market is widely dispersed among insurance companies, registered investment companies, pension funds, and family offices.

- Leveraged Loans and the Collateralized Loan Obligation Market. Collateralized loan obligations ("CLOs") account for about half of the syndicated leveraged loans currently outstanding in the U.S., and as the market for leveraged loans has expanded, the risk profile of CLO pools has increased.

- Municipal Securities Market. The majority of municipal securities are relatively illiquid, and due to the effects of COVID-19, certain bonds (e.g., those backed by consumption taxes) face greater risk of impairment.

- Residential Mortgage Market. Federal agencies and government-sponsored enterprises ("GSEs") intermediate most residential mortgage debt, but retain the credit risk. Reliance on short-term funding from nonbanks is a particular risk in this market.

- Commercial Real Estate Mortgage Market. The entities that concentrate the most commercial real estate mortgage risk are banks (as the largest holders of such mortgages), followed by GSEs and insurance companies. Commercial real estate loans are often nonstandard mortgages with less stable future cash flows.

The types of market stresses that the SEC observed were divided into three categories:

- Short-term funding stresses resulting from an increased demand for liquidity and increased risk aversion.

- Market structure and liquidity-driven stresses resulting from an increased demand for dealers to take positions and intermediate trades.

- Long-term credit stresses resulting from general uncertainty as to the long-term economic impact of the virus.

SEC staff observed that:

- the demand for liquidity caused investors initially to sell U.S. government securities because, as the most liquid securities in the world, they were the easiest to turn into dollars without experiencing a loss; however, the market volatility and stress caused a substantial increase in bid-ask spreads;

- while dealers initially expanded their inventories of U.S. government securities, they hit their risk limits, which in turn limited their ability to provide liquidity to the market;

- declines in the prices for agency mortgage-backed securities "disproportionately and adversely" affected substantial holders of these instruments, given their very high ordinary levels of leverage;

- the commercial paper market largely froze, as there were many sellers and few buyers;

- there were substantial outflows from money market funds (other than U.S. government securities funds), which likely exacerbated problems in the commercial paper market; there were substantial inflows into U.S. government securities funds;

- trading volume in corporate bonds increased substantially, as did bid-ask spreads; and

- municipalities found it difficult to raise funds.

Commentary Steven Lofchie

For anyone interested in how the debt markets and the economy work, this is a must-read. The agency and the authors of the report should take a bow for turning out something in short order that is both understandable and useful as analysis.

While proponents of Dodd-Frank may believe that the legislation provided substantial safety benefits, that is not in fact so clear, or at least the picture is not so one-sided. In this regard, the report makes the following observations:

- were it not for intervention by the Federal Reserve, the market crash would have been much worse;

- U.S. derivative central counterparties ("CCPs") took in approximately $160 billion in additional initial margin, which may have made the CCPs safer, but also resulted in a substantial liquidity drain to the market generally, which concentrated credit risk in a very small number of legal entities; and

- sharp limits on dealer risk exposure amplified the need for the U.S. government to step into the markets as buyer in order to avoid a crash.

None of the above observations demonstrates the failure of Dodd-Frank or its success. Ultimately, risk has to go somewhere. The more that our regulations limit the ability of financial institutions to take on that risk, the greater the need for the U.S. government, in the person of the Federal Reserve, to absorb it, or, if it does not, the markets become more likely to crash.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.