On January 1, 2016, the world's seventh largest economy, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations ("ASEAN"), inaugurated the ASEAN Economic Community ("AEC"). The AEC aims to create a single market and production base for the free flow of goods, services, investment, capital, and skilled labor within ASEAN. The new Community offers expanded opportunities and inevitable challenges for multinationals investing in this diverse but often opaque market.

Figure 1: The ten ASEAN member countries.

Background on ASEAN and the AEC

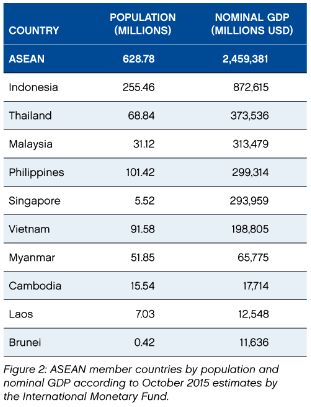

ASEAN was first formed in 1967 by Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand. Since then, ASEAN has added Brunei (1984), Vietnam (1995), Laos (1997), Myanmar (1997) and Cambodia (1999). Although ASEAN's ten member economies are in various stages of development, it has a combined population larger than the European Union, a combined gross domestic product of $2.5 trillion, and average economy growth rates of between 4 to 7 percent.

ASEAN embraces a philosophy known as the "ASEAN Way," by which countries approach problem solving through informal compromise, consensus, and noninterference. These principles —rooted in each state's sovereignty, integrity, and identity—have resulted in slow development and difficult consensus building for ASEAN goals. Comparisons between ASEAN and the European Union ("EU") are frequent but probably, at best, premature. For instance, whereas the EU has focused on fuller integration, with a continent-wide currency and visa-free travel, ASEAN has focused on issues such as regional peace and economic development.

In 2007, ASEAN developed its Blueprint for the ASEAN Economic Community. The Blueprint identified four "pillars" of the AEC to create a single market and production base, a competitive economic region, a region of equitable economic development, and a globally integrated regional economy. In the subsequent eight years, the implementation of the AEC has been a work-in-progress. Numerous trade and economic treaties have been proposed or ratified, but the organization has faced delays in ratification of many agreements, and some states have been slow to adopt enacting legislation domestically. Cross-country development and efficiency gaps continually threaten AEC goals (because, for example, of fears of brain drain or a race to the bottom), and cross-cultural and political differences have proven irreconcilable with consensus building.

Despite these obstacles, the ASEAN members agreed to form the AEC—effective January 1, 2016—with the continued goal of realizing the four pillars in the original Blueprint. As the AEC continues to mature, opportunities will arise for companies looking to expand in or into the Southeast Asian market. Indeed, foreign direct investment is one of the publicly-stated priorities for the AEC.

Cross-border Business Opportunities

As intra-ASEAN collaboration increases, the AEC will start to realize goals of unifying the region's production base, particularly with policies such as free movement of goods and services and the elimination of cross-border tariffs. China's increasing labor costs and economic slowdown may make the AEC region increasingly attractive to potential investors.

For example, the ASEAN nations individually have a diverse set of structural capabilities, natural resources, and labor skills. Singapore has emerged as a financial and legal powerhouse that offers easy access to investor capital and a well-established legal system known for its rule of law. Countries like Indonesia have extensive natural resources in a variety of sectors, while Vietnam, Myanmar, and Cambodia still maintain attractive labor markets. As cross-border trade continues to increase and tariffs continue to loosen, companies should consider the AEC as an opportunity to integrate production processess and take advantage of each country's unique resources and abilities.

The AEC may allow for increasingly creative corporate structures. As some examples, companies can establish a series of specialized subsidiaries in the various ASEAN countries, which may include a regional headquarters and/or joint ventures with local businesses. With reduced cross-border tariffs and free movement of goods, such structures can realize the comparative advantages that each country has to offer.

Ultimately, these opportunities will depend on the AEC's ability to address cross-legal and cross-cultural differences among the member countries. While the individual countries have different strengths within a single marketplace, many of them have local restrictions or prohibitions on foreign ownership of locally incorporated entities. Additionally, variations in the regulation of corporate affairs such as shareholder, capital, and even language requirements will all present challenges in pan-regional corporate structures.

As it matures, the AEC may continue to see cross-border simplification with issues such as incorporation requirements, multilingual applications, and standardized procedures, and companies should continue to monitor developments in the AEC as potential opportunities for streamlining and economizing across entities.

Cross-border Public Offerings

In 2004, the Finance Ministers of ASEAN formed the ASEAN Capital Markets Forum ("ACMF"), a group of market regulators from the ten ASEAN member states. Originally, the ACMF aimed simply to harmonize the various national rules and regulations. Since the development of the AEC Blueprint, the ACMF has shifted focus toward full integration of the region's capital markets.

In the decade since its composition, the ACMF has had some discrete accomplishments. Since August 2014, Malaysia, Thailand, and Singapore have allowed fund managers to offer collective investment schemes with streamlined authorization processes. In September 2015, the ACMF announced a "Streamlined Review Framework for the ASEAN Common Prospectus." Covering the Singapore, Kuala Lumpur, and Bangkok exchanges, the initiative allows issuers of equity or debt securities a streamlined review process that cuts time-to-market and thus provides faster access to capital.

With the inauguration of the AEC, the ACMF now looks to its Action Plan 2016–2020, which outlines objectives for an increasingly interconnected region. More specifically, ACMF goals include full implementation of the Common Prospectus and increased liberalization of the financial services sector, as well as liberalization of industry practices such as payment and settlement mechanisms.

The ACMF has made progress in Singapore, Malaysia, and Thailand, but investors should be aware that full AEC integration will be a challenge. The AEC includes ten very different markets with often divergent attitudes toward free market values, foreign involvement, and taxation. Harmonization of securities laws, financial reporting, and disclosure requirements is still a long way off. So while companies may access cross-border exchanges with increasing ease on the one hand, they may still face distinct and possibly conflicting laws and regulations on the other.

Intellectual Property Protection

Alongside the AEC's goals of free movement of goods are concerns for intellectual property right ("IPR") protection for those goods. By 2011, ASEAN recognized the need for enforced IPR and developed five strategic goals: (i) a balanced IP system that takes account of the member states and their levels of development, (ii) development of legal and policy infrastructures to make ASEAN a global participant in IP development, (iii) promotion of IP creation, awareness, and utilization, (iv) regional participation in the international IP community, and (v) increased cooperation for IPR among the ASEAN states.

Unlike the EU, ASEAN has not yet given serious consideration to pan-regional trademark, copyright, and patent protections. However, ASEAN has undertaken efforts to harmonize regulation of particular industries such as cosmetics and pharmaceuticals, and local companies in these sectors have successfully built IP-dependent businesses. In addition, in the last year, ASEAN countries have begun to accede to various international agreements that point to a common patent application (the Patent Cooperation Treaty) and a common trademark application (the Madrid Protocol). Such acceptance offers hope that AEC cooperation on the development of IPR will give rise to standardized principles, if not legal regimes.

Until then, businesses should consider seriously which markets they intend to enter as well as applications for protection in all relevant jurisdictions for trademarks, patents, and copyrights. They should pay due attention to the robustness of the individual countries' IP regimes, their patterns of enforcement, the judicial infrastructure for this enforcement, and varying but developing cultural respect for IPR.

Dispute Resolution

As divergent as any is the issue of conflict resolution within ASEAN. Member countries vary fundamentally in their sources of law: Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Vietnam, and Thailand follow civil law; Singapore, Malaysia, and Myanmar have inherited English common law precedent, supplanted with local legislation and decision-making; and Brunei uses a dual system of Sharia and common law. Many perceive Singapore as having the most transparent and respected legal system in the region, while in other countries practitioners worry about whether any hard-fought judgment is actually enforceable.

Given the divergent legal systems and protections, investors have sought dispute resolution through arbitration, particularly in the area of investor-state conflicts. These relationships are frequently governed by bilateral investment treaties ("BITs"), multilateral investment treaties ("MITs"), or free trade agreements ("FTAs"), which confer certain rights and remedies to investors aggrieved by their host countries. Typically, these instruments refer investor-state disputes to arbitration, and various ASEAN agreements require such arbitrations to be seated in regional centers such as Kuala Lumpur and Singapore.

While these agreements can offer valuable protections to businesses and investors, they must rely on the ad hoc network of investment treaty pacts – of which there are more than 3,000 worldwide – and the unpredictability of potentially varying terms among them. Even with investment treaties in place, businesses cannot assume that they are static or permanent regimes: in 2014, for example, amid complaints that investment treaties overly favored foreign investors to local interests, Indonesia announced plans to terminate over sixty of its BITs.

ASEAN has taken some steps toward regional solutions and multilateral agreements. Signed in 2009, the ASEAN Comprehensive Investment Agreement ("ACIA") allows investors (under specific conditions covering limited industries) to arbitrate against their host countries by submitting claims to various regional and international bodies. While the ACIA may provide some comfort to foreign investors in ASEAN, the development of regional and consolidated dispute resolution mechanisms – like IPR protection – clashes against ASEAN values such as noninterference and national sovereignty and remains an ongoing goal.

The patchwork of treaty-based investor protections, the complexity of the region's various legal regimes, and recent movement toward regionalized dispute resolution each require caution. Companies should thoroughly consider the available protections in the local country, and they should continuously evaluate how disputes are resolved. Companies should also monitor developments in the ACIA and other dispute resolution mechanisms and amend, as necessary, their dispute resolution mechanisms with counterparties to take advantage of developments in the law and to protect their businesses and investments within ASEAN.

Singapore: Stability in a Developing Region

Many of the AEC member countries still face significant challenges in recognizing, developing, and enforcing the rights of investors. For example, in a widely criticized case, the Indonesian high court recently nullified a cross-border loan agreement between two private parties because the contract did not have an Indonesian-language counterpart. Myanmar is frequently criticized for rampant corruption, political cronyism, and rent-seeking behavior. Companies looking to do business in Southeast Asia often find the predictability and strength of legal regimes in the region lacking.

By contrast, Singapore is widely heralded for its respect for the rule of law. The World Bank's "Doing Business" report ranks Singapore as its top of 189 countries, with strengths in the enforcement of contracts and the protection of minority investor rights. Transparency International's "Corruption Perceptions Index" ranks Singapore as the least corrupt country in Asia and seventh worldwide.

The introduction of the AEC is an important milestone toward an integrated ASEAN market. The AEC has a full agenda of discrete and meaningful steps toward realizing its goal of a single marketplace, and international businesses should be rightfully optimistic about expanding opportunities in the region. As the AEC finds its way to a true single market, companies will continue to look to Singapore as a prime location from which to take advantage of those opportunities.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.