As with many issues in our polarized era, there's passionate debate between two rival camps: those who say CEOs are dutybound to speak out, against those who say CEOs are dutybound to stay silent. That puts CEOs, as well as boards, in a bind.

In my professional capacity, I do not align myself with either extreme of the debate. Instead, my advice to boards and CEOs is to consider each situation individually, assessing its unique circumstances, rather than adhering to a rigid doctrine.

I recommend a principled framework that allows each board and CEO to make informed business judgments tailored to their company's specific context, guiding them in deciding when it is appropriate for a CEO to speak out or stay silent on particular issues.

Data and Forces at Work

In the past few years, there has been a lot of research and polling data on CEOs speaking out—sometimes called CEO activism—a new phenomenon unheard of just a decade ago. I will highlight a dozen data points to illustrate the divergent views and practices in this area.

First, a majority of Americans believe that CEOs have a role to play influencing lawmakers—from tax policy to voting rights—although significant minorities do not. That role doesn't necessarily mean speaking out, as Americans are evenly divided over whether CEOs should do that. Political differences appear, with Democrats likelier to support speaking out and Republicans likelier to support staying silent.

Risk cuts both ways, though veers higher for speaking out than staying silent: 89% associate speaking out with some risk while 61% associate staying silent with some risk. Almost no one says speaking out is risk free while 22% think silence is.

These divisions explain why public relations executives spend increasing time discussing whether the CEO should speak out or not. As well as why general counsels are split on the topic—52% support a company policy of the CEO not speaking out while 48% oppose such a policy. 29% of GCs are not even sure whether a CEO speaking out is positive or negative for their company—and those with a view split almost evenly. Amid that division and uncertainty, CEOs appear equally mixed—48% staying silent and 45% speaking out on at least some issue.

Many forces contribute to the pressure on CEOs to speak out. These include structural changes to the corporate landscape: (1) index funds now dominate over stock pickers and are more concerned about general social matters than specific company issues; (2) the Business Roundtable's statement of corporate purpose was expanded to prioritize employees, customers, and communities; and (3) those stakeholders respond with calls to action.

There's been a decline in trust in government, stoked by snafus in its handling of the pandemic, and a rising trust in corporations, especially CEOs. Civic change drive calls for CEOs to speak out, such as (1) the momentum of movements like Black Lives Matter and MeToo, (2) growing climate change awareness and (3) our era's emphasis on personal values among consumers, workers, and investors. To all that, add social media, and the power of its coordinated platforms.

On the other hand, these changes face counterforces, including longstanding duties: (1) CEOs and directors owe fiduciary duties to the corporation and its stockholders; (2) they must put the interests of the corporation and its stockholders above personal beliefs; and (3) they are protected by the business judgment rule, which confers considerable discretion within that framework.

In addition, despite the rising power of stakeholder interests, stockholders elect directors and can sue for breach of duty. Directors are (1) not elected by non-stockholders, (2) don't owe them any special duties, and (3) cannot be sued by them. Public companies must take care that official CEO statements are consistent with applicable securities laws and the company's filed disclosures.

Above all, debates have long raged on the underlying topics, especially corporate purpose and constituencies, offsetting any sense that the world has changed so drastically to warrant new approaches to CEO activism.

The Board's Role

There's even divergence on whether CEOs speaking out is a board issue, though a consensus seems to be emergingthat it is. At least general counsels overwhelmingly believe it is, and for good reasons.

That's not so much because of the hot button topics. Corporations encounter them all the time in the ordinary course, such as employee benefits (from domestic partners to abortion travel expenses) or customer marketing (including branding and spokesperson selections). These are managerial prerogatives, not board issues.

Rather, CEOs speaking out can become a board issue because: (1) its purpose is to draw attention to and support a specific policy position in a public debate, and that directly creates or mitigates a risk, (2) it uses the CEO's public persona outside the ordinary course of business, and (3) the selection and oversight of the CEO is one of the board's most important jobs.

Despite all that, board approaches to this topic vary and are evolving. Research from a board survey shows that 37% of respondents say the company's board has discussed this topic and another 8% were about to; boards are gradually reposing related oversight in various committees, although a significant minority say the CEO is permitted to speak out without board approval; and boards vary in their approach to documenting such oversight, with 31% using a company-specific framework and 30% operating without documentation,

These findings highlight the varying degrees of formal and informal structures that companies are developing. They suggest that there's no one-size-fits-all approach to board oversight of CEOs speaking out.

When considering their role in this complex landscape, directors will appreciate that boards are both legal constructs and social creatures, and attend to both their legal duties and practical realities.

As a matter of law, directors should remember their fundamental commitment to the corporation and its stockholders. This commitment must supersede personal values or the interests of other stakeholders. The legal framework, highlighted by the Delaware Supreme Court in Brehm v. Eisner and elaborated in the Caremark line of cases, emphasizes that directors must determine what is "good," "desirable," or "beneficial" for the company and its stockholders. This determination is grounded in concepts of "good faith" and "reasonableness," not rigid rules or "best practices."

True, the risk to directors of legal liability is slight, as the recent Delaware Chancery Court opinion in Disney makes clear. The business judgment rule, exculpation provisions, and the high hurdle of bad faith see to that. Indeed, the rare cases finding personal liability (such as eBay) are associated with directors repudiating their duty to the corporation and its stockholders. Even so, directors should note the implications of litigation, as the costs of defending even meritless suits can be high, if not in financial terms, then in time, reputation, and electability as a director.

As a practical matter, boards should attempt to align CEO public positions with corporate objectives. This involves a balance between the CEO's influence and the board's oversight responsibilities. The board's role is not to adhere to a specific ideology but to ensure that any company stance is in the best interests of the corporation and its stockholders.

Dynamics between a CEO and the board vary widely based on numerous factors, including personalities, governance structures, industry, and the company's history of public engagement. A cooperative and collaborative relationship between the CEO and the board is generally the most conducive to effective governance. Ideally, boards should empower CEOs to be the voice of the company, while CEOs should seek and value the board's counsel.

On the topic of a CEO speaking out, a board's key role is to help the CEO establish a framework, consistent with its oversight duties, providing guardrails to navigate the issues. Such a framework should be accompanied by regular updates and ongoing dialogue.

A Sample Board-CEO Framework

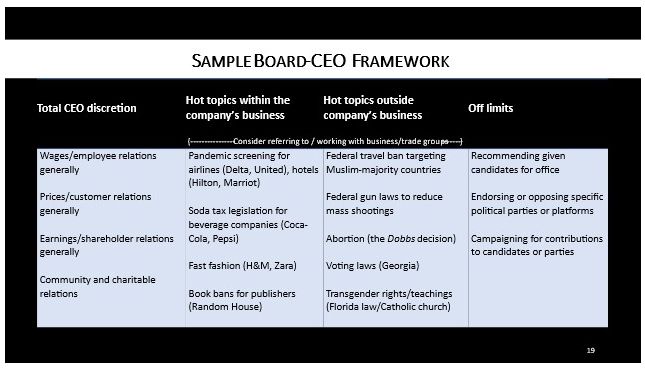

An example of such a framework would put the easiest cases at both ends of the spectrum, with the more contextual in between. In this framework, the CEO would have total discretion concerning public comments on such topics as wages, prices, and earnings, while putting off limits recommending candidates for public office or endorsing or opposing specific political parties, platforms or contributions.

The hot topics in between that pose contextual challenges could be classified according to whether they are within the company's business or not and advise discretion or restraint accordingly.

For example, take public debate over banning books from elementary schools that parents consider inappropriate: that's obviously within the business of publishers, such as Random House, whose board has authorized its CEO to speak out against bans. For most companies, that topic would not be within the company's business, also true of many hot topics, from gun control to transgender issues.

On thorny issues, directors and executives might consider having their company enlist the assistance of business or trade groups with relevant expertise and resources. This option includes withdrawing from them when at odds as Unilever did from the Chamber of Commerce in 2017 and as many large financial institutions did earlier this year, withdrawing from Climate Action 100.

A framework such as this would make clear that a CEO should not have to consult the board on every issue. The framework is a way to set expectations for when consultation is indicated. The approach should be consistent with the standard board model of "nose in, fingers out." Boards should give CEOs ample autonomy, not micromanage, sticking to their roles in oversight not management.

Another advantage and purpose of the framework: the board and CEO must have each other's backs and be united. A CEO out in front of the board may soon face termination. Boards out of line with CEOs face reputational risk and adverse stockholder reactions. The most promising route to such alignment is for all to stress that the company's business is paramount.

Each board and CEO must make judgments to flesh out a framework like this. Given no one-size-fits-all blueprints, boards must rely on management to provide relevant data to inform their decisions.

That said, I can highlight general guidance for boards drawn from the empirical literature. To illustrate a few categories:

When evaluating an issue's relevance to the company, two key factors stand out: first the greatest risks are with commenting on highly polarized issues—those that divide public opinion nearly evenly. The closer an issue is to a 50-50 split in public sentiment, the higher the risk. Second there is lower risk on topics closely related to the business, such as employee benefits.

When considering the CEO's role in public commentary, two factors can mitigate risk: first the CEO's comments should be genuine and true, not seen as a marketing gimmick or strategic ploy. Authenticity resonates positively with stakeholders—even with those who disagree. Second, comments that are consistent with the company's established practices and disclosures tend to carry less risk.

Above all, an understanding of the company's constituents is crucial:

First: consumers often prefer to spend on products that align with their personal values, so it's important to understand these values and assess whether the CEO's comments will align with or contradict them.

Second: Employees generally appreciate it when their CEOs make statements that reflect their own views—and bristle otherwise. Therefore, in organizations with diverse workforces, it is advisable to exercise caution.

Third: the relationship between CEO public comments and investor relations or stockholder returns is complex and research findings are mixed. A good understanding of the stockholder base is essential.

Armed with a framework such as this and the information it calls for, boards and CEOs will be well-positioned to address pressures for CEOs to speak out or stay silent on controversial topics.

Corporate

Purpose and Constituencies

Corporate Purpose Debate

Beyond this practical appeal, the framework has the additional advantage of helping directors cope with underlying debates that fuel this topic, starting with debates over corporate purpose and constituencies. These debates are more than a century old. Despite being shaped by varying socioeconomic contexts of different eras, at bottom they raise identical recurring issues.

In the 1930s, Professors Adolf Berle and Merrick Dodd clashed over whether corporations are economic or social institutions and whether directors should be accountable to stockholders or pursue social objectives. Both views went mainstream, as companies focused on stockholder economic profits while making substantial social and charitable contributions.

In the 1960s and 70s, the debate reignited, as economists like Milton Friedman favored economic profits while critics, led by Ralph Nader, urged "taming" corporations to respond to "public needs." The Naderites won many legislative milestones, from protecting consumers to the environment. But their assaults on corporate America went too far, and an era leaning toward "stockholder value" followed.

In the 1980s, the takeover fights laid bare the tension between stockholder value and other constituencies, such as employees and communities. Directors lobbied to promote the latter, but the law only allowed them to do so if they were rationally related to stockholder interests, which held priority.

In the 1990s, critics again such assailed stockholder primacy as "irresponsible." They advocated diverting corporate assets from stockholders to others, and thus also overshot their mark. Meanwhile, researchers began finding correlations between practices seen as "socially responsible" and corporate financial performance, in categories from employee relations and pollution control to product quality and community involvement.

These dynamics set the stage for ESG principles in 2005, when the United Nations issued them at the New York Stock Exchange, the citadel of stockholder primacy. Unlike predecessors, these ESG principles stress factors that enhance long-term stockholder value, an approach that concurs with history, law, and practicalities. As a result, ESG went mainstream and has influenced investor and corporate behavior.

But ESG faces significant challenges, especially amid increasing politicization of views on corporate purpose. These challenges include:

- definitional ones such as what each element stands for—what are the boundaries or aims of environmental or social or governance principles;

- technical ones such as how to measure, report, and verify ESG performance;

- ethical ones, such as how to balance the interests of different constituents; and

- political ones, such as how to respond to the varying pressures and expectations of different interest groups.

Many boards yearn for a clearer sense of how to respond to this contemporary chapter in this longstanding debate, and the framework should help.

In the polar debate over CEOs speaking out, proponents contend for a social-stakeholder conception of corporate purpose while opponents contend for an economic-stockholder conception.

As such debates have raged for more than a century, however, the truth has always resided somewhere in between—plus ça change, as the French say.

And boards would do better to transcend such debates than to take sides in them. The framework enables doing so.

To illustrate what I mean by the truth residing somewhere in between, I'll conclude by touching on a related debate that periodically flares up, on corporate chartering and corporate law leadership—topics of special interest to this Delaware audience.

Corporate Chartering Debate

Let me frame this topic based on an exchange I had late last year in The Wall Street Journal with former Attorney General William Barr and Washington lawyer Jonathan Berry.

Barr and Berry wrote a column lamenting that Delaware's preeminence in corporate law is under threat. They credit Delaware's leadership to its sensible pro-stockholder jurisprudence. But Barr and Berry caution that Delaware is risking that leadership by "falling in line with ESG to reject shareholder value as corporate law's lodestar."

I wrote a response to Barr and Berry, which the Journal published, respectfully acknowledging the theoretical risk of such a lopsided jurisprudence. But I explained that Delaware remains a stockholder primacy state and that its leadership position is not in jeopardy. In turn, Barr and Berry wrote a reply to me, which the Journal also published. They agreed with my characterization of Delaware corporate law as "the gold standard" but expressed concern that it could be devalued by "cloaking stakeholder politics in the garb of long-term shareholder value."

Why do I think Delaware will continue to be the gold standard in corporate law? Two reasons.

First, Delaware's preeminence in corporate law is partly due to its deliberate pursuit of moderation. The state's approach is built to withstand prevailing political trends in favor of stable corporate principles.

In the legislative realm: the DGCL is crafted by the Delaware State Bar Association, as this room well knows, not the General Assembly. This entrusts the creation of corporate law not to politicians but to a body of experts who dedicate their professional lives to applying, discussing, and advising on those laws.

In the judiciary, the Delaware Constitution requires Delaware's major courts to have a partisan balance. Whatever drawbacks that might have, it promotes a nonpartisan bench focused on business law, not political ideology.

In the executive, even as political leadership changes, participants value the state's reputation for efficient handling of corporate affairs. The infrastructure is a permanent asset, not a partisan one.

These features percolate throughout the legal profession and leadership in Delaware, acting as a buffer against the impacts of political and societal turmoil that afflict other institutions and individuals.

The second reason for my confidence: we've been here before. Throughout all the movements I highlighted in the corporate purpose debates, proponents achieve gains, followed by setbacks and a return to a more centrist position.

Recall the takeover fights of the 1980s, many of which played out here in Delaware. Raiders stressed "stockholder value," while embattled targets lobbied to promote "other constituencies."

The constituencies movement became powerful nationwide. Many states passed "constituency statutes"—although not Delaware. But by ultimately trying to put the interests of such constituents ahead of the rights of stockholders, advocates overplayed their hand and lost the cause.

Amid those battles, the Delaware Supreme Court contributed pivotal, pragmatic clarity, which it and other Delaware courts have repeated ever since. Delaware remains a stockholder primacy state, permitting directors to consider such other interests, but only if those are "rationally related to stockholder interests."

That test was memorably stated and applied by the Delaware Supreme Court back then in its landmark Revlon opinion, a good illustration of Delaware's pursuit of moderation against extremes. That same test was stated and applied by the Chancery Court last June in its opinion in the Disney case involving CEOs speaking out.

Based on Delaware's structure and history, therefore, I believe it will remain the gold standard in corporate law.

Visit us at mayerbrown.com

Mayer Brown is a global services provider comprising associated legal practices that are separate entities, including Mayer Brown LLP (Illinois, USA), Mayer Brown International LLP (England & Wales), Mayer Brown (a Hong Kong partnership) and Tauil & Chequer Advogados (a Brazilian law partnership) and non-legal service providers, which provide consultancy services (collectively, the "Mayer Brown Practices"). The Mayer Brown Practices are established in various jurisdictions and may be a legal person or a partnership. PK Wong & Nair LLC ("PKWN") is the constituent Singapore law practice of our licensed joint law venture in Singapore, Mayer Brown PK Wong & Nair Pte. Ltd. Details of the individual Mayer Brown Practices and PKWN can be found in the Legal Notices section of our website. "Mayer Brown" and the Mayer Brown logo are the trademarks of Mayer Brown.

© Copyright 2024. The Mayer Brown Practices. All rights reserved.

This Mayer Brown article provides information and comments on legal issues and developments of interest. The foregoing is not a comprehensive treatment of the subject matter covered and is not intended to provide legal advice. Readers should seek specific legal advice before taking any action with respect to the matters discussed herein.