Looking Back

2012 gave us another year of aggressive enforcement of insider trading laws. The Department of Justice ("DOJ") extended its perfect record at trial, including a verdict against the former chief executive of McKinsey & Co. and Goldman Sachs board member Rajat Gupta - the most high-profile defendant to date. Through 2012, the government continued its pursuit of hedge funds and their sources of inside information, including expert networks.

As the Rajaratnam and Gupta cases geared up for appeals, the slew of cooperators ensnarled in the investigations began to be sentenced and to have penalties assessed against them by the Securities and Exchange Commission ("SEC"). The sentences handed down were often far below the Sentencing Guidelines range and below what the government had requested. 2012's sentences solidified the growing notion that cooperation with DOJ may be a defendant's best chance of attaining a "get out of jail" card.

The increase in insider trading enforcement was not limited to US regulators. In 2012, agencies worldwide showed increased policing and prosecuting of insider trading.

And just as the year was winding down, regulators found their likely next target for insider trading enforcement: executives' trades under 10b5-1 trading plans.

OVERVIEW OF INSIDER TRADING LAW

"Insider trading" is an ambiguous and over inclusive term. Trading by insiders includes both legal and illegal conduct. The legal version occurs when certain corporate insiders - including officers, directors and employees - buy and sell the stock of their own company and disclose such transactions to the SEC. Legal trading also includes, for example, someone trading on information he or she overheard between strangers sitting on a train or when the information was obtained through a non-confidential business relationship. The illegal version - although not defined in the federal securities laws - occurs when a person buys or sells a security while knowingly in possession of material nonpublic information that was obtained in breach of a fiduciary duty or relationship of trust.

Despite renewed attention in recent years, insider trading is an old crime. Two primary theories of insider trading have emerged over time. First, under the "classical" theory, the Securities Exchange Act of 1934's ("Exchange Act") antifraud provisions apply to prevent corporate "insiders" from trading on nonpublic information taken from the company in violation of the insiders' fiduciary duty to the company and its shareholders.1 Second, the "misappropriation" theory applies to prevent trading by a person who misappropriates information from a party to whom he or she owes a fiduciary duty - such as the duty owed by a lawyer to a client.2

Under either theory, the law imposes liability for insider trading on any person who improperly obtains material nonpublic information and then trades while in possession of such information. Also, under either theory - until 2012 - the law held liable any "tippee" - that is, someone with whom that person, the "tipper," shares the information - as long as the tippee also knew that the information was obtained in breach of a duty.

In 2012, a decision by the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit in SEC v. Obus arguably expanded tippee/tipper liability to encompass cases where neither the tipper nor the tippee has actual knowledge that the inside information was disclosed in breach of a duty of confidentiality.3 Rather, a tipper's liability could flow from recklessly disregarding the nature of the confidential or nonpublic information, and a tippee's liability could arise in cases where the sophisticated investor tippee should have known that the information may have been disclosed in violation of a duty of confidentiality.4 It is unclear what impact Obus may have on future insider trading cases. At least one district court judge interpreting Obus already curtailed the holding by finding that: (1) a tipper's knowledge that the "disclosure of inside information was unauthorized" was sufficient for liability in a misappropriation case; but (2) a tippee must have "knowledge" that "self-dealing occurred" to be liable under the classical case.5

While the interpretation of the scope and applicability of Section 10(b) and Rule 10b-5 to insider trading is evolving, the anti-fraud provisions provide powerful and flexible tools to address efforts to capitalize on material nonpublic information.

Section 14(e) of the Exchange Act and Rule 14e-3 also prohibit insider trading in the limited context of tender offers. Rule 14e-3 defines "fraudulent, deceptive, or manipulative" as the purchase or sale of a security by any person with material information about a tender offer that he or she knows or has reason to know is nonpublic and has been acquired directly or indirectly from the tender offeror, the target, or any person acting on their behalf, unless the information and its source are publicly disclosed before the trade.6 Under Rule 14e-3, liability attaches regardless of a preexisting relationship of trust and confidence. Rule 14e-3 creates a "parity of information" rule in the context of a tender offer. Any person - not just insiders - with material information about a tender offer must either refrain from trading or publicly disclose the information.

While most insider trading cases involve the purchase or sale of equity instruments (such as common stock or call or put options) or debt instruments (such as bonds), civil or criminal sanctions apply to insider trading in connection with any "securities." What constitutes a security is not always clear, especially in the context of novel financial products. At least with respect to security-based swap agreements, Congress has made clear that they are covered under anti-fraud statutes applying to securities.7

The consequences of being found liable for insider trading can be severe. Individuals convicted of criminal insider trading can face up to 20 years imprisonment per violation, criminal forfeiture, and fines of up to $5,000,000 or twice the gain from the offense. A successful civil action by the SEC may lead to disgorgement of profits and a penalty not to exceed the greater of $1,000,000, or three times the amount of the profit gained or loss avoided. In addition, individuals can be barred from serving as an officer or director of a public company, acting as a broker or investment adviser, or in the case of licensed professionals, such as attorneys and accountants, from serving in their professional capacity before the SEC.

Section 20A of the Exchange Act gives contemporaneous traders a private right of action against anyone trading while in possession of material nonpublic information.8 Although Section 20A gives an express cause of action for insider trading, the limited application and recovery afforded under the statute make Section 20A an unpopular choice for private litigants. Rather, most private securities claims for insider trading are brought under the implied rights of action found in Sections 10(b) and 14(e) and Rules 10b-5 and 14e-3, respectively.

2012 Enforcement activity

In 2012, the SEC filed 55 insider trading actions, and DOJ brought criminal charges involving insider trading against 31 individuals. Remarkably, although the government continued to expend great resources on trials and appeals, enforcement activity in 2012 not only kept pace but surpassed 2011's numbers. The combined total of civil and criminal cases brought in 2012 increased approximately 11% from 2011.

While the SEC and DOJ have been criticized, fairly or not, for not bringing more cases arising from the financial crisis - especially against individuals - both agencies have received abundant praise for their crackdown on insider trading. Insider trading cases, when compared to the sprawling financial crisis investigations, tend to be easier to investigate and easier to explain to a jury. While there has been public outcry to find the villains of the financial crisis and hold them accountable, the government has had a difficult time pinning the blame on one particular person or institution given the unprecedented circumstances that so many (including the government itself) failed to predict. On the other hand, in insider trading cases, the government has had unparalleled success in holding individuals accountable.

As has been the case for the last several years, insider trading cases in 2012 were notable for their size, both in terms of the sprawling webs involved and the outsized profits alleged. Just as it appeared the cases spawning from "Operation Perfect Hedge"9 - a nationwide insider trading investigation of a size not seen since the days of Ivan Boesky and Dennis Levine - were coming to an end, at the end of 2012, the government announced the filing of what it termed the largest insider trading case ever, alleging trading profits and losses avoided totalling more than $270 million.

Galleon Update

We pick up the Galleon story where we left off last year. Raj Rajaratnam continued to press his appeal before the Second Circuit and now awaits a ruling, while national attention turned to the trial of Rajat Gupta, the former chief executive of McKinsey & Co. and former board member of Goldman Sachs and Procter & Gamble, who was indicted in late 2011.

Rajaratna m Appeal Presses On

Following Raj Rajaratnam's conviction - and 11-year sentence - on fourteen counts of securities fraud and conspiracy last year, the former hedge fund mogul began 2012 by continuing his fight against the government's use of wiretap evidence. Rajaratnam must fight his conviction from jail as, in December 2011, the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit denied his request to remain free on bail while the court considers arguments on whether to overturn his conviction.

As we reported in both of our last two Reviews, Rajaratnam had moved to suppress wiretap evidence in the criminal case against him based on his contentions that the government (i) was not entitled to use wiretaps to investigate insider trading because it is not a crime specified in Title III; (ii) failed to establish probable cause or necessity in its wiretap applications; and (iii) failed to minimize monitoring of the conversations recorded.10 Judge Holwell summarily rejected Rajaratnam's suppression motion, finding that although the affidavits in support of the government's applications contained some misstatements, namely the government's failure to disclose an ongoing SEC investigation, the district court still had sufficient facts to find probable cause.11 Ultimately, more than 45 wiretapped conversations were played at Rajaratnam's trial.

The wiretap evidence critical to Rajaratnam's prosecution is now central to his appeal. In briefs filed with the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit early in 2012, Rajaratnam again attacked the validity of the 2008 wiretap order on various grounds, including DOJ's failure to disclose the ongoing SEC investigation into Galleon Group.12 Rajaratnam argued that misleading statements in the government's wiretap application made it impossible for the court to find either probable cause or necessity of the wiretap before authorizing prosecutors to intercept and record phone conversations of Rajaratnam and others. He went on to urge that Judge Holwell's after-the-fact determination that probable cause for the wiretap existed could not save the faulty application relied on in the first instance.13

The Second Circuit heard oral argument on Rajaratnam's appeal on October 25, 2012. During the argument, Rajaratnam's lawyer contended that the lack of disclosure of the parallel civil investigation was a "reckless disregard for the truth" and the affidavit supporting the wiretap application had "cascading errors, paragraph after paragraph after paragraph."14 For the most part, the three appellate judges provided little insight during the argument into their thinking on the case. While they did not ask the prosecutor any questions revealing skepticism of the government's application, they also permitted Rajaratnam's lawyer to argue for double her allotted time.

If the appeal is successful, it will have far-reaching implications for the sprawling web of Galleonrelated insider trading trials of the past two years, all of which derived from wiretap evidence. If Rajaratnam's conviction is vacated because of a tainted wiretap, the government may be forced to retry not only the Rajaratnam case, but also possibly the related cases against Zvi Goffer and Rajat Gupta, all without its powerful wiretap evidence.15

The Gupta Saga

With Rajaratnam's criminal conviction winding its way through the appellate process, attention turned to Rajat Gupta. Late in 2011, DOJ indicted Gupta on charges of conspiracy and securities fraud, thereby ensnaring the most well-known corporate executive to date into Operation Perfect Hedge and confirming that he was the man widely speculated to be the government's "big fish."16

The Gupta trial was particularly noteworthy because the government's case against Gupta lacked two key elements of its case against Rajaratnam: (i) there were no wiretapped conversations directly involving or explicitly mentioning Gupta; and (ii) the government could not point to any tangible benefit to Gupta from his participation in the alleged conspiracy.

Early in 2012, Gupta followed Rajaratnam's lead in seeking to exclude four wiretapped conversations the government sought to use against him at trial. He pressed the same arguments for suppression before Judge Rakoff that Rajaratnam had made before Judge Holwell, and met with the same result: Judge Rakoff allowed the government's wiretap evidence.17

Absent any recordings of Gupta himself, at trial the government offered conversations between Rajaratnam and others to support its theory that Gupta breached his fiduciary duties and passed material inside information regarding Goldman Sachs to his friend, Rajaratnam.18 To take one example, the government played a recording of an October 2008 conversation between Rajaratnam and a Galleon trader in which Rajaratnam said, "I heard yesterday from somebody who's on the board of Goldman Sachs that they are going to lose $2 per share."19

Gupta's lawyers also sought to sow doubt based on the lack of any direct recordings or explicit mention of Gupta, suggesting there may have been another Goldman Sachs insider connected to Rajaratnam who could have been the source of the Goldman information.20 Gupta's lawyers sought to introduce purported recordings of the other Goldman executive passing tips to Rajaratnam, but the taperecorded conversations were excluded by Judge Rakoff as inadmissible hearsay.21 Unable to offer evidence to support its theory of an alternative tipper, the defense could not capitalize on the lack of Gupta's own voice on tape-recorded conversations. Gupta's defense also highlighted the government's inability to show that Gupta received any tangible benefit from passing tips on to Rajaratnam.

The defense focused heavily on the fact that the government's case was vastly circumstantial. For example, the government did not introduce any direct evidence that Gupta tipped Rajaratnam about Warren Buffett's $5 billion investment in Goldman Sachs. Rather than presenting recordings, the government presented the record that Gupta had participated in a Goldman Sachs Board meeting on September 23, 2008, where Buffett's upcoming investment was discussed. That same afternoon, Gupta made a call to Rajaratnam that ended at approximately 3:55 pm. There is no record of what was said between Gupta and Rajaratnam on that call. Before the market closed that day - and before Goldman Sachs made the announcement of the Buffett investment - Rajaratnam purchased approximately $40 million worth of Goldman Sachs stock. At trial, Rajaratnam's assistant testified that on September 23, 2008 Rajaratnam did not receive any calls on his personal line between 3:00 pm and 4:00 pm other than Gupta's call. At summation, Gupta's lawyer emphasized the lack of concrete evidence: "With all the power and majesty of the United States government, they found no real, hard, direct evidence. . . . As they say in that old commercial, where's the beef in this case?"22

The defense, however, was not able to overcome the strong circumstantial evidence presented to the jury and, on June 15, 2012, Gupta was convicted of one count of conspiracy to commit securities fraud and three counts of securities fraud.23 The government's successful prosecution of Gupta despite the lack of direct evidence may serve to embolden future prosecutions. However, the defense efforts were not entirely in vain and likely contributed to Gupta's relatively light sentence and reasonable prospects on appeal.

Following Gupta's conviction, the government requested a Guidelines sentence of 78 to 97 months imprisonment. At the other end of the spectrum, Gupta asked that he be sentenced to no prison time and instead be required to perform community service in Rwanda.24 In sentencing Gupta, Judge Rakoff sharply criticized the result dictated by the Guidelines, noting the "bizarre" result of assigning only two points to Gupta based on his abuse of a position of trust, which was, as the court put it, "the very heart of his offense." By contrast, Judge Rakoff noted that the Guidelines assigned Gupta no less than 18 points based on the "unpredictable monetary gains made by others, from which Mr. Gupta did not in any direct sense receive one penny," suggesting that Gupta's arguments about his lack of benefit did not fall on deaf ears.25

Judge Rakoff was also swayed by Gupta's argument that he had "selflessly devoted a huge amount of time and effort to a very wide variety of socially beneficial activities" and that he did so "without fanfare or selfpromotion."26 The Guidelines sentence, Judge Rakoff ruled, did not "adequately square" with the facts of Gupta's case. Taking into consideration Gupta's personal circumstances and other sentencing factors under 18 U.S.C. § 3553, Judge Rakoff ultimately sentenced Gupta to 24 months imprisonment, a short sentence compared to others from the Galleon web who have gone to trial.

Following his conviction and sentence, Gupta sought bail pending appeal, which the district court denied. In a surprising turn of events, the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit reversed the district court's denial of bail, allowing Gupta to remain free while he appeals his conviction.27 The Court of Appeals' order signals that Gupta has raised non-frivolous issues on appeal that could warrant vacating his conviction. In addition to Gupta's challenge to the government's use of the Rajaratnam wiretaps against him, he also intends to argue that Judge Rakoff improperly excluded wiretap evidence purportedly pointing to an alternate Goldman tipper, as well as evidence that Gupta and Rajaratnam had a falling out shortly before Gupta allegedly tipped Rajaratnam.28

The SEC's parallel case against Gupta is still pending. The SEC is looking to impose a $15 million penalty on Gupta. Meanwhile, to end 2012, Rajaratnam entered into a consent agreement with the SEC to resolve the SEC's case against him for the Gupta-related trades. Rajaratnam agreed to pay $1.45 million.29

Gupta's appeal of his criminal conviction will be expedited and, together with Rajaratnam's pending appeal, places the insider trading spotlight firmly on the Second Circuit as we enter 2013.

Cooperators Sentenced

Throughout 2012, a large cohort of the cooperating witnesses in bringing down Rajaratnam and Gupta was sentenced. Of the eight Galleon-related cooperators sentenced this year, all avoided prison sentences. Michael Cardillo, a former Galleon trader who pleaded guilty to one count of conspiracy and one count of securities fraud, faced up to 20 years' imprisonment.30 But Cardillo provided cooperation that the government called "extraordinary in terms of its extensive impact, in terms of its breadth and scope, in terms of its timing, in terms of its direct result in convictions of multiple individuals, and in terms of his testimony during two of the most high-profile trials in insider trading cases in history," namely the Gupta and Goffer trials.31 For this cooperation, Cardillo received three years' probation, but not a day in jail.32

Likewise, Adam Smith, David Slaine, Rajiv Goel, Anthony Scolaro, Anil Kumar, and Franz Tudor - who were sentenced by five different district court judges - all received sentences of probation for their efforts to assist the government.33 Only Gautham Shankar received more, when Judge Sullivan sentenced him to six months' home confinement.34 As the Galleon tale winds down, one thing is clear: cooperators were rewarded handsomely.

Expert Network Cases

As we noted in last year's Review, by the end of 2011, the government had charged 18 individuals in the expert network cases - two of whom were convicted after jury trials, while the remaining 16 entered guilty pleas. 2012 showed no sign of abatement in the government's aggressive pursuit against the illegal use of expert networks.

The year started off with predawn arrests on January 17 of four individuals from hedge funds associated with the expert network cases: Diamondback Capital Management LP, Whittier Trust Co., and Sigma Capital Management, a division of SAC Capital Advisors LP. The same day the government also unsealed charges against three other individuals. Five of the seven individuals have since entered guilty pleas and the two that fought and went to trial, Anthony Chiasson and Todd Newman, were convicted exactly 11 months after the date of their arrests. Also in December, Diamondback Capital Management announced it would close after investors sought redemptions of $250 million in capital.

In 2012, the expert network cases were not contained to the "circle of friends" of the seven defendants mentioned above. Throughout the year, additional and unrelated individuals entered guilty pleas to insider trading charges involving expert networks. For example, last summer, Tai Nguyen, the president and sole employee of Insight Research LLC, entered a guilty plea admitting that he provided confidential earnings information regarding biotech company Abraxis Inc. to two hedge fund managers - both of whom had already entered pleas of guilty to insider trading in 2011. Likewise, John Kinnucan, founder of Broadband Research LLC and an outspoken thorn in the side of the FBI and DOJ,35 pled guilty to conspiracy and securities fraud charges based on his having passed on to clients material nonpublic information he had obtained from employees of publicly traded companies.

And then, just as it appeared the existing expert network cases were winding down, in November the U.S. Attorney's Office for the Southern District of New York and the SEC announced the filing of what they termed the largest insider trading case ever against Mathew Martoma, a portfolio manager at CR Intrinsic Investors, LLC, an affiliate of SAC Capital. The government alleges that Martoma met Dr. Sidney Gilman through Gerson Lehrman, one of the first and most well established expert network firms. According to the allegations, Dr. Gilman provided Martoma with inside information about disappointing clinical trial results for an Alzheimer's drug being jointly tested by pharmaceutical companies Elan Corporation and Wyeth. The government alleges that Martoma liquidated his fund's long positions in Elan and Wyeth before the clinical trial results became public and which caused both stocks to tumble. As a result, the government contends that the trading profits and losses avoided totaled over $276 million. Martoma has asserted his innocence and has vowed to fight the government's charges. Dr. Gilman entered into a nonprosecution agreement with DOJ and is alleged to be cooperating with the regulators. The government's desire to develop a case against Martoma's former boss Steve Cohen, the head of SAC Capital, perhaps explains the unusual step of granting a total pass to Dr. Gilman, the tipper of the alleged nonpublic information and therefore the but-for cause of any alleged subsequent misconduct.

Appeals and Trials

On Appeal From 2011 Trials

The two defendants in the expert network cases who went to trial and were convicted in 2011 filed appeals in 2012.

As we reported last year, Winifred Jiau, a former Primary Global Research LLC consultant, was the first defendant to be convicted of insider trading in connection with the expert network investigations. Jiau was convicted quickly by a jury after hearing ample evidence, including the testimony from Noah Freeman, a former portfolio manager at SAC Capital Advisors, who himself entered a plea of guilty to insider trading. Freeman testified that Jiau tipped him about results and trends at chipmakers Marvell Technology and Nvidia Corp. During the trial, Freeman testified that Jiau "provided us with almost the complete financial results before they were announced."36 In return, Freeman and other hedge fund managers paid Jiau more than $200,000 and gave her restaurant gift certificates, iPhones, and a dozen lobsters.

Judge Rakoff sentenced Jiau to four years in prison and ordered her to begin her sentence immediately. Jiau made a number of pro se motions before Judge Rakoff, including asking that she be freed while her appeal is pending. Judge Rakoff rejected Jiau's request and said he would no longer accept legal requests by Jiau without a lawyer's assistance. Judge Rakoff denied her request for bail pending appeal, noting that "[n]one of Jiau's other contentions are sufficiently likely to result in reversal, a new trial or a reduced sentence."37 Since Judge Rakoff's denial, Jiau filed a pro se brief in support of her appeal alleging that her counsel did not adequately represent her at trial and that her sentence is disproportionate to those given to others convicted of insider trading.

In the second trial in 2011, James Fleishman, a former sales executive at Primary Global, was also convicted of insider trading within hours of the case being turned over to the jury. The case against Fleishman was unique in that Fleishman was a salesman recruiting clients for Primary Global, but he was not directly involved in working with the experts. Therefore, it seemed it would be harder for the government to establish that Fleishman was privy to misappropriated information. At trial, the government relied heavily on cooperating witnesses, such as Mark Anthony Longoria, a consultant for Primary Global who testified that he provided material nonpublic information to Fleishman's customers. The government alleged that Fleishman deliberately connected the insider with his customers knowing that the insider would provide the improper information. Fleishman was sentenced to 2.5 years in prison.

In his appeal, Fleishman argued, among other issues, that the jury was not properly instructed that the guilty pleas by several testifying cooperating witnesses (who were allegedly part of the scheme in which Fleishman participated) should not have been considered substantive evidence of Fleishman's own guilt. Fleishman further contended that Judge Rakoff should have permitted him to introduce evidence that he had been approached by the FBI and offered a cooperation deal, but he turned it down because he felt he was innocent. The government countered that Fleishman's lawyers failed to object timely to Judge Rakoff's jury instructions as they were given. In January 2013, the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit heard Fleishman's arguments and affirmed the district court's final judgment of conviction.

Perfect Trial Record Continues

Given the tremendous success the U.S. Attorney's Office for the Southern District of New York has recently had in prosecuting insider trading cases, each successive guilty verdict no longer seems newsworthy. However, the convictions of Chiasson and Newman are noteworthy in that the government relied mostly on "old fashioned" evidence at the trial. Unlike the other recent insider trading cases, the government did not have recordings of the defendants. Without wiretap evidence, the government relied heavily on cooperating witnesses.

Also notable is that, while the government called the two defendants members of a "close knit criminal club,"38 at trial there was no evidence of direct dealings between the two of them. Rather, the government was able to obtain a conviction against the two defendants on charges of conspiracy based on the wider interconnected web of tippers and recipients who passed along material nonpublic information. As a result of having been found to be part of a larger conspiracy, Chiasson's gains and losses avoided may be attributable to Newman and viceversa, even if one is unaware of the other's trading activity. As such, Newman may be liable for Chiasson's gains - which were much larger than his own.

Newman and Chiasson are to be sentenced by Judge Sullivan sometime this year. It is widely expected that both defendants will appeal their convictions. As they did in front of Judge Sullivan in their unsuccessful motions for separate trials, we expect one of the issues on appeal to be based on the argument that the evidence did not show that they were part of a single purported conspiracy.

What to Expect Next

As we noted in last year's Review, in connection with the Fleishman case, the government represented that it was still sifting through evidence - including wiretap information on at least 50 hedge funds. In 2012, the government delivered on its promise by bringing new cases, but the level of enforcement activity did not involve 50 hedge funds. The question remains, what else is out there?

The inclusion of "Portfolio Manager A" - widely understood to be Steve Cohen - in the Martoma criminal complaint may have been a signal from the government about the focus of its efforts. To date, neither. Cohen nor SAC Capital has been charged with any wrongdoing related to insider trading. SAC Capital has publicly disclosed that it received a Wells Notice from the SEC in November related to insider trading. It remains to be seen whether anything will come of the government's pursuit of Cohen.

What Does Cooperation Buy You?

Cooperation. The word is filled with meaning for enforcement professionals. SEC and DOJ profess to weigh it heavily when making charging and sanctioning decisions. Courts claim to balance it carefully when making sentencing decisions. But does cooperating really yield tangible benefits for insider trading defendants? Or does it make sense to "roll the dice" and go to trial? Unsurprisingly, the answer is highly fact-specific. But, our analysis of insider trading cases in 2012 and earlier years provides interesting information that may inform the calculus.

What Does It Mean to Cooperate ?

This is an important gatekeeper question. Despite detailed frameworks for evaluating cooperation, the SEC and DOJ have provided precious few specifics for insider trading defendants. The SEC engages in a four-part analysis to gauge an individual's cooperation, but at the time of an investigation a potential defendant can control only a single prong: the assistance provided.39 Here, the SEC factors in both the value and the nature of the cooperation, considering issues like the timeliness and voluntariness of the cooperation and the benefits to the SEC of the cooperation. DOJ likewise may weigh an individual's cooperation when making charging and sentencing recommendations.40 The Guidelines, akin to the SEC's policies, also focus on the timeliness and comprehensiveness of the defendant's assistance.41

Timely cooperation is difficult to provide in an insider trading matter. Investigations frequently begin mere days (if not hours) after the suspicious trading, often without potential defendants being any the wiser. Absent advance self-reporting of insider trading, timeliness thus may best be gauged from the moment of first contact by the authorities. One case filed in September 2012 demonstrates this redefined timeliness. In that matter, the SEC credited Kenneth F. Wrangell with "promptly offer[ing] significant cooperation."42 When contacted about his trading in October and November 2010 (the SEC does not identify when the contact occurred), Mr. Wrangell "provided truthful details acknowledging his own trading and entered into a cooperation agreement that resulted in direct evidence being quickly developed against" two other defendants. The other defendants consisted of a company insider who told his friend and business associate about an impending merger of the company, who then told his golfing partner Mr. Wrangell. But this sort of complete capitulation "at the outset of the investigation" seems to be an anomaly.

Most defendants, therefore, likely may find that their cooperation is most significantly gauged by the value and comprehensiveness of the assistance that they provide. No cooperator to date appears to rival David Slaine in this area. Slaine, who first began cooperating with the FBI in mid- 2007, wired up and recorded several of his own conversations with Craig Drimal, which themselves uncovered the Zvi Goffer insider trading network. Slaine's taped conversations with Drimal and involving Goffer were the basis for the Rajaratnam wiretap warrant application. Slaine therefore was credited with securing wiretapped conversations of Rajaratnam. Slaine also received credit for bringing in additional cooperators, including Gautham Shankar and Thomas Hardin.43 In support of Slaine's bid for a lenient sentence in early 2012, Assistant U.S. Attorneys Andrew Fish and Reed Brodsky called this cooperation "nothing short of extraordinary."44

Entities can cooperate as well. Diamondback Capital Management, for example, settled with both the SEC and DOJ one week after charges were announced.45 Diamondback secured a non-prosecution agreement with DOJ based on, among other things, its "prompt and voluntary cooperation upon becoming aware of the government's investigation," its voluntary implementation of remedial measures, and provision of a "detailed Statement of Facts to the U.S. Attorney's Office setting forth the wrongful conduct of two of its employees." As part of its settlements, Diamondback also agreed to disgorge $6 million, and paid a penalty of one-half that amount. The SEC praised the firm's substantial assistance, "including conducting extensive interviews of staff, reviewing voluminous communications, analyzing complex trading patterns to determine suspicious trading activity, and presenting the results of its internal investigation to federal investigators." Notably, however, Diamondback's pact with the SEC does not include typical language indicating that the firm "neither admits nor denies" any wrongdoing-a result of the SEC's change in policy when settling with defendants involved in parallel criminal matters. And yet, cooperation was not sufficient to save Diamondback from having to shut its doors last year.

What Do Defendants Get From Cooperating ?

The possible benefits for early or significantly helpful cooperation are twofold: a reduced (or no) prison sentence and/or a reduced fine/penalty.

Prison (Or Supervised Release) Happens

In many instances, cooperating may provide a "get out of jail" card. For his extraordinary cooperation, for example, Mr. Slaine was sentenced in 2012 to probation and no prison time. More broadly, a review of sentences over the last three years reveals that cooperators routinely receive supervised release rather than prison. Of the 20 cooperators sentenced in the last three years, 16 of them received no prison time, and only two cooperators received prison time of more than two years.

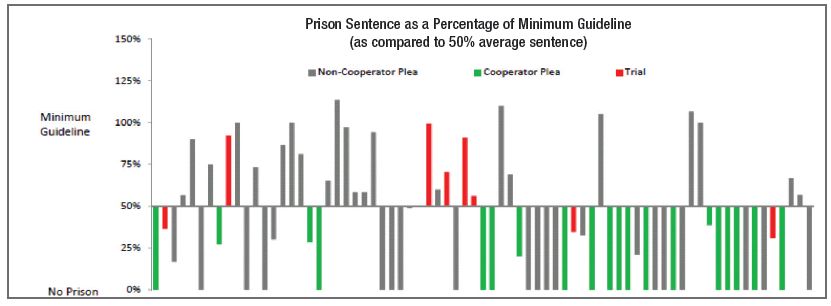

On average, cooperating insider trading defendants received a sentence of around six month - only 26% of the average prison term imposed after plea bargains from non-cooperating defendants (22 months) and a mere 11% of the sentences imposed on defendants who went to trial (56 months). Moreover, cooperators received lower sentences than others who entered pleas even though they faced notably higher sentencing guidelines. In fact, non-cooperating plea bargaining defendants met with the longest sentences relative to their sentencing guidelines. Specifically, cooperators received an average sentence equal to only approximately 12% of the minimum recommended by the Guidelines. In contrast, noncooperating plea bargaining defendants received sentences equal to 73% of the minimum guideline, and defendants who went to trial received average sentences equal to 62% of the minimum guidelines. The graph in the middle of the page illustrates these dramatic benefits to cooperators as compared to the lack of any clear benefit from other pleas.

While there were several large insider trading cases and highprofile defendants over the past three years, they do not skew the averages or conclusions to be drawn. The chart at the bottom of the page illustrates the extent to which each insider trading sentence from 2010-2012 deviated from the average sentence (which was half the minimum guideline).46 We clearly see for cooperators (in green) the consistently belowaverage sentences typically involving no prison time. Also, non-cooperators achieve mixed results, the range of outcomes is much wider, for better and worse, among those who enter pleas than it is among those who go to trial.

Footnotes

1 Chiarella v. United States, 445 U.S. 222 (1980).

2 United States v. O'Hagan, 521 U.S. 642 (1997).

3 See SEC v. Obus, 693 F.3d 276 (2d Cir. Sept. 6, 2012).

4 Id.

5 United States v. Whitman, 2012 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 163138, at *18-20 (S.D.N.Y. Nov. 14, 2012).

6 17 C.F.R. § 240.14e-3.

7 Commodity Futures Modernization Act of 2000, Pub. L. No. 106-554, § 1(a)(5), 114 Stat. 2763 (Dec. 21, 2000) (codified at 15 U.S.C. § 78j(b)).

8 15 U.S.C. § 78u-1.

9 Patricia Hurtado, "FBI Pulls Off 'Perfect Hedge' to Nab New Insider Trading Class," Bloomberg, Dec. 20, 2011, available at http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2011- 12-20/fbi-pulls-off-perfect-hedge-to-nabnew- insider-trading-class.html .

10 Memorandum and Opinion at 1, United States v. Rajaratnam, No. 09-cr-1184 (RJH) (S.D.N.Y. Nov. 29, 2010), ECF No. 148.

11 Id. at 30.

12 Brief of Appellant Raj Rajaratnam, United States v. Rajaratnam, No. 11-4416-cr (2d. Cir. Jan. 25, 2012), ECF No. 75.

13 Id. at 30.

14 Peter Lattman, "Lawyer Denounces Wiretaps in Appeal of Galleon Case," N.Y. Times DealBook, Oct. 25, 2012, available at http://dealbook.nytimescom/2012/10/25/rajaratnams-lawyersargue- to-overturn-conviction .

15 Id.

16 Shira Ovide, "In Arresting Goldman Sachs Ex-Director, Is the Government Chasing the Big Fish?," Wall St. J. Deal J., Apr. 16, 2011, available at http://blogs.wsj.com/deals/2011/10/26/inarresting-goldman-sachs-ex-director-isthe-government-chasing-the-big-fish/.

17 Memorandum Order, United States v. Gupta, No. 11-cr-907 (JSR) (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 27, 2012), ECF No. 42.

18 Indictment ¶ 31, United States v. Gupta, No. 11-cr-907 (JSR) (S.D.N.Y. Oct. 25, 2011), ECF No. 1.

19 Peter Lattman, "Former Goldman Director Gupta to Stay Free Pending Appeal," N.Y. Times DealBook, Dec. 4, 2012, available at http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2012/12/04/formergoldman- director-gupta-to-stay-freepending- his-appeal/ .

20 Patricia Hurtado & David Glovin, "Gupta Seeks Identity of Possible Tipper 'X' at Goldman, P&G," Bloomberg, Jan 28, 2012, available at http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-01-27/gupta-seeksidentity-of-possible-tipper-x-.html ; "Rajat Gupta Defense Rests in U.S. Insider- Trading Trial," June 12, 2012, available at http://www.businessweek.com/news/2012-06-12/rajat-gupta-defenserests-in-u-dot-s-dot-insider-trading-trial .

21 Id.

22 Azam Ahmed & Peter Lattman, "Prosecutors Draw 'Secret Pipeline' Pattern; Defense Asks, 'Where's the Beef?,'" N.Y. Times DealBook (June 13, 2012), available at http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2012/06/13/prosecutorsdraw-secret-pipeline-pattern-defenseasks-wheres-the-beef .

23 Sentencing Memorandum and Order, United States v. Gupta, No. 11-cr-907 (JSR) (S.D.N.Y. Oct. 24, 2012), ECF No. 127.

24 Sentencing Memorandum of Rajat K. Gupta, United States v. Gupta, No. 11-cr-907 (JSR) (S.D.N.Y. Oct. 17, 2012), ECF No. 123.

25 Order, supra note 23 at 2.

26 Order, supra note 23 at 10.

27 Alison Frankel, "Will Rajat Gupta Get off? 2nd Circuit Bail Ruling Offers Clues," Thomson Reuters News and Insight, Dec. 7, 2012, available at" http://newsandinsight.thomsonreuters.com/New_York/News/2012/12_-_December/ Will_Rajat_Gupta_get_off__2nd_Circuit_bail_ruling_offers_clues/" .

28 See Motion for Stay of January 8, 2013 Surrender Date and for Release Pending Appeal, United States v. Gupta, No. 12- 4448 (2d Cir. Nov. 13, 2012), ECF No. 16.

29 Final Consent Judgment as to Raj Rajaratnam, SEC v. Rajaratnam, No. 11-cv-07566 (JSR) (S.D.N.Y. Dec. 26, 2012), ECF No. 59.

30 Government's Letter Pursuant to 5K1.1 at 1, United States v. Cardillo, No. 11 Cr. 78 (JSR) (S.D.N.Y. Oct. 18, 2012), ECF No. 11-1.

31 Id. at 12.

32 See United States v. Cardillo, No. 11-cr-0078 (JSR) (S.D.N.Y. Oct. 18, 2012), ECF No. 13.

33 See United States v. Smith, No. 11-cr- 0079 (JSR) (S.D.N.Y. July 13, 2012), ECF No. 12; United States v. Slaine, No. 09-cr-1222 (RJS) (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 9, 2012), ECF No. 15; United States v. Goel, No. 10-cr-0090 (BSJ) (S.D.N.Y. Oct. 2, 2012), ECF No. 53; United States v. Scolaro, No. 11-cr-0429 (WHP) (S.D.N.Y. Aug. 14, 2012), ECF No. 16; United States v. Kumar, No. 10-cr-0013 (DC) (S.D.N.Y. July 20, 2012), ECF No. 50; United States v. Tudor, No. 09-cr-1057 (RJS) (S.D.N.Y. June 4, 2012), ECF No. 22.

34 United States v. Shankar, No. 09-cr-0996 (RJS) (S.D.N.Y. Apr. 19, 2012), ECF No. 27.

35 See Associated Press, "Analyst Who Taunted Authorities Pleads Guilty," N.Y. Times, Jul. 25, 2012, available at http://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/26/ business/john-kinnucan-pleads-guilty-toinsider-trading.html .

36 Jonathan Stempel, "Ex-SAC manager calls Jiau's stock tips 'perfect,'" Reuters, June 6, 2011, available at http://www. reuters.com/article/2011/06/06/ us-insidertrading-jiau-trialidUSTRE7556Y620110606 .

37 Order at 3, United States v. Jiau, No. 11-cr-00161 (JSR) (S.D.N.Y. Aug. 7, 2012), ECF No. 159.

38 Press Release, U.S. Att'y's Off., S.D.N.Y., Statement Of Manhattan U.S. Attorney Preet Bharara On The Convictions Of Todd Newman And Anthony Chiasson (Dec. 17, 2012), available at http://www.justice.gov/usao/nys/pressreleases/December12/ChiassonNeumanVerdict.php .

39 See SEC Enforcement Manual at § 6.1.1 (Nov. 1, 2012), available at http://www.sec.gov/divisions/enforce/ enforcementmanual.pdf . The SEC also considers the importance of the underlying matter, society's interest in holding the individual accountable, and the personal and professional profile of the individual (including the individual's history of lawfulness, degree of acceptance of responsibility, and opportunity to commit future violations).

40 See United States Attorney's Manual at 9-27.230,9-27.740, available at http://www.justice.gov/usao/eousa/foia_reading_ room/usam/title9/27mcrm.htm#9-27.600 .

41 See United States Sentencing Guidelines Manual at § 5K1.1, United States Sentencing Commission (Nov. 1, 2012), available at http://www.ussc.gov/guidelines/2012_Guidelines/Manual_ PDF/Chapter_5.pdf .

42 See Press Release, SEC, SEC Charges Three in North Carolina With Insider Trading (Sept. 20, 2012), available at http://www.sec.gov/news/ press/2012/2012-193.htm .

43 See Government's Sentencing Memorandum at 6, United States v. Slaine, No. 09-cr-01222 (RJS) (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 9, 2012), ECF No. 13.

44 Id. at 4.

45 Press Release, U.S. Att'y's Off., S.D.N.Y., Manhattan U.S. Attorney Announces Agreement with Diamondback Capital Management, LLC to Pay $6 Million to Resolve Insider Trading Investigation (Jan. 23, 2012), available at http://www.justice.gov/usao/nys/pressreleases/ January12/diamondbacknpa.html ; Press Release, SEC, Diamondback Capital Agrees to Settle SEC Insider Trading Charges (Jan. 23, 2012), available at http://www.sec.gov/news/ press/2012/2012-16.htm .

46 One non-cooperating plea was excluded from this chart because the 6-month prison term could not be expressed as a percentage of the minimum guideline of 0 months.

To view this article in full together with its remaining footnotes please click here.

Because of the generality of this update, the information provided herein may not be applicable in all situations and should not be acted upon without specific legal advice based on particular situations.

© Morrison & Foerster LLP. All rights reserved