The holiday season is upon us, and rarely have there been such mixed signals about the health of the consumer economy as we enter this all-important shopping season, with a fair share of Americans doing well but a larger share saying they are struggling. To put some numbers on it, the latest polling data from the University of Michigan (UoM) Surveys of Consumers has 30% of respondents saying they are financially better off than a year ago (vs. 41% last December) and 50% saying they are worse off than a year ago (vs. 32% last December) while 20% say their current financial condition is unchanged.1 This widening gap between the "better offs" and "worse offs" has effectively created two distinct consumer economies with respect to spending patterns and has complicated the task of evaluating current spending trends. The performance of the consumer economy this holiday season will help clarify whether the downbeat sentiment around the economy is justified or exaggerated.

The recent mid-term elections reinforced the notion that we remain a deeply divided nation despite the modest shift in power in Congress and in statehouses, with many races decided by razor-thin margins and both chambers of Congress split nearly equally by political party. But one of the few areas of agreement among most Americans is that they are decidedly unhappy with the state of the economy, though they disagree sharply on the causes of and remedy for this economic condition. That takeaway came across loud and clear in most public opinion polls leading up to and following the election. A Pew Research Center poll in late October indicated that 79% of all registered voters surveyed said that the economy was a "very important" issue in their voting decision, rating it higher than any other voting issue, and especially so among Republican-leaning voters.2 These Pew readings were consistent with other polls taken near the Election Day period.

An overwhelming share of Pew respondents had some negative views on the economy, with 82% saying that economic conditions were either poor (36%) or fair (46%), while just 17% held positive views of the economy compared to 28% earlier in the year.3 Just 9% of Republican respondents rated current economic conditions as either good or excellent vs. 26% for Democratic respondents.4

In brief, the domestic economy is viewed unfavorably by most Americans, as inflation concerns continue to weigh on consumers. Specifically, inflation dominates economic concerns, with more than two-thirds of Pew respondents being "very concerned" about rising prices for various consumer goods.5

In recent years, there is ample evidence that views on the economy are strongly influenced by political affiliation; and that tendency is more pronounced today than ever. However, weakening views on the condition of the economy in 2022 prevail across the political spectrum ― but much more so for Republican-leaning respondents, a possible proxy for the urban/suburban vs. exurban/rural economic divides in the country.

As written previously,6 the UoM's Index of Consumer Sentiment remains near the lows made during the Great Recession of 2009 and far below the worst levels of mid-2020 during the height of COVID-19 shutdowns, even though the domestic economy is on more solid footing today than in either of those perilous episodes. It's hard to reconcile such deeply negative sentiment with facts on the ground, inflation notwithstanding.

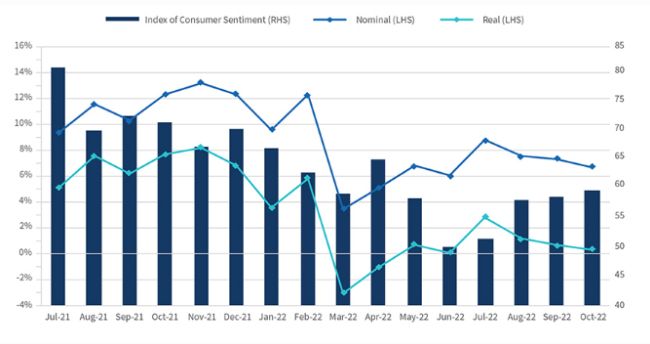

Is it really that bad out there? It depends on where "there" is. Though it may sound out of touch with the financial challenges facing many Americans today, such widespread economic pessimism is confounding given the abundance of economic data and anecdotal evidence that indicate the consumer economy is holding up well, all things considered. More than six months after the Fed began to tighten monetary policy, including an unprecedented four consecutive jumbo hikes of 75 bps each, the U.S. labor market remains tight, with hiring levels still robust, jobs still plentiful, and wage gains still sizeable. Though layoff announcements by some prominent public companies have grabbed headlines lately, overall job creation figures indicate a healthy labor market that has slowed slightly. Moreover, while excess personal savings accumulated during the COVID years are being depleted, they remain ample and should be providing a cushion to help consumers absorb inflation hits. High gasoline prices, a key stress point for cash-strapped households, have eased considerably from early summer, while consumer spending levels remain buoyant. Nominal retail sales growth (YoY) has slowed to a mid-to-high single-digit range, down from unsustainably low double-digit growth between late 2021 and early 2022 (Exhibit 1), hardly a severe pullback given the Fed's persistent efforts to slow the economy.

Anecdotally, one cannot walk the streets of most major cities and reasonably conclude that consumers are holding back, as stores, cafes, bars and restaurants are routinely teeming with patrons. Admittedly, the spending pulse of large urban centers isn't reliably representative of the wider country, but these scenes aren't reflective of the 1% either: a whole lot of people continue to spend freely, judging from the size of crowds and consumer spending data. For many Americans, inflation is mildly troubling but hasn't induced spending cutbacks, with UoM recently reporting that nearly 40% of survey respondents haven't changed their spending habits at all in the face of inflation; and that percentage moves up to nearly 50% for higher income, more educated, and Democratic-leaning cohorts.7 Moreover, the recent runup in credit card debt outstanding amid a time of sharply rising interest rates might indicate that those struggling to make ends meet are putting it on the plastic rather than cutting back. From the street level, it hardly feels like a brewing recession. However, the scene may look different in much of rural America; and such contrasts, though very real, are probably obscured from the view of pundits and TV cameras.

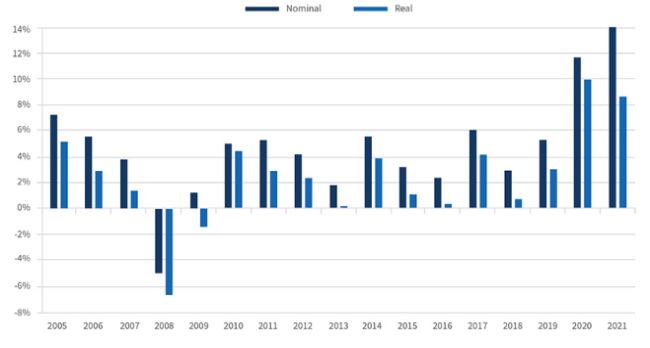

That is the backdrop as we enter this holiday season. Reported 3Q22 sales and earnings to date from several major retailers, including Walmart, Dick's and Best Buy, have exceeded reduced expectations and provide some optimism that this season won't disappoint. Historically, holiday sales growth this century (prior to COVID-19) typically meandered in the low-to-mid single-digit range; but 2020 and 2021 were unprecedented blowout years in which growth topped 11% (Exhibit 2), driven almost entirely by COVID-related factors. Such standout performance won't continue this year, as the financial windfall for many households from the COVID-19 episode has been winding down while high inflation has forced discretionary spending cutbacks among lower- and middle-income households.

Holiday retail sales growth certainly will fall short of 2020-2021, given how anomalous those two years were, and are likely to be in the range of 5.0%-7.0% (YoY). This isn't a forecast; it's an extension of nominal sales trends in recent months (Exhibit 1). Prior to 2020, when annual inflation was consistently around 2.0% for years, such sales growth would have been considered a stellar season — but high inflation has changed the interpretation, and real sales growth would be negligible at such levels. Many retailers are facing the prospect of a holiday season with little real sales growth despite "healthy" topline numbers, as inflation takes a big bite from them as well. Moreover, indications of very aggressive discounting during Black Friday weekend could further compromise gross margins as retailers jostle to get inflation-weary shoppers to bite.

The strength or weakness of this holiday season will certainly inform the Fed's policy decisions going into 2023. Financial markets and retailers may cheer a strong season, but such an outcome would probably compel the Fed to continue with aggressive rate hikes and a "higher for longer" posture. The fundamental quandary facing the Fed currently is whether its tightening policies to date are delayed in taking effect or have been insufficient in slowing the economy and tamping down inflation. Those who advocate for smaller rate hikes or a pause believe that the time lag between action and effect is long, and fear that repeated large rate hikes could derail the economy when their delayed impact finally hits.

A strong holiday season — somewhere above the current trendline — coming on the heels of six months of jumbo rate-hikes and QT asset runoffs would largely undermine the long-time-lag argument and probably induce the Fed to keep its foot firmly on the brake pedal in 2023, though financial markets remain somewhat incredulous that it will do so. So, good news ultimately might be bad news if it's too good, and a middling holiday season might be the best of all outcomes—except for retailers.

Exhibit 1 – Retail Sales Growth (YoY) – Excluding Auto and Gas

Source: U.S. Census Bureau and University of Michigan Surveys of Consumers

Exhibit 2 – U.S. Holiday Retail Sales (YoY% Growth)

Source: U.S. Census Bureau and FTI Consulting analysis

Footnotes

1. Hsu, Joanne. "Surveys of Consumers, University of Michigan". September, 2022. Article.

2. Schaeffer, Katherine & Van Green, Ted. "Key facts about U.S. voter priorities ahead of the 2022 midterm elections". Pew Research Center. November 3, 2022. Article.

3. Ibid

4. Pew Research Center. "Midterm Voting Intentions Are Divided, Economic Gloom Persists". October 20, 2022. Article.

5. Ibid

6. Eisenband, Michael C. "Losing Confidence in Consumer Confidence". FTI Consulting. July 19, 2022. Article.

7. Hsu, Joanne. "Surveys of Consumers, University of Michigan, Five Patterns in Consumer Responses to Inflation". November 18, 2022. Article.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.