We can't recall another new year beginning with such negative sentiment and low expectations for the domestic economy as 2023, with the lone exception of 2009 during the global financial crisis. A mild U.S. recession beginning later in 2023 is now the consensus expectation while inflation remains well above the Fed's target despite seven rate hikes to date and the highest interest rates in 15 years.1

The housing market is poised for a painful year of contraction and falling prices as ultra-low mortgage rates have become a distant memory. More Fed rate hikes are coming in 2023, though fewer and smaller. The only silver lining is that corporate earnings have held up reasonably well through 3Q22, but EPS estimates for 2023 are getting trimmed weekly. Such widespread pessimism makes it tempting to be contrarian here and assume that the negativity baked into economic and market expectations is overdone and won't fully materialize. Perhaps, but don't bet the rent money on that scenario, as there is much that can go wrong in 2023. For the restructuring profession, 2023 is set up to be a strong year for corporate distress and reorganization whether a recession materializes or not, though to what degree is debatable.

The war in Ukraine rages on with little prospect of resolution in sight and has devolved into a proxy war between Russia and NATO nations, primarily the United States, and the war's wider economic impacts and geopolitical fallout in 2023 remain unknowable. High inflation remains problematic globally, while COVID variants unlikely to kill us continue to linger and impede economic growth in much of the world.

Domestically, the Fed has said repeatedly that quelling inflation remains its top policy priority, and that battle is far from done. Its actions to date have probably caused inflation to peak and certainly have helped deflate various market excesses that were prevalent across the economy prior to 2022. For all the bloodletting in financial markets last year, who would argue that such a pullback wasn't long overdue?

However, with labor markets and spending still too strong and little sign that the economy has cooled sufficiently, there is more pain to come from the Fed. Many households will find themselves caught in the crossfire this year, with inflation ebbing but still too high just as a slowing economy starts to hit the labor market and unemployment ticking higher. Corporate layoff announcements have picked up in the last month.2 Be assured that within a few months the Fed will be under mounting pressure from markets, politicians, and other policy shapers to pause or reverse course as inflation eases but remains unacceptably high while the cumulative effects of tight money policies begin to grind on the economy and hurt corporate performance. One prominent hedge fund manager has already suggested that the Fed should raise its 2% inflation target to 3% or slightly higher3, apparently finding it preferable to live with more inflation permanently than endure a corrective bout of economic weakness or contraction. Most advocates of Fed policy-easing in 2023 will be arguing on behalf of their investment portfolios. The greatest determinant of how the year ahead breaks is likely to be whether the Fed stays the course in its inflation fight or yields to market forces clamoring against more tight money and efforts to reduce credit markets' dependence on extraordinary Fed support.

Arguably, the Fed Has Blinked Before

There is recent precedent for the Fed to consider financial market impacts in making policy decisions. It was four years ago this month that the Fed essentially abandoned its intentions to normalize monetary policy after years of unprecedented monetary stimulation following the 2008 global financial crisis. A series of small hikes (25 basis points) to its targeted Fed Funds rate from late 2016 through 2018 brought the target rate up to 2.5% from nearly zero in 2009 through 2015. Such measured moves to gradually restore monetary normalcy were too much to bear for financial markets, with the S&P 500 selling off by nearly 20% from September 2018 through Christmas Day 2018, while the 10-year U.S. Treasury note yield jumped to 3.2% in late 2018 from a low of 1.4% in 2016. Then-President Trump frequently criticized Fed Chair Powell in 2018 for increasing rates at a time when the European continent was awash in negative interest rates for large sovereigns. By late December 2018, the Fed arguably began to accede to these pressures, with the FOMC indicating fewer rate hikes were coming in 2019 than it originally intended.4 Subsequently, Fed rate cuts began in August 2019. In March 2019 the Fed unexpectedly announced that it would be slowing and then ending efforts to shrink its huge balance sheet following a moderate reduction of its securities portfolio in 2016-2018.5 The Fed cited slowing global growth as a reason for its policy reversal — an unusual justification to alter domestic monetary policy at a time when the U.S. economy was relatively robust and outperforming most regions. It sure seemed that market selloffs and presidential jawboning played some role in its decision to reverse course. Consequently, U.S. financial markets went on an absolute tear in 2019 right until COVID-19 struck.

The Fed's efforts to normalize monetary policy would have been abandoned anyway once COVID-19 hit our shores, so the point may seem moot. But its policy reversal in 2019 reinforced the belief among many investors that the "Fed put" was a real thing and that its policy decisions could be influenced by financial market impacts and reactions — a perception forged in 2013 when the Fed decided to postpone its planned taper and phase out of QE stimulus in response to financial markets' infamous "taper tantrum" when it first announced that intent in May 2013.

Again, All Eyes Are on the Fed in 2023

Given the Fed's apparent willingness to consider market impacts and reaction in its policy decisions, its steady determination to implement aggressive monetary tightening actions to slow economic growth caught markets by surprise in 2022 despite the Fed's clear signaling of what was coming, with large rate-hikes and balance sheet reduction continuing uninterrupted since mid-2022. Short-lived market rallies reflected investors' fleeting hopes that the Fed would ease up a bit, but it hasn't to date. How long will it stay the course in 2023?

Ultimately, the Fed doesn't have an entirely free hand in its fight to tame inflation. There is growing recognition that its policy options going forward are handcuffed by the moral hazard effects it encouraged after more than a decade of easy money. In short, cheap and easy money created a barrage of borrowing in recent years by businesses and other private sector entities. U.S. syndicated institutional leveraged loans outstanding now top $1.4 trillion vs. $900 billion in 2017, a nearly 60% increase in just five years, according to Refinitiv LPC6, notwithstanding market share taken by private credit platforms. The ratcheting up of leverage in LBO deals and other aggressive corporate financing actions since mid-decade are mostly attributable to exceedingly low borrowing rates driven by Fed policy decisions.

As credit markets lose Fed support and migrate towards true market-determined rate levels, it's becoming apparent that large swathes of the leveraged corporate sector cannot tolerate high market rates for long and may be unable to service or refinance debt obligations in upcoming years if market rates revert towards pre-2008 historical averages while economic growth sputters. This scenario becomes problematic once we move past 2023, when speculative-grade debt maturities start to become onerous. S&P tallied nearly $900 billion of North American speculative-grade corporate debt outstanding rated B- or worse ("deep junk") in mid-2022, which excludes many billions more in similarly situated unrated debt.

Soon enough, the Fed will feel compelled to ease monetary policy to accommodate profligate borrowers and prevent an ounce of pain from becoming a world of hurt — even if "highish" inflation persists. This path is fraught with potentially negative outcomes, primarily a prolonged resurgence of inflation. Huge borrowing needs of municipalities and the U.S. Treasury will eventually pressure the Fed to intervene actively in credit markets to lower key interest rates and support credit flows and market liquidity, despite its still wildly bloated balance sheet and the inflationary potential of such a move. Like it or not, that die has been cast.

Prospects for Restructuring Activity in 2023

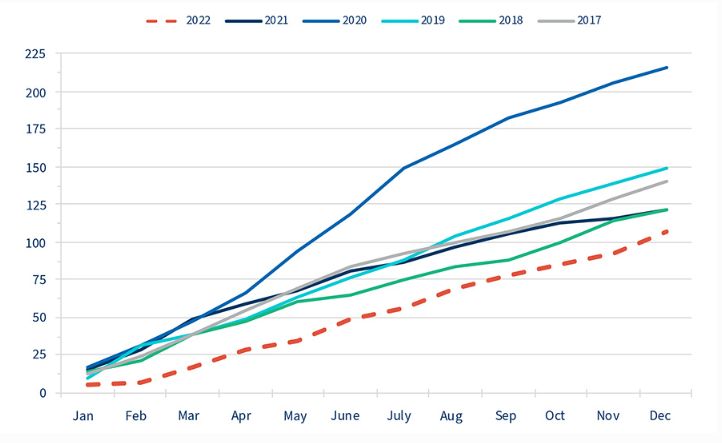

2022 was hardly a standout year restructuring activity, but it ended on a high note with 14 large filings in December, the largest monthly total of the year. Filings in the second half of 2022 easily topped first-half filings, which were hurt by the dismally few filings in 1Q22. However, the year as a whole was not a strong one for restructurings, going strictly by the numbers, with 103 large filings, down nearly 15% vs. 2021, itself a sluggish year (Exhibit 1). The bankruptcy leaderboard reshuffled in 2022, with the healthcare, financial services and real estate/lodging sectors accounting for nearly 40% of all filings. On average, filings were smaller too, with 36% of large filers having liabilities at filing of $50-$100 million, slightly higher than 2021 and well above the 24% average in prior years. At the other end, last year's $1B+ filings matched 2021 with 16, most coming in the second half of 2022.

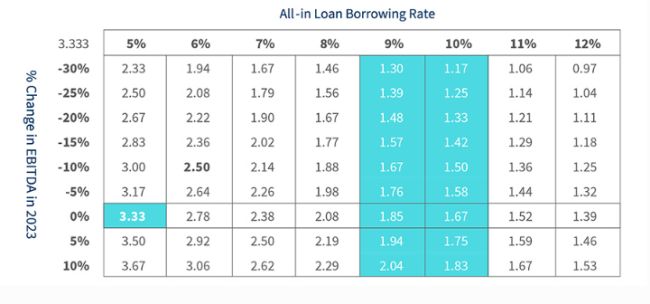

Many restructurings avoided the courthouse, with S&P reporting that 42% of default events in 2022 were distressed debt exchanges7, with many other unrated names also engaging in aggressive liability-management transactions that probably averted a filing. This trend will continue in 2023, as sponsor-owned companies face their most challenging environment since 2009, given the ratcheting up of interest rates and oncoming economic headwinds (Exhibit 2). Expect to see sponsors pull out all the stops to defend investments, especially recent ones, and engage in more debt exchanges, distressed debt buybacks, asset dropdown transactions with unrestricted subsidiaries, non-pro rata capital raises, equity cures and negotiated covenant waivers, with a Chapter 11 filing as a last resort. The ability of sponsors to execute such maneuvers will depend largely on the precise language of the credit documents and the willingness of creditors to take a haircut or commit more capital to a high-risk enterprise. There is nothing pro forma about any of this.

Markets may be underestimating the impact of high interest rates on many leveraged borrowers, which aren't immediately draining on cash flow but take a cumulative toll over several quarters. Base rates for most leveraged loans jumped to 4.50%-4.75% in 2022 — an increase of at least 350 bps for borrowers with LIBOR floors and even more for borrowers without LIBOR floors. This represents a significant spike in borrowing costs, not only for new issuers but all issuers, with all-in yields for most leveraged loans now approaching 10%, in some cases nearly doubling from 2021.

For all the dire concerns from economists and market commentators for 2023, forecasts for defaults and restructuring activity remain surprisingly moderate in the year ahead. The three major rating agencies expect a below-average U.S. spec-grade default rate over the next year or so in the range of 3.5%-4.0% — a sizable jump from the currently depressed default rate of approximately 1.7% but far below historical default rates consistent with a recession and/or default cycle. In fact, S&P's worst-case scenario, which includes a recession outcome, projects a U.S. spec-grade default rate of just 6.0%, far below the peak of previous cyclical downturns.8 Similarly, the distressed debt ratio, a reliable harbinger of future default rates, implies an appreciable uptick in default activity by late 2023 from modest levels but nothing resembling a wave of defaults.

Curiously, credit markets aren't anticipating a surge of restructuring activity in 2023 despite wide expectation of economic malaise and ground-level sentiment among many advisors and counsel that a sizeable buildup of potential restructuring activity has already begun. 2023 is poised to see a steady uptrend in restructuring activity, but it may not be the blowout year that some professionals are expecting. Given the upbeat prospects for our profession in 2023, that's disappointment we can live with.

Exhibit 1 – YTD Cumulative Chapter 11 Filings (Liabilities at Filing > $50 million)

Source: The Deal

Exhibit 2: Interest Coverage Ratio*

* Assumes initial deal leverage (Total Debt-to-EBITDA) of 6X and a 5% borrowing rate in 2021.

Footnotes

1. Ray,Siladitya. "JPMorgan Forecasts 'Mild Recession' In 2023— Here's What Major Financial Institutions Predicted This Week". November 17, 2022. Article.

2. Reuters. "Factbox: Corporate America lays off thousands as recession worries mount. December 22, 2022. Article.

3. Sapienza, Brandon. "Bill Ackman Says Fed's 2% Inflation Target 'No Longer Credible'." December 14, 2022. Article.

4. Transcript of Chairman Powell's Press Conference, December 19, 2018.

5. Transcript of Chair Powell's Press Conference, March 20, 2019.

6. Refinitiv LPC's Leveraged Loan Monthly, November 2022, Slide 47.

7. S&P Global Rating Research, Global Corporate Defaults Push Past 2021's Year-End Total, December 16, 2022.

8. The U.S. Speculative-Grade Corporate Default Rate Could Reach 3.75% By September 2023, S&P Global Ratings, November 21, 2022.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.