On 28 January 2019, the European Commission (Commission) published its Report to the Council and the European Parliament on Competition Enforcement in the pharmaceutical Sector (2009-2017) (Report). This takes stock of all the pharma cases that the Commission has pursued at EU level and that national competition authorities have investigated over the past 10 years. It responds to recent concerns raised by the Council and European Parliament that anti-competitive practices of pharmaceutical companies may prevent patients' access to affordable and innovative medicines.

In parallel, the UK Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) has been very active in investigating the pharma sector and currently has some eight ongoing investigations. Some of these investigations are being narrowed but the overall mood music is that authorities regard pharma cases a high priority. This trend is likely to continue for some time yet.

The key takeaways are (i) pharma cases are likely to continue to be of interest to competition authorities (ii) entry restrictions, high price strategies and loss of exclusivity are key areas of concern together with, going forward, the entry of biosimilar competition.

Overview of the enforcement action across Europe

In the Report, the Commission expresses its belief that EU antitrust and merger control rules play a crucial role in ensuring the correct functioning of the pharmaceutical sector in the EU. The Commission emphasises how competition law enforcement complements the various regulatory systems in place within EU member states, by intervening in individual cases against specific market conducts and ensuring that (i) price competition for pharmaceuticals is not artificially reduced or eliminated, and (ii) anti-competitive practices do not restrict innovation in the sector.

Across the period 2009-2017, over 150 investigations were opened by the Commission and EU National Competition Authorities (NCAs) in the pharmaceutical sector, with 29 decisions finding an infringement or accepting binding commitments, and 20 investigations still ongoing. Of the latter, nine are being pursued at the UK level. In the meantime the UK authority has closed one of those cases (MSD/Remicade).

Source: The Report

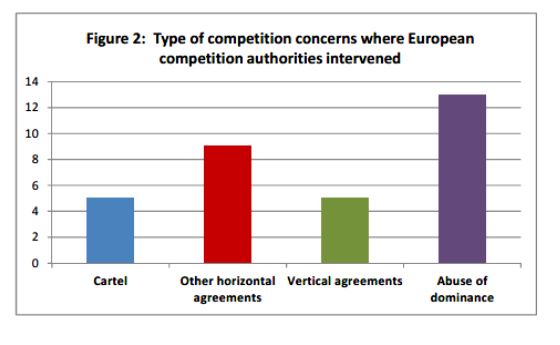

The most widespread types of infringement in the period examined were abuses of dominance, followed by different types of restrictive agreements, such as so called pay-for-delay agreements, outright cartels (such as bid rigging), and vertical agreements (such as exclusivity clauses prohibiting distributors from promoting and selling products of competing manufacturers).

Source: The Report

What are the Commission's main findings?

- Competition from generics and biosimilars1 plays a vital role. The Commission considers the limitation in time of patent rights and other exclusivities in favour of the originator to be fundamental for dynamic competition as this ensures access to cheaper medicines after the end of the exclusivity period. With the increasing cost of medicines, competition from generics and, more recently, biosimilars is, in the Commission's view, a vital source of price competition and a key driver of cost savings for the healthcare system as well as of greater access to medicines for patients. The entry of cheaper generics and biosimilars also generally encourages the originator to continue investing in R&D for pipeline products in order to secure its future revenue streams; as such, competition from generic and biosimilars acts as a disciplining force that compels originator companies to continue innovating. The Commission also believes that competitive pressure from generics may, in some cases, be significantly stronger than competition from other originator medicines as generics contain the same active ingredient, are marketed in the same dosages, and treat the same indications as the originator medicine.

- The Commission views a number of loss of exclusivity strategies as potentially problematic, including:

- Pay-for-delays agreements – whereby, often in the context of patent disputes, the generic company agrees to restrict or delay its independent entry onto the market in exchange for benefits transferred from the originator.2

- Misuse of regulatory framework, such as strategic de-registrations of MAs, misleading representations or other strategies (e.g. application for divisional patents) to extend patent protection.3

- Product denigration and, in general, dissemination of incorrect or misleading information (e.g. on quality and safety of competing generics) in order to curb demand for generics.4

Focus on excessive pricing cases. The Commission notes with approval the adoption of a number of decision condemning excessive pricing both at the EU and national levels.5 In addition, NCAs have also pursued various cases where inflated prices were the (intended) outcome of unlawful coordination among competitors in the form of collusive tenders, price-fixing, restriction on parallel trade and other forms of anti-competitive agreements.6

Insights into UK trends

The CMA regards itself as being at the forefront of competition enforcement in the pharmaceutical sector, with UK cases representing around half of the ongoing pharma cases in the EU.

Some eight UK competition investigations are currently ongoing in the pharma space.

One cluster of cases was opened in 2015/2016 and, as the table below shows, are getting close to a final decision with statements of objections (i.e. draft infringement findings) having been issued to parties. One case (MSD/Remicade) was closed today on the basis of no grounds for action.

A second cluster of cases was opened in late 2017. These cases are still at investigation stage and no decisions have been taken to issue statements of objections. Some of these investigations are being narrowed down as one case has been closed altogether and others are being more narrowly focussed on some molecules.7

Figure 3: CMA investigations in the pharmaceutical sector

The focus of the CMA's investigative action seems to be on entry restrictions and high pricing strategies, although details for approximately half of the ongoing investigations have not been disclosed (yet).

Based on the CMA's timetable, important progress is expected to be made in the first half of 2019, with a decision whether to issue a statement of objections expected to be made in four of the ongoing cases. A final decision was issued only today in Remicade, deciding that, following the statement of objections, there were no grounds for action i.e. the case was closed without an infringement finding.

There are also two CMA decisions currently pending before a Court: the Pfizer-Flynn excessive pricing case currently under appeal before the Court of Appeal, and the Paroxetine reverse payment case currently being examined by the CJEU following a preliminary referral by the Competition Appeal Tribunal (CAT).

It is to be seen what stance the CMA will pursue in the current investigations. The decision by the Court of Appeal in Pfizer Flynn – which follows partial annulment by the CAT of the CMA's findings on the excessive pricing elements of the decision – is long awaited and is likely to influence the CMA's approach going forward, particularly in excessive pricing cases.

What appears foreseeable is that the pharmaceutical industry is likely to remain a focus for the CMA.

Footnotes

1 Biosimilars are biological medicines that – unlike classical medicines – are synthesised from biological, rather than chemical, sources (such as living cells or organisms). As such, they are only highly similar, rather than identical, to the reference medicine.

2 Examples of infringement decisions in pay-for-delay cases include the Commission's decision in case AT.39685 – Fentalyn whereby, by virtue of a co-promotion agreement, Sandoz agreed to refrain from entering the Dutch market with sales of generic fentalyn patch in return for monthly payments calculated to exceed the profits that Sandoz expected to make from selling its generic product. See also the Commission's infringement decision in case AT.3226 – Lundbeck (confirmed by the General Court in 2016 with the decision in case T-472/13) and in case AT.39612 – Perindopril (Servier) (confirmed by the General Court in 2018 with the decision in case T-691/14). At national level, in its Paroxetine 2016 decision, the CMA found that GlaxoSmithKline had induced, through payments and other benefits, three potential competitors to delay their potential independent entry into the paroxetine market in the UK.

3 See, for example, the Commission's decision in case AT.37507 – Generics/AstraZeneca and the 2011 decision by the Office of Fair Trading in the Reckitt Benckiser-Gaviscon case.

4 Judgment in case C-179/16 – Hoffmann-La Roche and Novartis v. Autorità Garante della Concorrenza e del Mercato, where the CJEU considered that an agreement to disseminate misleading information with the aim to reduce off-label use of a competing product may be considered a restriction of competition "by object".

5 Example include the Italian Aspen case – decision by the Italian NCA of 26 July 2017. The case is currently pending, for the rest of the EEA, before the Commission (case AT.40394 – Aspen). See also the investigations opened by the CMA in 2016 against Concordia (Liothyronine tablets) and Actavis UK (Hydrocortisone tablets), respectively. See also the Phenytoin sodium capsules case against Pfizer and Flynn, currently under Appeal with the UK Court of Appeal.

6 Most notably, see the decision by the CJEU in the Hoffmann-La Roche and Novartis v. Autorità Garante della Concorrenza e del mercato, referred to above.

7 In its Q3 report and November 2018 press statement, Concordia announced closure of the CMA investigation into Trazodone and Dicycloverine (as well as Nefopam) on 12 November 2018. In its Q3 report, Concordia refers to ongoing CMA investigations into Nitrofurantoin and Prochlorperazine. On 27 February 2019, Mylan announced that the CMA had closed an antitrust investigation into suspected anticompetitive agreement relating to Nefopam. Aspen confirmed involvement in one of the UK cases in respect of two products: fludrocortisone acetate and dexamethasone.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.