The Senate on July 25 held competing votes on whether and how to extend the tax cuts currently scheduled to expire at the end of 2012, and House Republicans have introduced a separate version for a vote next week. The bills are not expected to lead to an agreement before the November elections, but the differences in the proposals do offer important insight into the outlook for eventual legislation.

The Senate voted on separate proposals from Republicans and Democrats. The Republican alternative (S. 3413) was rejected 45–54 while the Democratic bill (S. 3412) was approved 51–48. Although S. 3412 has now passed the Senate, it is essentially stuck, because the Constitution requires revenue measures to originate in the House. Senate Republicans agreed to simple majority votes on S. 3412 and S. 3413 so senators could record their tax policy preferences and would likely block any attempt to attach the Senate bill to a House revenue measure. House Republicans, however, plan to vote on their bill to extend the tax cuts (H.R. 8) next week and said they will allow Democrats to offer the Senate bill as an amendment. The House is expected to defeat the amendment and pass the Republican bill, with no progress toward a compromise. At this time, the bills in both the House and Senate should be viewed largely as vehicles for members to stake out their positions on the tax cuts in advance of the November elections.

All three bills would extend most of the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts for one year, but the Democratic version would roll back the tax cuts on income exceeding $200,000 for singles and $250,000 for joint filers. The Republican versions would also extend the estate and gift tax rules agreed to in 2010. The Democratic bill does not address the estate tax, but would extend other tax incentives enacted in 2009. All three versions offer alternative minimum tax relief, and none would repeal the new Medicare taxes for 2013 or extend the popular tax provisions that expired at the end of 2011, such as the research credit.

The bills are unlikely to be enacted, but the votes reveal important developments:

- No one is arguing for a long-term bill; all appear to agree on a one-year extension.

- Republicans are not yet linking their efforts to extend the tax cuts through 2013 to efforts to repeal or defer the new Medicare tax in 2013.

- Democrats have not yet reached a consensus on estate and gift taxes.

Income taxes

The tax cuts originally enacted in 2001 and 2003 are scheduled to expire at the end of the year, but currently provide:

- rate cuts across all tax brackets, with a top rate of 35% (down from 39.6%),

- top rates on capital gains and dividends of 15%,

- full repeal of the personal exemption phaseout (PEP) and "Pease" phaseout of itemized deductions,

- zero rate for capital gains and dividends in the bottom brackets,

- marriage penalty relief,

- $1,000 refundable child tax credit, and

- several other benefits, including increased dependent care and adoption credits and enhanced education incentives.

These tax cuts were originally set to expire at the end of 2010, but an agreement late that year extended them through the end 2012. The new House and Senate bills all generally propose to extend the tax cuts for one more year, through 2013, except that the Senate Democratic bill would allow the rate cuts to expire for incomes above certain thresholds.

The income thresholds would be set at $200,000 minus the standard deduction and one personal exemption for singles, $225,000 minus the standard deduction and one personal exemption for heads of household, and $250,000 minus one standard deduction and two personal exemptions for joint filers. Above these thresholds, ordinary income in the top two tax brackets would revert to rates of 36% and 39.6% (up from 33% and 35%). Capital gains and dividends above these thresholds would be subject to a top rate of 20%, and PEP and Pease would be reinstated with phase-ins beginning at these thresholds.

The Democratic plan largely follows President Obama's positions, except on dividends. The president's latest budget calls for letting dividends revert to treatment as ordinary income, with a top rate of 39.6%, although in previous budgets he called for a top rate of 20%.

Estate and gift

The 2010 tax cut agreement created new estate, gift and generation-skipping transfer (GST) tax rules for 2011 and 2012 that generally provide:

- reunification of estate and gift taxes with a 35% rate and $5 million exemption ($5.12 million in 2012 after an adjustment for inflation),

- identical rates and exemptions for GST tax, and

- portability in estate tax exemption amounts between spouses.

If no legislation is enacted, the estate, gift and GST taxes will all revert to the rules in place in 2000, with top rates of 55% and exemptions of just $1 million. The bills from both House and Senate Republicans would extend the current rules for one year, through 2013. Senate Democrats initially included a provision applying the rules in place in 2009 ($3.5 million exemptions and top rate of 45%) to 2013, but backed away after several moderate Democrats in relatively conservative states said they may not support such a reversion.

The final bill that passed the Senate does not include any transfer tax changes, a sign that Democrats are far from unified on how to address the issue.

Alternative minimum tax

The most recent AMT relief expired at the end of 2011. The Senate Democratic bill would provide one year of AMT relief by increasing the exemption levels retroactively for 2012. House and Senate Republicans each propose two years of AMT relief for 2012 and 2013.

Section 179

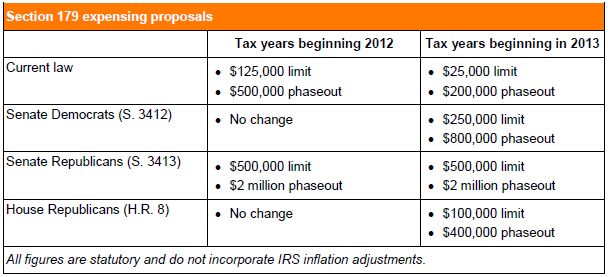

The Section 179 limit is set to revert from $125,000 for tax years beginning in 2012 to just $25,000 in 2013, with the phaseout threshold also dropping. All three bills propose increases in Section 179 allowances for tax years beginning in 2013, and Senate Republicans also propose to retroactively extend the 2010 and 2011 allowances into 2012:

2009 tax incentives

The Democratic proposal would also extend the following proposals that were enacted in 2009 and extended in the 2010 tax cut agreement:

- The American Opportunity Credit for college education

- Enhancements to the earned income tax credit

- Increased refundability for the child tax credit

Neither of the Republican bills would extend these incentives.

Key omissions

None of the bills include proposals to:

- extend popular tax provisions like the research credit, which expired at the end of 2011 and are commonly referred to as "extenders";

- extend 100% bonus depreciation;

- repeal the new Medicare taxes scheduled to become effective in 2013 on income exceeding $200,000 if single or $250,000 if filing jointly; or

- extend the reduced individual Social Security tax rate of 4.2% (down from 6.2%).

Outlook

The three bills are largely campaign exercises and should not be taken too seriously as legislative efforts. Lawmakers are instead expected to launch negotiations in a lame duck session in November, and the outcome will likely hinge on the election. Expired provisions such as the extenders and AMT relief are still expected to be extended retroactively, although there are no guarantees. Despite the political nature of the current votes, those votes do offer clues to what may eventually emerge as a compromise. For one, lawmakers appear to agree nearly unanimously that any extension should be for just one year.

A one-year extension is meant to give lawmakers time and leverage for a potential tax reform effort in 2013. House Republicans plan to offer legislation (H.R. 6169) along with H.R. 8 that would expedite a tax reform bill. The legislation would be required to:

- create just two tax brackets, of 10% and 25%;

- reduce the corporate rate to at least 25%;

- repeal the AMT;

- create revenue estimated at between 18% and 19% of the economy; and

- shift to a more "territorial" tax system.

The president has also unveiled a corporate tax reform plan. Regardless of the outcome of the election, tax reform would be very difficult. A short-term extension of the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts may instead ensure that this legislative process starts all over again very soon.

The votes also reveal that congressional Democrats for now will support proposals to roll back the tax cuts for income above the $200,000 and $250,000 thresholds. Several Democratic lawmakers had previously floated the idea of extending the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts on income up to $1 million. It appears that Democrats are now committed to campaigning on a promise to roll back the tax cuts above the $200,000 and $250,000 thresholds, but there may be room for negotiation in a postelection lame duck session.

It may or may not be significant that Republicans did not attempt to roll back the new Medicare taxes in these votes. The health care legislation enacted in 2010 will increase the individual Medicare tax by 0.9% tax on earned income above $200,000 for singles and $250,000 for joint filers, and impose a new 3.8% tax on investment income above those thresholds. It is scheduled to become effective in 2013, at the same time and at the same basic income level for which Democrats propose to roll back the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts. Although Republicans have called for repealing the health care bill and the Medicare tax (and House Republicans have passed bills to repeal both), Republicans have not rhetorically linked the Medicare tax to the expiration of the other tax cuts. It is not clear whether this could make it more difficult to include a repeal of the Medicare tax in a lame duck compromise on the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts.

Tax professional standards statement

This document supports the marketing of professional services by Grant Thornton LLP. It is not written tax advice directed at the particular facts and circumstances of any person.

Persons interested in the subject of this document should contact Grant Thornton or their tax advisor to discuss the potential application of this subject matter to their particular facts and circumstances. Nothing herein shall be construed as imposing a limitation on any person from disclosing the tax treatment or tax structure of any matter addressed. To the extent this document may be considered written tax advice, in accordance with applicable professional regulations, unless expressly stated otherwise, any written advice contained in, forwarded with, or attached to this document is not intended or written by Grant Thornton LLP to be used, and cannot be used, by any person for the purpose of avoiding any penalties that may be imposed under the Internal Revenue Code.

The information contained herein is general in nature and based on authorities that are subject to change. It is not intended and should not be construed as legal, accounting or tax advice or opinion provided by Grant Thornton LLP to the reader. This material may not be applicable to or suitable for specific circumstances or needs and may require consideration of nontax and other tax factors. Contact Grant Thornton LLP or other tax professionals prior to taking any action based upon this information. Grant Thornton LLP assumes no obligation to inform the reader of any changes in tax laws or other factors that could affect information contained herein. No part of this document may be reproduced, retransmitted or otherwise redistributed in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including by photocopying, facsimile transmission, recording, re-keying or using any information storage and retrieval system without written permission from Grant Thornton LLP.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.