The rarity of being a Black intellectual property lawyer in the United States hits home for the 1.7% of attorneys who fit that description.

"People are often surprised when they learn that I practice patent litigation," said Ellisen Turner, IP practice group partner at Kirkland & Ellis LLP. "When I introduce myself at conferences or events and give my elevator pitch, the surprise is often palpable."

In particular, say Black lawyers who have broken through, people are surprised they can speak the language of patent law and that many of them have attained scientific and technical knowledge.

As a junior associate, before going on to co-chair Venable LLP's IP division, Justin Pierce recalls hearing the trope about being "really articulate" from a potential client.

James Smith, the first chief judge of the federal Patent Trial and Appeal Board, and now chief intellectual property counsel at Ecolab Inc., said he's actually had attorneys hand him their bags to carry.

"I have seen, in my career, people who presume from the outset that I could not be handed much responsibility, because they didn't think I belonged in the responsibility-carrying club," Smith said.

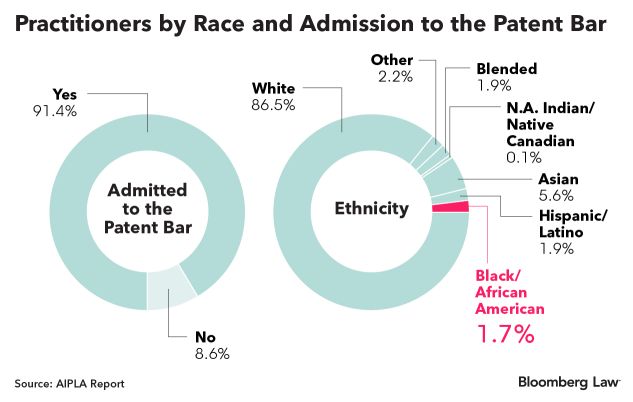

Apart from racism, Black IP attorneys say there are distinct reasons why they make up just 1.7% of their specialty, a figure based on a survey by the American Intellectual Property Law Association. By comparison, 5% of attorneys in the U.S. are Black, according to the American Bar Association.

Barriers in science education for Black students start as early as middle school, they say. There are a lack of visible Black mentors; for example, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, the nation's highest court for most patent cases, has never had a Black judge. Many Black law students aren't exposed to IP as a career path.

"Having people ahead of you who look like you and know what

you've been through, and can be the champions of your success,

can be critically important," Turner said. "That lack of

a pipeline of Black attorneys in this practice area certainly

hurts."

Lack of Visibility

Science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) education isn't required to practice IP law, including patent litigation. But more than 90 percent of American Intellectual Property Law Association survey respondents said they were admitted to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office bar, which is required to practice in agency matters like prosecuting clients' patent applications. STEM education, or practical experience verified by individual states, is a requirement to take that bar exam.

"When you look at that requirement, you must then consider the population of black college students, or post-college grads that have that technical background. So you're starting from a limited population to begin with," said Azuka Dike, a patent attorney at Banner Witcoff who is a liaison to the American Bar Association's Commission on Racial and Ethnic Diversity in the Profession.

Black IP lawyers have felt the impact of their race as early as their educational years.

As a graduate student at Johns Hopkins University, Gaby Longsworth remembers putting a batch of clean pipettes to dry in a laboratory oven in a hallway across from a propped-open bathroom door. A white male professor came rushing down the hall. Seeing a cleaning cart behind Longsworth, he asked, "Are you finished cleaning the bathroom?"

"I'd been in the department for three years and had seen that professor many times," said Longsworth, who went on to earn a doctorate. She's now a biotechnology and pharmaceutical partner at Sterne Kessler Goldstein & Fox PLLC and co-chair of the firm's diversity & inclusion committee.

Among the roughly 8% of students in ABA accredited law schools who are Black, many are first generation law students, and "may not have strong insight" regarding the structure of law school, Dike said. Often, key first year law courses leave no room for electives like intellectual property, meaning students may not get exposure to the subject matter.

University of Nebraska College of Law Professor A. Christal Sheppard was in her last year of completing a PhD in molecular biology before considering becoming a patent lawyer.

"There's a lack of visibility -- I wouldn't say I didn't know it existed, but it never occurred to me, as a career. No one brought up the possibility," said Sheppard, who was previously a director of the PTO's midwest regional office.

"Lawyers do XYZ. Lawyers go to court for criminals or

against criminals. That some lawyers have scientific backgrounds

and use them was not on my radar," she said.

Jonathan Hurtarte/Bloomberg

Law

Jonathan Hurtarte/Bloomberg

Law

Stronger Push

Some law firms are looking to increase the pipeline by going beyond recruiting from top law schools. Sterne Kessler, for instance, recruits technical specialists that are not lawyers from historically black colleges and groups like the Society of Women Engineers.

"You can start at some IP law firms in a technical specialist position, where you provide technical and scientific backup" to attorneys while learning the law, Longsworth said.

From there, a firm can pay for the candidate to take the patent office's bar exam, meaning the candidate can then help clients in the process of obtaining a patent. The person may go to law school and, in some instances, the firm covers the cost.

"You can't just wait until you have some applicants in law school to start diversity efforts," Longsworth said. "We do some outreach to undergrads, and even students in middle and high school."

Recruitment, said Joseph Drayton, a Cooley LLP partner and former National Bar Association president, should be followed with "proper training, access to premium work including repetition in assignments specific to patent matters, tracking of work and success in execution of assignments."

"Being laser focused on the opportunities afforded Black

lawyers and the outcomes will allow firms to course correct for any

potential disparate impact associated with long standing

practices," Drayton said.

Curveballs and Clients

Clients, attorneys say, are among the greatest gatekeepers for helping Black lawyers excel. Clients can push outside law firms to staff legal matters with diverse practitioners. Working on major trials, especially in a leadership role, opens the doors to more opportunities.

For Foley & Lardner LLP's Jeanne Gills, securing a lead role on a trial team in "one of the biggest cases" in her career -- a patent dispute in which a half-billion dollars were at stake -- was a game changer, made possible "because in house counsel lobbied for me."

"Any lawyer that hires outside counsel, they have the power to hire a diverse lawyer to lead their matter or require the lead lawyer to staff a diverse attorney," Gills said. "If such an individual doesn't exist at their law firm, say to them, 'If you want to keep my business, hire some additional individuals to put on my team."

But she also said Black attorneys like her have faced a "higher hurdle" when trying to secure client work.

Years ago, she said, a Black deputy general counsel at a Fortune 500 company got Gills a meeting with the outfit's White general counsel. "I could see the beads of sweat on his forehead, because he was probably like, 'Oh my God,'" Gills said, "Is my GC going to think she is fabulous?"

In an hour-long meeting, Gills was asked questions about a statute's legislative history, which had "nothing to do" with issues in the case. Gills, however, was "prepared for whatever curveball he could throw at me," and the GC decided to hire her on.

"He tested me, and I know I was judged and questioned in a way, if I were a white man, I would not have been," she said.

Pierce, the Venable lawyer who remembered being called "really articulate," said that occurred after an in-person presentation to a group of executives at a potential client company regarding a patent case. Beyond their behavior and comments being offensive, he said, they showed that "they made no effort in the past to seek out or meet with attorneys like me."

Now, he said, corporations need to "put their money where their mouth is" and stop claiming they can't find Black IP lawyers for a case.

"There are a number of talented African American attorneys, men and women, who for years now have represented clients," said Pierce, the former chair of the IP section of the National Bar Association, the largest national network of predominantly Black attorneys and judges. "When I hear that nowadays, my answer is, 'That's an excuse. You're not looking hard enough."

Originally published August 6, 2020.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.