The California electorate has approved Proposition 24, a statutory ballot initiative that substantially overhauls the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) enacted in 2018. Titled the "California Privacy Rights Act" (CPRA), Proposition 24 amends the CCPA by broadening its scope, enhancing the mechanisms for its administration and enforcement, and creating new obligations for regulated persons and entities at a time when many businesses had only recently come into compliance under the CCPA.

Proposition 24 faced opposition from both businesses and consumer advocacy groups. The former viewed Proposition 24 as undermining the deal reached on the CCPA by imposing additional compliance obligations and expenses so shortly after the CCPA's passage. And the latter either thought it did not go far enough or were otherwise concerned with what they viewed as business-friendly provisions. Specifically, some were concerned with the CPRA's "pay for privacy" program that permits businesses to offer rewards programs and discounts in exchange for consumers' consent to the collection of their personal information. Despite its complexity, the ballot initiative, as presented to the voters, had to be described in a few short sentences, such as:

Permits consumers to: prevent businesses from sharing personal information, correct inaccurate personal information, and limit businesses' use of "sensitive personal information," including precise geolocation, race, ethnicity, and health information. Establishes California Privacy Protection Agency. Fiscal Impact: Increased annual state costs of at least $10 million, but unlikely to exceed the low millions of dollars, to enforce expanded consumer privacy laws. Some costs would be offset by penalties for violating these laws.

The CPRA is a near-permanent statute that may be amended by the California Legislature only if such amendments are "consistent with and further the purpose and intent" of the Act. It will be extremely challenging for the California Legislature to amend the CPRA in any way that is perceived as decreasing-rather than increasing-privacy protections for consumers.

Key Substantive Amendments to the CCPA's Scope and Requirements

Regulated "Businesses"

The CPRA redefines "business" (a "business" being the principal regulated entity under the CCPA/CPRA) both to exempt smaller entities and to expand the types of businesses subject to its provisions by:

- Narrowing the scope of covered entities to exclude businesses that transact the personal information of less than 100,000 consumers or household, whereas before it was less than 50,000 consumers or households. Devices are also no longer considered businesses.

- Extending the applicability of the CPRA to businesses that derive 50% or more of their revenue from sharing, in addition to selling, personal information.

- Expanding the definition to include (i) joint ventures or partnerships composed of businesses that each have at least a 40% interest, and (ii) any person that transacts business in California and voluntarily certifies to the California Privacy Protection Agency (the Agency) that it is in compliance with, and agrees to be bound by, the CPRA.

Entities that are "businesses" under the revised "business" definition will have obligations not only with respect to consumers whose personal information they themselves collect, as is the case under the CCPA. The CPRA extends the obligation of a business to notify consumers about the collection, use, and disclosure of their personal information and their rights with respect to that information to each instance where the business controls the collection of the consumer's personal information, as opposed to only those instances in which the business itself collects such information.

Data Retention and Security

Currently, the CCPA does not impose requirements regarding data retention. With respect to data security, the CCPA created a private right of action for data security breaches resulting from a business' failure to use "reasonable security" measures to protect personal information, as required under another California statute, Cal. Civ. Code § 1798.81.5 (Section 1798.81.5). That preexisting California statute, however, requires "reasonable security" for types of "personal information" that comprise a narrow subset of what is defined as "personal information" in the CCPA (Cal. Civ. Code § 1798.140(o)).

The CPRA addresses both data retention and data security. It prohibits businesses from retaining personal information for longer than is reasonably necessary for the purposes disclosed to the consumer. Businesses also must notify the consumer of the length of time they intend to retain a consumer's personal information, or if that is not possible, the criteria used to determine such period.

With respect to data security, the CPRA provides that businesses must implement "reasonable security procedures and practices" to protect personal information from any unauthorized or illegal access, destruction, use, modification, or disclosure, "in accordance" with Section 1798.81.5. Given that Section 1798.81.5 applies to only a subset of what is "personal information" under the CCPA, it appears that the purpose of the CPRA "reasonable security" requirement is to extend a data security mandate to all "personal information" as defined in the CCPA; otherwise the requirement would be superfluous. Yet it is unclear why the CPRA provision includes the reference to "in accordance with Section 1798.81.5," particularly because the latter does not spell out specific types of "reasonable security procedures and practices" but rather simply requires such procedures and practices "appropriate to the nature of the information" -- which is precisely what the new CPRA provision states as well. The expansion of the types of information companies need to protect with "reasonable" security may not require significant investments in technical controls, given that the risk of harm to individuals from disclosure or loss of many of the new types of information covered is low. Still, companies likely will at least have to conduct a risk assessment for these new data types to ensure appropriate decision-making on what controls are "reasonable." Importantly, it does not appear that the new CPRA provision suggests any expansion of the CCPA's private right of action for data security breaches.

New rules governing the use and disclosure of sensitive information

The CPRA defines a new category of data, "sensitive personal information" (a term that roughly correlates to the EU General Data Protection Regulation's (GDPR) "special categories of personal data"), which includes government-issued identifying information such as Social Security and passport numbers, financial information, precise geolocation, race, ethnicity, religion, union membership, contents of mail and electronic communications, genetic data, biometric and health information, and information about sex life or sexual orientation. Sensitive personal information excludes both "publicly available information" (see below on the CPRA's expansion of that term), and information "collected without the purpose of inferring characteristics about a consumer;" if information would be "sensitive personal information" but for the fact that it is collected without the purpose of inferring a consumer's characteristics, it is treated a "personal information" under the CPRA.

Consumers have the right to opt out of a business' use of "sensitive personal information" in any manner beyond what "is necessary to perform the services or provide the goods reasonably expected by an average consumer who requests such goods or services." Businesses are required to provide consumers with a clear link on their internet homepage titled "Limit the Use of My Sensitive Personal Information" that enables them easily to exercise this right.

Expanded definition of "publicly available information"

Under the existing CCPA "publicly available" information, which is by definition not "personal information," consists solely of "information that is lawfully made available from federal, state or local government records." Consistent with other privacy laws, the CPRA broadens the definition of "publicly available" information to include "information [about a consumer] that a business reasonably believes is lawfully made available to the general public by the consumer or from widely distributed media, or by the consumer; or information made available by a person to whom the consumer has disclosed the information if the consumer has not restricted the information to a specific audience."

Additionally, the CPRA creates a new exemption from the definition of "personal information" for "lawfully obtained, truthful information that is a matter of public concern." Relying on this exemption, absent its clarification through regulations, could be at risk of challenge based on competing views of what are matters of "public concern."

Consumer rights to opt out of "sharing" of personal information

Expanding upon the CCPA, the CPRA provides consumers with the right to opt out not only of the sale of their personal information to third parties, but also to a business' sharing of their personal information. "Sharing" has a much narrower definition under the CPRA than under other privacy laws, much less any dictionary definition. Under the CPRA, "sharing" means: any form of transfer of a consumer's personal information "to a third party for cross-context behavioral advertising, whether or not for monetary or other valuable consideration." The term "cross-context behavioral advertising" is defined as "the targeting of advertising to a consumer based on the consumer's personal information obtained from the consumer's activity across businesses, distinctly-branded websites, applications, or services, other than the business, distinctly-branded website, application, or service with which the consumer intentionally interacts." Businesses that "share" personal information for such advertising will need to take the same types of steps to honor consumer's requests to opt out of such sharing as are currently required under the CCPA with respect to "sales" of personal information.

Requirement to honor consumer requests for correction of personal information.

Unlike many other privacy laws, the CCPA currently does not include an explicit requirement for businesses to honor a consumer's request for correction of the consumer's personal information. The CPRA will change this, requiring businesses to respond to such requests in a manner similar to responding to consumer requests for access to or deletion of personal information. In addition, as is currently required under the CCPA with respect to consumers' rights to request access and deletion, businesses will be required under the CPRA to inform consumers of their right to request corrections.

Roles of "contractors" and "service providers"; definition of "third party"

The CPRA modifies the definitions of third party and service provider and introduces the category of contractor. This eliminates the considerable ambiguity in the CCPA about the roles and responsibilities of service providers and third parties and the obligations of businesses related to disclosures of personal information to those entities. Under the CPRA:

- A third party is any entity other than a service provider, contractor, or the business the consumer intentionally interacts with.

- A contractor is a person to whom a business provides a consumer's personal information for a business purpose pursuant to a written contract. To meet the "contractor" definition, the recipient of the personal information must certify that it understands that it is prohibited from and will abide by its obligations not to: (i) sell or "share" the personal information, (ii) retain or use the personal information for any purpose other than the business purpose specified in the contract, (iii) disclose the personal information outside of the direct business relationship between the contractor and the business, or (iv) with limited exceptions, combine the personal information with any other personal information. An advertiser who generates behavioral profiles by aggregating personal information from multiple businesses is therefore effectively excluded from the definition.

- A service provider is a person that "processes personal information on behalf of a business" and receives that information from or on behalf of the business pursuant to a contract with the same contractual obligations as those of contractors as described above (although a service provider does not need to certify its understanding and compliance with these obligations).

The distinctions among these three types of entities clarifies the scope of the disclosures of personal information that must be tracked for purposes of informing consumers to whom those disclosures were made. As only disclosures to third parties must be so tracked, the CPRA clarifies that, provided that a business executes a contract with the recipient of personal information strictly limiting the recipient's use and disclosure of the information, the recipient need not be a service provider acting on behalf of the business to be exempt from the definition of third party. In short, it appears the contractor definition was created to account for sharing between businesses needed for a business purpose but not done by one on behalf of the other.

The CPRA makes explicit that businesses must convey consumer requests for correction, deletion, or limitation on the use of sensitive personal information to all service providers and contractors that possess copies of the relevant personal information, unless conveying the request is "impossible or involves a disproportionate effort." "Disproportionate effort," a term borrowed from the GDPR (and also used in the CPRA with respect to honoring requests to disclose personal information collected more than one year before the request was made), will be subject to the interpretation of the California Attorney General and/or the Agency.

Service providers and contractors have clear direct liability under the CPRA. They must cooperate with businesses in responding to a consumer's request to delete or correct personal information or to limit the use of sensitive personal information. However, they are not required to comply with a consumer request received directly from a consumer to the extent that such information was collected in their capacity as a service provider or contractor.

Implementation and Enforcement

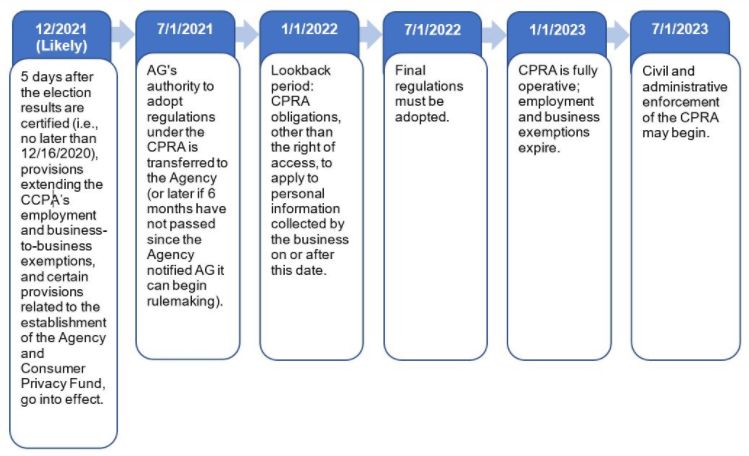

The CPRA will become law five days after California Secretary of State Alex Padilla files the statement of the vote for the election. However, like the CCPA (as well as the GDPR), the CPRA will not become fully effective or enforceable upon the date of its enactment. While certain provisions will be effective immediately, most provisions of the CPRA will not become operative until January 1, 2023. Among the provisions that will be immediately effective is an extension through January 1, 2023, of the exemption from certain CCPA requirements for personal information collected either in a business-to-business or an employee context (which otherwise would have expired on December 31, 2021),1 and provisions governing the allocation of funds by the newly created Consumer Privacy Fund.

California Attorney General Xavier Becerra is charged with continuing to implement regulations under the CCPA until the later of July 1, 2021 or six months after the Agency provides notice to the Attorney General that it is prepared to begin rulemaking under the CPRA. The Agency, the first agency of its kind in the United States, will have the full administrative power, authority, and jurisdiction to implement and enforce the CPRA (alongside the Attorney General). The CPRA will be governed by a five-member board comprised of two members elected by Governor Gavin Newsom, and three members each chosen by Attorney General Becerra, Speaker of the Assembly Anthony Rendon, and the Senate Rules Committee. Initial appointments to the board are expected to be made by March 16, 2021.

The Agency's final CPRA regulations must be adopted by no later than July 1, 2022, one year before the law becomes enforceable on July 1, 2023.

The overall timeline looks like this:

The maximum monetary penalties under the CPRA will remain the same as under the CCPA, with the exception of fines for violations knowingly involving personal information of consumers under age 16, which will triple (to $7,500) from those authorized under the CCPA. In addition, with respect to all actions other than private actions in data security breach cases, the CPRA eliminates the CCPA's 30-day "notice and cure" period. Thus, in any administrative action brought by the Agency or any civil action brought by the California Attorney General, a defendant will not have 30 days to, for example, amend its privacy policy to conform to all CRPA requirements, or to take other steps to come into CPRA compliance. Moreover, while private plaintiffs in data security cases will still be required to provide notice 30 days in advance of filing their complaint, the CPRA expressly provides that "[t]he implementation and maintenance of reasonable security procedure and practices pursuant to Section 1798.81.5 following a breach does not constitute a "cure" with respect to that breach." Some other form of "cure" will need to be demonstrated to avoid litigating the plaintiffs' claims.

Conclusion

As companies have worked to grapple with the challenges created by the CCPA, the CPRA introduces a new set of complex issues for businesses to evaluate and restrictions to which to adapt as they reformulate their privacy policies and institute programs to ensure compliance. Considering the breadth and nature of the changes that will be made pursuant to the CPRA, including its creation of the Agency, the CPRA may very well fundamentally alter the landscape of privacy regulation.

We will continue to monitor the implementation of the CPRA and are available to advise on steps to help ensure compliance.