INTRODUCTION

Ask parents why they work as hard as they do, and many will answer that it is to give their children a better future. For some, this involves sending their children to foreign countries like the U.S. For others, the hope is to build something they can pass on to their children. But combine the two, and U.S. tax law presents a tricky situation.

Consider Mr. P., a French citizen and resident who is neither a resident nor citizen of the U.S. He starts a business ("OpCo") in the Netherlands in the form of a Dutch B.V. OpCo is owned entirely by HoldCo, Mr. P.'s 100%-owned holding company. HoldCo is a French S.A.S.

Mr. P. sends his only child, Ms. C., to the U.S. for schooling, after which she obtains residence in the U.S., and ultimately gains citizenship. Mr. P. plans for his daughter to inherit HoldCo, which continues to own OpCo. But transferring these entities to a U.S. person creates new challenges. The primary risk is that the transfer can trigger C.F.C. status for both foreign entities.

The Subpart F regime directed at income of C.F.C.'s is designed to prevent U.S. Shareholders benefitting from (i) certain intercompany transactions and (ii) other investment income opportunities offshore. Its companion regime, G.I.L.T.I., is meant to disincentivize U.S. owners of C.F.C.'s from keeping earnings offshore. C.F.C. status is often considered undesirable due to onerous tax and reporting obligations.

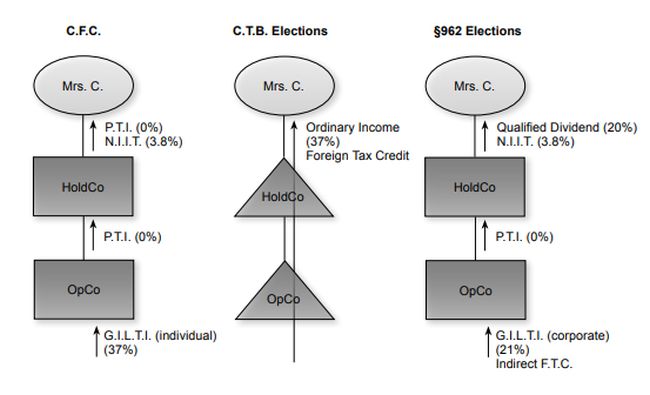

U.S. tax law provides options for mitigating some of these drawbacks. They include check-the-box ("C.T.B.") elections, which allow a C.F.C. to be treated as a flowthrough entity, and Code §962 elections, which allow an individual to be taxed as corporation in connection with income that is taxable under the C.F.C. regimes of U.S. tax law. The benefits are (a) lower tax rates on Subpart F income and tested income under G.I.L.T.I. and (b) access to indirect foreign tax credits while income remains undistributed. The benefit is recaptured when an actual dividend is received from a C.F.C. The previously taxed income benefit is limited to the amount of U.S. corporate tax previously paid under the C.F.C. regimes. As a result, most or all of the dividend retains its character as dividend income received from a foreign corporation. Depending on whether the dividend is a qualified dividend under Code §1(h) (11), it will be taxed as a rate of 20% or 37%.

The following diagram summarizes the basic tax consequences of each option:

CLASSIFICATION OF FOREIGN ENTITIES

The first issue is the status of foreign entities under U.S. tax law. Foreign entities like OpCo and HoldCo that are owned entirely by non-U.S. persons such as Mr. P. and operate outside the U.S. generally do not fall into the U.S. tax net. But a transfer to a U.S. person changes things.

A foreign entity is a C.F.C. if it is a corporation in which "U.S. Shareholders" own more than 50% of the voting power or value of all issued shares outstanding.1 For this purpose, U.S. persons are U.S. Shareholders only if they hold at least 10% of the foreign entity, measured by voting power or value.2 When Ms. C. inherits her father's ownership in HoldCo, she will be a U.S. Shareholder with respect to HoldCo and will own more than 50% of the outstanding shares of HoldCo if the value of the bare legal title exceeds the value of the income interest. In addition, Ms. C is considered an owner of HoldCo's shares in OpCo because U.S. law applies indirect ownership rules and rules under which ownership by one entity or person may be attributed to a U.S. taxpayer for purposes of determining whether that U.S. taxpayer is a U.S. Shareholder and whether the particular foreign corporation is a C.F.C. 3 Those rules will cause OpCo to be a C.F.C. and Ms. C to be its U.S. Shareholder.

OpCo and HoldCo must be corporations under U.S. law for them to be C.F.C.'s. U.S. law classifies a foreign entity based on the number of its shareholders or members entity and the extent of their liability. A foreign entity is a corporation if all shareholders or members have limited liability for the debts and other obligations of the entity.4 The general understanding is that shareholders of a Dutch B.V. or a French S.A.S. are not personally liable for the debts and other obligations of the underlying entity. B.V.'s and S.A.S.'s are therefore corporations for U.S. purposes. This, combined with Ms. C.'s U.S. Shareholder status, means that HoldCo and OpCo will become C.F.C.'s when their shares pass to Ms. C.

The discussion in the foregoing paragraph are addressed to default classifications, meaning that no action is taken to change the classification for income tax purposes in the U.S. A C.T.B. election is available for certain entities, which allow them to change their entity classification for U.S. tax purposes. Foreign entities that are not eligible to change their classifications tend to be limited to those entities that can issue shares that are publicly traded on an exchange. Examples are S.A.'s, P.L.C.'s, A.G.'s, and N.V.'s.5

C.F.C. ISSUES

C.F.C. status results in several unfavorable consequences for U.S. Shareholders. U.S. persons that are shareholders in a foreign corporation that is not a C.F.C. are not taxed on the corporation's earnings until dividends are received.6 For an individual, the tax rate on dividends is capped at 20% when the dividend is a qualified dividend. To be qualified, a dividend must be distributed by a U.S. corporation or a corporation that is eligible for benefits granted under a comprehensive income tax treaty with the U.S.7 In additions, the I.R.S. must determine that the treaty is satisfactory8 and an exchange of information program must be in effect. Finally, the foreign corporation cannot be a P.F.I.C. in the year a dividend is paid or the preceding year and cannot be a surrogate corporation under the anti-inversion rules.9 Individual U.S. shareholders are also subject to net income investment tax ("N.I.I.T."), a 3.8% tax on passive income.10 The I.R.S. position is that N.I.I.T. cannot be offset by a tax treaty or by foreign tax credits.11 The position was upheld by the U.S. Tax Court.12

U.S. Shareholders of a C.F.C. no longer benefit from deferral in a material way. They are taxed on most or all of the earnings of a C.F.C. in the same year as earned by the C.F.C., even if not distributed in the form of a dividend. Income tax is imposed under one of two regimes: Subpart F or G.I.L.T.I. The Subpart F regime applies to (i) certain intercompany transactions between the C.F.C. and a related party13 and (ii) passive income earned by the C.F.C. from financial investments and the like.14 Subject to minor exceptions,15 G.I.L.T.I. applies to most of what is not caught by Subpart F.

Since OpCo earns its income from running a standalone business, its income most likely is covered by the G.I.L.T.I. provisions. When OpCo recognizes income, Ms. C. will treat the income as "tested income" that is included in her income tax return for the same year. She will pay U.S. tax computed at ordinary income rates that top out at 37%. As an individual filing a tax return on Form 1040, she is not entitled to claim a foreign tax credit for Dutch corporate income taxes imposed on OpCo in the absence of an election made in Ms. C's U.S. income tax return to be taxed under the Subpart F and G.I.L.T.I. provisions as if she were a corporation, rather than an individual. This is discussed below.

Alternatively, Ms. C may seek relief under the high tax exception to both C.F.C. provisions if the effective rate of French tax exceeds 90% of the U.S. corporate tax rate. The effective rate of tax is computed by restating the income of OpCo to comply with U.S. tax accounting rules and dividing the actual French tax paid or incurred by the restated net income before foreign income taxes.16 The effective rate of tax must be at least 18.9% in order to claim the benefit of the high tax exception.

If a U.S. Shareholder is taxed on a C.F.C.'s Subpart F income or G.I.L.T.I., dividends to upper-tier entities and eventually to the U.S. Shareholder are considered previously taxed income ("P.T.I.") and are exempt from a second round of income tax.17 Therefore, while HoldCo's dividends from OpCo would ordinarily be Subpart F income to HoldCo and taxed to Ms. C. as such, the P.T.I. rule spares her from a second level of tax. Similarly, and as a general rule, HoldCo's distribution of that income to Ms. C. does not trigger more income tax for her.

In addition to this increased tax burden, U.S. Shareholders face heavy annual reporting obligations. The full extent of these requirements depends on a shareholder's level of ownership and involvement in a C.F.C. Since Ms. C. will become a majority owner, her requirements will be on the heavier side. Acting as an officer or director of HoldCo or OpCo would further increase her reporting burden.

Usufruct Arrangements

A common planning tool in many civil law jurisdictions is a usufruct arrangement, under which ownership rights over a piece of property is divided between an income interest and an ownership interest.18 Broadly, one person, known as the usufructuary, retains the right to the use of the property or the income from the use of the property, while another person holds the bare legal title to the property. A typical arrangement involves a parent, who is a usufructuary, and a child, who is the bare owner, with the child receiving full ownership of the shares at the conclusion of the parent's lifetime. The local tax benefit is a significant reduction in inheritance taxes.

With one exception,19 usufruct arrangements are not commonly available in the U.S. Certainly, tax law provisions that focus on usufruct arrangements are few, if any. 20The I.R.S. sometimes analogizes usufructs to life estates.21 In a life estate, the life tenant enjoys use of a property during his or her lifetime, but the usufructuary may be obligated to preserve the underlying property to a greater or lesser extent, as agreed. At the life tenant's passing, ownership of the property passes to the remainderman. At that point, the life interest and the remainder interest are merged into full tile. The usufructuary corresponds to the life tenant, and bare legal owner corresponds to the holder of the remainder interest.

While usufruct arrangements provide inheritance tax benefits in civil law jurisdictions, the desired benefit is not available under U.S. estate tax rules applicable to U.S. persons planning an estate or for non-U.S. persons owning U.S. situs property. The value of the bare legal ownership at the time of the life tenant's demise is included in the taxable estate where the life tenant owned the property before the remainder interest was given away.22

In addition to issues at the time of inheritance, a usufruct arrangement between a parent resident in a civil law jurisdiction and a child resident in the U.S. brings its own set of issues for the child during the lifetime of the parent. As in our example with Mr. P and his daughter, Ms. C, the arrangement can provide issues for Ms. C where the usufruct relates to shares of stock in a foreign corporation owned by Mr. P. Ms. C's ownership of bare legal title in HoldCo can cause HoldCo and OpCo to be treated as C.F.C.'s. If so, Ms. C is affected by the Subpart F and G.I.L.T.I. regimes. Both companies are C.F.C.'s but the usufructuary, Mr. P, is the only person having an interest in the income of the companies.

In P.L.R. 8748043, the I.R.S. considered whether certain U.S. persons should include Subpart F income in respect of several Dutch controlled foreign corporations ("C.F.C.'s") in which bare legal title was held by bequest. The C.F.C.'s stock was subject to a usufruct created for the benefit of a nonresident alien. The I.R.S. concluded that the corporations were C.F.C.'s, but the U.S. persons were not required to include any Subpart F income. The I.R.S. reasoned as follows:

Since the usufructuary has a 100 percent interest in the income of the corporation . . ., it logically follows that the usufructuary should be treated as the owner of the corporate stock during such time for purposes of subpart F and, by analogy, the foreign personal holding company provisions.

Several years later, Field Service Advice ("F.S.A.") 199952014 looked to P.L.R. 8748043 to reach a similar conclusion regarding the concept of ownership of shares for purposes of Code §958. In a somewhat different context involving a nongrantor trust for which certain persons held life interests and others held remainder interests, the issue presented was whether the remaindermen could be allocated a portion of the Subpart F income of a C.F.C. owned by the trust. The F.S.A. concluded that only the income beneficiaries would be deemed to have an interest in the income of the trust by reason of the application of Code §958.

* * * [W]e conclude that for purposes of section 958(a)(2) and Treas. Reg. [§]1.958-1(c)(2), where a foreign non-grantor trust provides for distribution of all of the trust's net income to one or more named individuals in specified proportions, or (as here), where the trust provides that all its net income should be distributed to a single named individual, the trust's income beneficiaries should be treated as proportionately owning stock owned, or considered as owned, by the trust. Under these circumstances and for this purpose, remainder beneficiaries, whether vested or contingent, should not be taken into account.

Our conclusion supports the purpose of subpart F, which is to avoid the deferral of certain classes of income earned by CFCs by requiring such amounts to be annually included in income by the United States shareholders thereof. Our conclusion also is generally consistent with PLR 8748043 (September 1, 1987), which dealt with the subpart F consequences of an interest in a Netherlands usufruct and * * * concluded that the usufructuary should be considered as owning foreign corporate stock subject to a usufruct interest. The ruling specifically noted that the facts therein supported the conclusion that the usufruct was not an arrangement to decrease artificially a United States person's proportionate interest in the foreign corporation.

Consequently, a usufruct arrangement in which Ms. C holds bare legal title is unlikely to result in an inclusion of income generated by HoldCo and OpCo during the lifetime of Mr. P because she has no right to any income generated by those companies.

The foregoing conclusion may not prevent HoldCo or OpCo from being a C.F.C. for reporting purposes. Depending on the value of Ms. C's bare legal ownership, she may meet the reporting thresholds for filing Form 5471 (Information Return of U.S. Persons With Respect To Certain Foreign Corporations). If she is treated as owning more than 50% of the value of the shares in each foreign corporation, she would be a U.S. Shareholder and the two companies would be C.F.C.'s. Ms. C would have reporting obligations of a Category 4 filer with regard to Form 5471.

In addition to income tax filing, Ms. C may have an F.B.A.R. filing obligation for the financial accounts owned by each of HoldCo and OpCo. Under the F.B.A.R. regulations issued by the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network ("FinCEN"),23 a bureau of the U.S. Treasury Department, each U.S. person having a financial interest in a bank, securities, or other financial account in a foreign country is required to report that financial interest to FinCEN when the aggregate value of all foreign financial accounts exceeds $10,000 at any time during the calendar year. Reporting is effected by filing FinCEN Form 114 (Report of Foreign Bank and Financial Accounts (FBAR)). A U.S. person has a financial interest in a foreign financial account where (i) the owner of record or the holder of legal title is a corporation and (ii) the U.S. person owns directly or indirectly more than 50% of the total value of the shares. If Ms. C. fits within this definition, she may be treated as a holder of a financial interest.

C.T.B. ELECTIONS

Only foreign entities that are corporations are at risk of C.F.C. status. Removing corporate status eliminates C.F.C. status. While this results in the recognition of income by Ms. C on her share of the income and gains recognized by HoldCo and OpCo, two benefits will be realized. The first relates to the period during which Mr. remains alive. As long as income is viewed to be allocated to Mr. P and the allocation has substantial economic effect,24 no income will be realized by Ms. C. The second benefit relates to the period after the conclusion of Mr. P's lifetime. All income and gains that are realized by Ms. C will have the same character in her hands as it would if she received the income directly. To the extent the income consists of qualified dividends and the gains are treated as long-term capital gains, the U.S. Federal income tax will be capped at 20%, plus N.I.I.T.

C.T.B. elections allow U.S. taxpayers to change the U.S. tax treatment of a foreign entity by filing Form 8832 (Entity Classification Election). Checking the box to be a partnership or a disregarded entity means that HoldCo and OpCo will not become C.F.C.'s in the hands of Ms. C. The result is that Ms. C. will be treated as directly realizing HoldCo and OpCo's income when and as realized by those companies. Taxpayers can file C.T.B. elections by submitting Form 8832 to the I.R.S. The effective date of the election can be as early as 75 days before the date of filing the election. The election is made by registered mail addressed to the I.R.S. Service Center, Ogden, UT 84201-0023. If the I.R.S. does not confirm receipt of the election, the instructions advise contacting the I.R.S. Service center with the receipt for the earlier registered mailing.

Timing of C.T.B. Affects Gain Recognition

The timing of the election is important. When a corporation elects to be taxed as a flow-through entity, it is deemed to have been liquidated the day prior to the effective date of the election.25 Its assets are considered distributed to its owner(s), who are deemed to contribute them back to a new flow-through entity.

This deemed liquidation results in gain recognition by the owners as of the day immediately preceding the date of the deemed liquidation.26 In situations like Ms. C.'s, it is generally preferable to have the deemed liquidation take place during the lifetime of the foreign parent. The gain is recognized only for U.S. tax purposes and is taxable only to U.S. tax residents where, as here, all the assets are situated abroad. Having the gain flow through to Mr. P. while he is still the owner means there will be no tax owed on the deemed liquidation, as he is not a U.S. resident. Typically, foreign law will not recognize the liquidation, but that conclusion must be confirmed by competent foreign counsel.

n addition to the immediate potential income tax on any gain resulting from a C.T.B. election, U.S. tax counsel must consider the future U.S. estate tax exposure at the conclusion of Mr. P's lifetime. If Mr. P., OPCO, or HoldCo own U.S-situs assets such as shares in a U.S. corporation at the conclusion of Mr. P's lifetime, those U.S. assets will be will be subject to U.S. estate tax in the absence of an applicable estate tax treaty providind otherwise.27 In determining the base against which U.S. estate tax is imposed, the value of U.S. situs assets can be reduced for a pro rata portion of global expenses, debts, and losses based on the portion of the total value of the worldwide estate that is situated in the U.S.28 In addition, the executor must file a true and accurate U.S. estate tax return that lists all of the gross estate situated outside of the U.S.29

Ordinarily, the estate of a foreign individual is subject to estate tax at graduated rates imposed on U.S. situs assets in excess of $60,000. That exemption is provided by a credit of $13,000 against U.S. estate tax. The tax on the first $1.0 million of a taxable estate is $345,800. Thereafter, a flat 40% tax applies. In these circumstances, tax advisers typically recommend that U.S. assets should be held through a separate foreign corporation. This allows the basis in foreign assets held in a foreign corporation to be stepped up immediately before the date of death. The C.T.B. election for the second foreign corporation owning U.S. assets would be made shortly after the date of death. While the U.S. heir would recognize a pro rata amount of Subpart F income30 or G.I.L.T.I. income arising from the check the box election, in most instances the income tax would be less than the estate tax. Where possible, U.S. situs investment assets should be of a kind that can be rolled over with regularity, thereby limiting the ultimate income tax for the U.S. heir.

However, the rules are somewhat different for Mr. P. Because he is a resident of France, the estate tax treaty between the U.S. and France31 will apply to determine the U.S. estate tax exposure for Mr. P.'s estate. The Estate Tax Treaty provides two main benefits to the estate of a resident of France who owned U.S. situs assets at the conclusion of life.

- The scope of U.S. estate tax is limited to (i) real property in the U.S.,32 (i) business property held through a permanent establishment or a fixed base for providing professional services in the U.S.,33 and (iii) tangible movable property in the U.S.34 All other property is exempt from U.S. estate tax except for French residents who are U.S. citizens or who have their domicile in the U.S.35

- The U.S. will allow a unified credit to the estate of a French decedent on a pro rata basis that looks to the portion of the value of the decedent's worldwide assets that that are situated in the U.S.36

The unified credit is $12.92 million for 2023. The portion of that credit that will be allowed to the estate of Mr. P will be based on the value of U.S. situs assets owned or deemed owned by Mr. P directly or through HoldCo or OpCo once a C.T.B. election is made. Note that while the unified credit increases annually with inflation, it is scheduled to be reduced to an amount that eliminates the tax on $5.0 million in 2026.

Effect of a C-T-B Election on U.S. Heir

Checking the box to treat HoldCo and Opco as flow-through entities can cause substantial changes in the taxation of Ms. C. One key difference is that income is to be taxed as if it flows directly to the owner instead of to a company that is a C.F.C. Both the G.I.L.T.I. and Subpart F provisions result in ordinary income for Ms. C when and as she recognizes income. However, if the income of HoldCo and OpCo arise from qualified dividends or long-term capital gains, the tax rate in the U.S. at the Federal level will be capped at 20%, plus 3.8% N.I.I.T.

In addition, French and Dutch taxes paid by the two companies should be available as a foreign tax credit that reduces U.S. income tax. For an individual, foreign income taxes paid by a foreign corporation reduce earnings, but they cannot be claimed as credits.

CODE §962 ELECTIONS

C.T.B. elections are not the only tax planning alternative in the context of a C.F.C. U.S. tax law provides that an individual who is a U.S. Shareholder with regard to a C.F.C. can make an election to be taxed as a corporation for purposes of computing tax under Subpart F and G.I.L.T.I.37 This is commonly known as a Code §962 election. There are three main consequences to making the election: (i) G.I.L.T.I. is taxed at a lower tax rate, (ii) an indirect foreign tax credit becomes available, and (iii) actual distributions to the U.S. Shareholder become taxable.

Foreign Tax Credit Computation Under G.I.L.T.I.

As a deemed corporate taxpayer under Code §962, Ms. C. pays the corporate rate of 21% on her G.I.L.T.I. inclusion resulting from OpCo's income and is entitled to a 50% deduction,38 effectively cutting her G.I.L.T.I. rate in half to 10.5%. This is preferable to the top graduated rate for an individual, currently set at 37%. When a C.F.C. owned by an individual retains its earnings for use in the business, the rate reduction has a material benefit arising from the lower effective tax rate that is due without the receipt of funds from the C.F.C.

The benefit is enhanced if OpCo pays Dutch tax on its earnings under the indirect foreign tax credit provisions of Subpart F39 and G.I.L.T.I.40

Corporations that are U.S. Shareholders of a C.F.C. may claim an indirect foreign tax credit for foreign taxes paid by that C.F.C. The credit may reduce or eliminate Ms. C.'s U.S. tax under both provision. However, the foreign tax credit benefit in the context of G.I.L.T.I. limited. A corporation that is a U.S. Shareholder can claim a foreign tax credit only for 80% of foreign income taxes paid by a C.F.C. on its tested income.41 As with indirect foreign tax credits under Subpart F, the amount claimed as a foreign tax credit must be grossed-up when computing the G.I.L.T.I. inclusion.42 The increased amount then increases the benefit of the 50% deduction discussed above.

When computing the foreign tax credit limitation, a special basket is provided for G.I.L.T.I. inclusions and the foreign income taxes on those inclusions. Unused foreign tax credits cannot be carried to another year. If not used in the year they arise, they are lost. In comparison, the direct foreign tax credit that is available once a C.T.B. election can be carried back and forward as provided under the rules of Code §904 – one year back and 10 years forward.43

Tax Treatment Upon Receipt of Dividends

A Code §962 election enabling Ms. C to compute tax as a corporation alters the way in which actual distributions are taxed. The dividend from OpCo to HoldCo continues to be treated as P.T.I. if the underlying earnings of OpCo were taxed previously in the hands of Ms. C under Subpart F or G.I.L.T.I. The rules change when a dividend form HoldCo is received by Ms. C. The Code §962 election denies full P.T.I. treatment for the distribution.44 The portion of the dividend that is treated as P.T.I. is limited to the U.S. income tax that was previously paid on Subpart F income or tested income under G.I.L.T.I. While the actual dividend remains foreign source income received from a foreign corporation – which may or may not be a qualified dividend depending on the ability of the foreign corporation to obtain benefits under an income tax treaty – the amount that is taxable reduced, more or less as if the dividend flowed through a U.S. holding company that paid U.S. tax (reduced by allowable foreign tax credits), after which it distributed a dividend to its shareholder.

CONCLUSION

There is no one solution for all taxpayers. A taxpayer seeking a more precise answer must evaluate the paths in order to identify the path that results in the most attractive after-tax position, with the best likelihood of success, at the most reasonable cost to operate.

Footnotes

1. Code §957(a). All references to the Code and. refer to the Internal Revenue Code of 1986 as currently in effect. All references to Treas. Reg refer to associated regulations issued by the I.R.S.

2. Code §951(b).

3. Code §958.

4. Treas. Reg. §301.7701-3(b)(2)(i)(B).

5. For a complete list, see Treas. Reg. §301.7701-2(b)(8).

6. Immediate taxation also arises when a foreign corporation is a P.F.I.C. and a U.S. shareholder makes a Q.E.F. election. This article does not address issues regarding P.F.I.C.'s.

7. Code §1(h)(11).

8. For a list of satisfactory treaties, see Notice 2011-64.

9. For a list of satisfactory treaties, see Notice 2011-64..

10. Code §1411(a)(1).

11. Treas. Reg. §1.1411-1(e).

12. See also Toulouse v. Commr., 157 T.C. 49 (2021).

13. Code §954(d), applicable to foreign base company sales income, and (e), applicable to foreign base company services income.

14. Code §954(c), applicable to foreign personal holding company income.

15. Code §951A(b)(1), applicable to net deemed tangible income return, and (c)(2) (A), applicable to specified income excluded from tested income.

16. Code §954(b)(4); Treas. Reg. §1.954-1(d)(4).

17. Code §959(a).

18. See Fanny Karaman and Stanley C. Ruchelman, "Usufruct, Bare Ownership, and U.S. Estate Tax: an Unlucky Trio," Insights Vol. 3. No. 8, (September 2016), and Fanny Karaman and Beate Erwin, "Basis Planning in the Usufruct and Bare Ownership Context," Insights Vol. 4 No. 3, (March 2017).

19. Louisiana.

20. One example seems to appear in Treas. Reg. §1.1014-2(b)(2).

21. E.g., Rev. Rul. 66-86; P.L.R. 201032021.

22. Code § 2036.

23. 31 C.F.R. § 1010.350.

24. Code §704(b)(2). Treas. Reg. §1.704-1(b)(2).

25. Treas. Reg. §301.7701-3(g)(1)(ii).

26. Treas. Reg. §301.7701-3(g)(3)(i).

27. Code §2511.

28. Code §2106(a)(1).

29. Code §2106(b).

30. Code §951(a)(2)(A).

31. Convention Between the United States of America and the French Republic for the Avoidance of Double Taxation and the Prevention OF Fiscal Evasion With Respect to Taxes on Estates, Inheritances, and Gifts ("the Estate Tax Treaty"). It entered into force on October 1, 1980 and was amended by a protocol that entered into force on December 21, 2006.

32. Article 5 of the Estate Tax Treaty.

33. Id., Article 6.

34. Id., Article 7.

35. Id., Article 8.

36. Paragraph (3)(a) of Article 12 of the Estate Tax Treaty

37. Code §962.

38. Code §250.

39. Code §960(a).

40. Code §960(d).

41. Code §960(d)(1).

42. Code §78.

43. Code §904(c).

44. Treas. Reg. §1.962-3(a).

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.