On July 18, 2023, the Federal Trade Commission and the US Department of Justice issued a draft of their much anticipated Revised Merger Guidelines. The revisions are the first update to the agencies' horizontal merger guidelines in over thirteen years and the first guidance on vertical mergers since the 2020 Vertical Merger Guidelines were withdrawn in 2021. The Revised Guidelines reflect the more aggressive and novel theories of harm that the agencies are currently using to analyze mergers and acquisitions, and, in several ways, reflect a substantial departure from and expansion of the 2010 Horizontal Merger Guidelines.

In summary:

- The Revised Guidelines attempt to return merger enforcement to some of the standards articulated by the agencies in their first Merger Guidelines from1968. The 2010 Guidelines used market shares and concentration statistics as a starting point for the agencies' analysis. The Revised Guidelines, however, take antitrust "back to the future" — the agencies will now deem a broader range of mergers to be presumptively unlawful.

- The Revised Guidelines expand on the 2010 Guidelines in several areas. The Revised Guidelines explain how the agencies will analyze mergers involving potential competition, competition for employees, and technology platforms. Transactions involving "dominant" firms and platforms will receive special treatment and enhanced scrutiny under the Revised Guidelines. The Revised Guidelines also address vertical mergers and non-vertical mergers that might disadvantage the merging parties' competitors.

- The Revised Guidelines do not eliminate the consumer welfare standard or the use of economic analysis in determining a merger's effects. Rather, by relying on a series of presumptions to determine a merger's legality, the agencies can replace their own economic analysis with less burdensome evidence—e.g., measures of and trends in concentration; a firm's history of prior transactions; or ordinary course business documents. The practical effect is to shift the economic analysis to the merging parties, who must prove that the merger does not harm competition. In practice, however, the merging parties already confront this challenge.

Overall, the Revised Guidelines suggest that more transactions will require more time to complete. This has practical implications for a deal's terms, such as longer outside dates and stronger commitments to litigate. The ultimate decisionmakers, however, remain the federal district courts. Unlike other jurisdictions, US antitrust agencies cannot unilaterally stop a merger; they are required to seek judicial intervention. Over the last two years, the agencies have tested some of the proposed changes to the Guidelines before district court judges, with mixed results. District courts have been unwilling to credit novel theories that the agencies are unable to support with persuasive evidence. The takeaway, so far, is that well-prepared merging parties with strong evidence continue to consummate their deals.

Presumptions and Trends Emphasized Over Economic Analysis

The Revised Guidelines move away from the 2010 Guidelines approach—which focused on evaluating the economic effects of a merger—in favor of market share presumptions. Overall, they signal that the agencies are more likely to challenge a range of proposed deals that may have been approved under the 2010 Guidelines.

Changes Applicable to All Deals

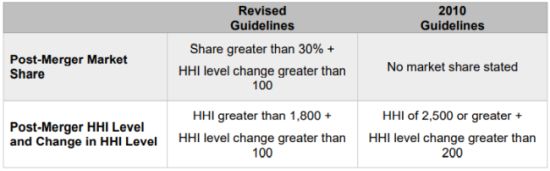

- Presumption of Illegality at Lower Levels of

Concentration: The Revised Guidelines employ a lower

threshold for post-merger concentration that would trigger a

presumption of illegality. Under the Revised Guidelines, a merger

is presumptively unlawful if (i) the parties' post-merger share

is greater than thirty percent and the post-merger change in HHI is

greater than 100; or (ii) the postmerger market is highly

concentrated—defined as an HHI exceeding 1,800—and the

post-merger change in HHI is greater than 100.1 This

structural presumption appears to hold for both horizontal and

vertical mergers. The agencies' use of a specific market share

as a threshold is a first in the fifty-five-year history of the

Merger Guidelines, while the lower HHI threshold marks the

agencies' return to the thresholds that predated the 2010

Guidelines. The table below compares the structural presumptions

under the Revised Guidelines to those under the 2010

Guidelines.

- Size Matters: A merging party with a thirty percent or higher market share (a "dominant firm") can expect to receive additional scrutiny under the Revised Guidelines. The agencies will assess whether the merger permits the "dominant firm" to extend its "dominant position" into a related market, or whether the merger further entrenches the firm's already "dominant position" in the relevant market. Under the Revised Guidelines, mergers that extend or entrench a "dominant position" are presumptively illegal under the Clayton Act Section 7, and possibly under Section 2 of the Sherman Act. District courts typically require higher market shares to conclude that a firm is "dominant."2

- Emphasis on Trends Toward Concentration: In addition to a "snapshot" of market concentration measured by HHIs, agencies will also consider whether the merger occurs in a market or industry where "there is a significant tendency toward concentration." This trend toward concentration may be horizontal or it may relate to vertical integration. The agencies state that a "tendency toward concentration" may be present where market HHIs exceed 1,000 and rise toward 1,800, or where other market characteristics are present, like the exit of significant market participants. The Revised Guidelines mark the first time since the 1968 Guidelines that the agencies have identified a "tendency toward concentration" as a potential factor in determining a merger's legality.

- Greater Scrutiny of Mergers Between Potential Competitors: Under the Revised Guidelines, potential competition concerns might arise if there is a "reasonable probability" that a firm will enter and compete with the other merging party. The agencies take the position that an ordinary course business document discussing the possibility of future entry can be evidence of "reasonable probability." The Revised Guidelines state that even the perception that a merging firm is a potential entrant by other market participants may be sufficient to show a transaction will substantially lessen competition; it is not necessary for those participants to have changed their behavior in response to that perception.

- Rivals Gain Seat at the Table: Under the 2010 Guidelines, the agencies did "not routinely rely on the overall views of rival firms regarding the competitive effects of the merger." The Revised Guidelines take a different position. Now, the agencies will consider whether the merger will make it harder for rivals to compete—even if those rivals do not buy products or license technology from either of the merging parties.

- Vertical Mergers Face Enhanced Scrutiny: Vertical mergers that enable the merged firm to foreclose rivals from inputs, customers, or services that are necessary for the rivals to compete create competitive concerns. Under the Revised Guidelines, mergers that result in foreclosure shares greater than fifty percent are presumptively unlawful.3 When foreclosure shares are below fifty percent, the agencies will consider a series of "plus" factors, such as a trend toward vertical integration; the nature and purpose of the merger; whether the market is already concentrated; and whether the merger increases the barriers to entry.

- No Cross-Market Balancing of Harms and Efficiencies: The Revised Guidelines reject crossmarket balancing—the weighing of harms in one market against efficiencies in another. Previously, under the 2010 Guidelines, the "Agencies in their prosecutorial discretion [could] consider efficiencies not strictly in the relevant market."

Changes Applicable to Certain Industries or Deal Structures

- Platforms Get Special Treatment: The Revised Guidelines are the first to provide specific guidance on mergers in platform industries. A platform creates value by connecting two or more distinct groups of customers. Where a given transaction involves a platform, the agencies will consider competition (1) between platforms; (2) on a platform; and (3) to displace a platform. Moreover, the Revised Guidelines distinguish the agencies' analysis from the Supreme Court's approach in Ohio v. Amex4: rather than requiring evidence of harm to both sides of the platform, the agencies may define the relevant market to encompass only one side of a platform.

- Partial Ownership Acquisitions: The Revised Guidelines make subtle changes that impact the analysis of acquisitions involving partial control and common ownership. Under the Revised Guidelines, acquisitions of partial or common ownership will no longer require a "distinct analysis" and will be subject to the same competitive analysis as transactions that result in full ownership. The Revised Guidelines warn that acquisitions of partial or common ownership may cause harm by diminishing the incentive of the commonly owned businesses to compete.

- Institutional Investors and Private Equity Acquisitions: While not mentioning institutional investors or private equity by name, the Revised Guidelines contain provisions that impact these business entities. The agencies will investigate the "cumulative effect" of multiple small acquisitions for business entities that exhibit a "pattern or strategy of growth through acquisition."

Unknown Impact of the Revised Guidelines on Merger Law

The Revised Guidelines, once implemented, will not have the force of law. They are a statement of how the agencies apply the law in their merger investigations. Whether the courts adopt the Revised Guidelines remains to be seen. The Revised Guidelines primarily rely on Supreme Court and circuit cases from the 1960s and 1970s. When courts evaluate merger challenges, however, they are likely to also consider more modern merger case law, much of which is less favorable to the agencies. As now-Justice Kavanaugh observed while on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit:

[Courts are] bound by [the Supreme Court's decision in] General Dynamics, not by the earlier 1960s Supreme Court cases.... Under the modern approach reflected in cases such as General Dynamics...the fact that a merger...would produce heightened market concentration and increased market shares...is not the end of the legal analysis. Under current antitrust law, we must take account of the efficiencies and consumer benefits that would result from this merger. Any suggestion to the contrary is not the law.5

Implementation Timeline

The agencies have invited the public to submit comments on the Revised Guidelines by September 18, 2023. After reviewing those comments, the agencies may opt to implement further revisions to the Guidelines. Unlike the proposed new HSR Disclosure Requirements, however, the Guidelines are not a rulemaking. As a result, the agencies are not required to consider public comments before issuing the final version.

What Merging Parties Can Do Now

Although the Revised Guidelines are in draft form, merging parties should treat them as evidence of the agencies' current and future approach to merger enforcement and take the following steps:

- Take Precautions When Creating Documents: Ensure that employees are aware that documents of all types, created for any purpose, may be subject to greater scrutiny. The Revised Guidelines demonstrate that the agencies are considering a wider range of theories of harm. Statements that were once acceptable may now trigger scrutiny by the agencies.

- Plan Ahead: Engage with antitrust counsel early and often. The Revised Guidelines, in combination with the proposed new HSR Disclosure Requirements, caution for earlier and enhanced assessments of antitrust risk at the outset of deals. Certain transactions may now require greater advocacy during the days before and following an HSR filing.

- Carefully Evaluate Synergies and Other Merger Benefits: The Revised Guidelines warn of potential harms that might flow from certain deal synergies, such as harms to rivals, suppliers, and employees. This cautions for a disciplined approach to explaining how a merger will affect those constituents.

- Prepare Strong Procompetitive Deal Rationale: The Revised Guidelines' consideration of a merger's impact on the parties' rivals means complaints from the parties' rivals will find a receptive audience at the agencies. Anticipating rivals' reactions and preparing a strong procompetitive rationale for the deal will be important.

- Play the Long Game: Greater antitrust scrutiny of M&A transactions is here to stay. Although the agencies have recently experienced mixed results in court, the agencies appear committed to pursuing the enforcement objectives articulated in the Revised Guidelines.

We will continue to keep you apprised of developments regarding the Revised Guidelines.

Footnotes

1. The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) is a measure of market concentration calculated by summing the squares of the individual firms' market shares of the relevant market.

2. See, e.g., U.S. v. Dentsply Int'l, 399 F.3d 181, 186–87 (3d Cir. 2005) (requiring a market share between 75 to 80 percent); Image Tech. Servs. v. Eastman Kodak Co., 125 F.3d 1195, 1206 (9th Cir. 1997) ("Courts generally require a 65% market share to establish a prima facie case of market power.").

3. The foreclosure share is the share of the related market that s controlled by the merged firm.

4. Ohio v. Am. Express Co., 138 S. Ct. 2274 (2018).

5. See U.S. v. Anthem, Inc., 855 F.3d 345, 376–77 (D.C. Cir. 2017) (Kavanaugh, J., dissenting) (discussing U.S. v. General Dynamics Corp., 415 U.S. 486 (1974)).

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.