Barring any unforeseen, last minute Congressional action, on December 1, 2015, amendments to ten of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure will become effective. The amendment process began five years ago when the Judicial Conference's Advisory Committee on Civil Rules (the "Advisory Committee") explored changes at a May 2010 conference at Duke University School of Law. Over the next three years, the Advisory Committee developed the proposed changes, and an extensive public comment period followed in which more than 2,300 public comments on the proposed changes were submitted. Earlier this year the Supreme Court approved the proposed amendments to Rules 1, 4, 16, 26, 30, 31, 33, 34, 37, and 55.

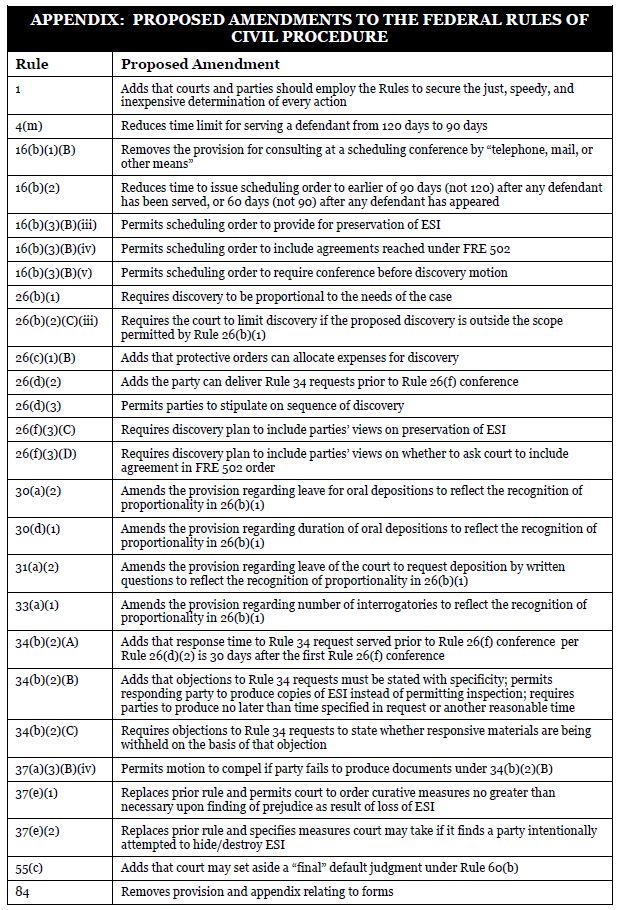

This article focuses on one of the most significant changes to the Federal Rules—the rewriting of Rule 37(e) governing the failure to preserve electronically stored information ("ESI"). We have provided a quick reference guide to all the proposed changes, however, at the end of this article.

CURRENT RULE 37(e) – A "NOT-SO SAFE HARBOR"

Current Rule 37(e) was adopted in 2006 to serve as a "safe harbor" for ESI lost as the result of routine, good-faith practices. It provides:

(e) Failure to Provide Electronically Stored Information. Absent exceptional circumstances, a court may not impose sanctions under these rules on a party for failing to provide electronically stored information lost as a result of the routine, good-faith operation of an electronic information system.1

Although Rule 37(e) seemed to protect innocent parties who merely made a mistake resulting in the loss of ESI, in application, the rule largely did not provide such protection. Despite the seemingly difficult standard to impose sanctions—a court must find "exceptional circumstances"—court-ordered sanctions are not uncommon. For example, courts often award sanctions based on other authority, such as a court's inherent powers.2 In addition, although the existing rule appears to prevent sanctions if a party loses information as a result of negligence, some courts, such as the Second Circuit, have authorized adverse-inference instructions based on a finding of negligence or gross negligence.3 As a result, litigants often preserve much more information than they will ever use in litigation. For example, in 2011, Microsoft reported that for every 2.3 MB of data that is actually used in litigation it preserves 787.5 GB—a ratio of 340,000 to 1.4

In rewriting the entirety of Rule 37(e), the Advisory Committee concluded that the current Rule 37(e), in practice, has rarely provided a "safe harbor" for litigants. The Advisory Committee Notes to the new rule (the "Notes") state that:

[t]his limited rule has not adequately addressed the serious problems resulting from the continued exponential growth in the volume of such information. Federal circuits have established significantly different standards for imposing sanctions or curative measures on parties who fail to preserve electronically stored information. These developments have caused litigants to expend excessive effort and money on preservation in order to avoid the risk of severe sanctions if a court finds they did not do enough.

As a result, the Advisory Committee decided that "the time had come for developing a rules-based approach to preservation and sanctions."5

PROPOSED RULE 37(E) – A SIGNIFICANT CHANGE

Proposed Rule 37(e) (the "New Rule") provides as follows (with deleted language crossed out and added language underlined below):

(e) Failure to Provide Preserve Electronically Stored

Information. Absent exception circumstances, a court may

not impose sanctions under these rules on a party for failing to

provide electronically stored information lost as a result of the

routine, good faith operation of an electronic information system.

If electronically stored information that should have been

preserved in the anticipation or conduct of litigation is lost

because a party failed to take reasonable steps to preserve it, and

it cannot be restored or replaced through additional discovery, the

court:

(1) upon finding prejudice to another party from loss of the information, may order measures no greater than necessary to cure the prejudice; or

(2) only upon finding that the party acted with the intent to deprive another party of the information's use in the litigation may:

(A) presume that the lost information was unfavorable to the party;

(B) instruct the jury that it may or must presume the information was unfavorable to the party; or

(C) dismiss the action or enter a default judgment.6

When Does The New Rule Apply?

It is important to note at the outset when the New Rule applies. First, the New Rule, like the current rule, applies only to ESI. Second, the New Rule applies only when ESI is lost. The Notes make it clear that loss of ESI from one source is often harmless if substitute information can be found elsewhere. The Notes also state that the New Rule does not apply when information is lost before a duty to preserve arises. Third, the New Rule applies only if the lost ESI should have been preserved in the anticipation or conduct of litigation and the party failed to take reasonable steps to preserve it. The Notes recognize that because of the large volumes of ESI usually involved in cases and the many devices that generate such information, perfection in preserving all relevant ESI is often impossible and thus "reasonable steps" to preserve suffice. The New Rule is inapplicable when the loss of ESI occurs despite the party's reasonable steps to preserve.

What If The Lost Information Can Be Restored Or Replaced?

Under the New Rule, if a party fails to take reasonable steps to preserve ESI that should have been preserved and the ESI is lost as a result, the first step is to determine whether the lost information can be restored or replaced through additional discovery. If the ESI is restored or replaced, no further measures under Rule 37 should be taken. The Notes state that efforts to restore or replace lost information through discovery should be proportional to the apparent importance of the lost information to claims or defenses in the litigation. The Notes provide as an example that substantial measures should not be employed to restore or replace information that is marginally relevant or duplicative. Often parties can recover lost information by restoring backup tapes, but the restoration can be very costly and time intensive. The Notes suggest that resort to restoration of backup tapes is not necessary in all circumstances.

Measures Upon Finding Prejudice

The New Rule states that resort to subsection (e)(1)—where upon finding prejudice the court can order measures no greater than necessary to cure the prejudice—should only occur if:

(1) the ESI should have been preserved in the anticipation or conduct of litigation;

(2) a party failed to take reasonable steps to preserve the ESI;

(3) ESI was lost as a result;

(4) the ESI could not be restored or replaced by additional discovery; and

(5) the court finds prejudice to another party from the loss of the ESI.

The Notes state that the New Rule is silent regarding who has the burden of proof in proving or disproving prejudice. The New Rule leaves judges with discretion to determine how best to assess prejudice in particular cases. Once a finding of prejudice is made, then the court can employ measures "no greater than necessary to cure the prejudice." The Notes state that it may be that serious measures are necessary to cure prejudice found by the court, "such as forbidding the party that failed to preserve information from putting on certain evidence, permitting the parties to present evidence and argument to the jury regarding the loss of information, or giving the jury instructions to assist in its evaluation of such evidence or argument." However, the Notes warn that courts must be careful to ensure that any curative measures under subsection (e)(1) do not have the effect of measures that are only permitted under subsection (e)(2).

Sanctions Upon Finding Intent

Subsection (e)(2)—permitting adverse inference instructions and dismissal or default judgment—applies only if the same first four factors under subsection (e)(1) are applicable plus the court finds that the party that lost the ESI acted with the intent to deprive another party of the information's use in the litigation. The Notes admit the curative measures in this section are harsh but that the subsection was designed to provide a uniform standard in federal court for use of these serious measures. The Notes conclude that the better rule for the negligent or grossly negligent loss of ESI is to preserve a broad range of measures to cure prejudice caused by the loss of the ESI and limit the most severe measures to instances of intentional loss or destruction. Subsection (e)(2) does not include a requirement that the court find prejudice to the party deprived of the ESI because the finding of intent can support an inference that the opposing party was prejudiced by the loss of the ESI that would have favored its position. The Notes caution courts in using the measures specified in this subsection and advise that the severe measures should not be used when the ESI lost was relatively unimportant or lesser measures such as those specified in subsection (e)(1) would be sufficient to address the loss.

HOW DO THE CHANGES TO RULE 37(E) IMPACT ME?

The New Rule eliminates some of the uncertainty surrounding potential sanctions in civil litigation due to spoliation. It creates a uniform standard across federal courts regarding when sanctions for spoliation are appropriate. The New Rule should reduce the prevalence of sanctions and give in-house legal departments some comfort that a mere mistake in preservation will not result in draconian sanctions. The New Rule is clearly a step in the right direction and a significant advancement for defendants who often produce large volumes of ESI in civil litigation.

However, the New Rule is not a cure-all for corporations and financial institutions that struggle with numerous preservation obligations. The New Rule does not govern preservation obligations instituted by regulators or pursuant to regulatory investigations. In addition, the new rule still leaves much open to interpretation. What will courts consider "reasonable steps" to preserve information? How broadly will courts view whether a party has been prejudiced? What will a court view as "no greater than necessary to cure the prejudice"? Who has the burden of proving or disproving prejudice? These are all questions that courts will have to decide, which leaves open the possibility of different courts creating different standards—the exact problem the New Rule was drafted to solve.

Footnotes

1 FED R. CIV. P. 37(e).

2 See Nucor Corp. v. Bell, 251 F.R.D. 191, 196 (D.S.C. 2008) ("Assuming arguendo that defendants' conduct would be protected under the safe-harbor provision, Rule 37(e)'s plain language states that it only applies to sanctions imposed under the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (e.g., a sanction made under Rule 37(b) for failing to obey a court order). Thus, the rule is not applicable when the court sanctions a party pursuant to its inherent powers.").

3 See Residential Funding Corp. v. DeGeorge Fin. Corp., 306 F.3d 99, 113 (2d Cir. 2002) ("discovery sanctions, including an adverse inference instruction, may be imposed upon a party that has breached a discovery obligation not only through bad faith or gross negligence, but also through ordinary negligence").

4 Letter from Microsoft to Honorable David G. Campbell, Chair, Advisory Committee on Civil Rules (Aug. 31, 2011), available at http://www.uscourts.gov/file/microsoftpdf.

5 See Committee on Rules of Practice and Procedure June 2013 Agenda Book at 30-31.

6 Proposed FED. R. CIV. P. 37(e).

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.