Intellectual property (IP) is critical to the gaming industry. A video game is, at its heart, a collection of intellectual property rights. Whether you work for a pillar of the industry or are just starting out as an independent game developer, everyone should have a basic understanding of what these rights are, how they can impact your business, and how you may lose those rights. In the second of a series of papers exploring the basics of intellectual property law2 and its application to the gaming industry, we discuss one of the most well-known, but not always well-understood, types of intellectual property rights: Utility Patents.

I. What Are Utility Patents?

When most people talk about "patents," they are generally referring to what IP practitioners call "utility patents."3 As discussed in our previous whitepaper regarding design patents, a utility patent will protect a new and useful "machine, article of manufacture, composition of matter, or process." In short, a utility patent protects the way something works, as opposed to design patents that protect how something looks.

Put another way, a patent is a deal you make with the government. In exchange for disclosing how your invention works to the public, in the form of a patent, you get a monopoly. Importantly, the monopoly does not provide the owner the benefit to use or make the invention per se. For a set number of years (currently 20), you have the right to stop others from using your invention. But after that time is up, anyone can freely use your invention.

The scope of this right is governed by specific language found at the end of a patent: the claims. While the whole patent is important, a patent claim defines the exclusive right granted to the patent applicant. The other parts of the patent (such as the background of the invention, detailed description, and drawings/figures) exist to help the public understand what the invention is, and what the claims mean. In most cases, a patent will issue with multiple claims, each of which gives its own right to exclude others from using the invention.

This is a very powerful right—even with the time limit. For example, it is irrelevant if someone else independently developed the same invention after you. If a party uses at least one claim of the patent without your permission because the patent holder obtained protection on the invention first, he or she infringes your patent.

Figure 1: Mechanical Drawing of the D-Pad from US Patent No. 4,687,200

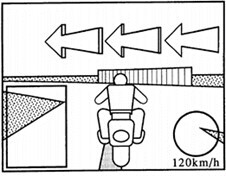

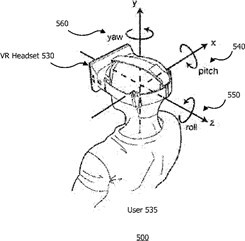

Figure 2: Drawing Depicting the Features of Crazy Taxi Arrow from US Patent 6,200,138

Notable past examples of utility patents granted in the video game industry include the globally recognizable D-Pad as well as the "Crazy Taxi" arrow that points players in the direction that they must navigate in a simulated world. More recent examples include patents covering augmented or virtual reality, such as U.S. Patent No. 9,063,330, assigned (at the time this whitepaper published) to Facebook. This patent is directed towards technology related to tracking the position of the user's head in the Oculus line of VR headsets.

Figure 3: Drawing Depicting a User Wearing a Virtual Reality System from US Patent 9,063,330

II. How Can Utility Patents Help My Company?

As mentioned above, a patent gives its owner a set of exclusion that is granted by the government for a limited amount of time in the country in which the patent was granted. Importantly, a patent does not give its owner the affirmative right to make, use, or sell the invention. Instead, it gives the owner the right to prevent others from making use of the invention (often called a "negative right" in the patent world). This negative right is how patents help inventors.

Since a patent excludes others from commercial exploitation of the invention, the patent holder is the only one who may make, use, or sell the invention. Others may practice the invention only with the authorization of the patent holder. Such authorization is usually given through a patent license agreement. A license agreement is a set of rules the patent owner sets that allows others to use the invention, often (but not always) in exchange for a fee or a share of any profits they get from doing so. Even where patent license agreements are given away for free, it can be very valuable to set the terms by which your invention is used.

Such a powerful right is not unlimited, however. For example, if an inventor wants to obtain patent protection, she must file for it sooner rather than later. Generally, an inventor will have a one-year grace period to file a patent once she has offered to sell a product using the invention, or within one year of any public use or disclosure of the invention. If you do not file the application, you may lose the ability to get any patent rights or protection for the invention. Therefore, it is a good idea to have a plan in place on how you want to handle patentable inventions even before you have invented anything.

As another example, enforcing the right to exclude is the patent owner's job. If someone makes, uses, sells, or imports your patented invention without your permission, he or she "infringes" the patent. Patent infringement is not a criminal offense; the government will not bring a case for you against the infringer. It is up to you as the patent owner to file a lawsuit against the infringer in Federal Court.

Litigation is complicated, but patent owners who win a lawsuit can look to recover multiple types of relief from the infringer. For example, patent owners may recover monetary damages. In addition, a patent owner may also obtain injunctive relief against an infringer. Injunctive relief is a court order that restrains the infringing party from doing certain acts, such as continuing to produce or import products that infringe.

While litigation is a common way for patent owners to prevent others from using their inventions without authorization, it is not the only way patents can be useful. Often, having a patent portfolio can be used defensively, to ward away others from accusing you of infringement. Patent rights can also be useful in negotiations with other companies, either as part of a "cross-licensing" agreement where each company lets the other use its patented technology, or as a way of getting better terms for some other deal. Furthermore, many investors use patents as a metric to understand the value of emerging technology, evidencing that the investment of time and money in development yields valuable results. If you are going to spend resources developing an invention, you owe it to yourself and your company to protect it.

III. How Do I Get a Utility Patent?

For many inventors, the process of obtaining a patent from the U.S. Patent Office ("USPTO") is daunting. It is often lengthy, and few patent applications are allowed after filing the initial application. Indeed, the process is so particular both attorneys and patent agents must take a separate "bar" exam to practice before the USPTO. If you think you might have a patentable invention, you should talk to a patent lawyer or agent to navigate these restrictions. Given the power of a granted patent, the process is often worth it.

At a high level, there are four main requirements you need to meet to obtain a patent: (1) the subject matter of the patent must be eligible for patent protection; (2) the invention must be "novel"; (3) the invention must be "useful"; and (4) the invention must be "non-obvious."

First, the subject matter of the invention must be eligible for a patent. Any claimed inventions must be one of either a "process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter" or an improvement of one of those four categories. While this list is quite broad, it is subject to an important list of exceptions: you cannot get a patent on an invention if it is a "law of nature," "natural phenomena," or an "abstract idea." In recent years, particularly after the seminal 2014 Supreme Court holding in Alice v. CLS Bank4, courts and the USPTO scrutinize software patents for attempting to protect "abstract ideas" being implemented on a generic computer. While the exact scope of the Alice decision and its implications is too complex for this whitepaper, anyone looking to patent an invention in the gaming space should be aware of the Alice decision, and you should discuss it with an attorney before filing a patent in the space.5

Once the subject of the invention has been deemed patent eligible, the invention must be "novel," "useful," and "non-obvious." In layman's terms, "novel" means that the invention, with certain specific exclusions, must not have been known or used in public before the filing of the patent application. If someone else disclosed the invention to the public first, you generally cannot get a patent.

"Useful" requires that the invention have a useful purpose. In most cases, the usefulness requirement is met in the context of computer and electronic technologies. The requirement is generally more important when at-tempting to patent something like a pharmaceutical or chemical compound, when the specific utility for the new compound is not as easily discerned.

Finally, "non-obvious" requires the invention not be an obvious improvement over some other existing invention that was previously known. In practice, this means that an inventor is not just combining two or more previously known inventions into one invention in an obvious fashion.

To consider novelty and obviousness, the USPTO reviews "prior art." Prior art is a catch-all term for evidence your invention might already be known (and not novel) or obvious. It usually takes the form of other patents, technical papers, or even earlier products or systems.

If you think your invention meets these requirements, the first step of getting your patent is to file a patent application. Filing your application is a major milestone, and usually sets what is called your "priority date," or the earliest filing date a patent application can claim. Prior art that comes before this date might "invalidate" the patent in court, or the USPTO may not grant the patent during examination. If you are applying for a patent, you want to get the earliest priority date you can.

If you are concerned about the cost or time involved to get a patent, you can file what is called a "provisional" patent application to establish that date, instead of a full "non-provisional" patent application. A provisional patent application does not require the same amount of information required for a non-provisional application and gives you a year to follow-up with a non-provisional patent application but still claim the earlier priority date. They are a quick and inexpensive way for inventors, especially smaller inventors (like independent developers), to secure their rights while determining if the cost of obtaining a full patent is worth it. Another benefit of the provisional application is that it allows you to advertise your technology as "patent pending."

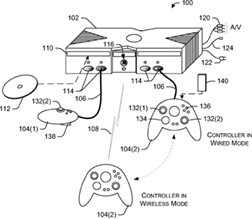

Figure 5: US Patent US8727882B2 for a Wired and Wireless Controller, assigned to Microsoft

Once filed, an employee of the USPTO called the "examiner" will determine if the application should issue as a patent. The examiner will consider all the patent requirements, including conducting a search through numerous databases to make sure that the claimed invention does not overlap prior art as discussed above. If the examiner identifies issues, she will notify the applicant, who gets a chance to respond, by changing what the claims say or explaining how the invention is patentable as described in the patent application over that prior art. This process typically involves multiple back and forth communications with the examiner, but once the examiner is convinced, the patent issues.

Though the process can take a long time, it is still something worth considering in a fast-moving industry like gaming. On average, it takes anywhere from one to five years from the filing date of the non-provisional application before the patent issues. The scope of protection, however, is broad, lasts a long time, and is additive. Since a patent is a right to exclude, not a right to operate, a truly innovative invention is valuable long after the game or system it was developed initially to support become obsolete if it is incorporated as a building block for future games or systems.

IV. How Can My Company Look For Patenting Opportunities?

In evaluating whether a utility patent is appropriate for an invention, game developers should consider whether an underlying process or software overcomes a specific problem that has plagued the industry writ large. Inventions that solve major industry problems are appropriate for patent protections, especially if it will be impossible to keep them a secret (trade secrets will be the subject of a future whitepaper). These innovations can also have applications beyond just the current generation of gaming, making a patent potentially valuable for its full term.

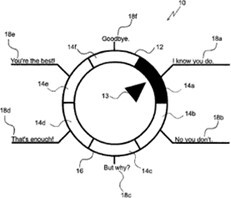

Figure 9: EA's Patent No. 8,082,499 covers the dialog wheel that has been prominently featured in many RPGs, including the Mass Effect series

From an eligibility perspective, developers should keep the core holdings of Alice in mind when attempting to patent a software invention and ask if the claimed invention brings about any specific improvements to currently existing software, or if it is otherwise directed towards the "abstract" or "law of nature" categories. Additionally, developers should make sure to emphasize their claimed invention's improvements upon already existing technology to avoid the "obvious" or "non-novel" category.

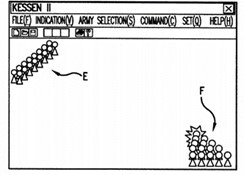

Figure 8: Koei's Patent No. 6,729,954 covers the ex- pression of uneven attack power on large groups of enemies by a player character and is utilized in its Dynasty Warrior series

Given the complex rules and regulations involved in utility patent law, developers should also consider consulting with patent attorneys who understand the legal requirements for obtaining a utility patent. Besides helping clarify if an invention should qualify for patent protection, good patent attorneys may also help suggest additional ideas and avenues for protecting the invention as well as how best to maximize the profitability of a developer's intellectual property portfolio.

Footnotes

1 These materials have been prepared solely for educational and entertainment purposes to contribute to the understanding of intellectual property These materials reflect only the personal views of the authors and are not individualized legal advice.

2 Please note that this series of papers focuses on the intellectual property laws of United States. Other countries often have their own versions of these intellectual property rights, though the rules can be, and are usually, different. You should consider the laws of any country in which you plan to make, use, or sell your game when considering intellectual property Further, for those located outside of the United States, if you plan on selling games within the United States, you should still become familiar with its intellectual property laws and seek out protection where appropriate. Foreign entities may obtain intellectual property protection in the United States.

3 ll refer to utility patents as patents throughout the rest of this whitepaper.

4 Alice Corp. CLS Bank International, 573 U.S. 208 (2014)

5 In Winter 2020, we provided IGDA with a webinar regarding Alice and patent eligibility.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.