The rise of generative artificial intelligence tools have dramatically altered the creative landscape, essentially enabling an amateur hobbyist with access to a computer to produce professional-level and imaginative content.

For example, aspiring time-traveling influencers can now use generative AI to create travelogues that transport their followers to historical moments, complete with selfies in front of under-construction pyramids. And for those looking to break into the world of theater, the advent of Dramatron has paved the way for digital playwrights to craft complex, nuanced stories with the help of AI.

With the ability to create infinitely expanding worlds, game designers can use AI to generate vast landscapes, populate them with characters and creatures, and even generate quests and storylines for players to follow.

This proliferation of generative AI tools has sparked a burgeoning industry AI whisperers dubbed "prompt engineers," who are proficient in crafting prompts that instruct AI models on how to generate text, images and videos.

While these AI tools bring with them not only impressive capabilities to transform content creation, they also give rise to a host of novel legal, regulatory and ethical questions. In this article we will focus on some of the most pressing and complex concerns that will need to be navigated by participants in the creator economy.

Many entertainment businesses including music publishers, game studios and traditional news companies, as well as the creators who contribute to these businesses, are grappling with both how best to use AI tools and how to police their rights with respect to others' use of the same tools.

Who owns AI-generated works?

Ownership of AI-generated works has been a topic of academic debate for years, but has only recently come to the forefront with the increasing prevalence and sophistication of AI technology. Take for example the artist who used Midjourney last year to generate the first place winning entry to the Colorado State Fair.

Who is the owner of that piece of art? Should it be the artist who carefully crafted the prompt that generated the image? Should it be the engineers who developed and authored the code and algorithms powering and supporting Midjourney to take user input and transform it into images?

Should it be the Midjourney AI software itself? What about the creators of the images and photos that trained Midjourney to generate the output? And should that image even be protectable as a copyrightable asset?

Although the Copyright Act does not specify the criteria for what constitutes an author, the U.S. Copyright Office took the position in February that it will not register works produced by a "machine or mere mechanical process that operates randomly or automatically without any creative input or intervention from a human author."

According to the Copyright Office, the crucial question is determining if the creation of a work is primarily the result of human effort, with the use of a computer as just a tool or facilitating instrument, or if the defining aspects of the work - such as storyline and plot, artistic style or musical composition - were actually generated and produced by a machine, and not a human.

Thaler's and Kashtanova's Attempts

For example, the Copyright Office last year rejected Stephen Thaler's attempt to register an AI-generated piece of artwork entitled "A Recent Entrance to Paradise," wherein Thaler argued that the AI-powered system itself, DABUS, was the author. This registration was rejected due to the human authorship requirement.

Digital artist Kris Kashtanova initially registered with the Copyright Office "Zarya of the Dawn," a comic book with imagery generated with the assistance of Midjourney's textto-image AI model.

However, the Copyright Office has since reversed course. It asserted in February that the individual images generated by Midjourney as part of this registration "are not the product of human authorship" and accordingly, are not eligible for copyright protection.

However, the Copyright Office has since reversed course. It asserted in February that the individual images generated by Midjourney as part of this registration "are not the product of human authorship" and accordingly, are not eligible for copyright protection.

According to Kashtanova's lawyer, this process typically involves a level of creativity that can be similar to the craftsmanship recognized by U.S. copyright law in photographers, which interestingly initially faced pushback from the creative community as a mode of artistic expression.

The Copyright Office Guidance

The Copyright Office subsequently issued recent guidance asserting that if the "AI technology is determining the expressive elements of its output, [then] the generated material is not the product of human authorship."

It goes on to state that if a generative AI model creates a visual, written or musical work that is based solely on a prompt received by a human - regardless of the level of creativity exhibited in the prompt - then the resultant work is not eligible for copyright protection.

However, a collection of unregistrable AI-generated works might still be protectable as a compilation, as in the case of Kashtanova's "Zarya of the Dawn," which received limited protection as a compilation even though the Copyright Office deemed that none of the AIgenerated images themselves were eligible for protection.

Additionally, if a human author modifies or edits an unprotectable work - e.g., one in the public domain - the Copyright Office will register that modified or edited work only if it presents a "sufficient amount of original authorship" which would independently be copyrightable.

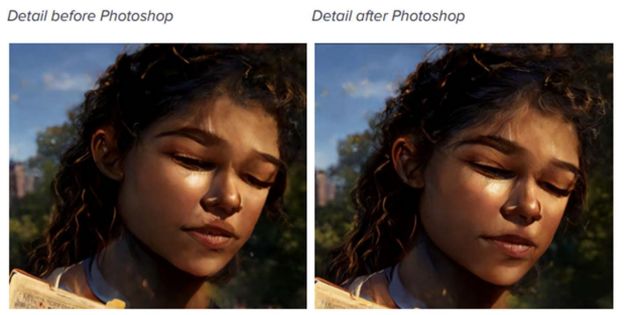

The Copyright Office explained that Kashtanova's digital enhancements to Zarya's lips are "too minor" and "imperceptible," and accordingly do not qualify for copyright protection.

Kashtanova's digital enhancements to Zarya's lips do not qualify for copyright protection.

While the Copyright Office has not yet expressed a clear standard for which modifications or edits to an AI-generated work are entitled to copyright protection, it implied that they should be nontrivial or evoke a different aesthetic appeal. Further activity in this arena will be required in order to determine which elements of an AI-generated work are copyrightable.

According to the U.S. Supreme Court in Feist Publications Inc. v. Rural Telephone Service Co. in 1991, a work must possess "at least some minimal degree of creativity." However, the Copyright Office appears to focus more on whether the user of the generative AI tool could have predicted the expressive output of the tool.

One thing that is clear is that the Copyright Office has taken a staunch stance that human authorship is a requirement for protection, so tools that can detect AI-generated works, such as DetectGPT or DE-FAKE, will likely be of importance in determining registrability.

And failure to properly disclose the use of generative AI tools in the creation of registered content could lead to the registration being canceled, as well as allow a court to disregard the registration in the context of an infringement action, which could impede the author's standing or ability to bring an infringement lawsuit regarding such content.

Rights of Publicity

As AI technology advances with the ability to generate sounds, images and deepfakes that uncannily resemble a natural person, so too does the potential for that content to infringe on such person's rights of publicity - i.e., where an individual has the right to control the exploitation of their identity, including protection of their name, likeness and voice.

These rights of publicity vary across each state, and sometimes include certain postmortem protections as well. For example, California provides 70 years of protection, but only for deceased personalities.

In 2020, New York passed Senate Bill S5959D, which prohibits the use of digital replicas without consent, where such digital replicas may implicate the likeness, either in still image or video, or synthetic voice creations of generative AI systems.

AI-generated content - such as images of Emma Watson reading Adolf Hitler's "Mein Kampf" or Pope Francis wearing a white puffer coat - can be so realistic that it is difficult to distinguish from genuine content, and as a result, individuals may find their likenesses being convincingly used without their consent.

Defenses to Rights of Publicity

Defenses to rights of publicity typically hinge on whether the content falls under a protected form of free speech, and in the commercial context, success in many instances depends on showing sufficient transformative use of a person's likeness.

This can include transforming the purpose of use, such as for parody, satire or commentary, or the likeness itself - such as in 2003 when the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, in ETW Corp. v. Jireh Publishing Inc., invoked transformation as part of its ruling that a painting celebrating Tiger Woods, with several prior winners of the Masters Tournament superimposed in blue and white in the background, did not violate the golfer's right of publicity.

As a baseline, a number of cases - including the 2013 decisions Keller v. Electronic Arts Inc. and Hart v. Electronic Arts Inc. in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit - have determined that simply incorporating a celebrity's publicity rights into a new medium is likely not going to be sufficient to avoid a right of publicity claim.

In the AI context, one can extend this to state that simply using generative AI prompts incorporating name and likeness rights will likely be met with the same fate under right of publicity jurisprudence.

By generalizing the output produced by an AI tool sufficiently so that it does not identify a celebrity, a content creator can reduce risk of violating that celebrity's right of publicity in using that generic output as a character in a video game or other medium.

Such an approach may be analyzed in a similar fashion to the 2018 Lohan v. Take-Two Interactive Software Inc. decision from the New York Court of Appeals

The court indicated that while an avatar in a video game or like media may constitute a portrait within the meaning of N.Y. Civil Rights Law Sections 50 and 51 - with regard to invasion of privacy - the video game character simply was not recognizable as plaintiff, and the defendants did not use the celebrity's name and likeness to refer to plaintiff in the game, and did not use a photograph of her in the game.

Mitigation Steps for Copyright Infringement and Rights of Publicity

Navigating the legal implications of using AI-generated content featuring or incorporating a third party's artwork, music, voice or image will require careful consideration of both the respective rights and defenses of creators, media companies and content platforms.

Celebrities or other rights holders need not only rely on right of publicity or copyright protections, but to the extent they have licensed usage rights to a creator, the rights holder may be better off relying instead on their contractual rights.

It is becoming increasingly common for performers, for example, to include contractual protections against generative AI tools, such as Keanu Reeves, who revealed in a Wired interview in February that he always includes a prohibition on studios digitally modifying his performance, motivated by an instance in which a digital tear was added to his on-set performance.

On the platform side, in light of the potential for misuse of AI-generated content, technology companies offering generative AI tools and platforms are increasingly acknowledging this possibility and taking measures to prevent bad actors from using their AI tools in violation of various laws.

These measures are consistent with take-down principles employed in the past for infringing or other content that violates laws or the platform's user terms or policies. Given the ease with this AI-generated content can be produced, similar to so-called fake news, platforms will ultimately need effective policies related to deterrence, mitigation and takedown strategies.

Various platforms are currently thinking through how to roll out these policies and respond in real time to viral, generated media.

This month, a number of platforms took down the AI track called "Heart on my Sleeve," performed by AI versions of Drake and The Weeknd - which amassed tens of millions of views across TikTok, Spotify, Twitter and YouTube - based on demands of the rights holders, particularly since it raised issues of copyright infringement.

This is an area of active research, with taxonomies developing for mitigation strategies, such as platforms requiring proof of personhood, using widely adopted digital provenance standards and coordinating with AI providers to identify the generated content.

Platforms will need to balance these measures against the immunity they currently enjoy under applicable laws, such as the Digital Millennium Copyright Act Safe Harbors and the Communications Decency Section 230, with respect to user-generated content.

Regulatory Risks and Ethical Concerns

Deception and Job Destruction

While AI technology has revolutionized the creator economy by providing new tools and platforms for content creation and distribution, it also brought about concerns of deception and ethical considerations such as job destruction, as machines and algorithms become capable of performing tasks that were previously done by humans.

For instance, his technology can mimic a podcast host and guest, such as this instance of fake Joe Rogan interviewing fake Steve Jobs.

While generative AI can also be used to bring audiobooks to life, it may pose a threat to professional voice actors that have built careers in narrating those audiobooks. And there continue to be cases of generative AI-related layoffs, such as Sports Illustrated publicly pivoting to AI-generated content.

Regulatory and Judicial Activity

The Federal Trade Commission has also recently weighed in on both the risks of advertising the capabilities of AI tools, as well as omitting disclosure of the use of such tools and using deep fakes or voice clones.

As in other areas of social media content and advertising, disclosure may become a key consideration in the creator economy to balance regulatory and business risks.

Consumers will likely need to know in many instances whether they are viewing human or synthetic content, and content creators may feel that their human-authored works were improperly ingested by the generative AI systems as part of their training, leading to disputes.

In some cases, the public outcry from artists has already led to litigation around these issues, and in other instances, artists have even attempted to goad content owners into litigation against the generative AI vendors, such as using image generators to produce images of Disney characters.

We must wait and see how courts grapple with these issues in order to get clarity on the legal complexities on ownership and infringement of various intellectual property, publicity and privacy rights.

Mitigation Steps

The ethical concerns raised have motivated, at least in part, regulatory and judicial action, which highlights the importance of companies having thoughtful policies and responses to address those concerns.

There might also be technological developments that could mitigate or moot certain concerns, such as tools that make it more difficult to generative AI models to train on your data.

Additionally, developers of the generative AI tools may also create pathways to mitigate those concerns themselves, such as allowing artists to opt out of having their works used as training data, an offer which was taken up by 80 million artists when given the option with regard to the creation of Stable Diffusion 3.

Training may also be limited to public domain or licensed content as we have seen with Adobe's announcement of new design tools, however training on less representative datasets consisting primarily of stock images may lead to impairments in performance, such as Adobe's tools struggling in its generation of images of same-sex couple weddings.

Conclusion

The emergence of AI has brought about significant changes in the creator economy, disrupting conventional workflows and creating fresh opportunities and efficiencies for both creators and consumers.

As AI technology continues to progress and shape the creator economy, it becomes crucial for the entertainment ecosystem to take into account the ethical, legal and regulatory implications, and to keep up to date with the pertinent legal issues such as intellectual property ownership, license rights, rights of publicity and associated liability risks.

Ethical principles based on fairness and notice and explanation have been influential in how regulators are crafting laws, regulations and policies. While traditional content rights holders may not be able to police every use of generative AI, they will undoubtedly incorporate these tools into their own creations and will need internal policies and frameworks to navigate these challenges.

We can expect regulators to provide guidance and enforcement, and for courts to settle certain aspects of disputes, albeit likely at a slower pace than the technology and business adaptations advance.

Originally published by Law360

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.