Forty-three years after the release of Led Zeppelin's famous rock ballad Stairway to Heaven, the Ninth Circuit, sitting en banc, cleared Led Zeppelin of allegations that the opening riff of Stairway infringed the copyright to Spirit's song Taurus.

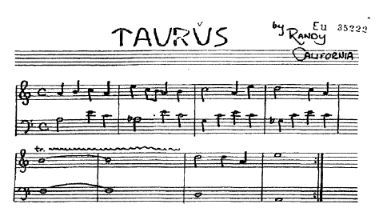

Taurus was written by guitarist Randy Wolfe, a.k.a. Randy California, who was the front man for Spirit until he died in 1997, and the song was registered with the Copyright Office in 1967. But Wolfe did not sue Led Zeppelin for infringing his song while he was alive. And even after Wolfe's death, when the copyright was owned by the Randy Craig Wolfe Trust (established by Wolfe's mother), no infringement suit was brought. Rather, it was not until 2014, eight years after Michael Skidmore became a co-trustee of the Trust, that suit was brought. Skidmore's suit was based on the allegation that the opening notes of Stairway were "substantially similar" to the following "eight-measure passage at the beginning of Taurus":

At trial, the jury found that Stairway to Heaven did not infringe the Taurus copyright, but on appeal, a three-judge panel of the Ninth Circuit vacated part of the decision and remanded the case for a new trial. That decision became short-lived, however, when the Ninth Circuit granted rehearing en banc to decide how courts should apply the "selection and arrangement" rule, under which normally unprotectable elements of a song can be protected if they have been selected and arranged in a particular way.

To decide whether Led Zeppelin infringed the Taurus copyright, the en banc court walked through several significant questions of copyright law.

First, the en banc court confirmed that the 1909 Copyright Act protects only the written composition deposited at the Copyright Office, not the sound recording based on the written composition. So, the relevant portion of the Trust's copyright is the handwritten sheet music pictured above, not the sound recording of Taurus, and it doesn't matter if the songs sound the same.

Second, the court recognized that copying can be proven circumstantially by establishing "access" and "substantial similarity." Skidmore argued that he had proven copying at trial by showing both that Led Zeppelin members had heard Taurus before creating Stairway to Heaven and that Stairway is similar to the Taurus sheet music (that is, that the similarities between the two songs are too compelling to be coincidental).

But to show access, Skidmore had also wanted to play Taurus for Led Zeppelin guitarist (and certified rock god) Jimmy Page, who wrote Stairway to Heaven. Skidmore defended this request by arguing that he hoped to show, through Page's facial reactions, that Page recognized the song from listening to it between 1968, when Taurus was released, and 1970, when Page wrote Stairway. But the trial court didn't want the jury to compare the Taurus recording to Stairway, so it refused. And the en banc court agreed, stating that "[t]here would have been very little, if any, probative value in watching Page's reaction to listening to Taurus at the trial in 2016 to prove access to the song half a century ago." Moreover, the court decided that this issue was moot in any event, since Page admitted in his testimony that he owned the album containing Taurus and the jury found that he had access to Taurus before Stairway was written.

Third, the en banc court considered what is called the "inverse ratio rule," which provides that the required proof of similarity between the copyrighted and allegedly infringing works is lowered when a copyright owner has made a strong showing of access to the copyrighted work. The Ninth Circuit has followed this rule since 1977, but it has been criticized as leading to confusing rulings because the court never explained how to apply it—obviously, no amount of access makes B minor the same as C major. So the en banc court abandoned the rule, and the Ninth Circuit now demands the same showing of similarity regardless of access.

Finally, the en banc court addressed the "selection and arrangement" rule, under which a combination of normally unprotectable elements can be protected. As the court explained, though, this rule does not allow a composer to randomly select a set of unprotectable elements and obtain copyright protection. Rather, it provides protection only where the individual elements were selected and arranged in a "new" or "original" way, and the accused song can be found to infringe only if it shares the same combination of unprotectable elements arranged in the same way.

In the end, though, the en banc court concluded that Skidmore's infringement argument was not based on the selection and arrangement rule, and that he had made only "a garden variety substantial similarity argument." And while the court recognized that there were similarities between Stairway to Heaven and Taurus, it agreed with the district court that they failed to establish infringement. As the court said, "Just as we do not give an author 'a monopoly over the note of B-flat,' descending chromatic scales and arpeggios cannot be copyrighted by any particular composer." The en banc court thus affirmed the district court's conclusion that Stairway does not infringe Taurus's copyright.

The case is Skidmore v. Led Zeppelin, No. 16-56057 (9th Cir. March 9, 2020) (en banc).

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.