The capital formation environment has significantly changed in the last two decades and, in particular, following the global financial crisis of 2008. The number of initial public offerings has declined, and M&A exits have become a more attractive option for many promising companies. This article reviews trends in the initial public offering market, notable alternatives to IPOs, and follow-on offering activity.

A Changing Environment

While completing an IPO used to be seen as a principal objective of and signifier of success for entrepreneurs—and the venture capital and other institutional investors who financed emerging companies—this is no longer the case. Market structure and regulatory developments have changed capital-raising dynamics following the dot-com bust and financial crisis. At the same time, private capital alternatives also have become more varied and more significant.

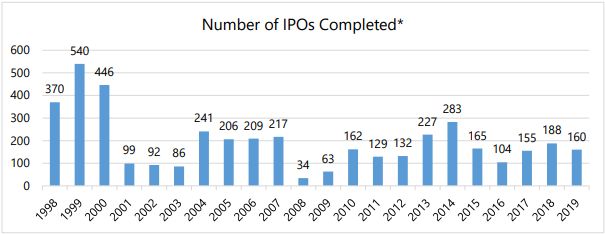

The number of IPOs drastically declined after 2000 compared to prior historic levels. After a brief increase in the number of IPOs following the aftermath of the dotcom bust, the number of IPOs declined again, partly as a result of the financial crisis. Changes in the regulation of research, enhanced corporate governance requirements, decimalization, a decline in the liquidity of small and mid-cap stocks, and other developments have been identified as contributing to the decline in the number of IPOs.

During the same period, there were a number of developments affecting the private capital markets. For example, the shortening of the Rule 144 holding period resulted in restricted securities being more marketable. Additional securities exemptions have proliferated, providing issuers with more funding alternatives. The emergence of new or additional investors in private securities, such as hedge funds, private equity funds, family offices, sovereign wealth funds, and crossover funds, have also led to a broader pools of capital. Despite changes to the IPO process implemented as a result of the 2012 Jumpstart Our Business Startups Act, there has been no significant sustained increase in the number of IPOs compared to historic levels.

Issuers, both privately held companies and public companies, continue to rely increasingly on exempt offerings to raise capital. According to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission's Division of Economic Risk and Analysis, registered offerings since 2012 accounted for approximately $1.4 trillion of total capital raised whereas exempt offerings, including Rule 144A and Regulation D offerings, accounted for approximately $2.9 trillion of capital raised. The availability of private capital at attractive valuations has contributed to the emergence of unicorns, or private companies valued at over $1 billion. The median market capitalization of IPO issuers has also increased as companies defer their IPOs and rely on private capital to fund their growth.

This trend is particularly notable in the technology sector. According to a study conducted at the University of Florida, the median age of a tech company from inception to IPO was four years in 2000. Between 2012 and 2018, the median age shifted to 11 years. Tech companies raised a median of $281 million prior to going public in 2019, compared to $64 million in 2012. This demonstrates that, at least for tech companies, significant amounts of capital are available in the private markets.

The IPO is not the sole capital formation alternative for tech companies to raise substantial amounts to fund their growth. In aggregate, $26.3 billion in private venture capital was raised by privately held tech companies in 2019. At the same time, perhaps not surprisingly, the number of tech company IPOs has declined. The number of tech IPOs fell from 33 in 2014 to 16 in 2015, and the numbers have not meaningfully increased in the years since, with 22 tech IPOs completed in 2019. To the extent that tech companies do pursue IPOs, their decisions to go public are generally based on considerations other than capital raising. Many tech companies now undertake an IPO in order to enhance the liquidity of the stock held by their existing security holders or the stock-based compensation instruments granted to employees. Others believe that having a publicly traded equity security will provide a valuable acquisition currency in the future.

The IPO Market

The IPO market has remained relatively stagnant and unable to return to pre-1999 numbers. In 2019, there were 160 IPOs, raising an aggregate of $45.8 billion in offering proceeds. As IPO numbers remain at low levels, and companies remain private longer, median market capitalizations increase as a result. The median IPO issuer's market capitalization in 2019 was $374 million, with a median of $91 million per deal raised. In addition, as noted above, small and mid-cap companies have increasingly been suffering from a lack of equity research coverage and limited liquidity. Institutional investors prefer to invest in large IPOs and, to an extent, this preference informs the advice given by banking professionals to potential IPO issuers.

Continuing a seven-year trend, life sciences companies dominated the IPO market by number of deals in 2019, demonstrating continued dependence by life science issuers on IPOs as a liquidity opportunity. In 2019, combined, life sciences, technology, and financial services companies made up 77.5% of IPOs by number of deals.

Financial sponsors including venture capital funds and private equity firms, together with other institutional investors, continue investing in promising private companies as they search for increased returns in a low interest rate environment. As noted in many studies, the significant growth that historically took place in the few years immediately following a company's IPO is now taking place while companies are still privately held. As a result, investing in private placements before the IPO, and thereby benefiting from this growth, is important to funds seeking returns. IPOs backed by financial sponsors have slightly declined over the last few years. According to an Ernst & Young report, financial sponsor-backed IPOs in 2019 represented 55% of all IPOs by number of deals, and accounted for approximately 77% of total capital raised in the public markets. In 2014, financial sponsor-backed IPOs accounted for 65% of all IPOs. These levels dropped in 2017.

A number of unicorns completed high-profile offerings in 2019. The top three IPOs by offering amount were ridesharing platforms Uber Technologies, Inc. and Lyft, Inc., which raised $8.1 billion and $2.3 billion respectively, and life sciences company Avantor, Inc., which raised $2.9 billion. The top 10 IPOs by offering amount raised accounted for 48% of all IPOs in the U.S. in 2019.

U.S. IPOs were dwarfed, however, by the IPO of Saudi Arabian-based petroleum and natural gas company, Saudi Arabian Oil Company. Saudi Aramco raised over $25.6 billion, making it the largest IPO in history, surpassing Alibaba Group's 2014 IPO, which raised $25 billion.

The divergence between private market valuations and public market valuations has perhaps contributed to the declining appeal of IPOs for tech companies. Private valuations may be impacted by a number of factors, and these valuations may not necessarily reflect the views of a broader investing base that participates in IPOs. Of course, private companies are also bypassing the public markets all together and completing M&A exits.

Life Sciences IPOs

The capital raising dynamics that have influenced tech companies and IPO issuers have not affected life sciences companies in the same way. The life sciences sector has accounted for the majority of IPOs in the U.S. by number of deals, or 38% of all IPOs between 2012 and 2019. This is due to the fact that there are fewer private capital alternatives for life sciences companies. Life sciences companies remain quite dependent on dedicated sector investors willing to commit capital for the long periods of time associated with research and development and the clinical development process. Therefore, the IPO remains the principal and potentially the only significant capital-raising alternative for life sciences companies.

Life sciences IPOs also evidence somewhat different dynamics. Life sciences companies need to establish strong investor sponsorship prior to undertaking an IPO. Having the sponsorship and validation of a respected sector investor can determine the success of the life sciences IPO. In 2018 and 2019, over half of the life sciences IPO issuers undertook a preIPO round within 12 to 24 months of their IPOs. The investors in these pre-IPO financing rounds are expected to participate in the subsequent IPOs. Indeed, many life sciences IPOs include significant insider participation from the pre-IPO private placement investors as well as from other affiliates.

Follow-On Offering Activity

In prior periods, the majority of underwritten follow-on public offerings were planned far in advance and were usually marketed for several days following their announcement. As a result of the coalescence of regulatory and market structure changes, follow-on offering activity has changed. The SEC has amended the rules relating to shelf registration statements, resulting in more issuers that are eligible to rely on these short-form registration statements and larger issuers, which qualify as well-known seasoned issuers, having greater flexibility in their use of a shelf registration statement.

In addition, changes to the securities offering related communications safe harbors provide greater certainty for issuers and their underwriters. Heightened volatility in the capital markets has led many issuers to approach their follow-on capital raising activities cautiously. Having witnessed the securities of companies that publicly announced follow-on offerings often shorted or being subjected to greater volatility, many companies have focused on follow-on offering alternatives that do not involve deal pre-announcements. This minimizes the possibility of investor front-running in anticipation of a follow-on offering pricing.

All of these concerns were heightened during the financial crisis, and led to the development of wall-crossed, or confidentially marketed, public offerings. In a confidentially marketed follow-on offering, an underwriter acting on an issuer's behalf wall-crosses institutional investors by confidentially discussing with them details of a potential follow-on offering. If sufficient interest is garnered during these confidential discussions, the issuer and underwriter will publicly launch the follow-on offering and make the offering available, at least for a brief period, to investors more broadly.

Follow-on offering activity has remained steady with no significant increases since a small jump in numbers in 2012. In 2019, 552 follow-on offerings were completed. Of these, 66% of the follow-on offerings were conducted on an abbreviated basis (with less than three days of marketing) or on an overnight basis (as confidentially marketed public offerings). According to a report published by investment bank William Blair, over 60% of follow-on offerings were conducted on an abbreviated or overnight basis between 2015 and 2019. Between 2016 and 2019, confidentially marketed public offerings accounted for over one-third of all follow-on offerings. In 2019, confidentially marketed public offerings comprised 36% of all followon offerings, and 18% of all follow-on offerings were structured as bought deals. In a bought deal, the underwriter purchases the securities from the issuer at a set price without having had the benefit of marketing the transaction and building a book of interest from investors. An issuer or a selling security holder may seek certainty of execution and pricing, without the volatility associated with a public announcement of an announcement. As a result, such an issuer or holder may prefer a bought deal to a confidentially marketed public offering.

IPO Alternatives

The growing interest in alternatives to IPOs, including special purpose acquisition companies, or SPACs, and direct listings, may lead to a paradigm shift

SPACs

Historically, some companies have considered mergers into already public SPACs as an alternative to the traditional IPO. Within a specified time period, usually 24 months, a SPAC that has undertaken an IPO must identify an operating company to merge into that meets the selection criteria disclosed in the SPAC's IPO prospectus. The number of SPACs that have gone public and initiated a search for operating company targets increased from 13 SPAC IPOs in 2016, which raised over $3.2 billion, to 59 in 2019, which raised over $12.1 billion.

Companies from a variety of industries completed mergers into SPACs in 2019. According to data collected by Rothschild & Co, a total of 26 mergers were finalized, with an aggregate enterprise value of $20.3 billion. Recently, more life sciences companies have elected to merge with SPACs. In 2019, life sciences company mergers into SPACs accounted for 23% of all SPAC mergers.

For many privately held companies, merging with and into a SPAC provides deal certainty. To the extent that the capital markets have experienced volatility and IPO windows open and close, a merger into a SPAC is not subject to these vicissitudes. The privately held company and the SPAC can negotiate a valuation subject only to receipt of SPAC stockholder approval for the merger. However, over half of the companies that have emerged from a merger with a SPAC have experienced poor aftermarket performance, as measured by the percent change in stock price, with one company trading at 84% below its price at the time its merger. The top three performing companies—Clarivate Analytics, an analytics services provider, Repay Holdings Corporation, a payments company, and OneSpaWorld Holdings, a health and wellness company—have traded at a 27% to 35% increase in price.

Direct Listings

Direct listings also have emerged as an alternative to the IPO. These allow the issuer to list a class of securities on a national securities exchange, which provides liquidity for existing security holders, including employees who hold options or restricted stock units. A direct listing does not involve raising new capital. As a result, direct listings may not be the answer for all issuers and are generally best-suited for larger, well-known companies with a strong investor base that do not require additional capital in the near term.

Both major U.S. stock exchanges, the Nasdaq Stock Market and the New York Stock Exchange, allow direct listings. As of Dec. 3, 2019, the Securities and Exchange Commission had approved direct listing rules for each of the Nasdaq's three tiers, the Nasdaq Global Select Market, the Nasdaq Global Market, and the Nasdaq Capital Market. Perhaps seeking to help broaden the appeal of the direct listing, in late November 2019 the NYSE submitted for approval to the Securities and Exchange Commission a proposed rule that sought to incorporate an option to raise capital into the existing direct listing alternative. Following its rejection by the Securities and Exchange Commission, the proposal was revised and resubmitted by the NYSE.

2020 Outlook

It is reasonable to anticipate that the trends described above will continue to affect the capital markets. Many of the capital formation related rulemakings undertaken by the Securities and Exchange Commission have focused on disclosure effectiveness, which on the margins may contribute to reducing disclosure costs for public companies, but does little to promote IPO activity. Expanding the opportunity for broader participation in private placements is unlikely to contribute to more dependence on the public capital markets. As noted above, the ability to test-the-waters for all companies for initial and follow-on offerings also is unlikely to lead to more public offerings or more publicly marketed offerings.

Originally Published by Bloomberg Law

Visit us at mayerbrown.com

Mayer Brown is a global legal services provider comprising legal practices that are separate entities (the "Mayer Brown Practices"). The Mayer Brown Practices are: Mayer Brown LLP and Mayer Brown Europe – Brussels LLP, both limited liability partnerships established in Illinois USA; Mayer Brown International LLP, a limited liability partnership incorporated in England and Wales (authorized and regulated by the Solicitors Regulation Authority and registered in England and Wales number OC 303359); Mayer Brown, a SELAS established in France; Mayer Brown JSM, a Hong Kong partnership and its associated entities in Asia; and Tauil & Chequer Advogados, a Brazilian law partnership with which Mayer Brown is associated. "Mayer Brown" and the Mayer Brown logo are the trademarks of the Mayer Brown Practices in their respective jurisdictions.

© Copyright 2020. The Mayer Brown Practices. All rights reserved.

This Mayer Brown article provides information and comments on legal issues and developments of interest. The foregoing is not a comprehensive treatment of the subject matter covered and is not intended to provide legal advice. Readers should seek specific legal advice before taking any action with respect to the matters discussed herein.