Foreword

Globalisation is quickening its pace. If the UK is to remain competitive in the battle for investment and wealth creation, business and government need to take action.

Nation is increasingly pitted against nation. As a result, the UK needs to benchmark itself against the best in the world to define where its comparative advantage lies. The new Deloitte Competitiveness Index is a unique attempt at capturing where the UK ranks today and enables a direct comparison between nations. It places the UK sixth amongst 25 world economies. However, by 2010, and assuming the continuation of trends of the last 20 years, our model suggests the UK will slip outside the top ten.

This is a clarion call that we must answer urgently. The speed and energy with which emerging economies are increasingly competing on an equal footing means there is no place for prevarication.

In order to take the pulse of British industry on this issue we surveyed UK business leaders. They identified that improvements in innovation and skills had and would be made. Similarly, concerns about the direction of the tax and regulatory systems should be addressed.

Globalisation presents an exciting opportunity that UK business and policy makers are well placed to address. We believe this should be at the top of boardroom and government agendas.

We trust this report will engage much-needed debate around how the UK maintains and enhances its comparative and competitive edge.

John Connolly

Senior Partner and Chief Executive

Deloitte & Touche LLP

Executive Summary

1. The Deloitte Competitiveness Index ranks the UK sixth out of 25 countries for its capacity to support wealth creation. We have developed a new index of competitiveness based on the key drivers of wealth creation – innovation, enterprise, investment and macroeconomic stability – and their impact on productivity in an economy. The UK is performing particularly well on macroeconomic and enterprise indicators, but less well in innovation and the business/corporate investment climate. In contrast, the US performs well in all of these areas and is ranked first by the Deloitte Competitiveness Index. Unlike other G7 countries, the US is likely to retain its position.

2. Business leaders need to inject urgency into the debate about how the UK creates the next generation of knowledge based wealth. Change in the global business operating environment has accelerated over the past five years, compelling businesses to adapt rapidly and flexibly to the new challenges and opportunities they face. Unless the pace of policy change is similarly stepped up, the UK, along with other G7 countries, will slip down the rankings. For instance, only a third of business leaders feel the UK is the best place in the world to run a business. Nearly half of UK businesses report they would relocate headquarters in the future if domestic conditions made it difficult to operate. Policy makers must ensure such a situation does not arise. If the UK is to maintain or better its position, areas to be addressed should include innovation and business investment.

3. Rapidly accelerating globalisation should be high on boardroom agendas and the CEO must take ownership. UK business needs to fashion a new business model and operating processes that use the whole world for wealth creation. This fundamental change in mindset needs to be focused around three factors. First, reshaping operations by relocating business processes – within and beyond the UK – to their best possible home. These decisions are increasingly driven by abundant pools of skills such as the surplus of engineering graduates in India, accountants in the Philippines or call centre agents in Scotland. Our research shows this process is very much underway with UK-based companies having more than one-fifth of all non-customer operations located outside the UK. Second, UK businesses must build a capability within the organisation to evaluate constantly and optimise the network of operations. Just 3% of UK companies consider relocating their headquarters on a regular basis, according to our research. Finally, given the speed of change, we would urge businesses to press harder on the accelerator. CEOs need to take responsibility for oversight of the impact of globalisation on their business and play an active role in shaping the broader policy agenda.

In building a new operating model we identify seven critical factors:

- Reduce organisational layers across (international) operations.

- Delegate to empower local decision making, but retain accountability.

- Empower local operations on issues such as pricing and cost structures to reflect local markets’ conditions.

- Centralise non-core processes into lower-cost jurisdictions.

- Form partnerships with local stakeholders to build reputation before moving into an area and once established build trust through a strong ethical stance.

- Work with government to build understanding around the business requirements and to articulate the business impact of any policy changes on skills, tax and regulation.

- Clarification of the role of headquarters in this model and how it oversees its distributed operating model.

4. Governments must address the competitiveness policy dilemma. To be fit for the future, governments must balance the short-term need for agility and flexibility with the long-term need for macroeconomic stability. This report suggests government should pursue a dual agenda based on macroeconomic stability alongside continuous incremental improvements around the innovation, tax and regulatory regimes. There are three priorities to be addressed. First, the amount of research and development (R&D) conducted by firms needs to be increased. This may mean re-evaluating the scope of the R&D tax credit system and improving its application to ensure greater simplicity and consistency. Second, the tax system is too complex and the costs of compliance too high for large and small businesses alike. We need a period of stability in the tax system, as well as a clear commitment to align growth in tax revenues with a growth in corporate profitability. Third, while many businesses understand the rationale for a robust regulatory system, many still do not consider the regulations sufficiently ‘smart’ to represent anything other than an additional cost. The Better Regulation Executive should redouble its efforts to ensure any regulation is good regulation.

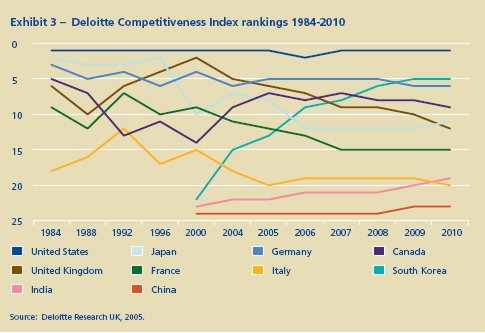

5. The competitiveness agenda is a joint one between government and business. Business and government often see themselves as separate champions of the competitiveness cause with little in common. In the UK, it is important not to allow globalisation to drive business and government apart, rather it should be used as an agenda to tie both parties together. A joint agenda must be recognised and binding actions placed against it, if the UK is to retain its position in the world rankings and not slide to 12th by 2010 (see Exhibit 3). Governments need to provide the policies which make the UK an attractive place to do business. CEOs need to benchmark themselves against the best in the world and keep the pressure on governments by challeging the status quo. It is vital that the UK rises to the challenge.

Comparative Advantage In A Competitive World

Globalisation is quickening its pace. The last five years have seen a new era for business with seismic shifts in technology, capital flows and trade liberalisation, which impacts business practices. Knowledge workers from across the world can engage in the global labour market. New world-class research and development hubs in emerging economies provide support for businesses in the developed world. Products launched on the market today have ever shorter life spans. Proximity no longer has to be geographical.

Against this background, companies want to know the best places in the world to operate, while policy makers need to benchmark themselves against the best in the world. This report attempts to establish the connections between these two interdependent agendas by fusing two research methods.

First, to benchmark the UK’s competitiveness position we identified the drivers of wealth creation and productivity (see Exhibit 1). By comparing these key drivers – innovation, investment, enterprise, human capital and macroeconomic stability – within an economy with the overall rates of productivity in 25 countries, we developed the Deloitte Competitiveness Index. This index provides a ranking of countries in terms of their capacity to support competitive and productive businesses.1.

Second, to understand how UK-based companies best align operational and locational decisions we surveyed business leaders on: why they retain their headquarters in the UK; what drives decisions to move functions abroad; what are the key criteria in aligning operations and location (Exhibit 1). Three hundred business leaders participated in a telephone survey and ten case study companies participated in in-depth interviews.

As one of the world’s most open economies, the UK will face greater demands in defining its competitive advantage. The remainder of this report sets out to address four key questions:

- How does the UK rank as a place to support competitiveness? How do countries score on different drivers of competitiveness such as the macroeconomic climate, enterprise, human capital, competition and innovation?

- How do UK businesses create value by utilising the comparative advantages of their UK and overseas locations – today and in the future?

- How can policy better support UK competitiveness?

- How do policy makers and businesses work together to drive forward their shared interest?

The speed of change means that the UK has a major challenge ahead, requiring vision from both business and policy communities. This report lays out an agenda for both.

How Does The UK Rank As A Competitive Location?

As companies trade places, governments are taking a keen interest in international rankings and performance indicators as measures of their success in improving economic performance by closing the productivity (or wealth creation) gap.

Against this backdrop, the UK needs to benchmark itself against the best in the world. The Deloitte Competitiveness Index gauges the potential of nations to create wealth, measured through productivity (see the Appendix for the full approach taken). The advantages of this model are:

- It uses established European Union and UK government supply-side indicators as a base for the sub-indices.

- It does not incorporate qualitative views into the model itself.

- It is based on a 20-year data panel allowing a long-term view to be taken.

- It has a strong, positive correlation with Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth.

The UK productivity gap

The UK’s productivity gap with the US, measured as GDP per employee, is around 25%. Further, with France the gap is 11% and with the G7 economies it is 10%, although the level is similar to Germany and above Japan. Using GDP per hour worked, the UK is ahead of Japan but behind Germany, the US and France.

The UK’s gap with Germany and France emanates from differences in capital intensity and labour force skills (specifically intermediate skills). It lags the US mainly on Total Factor Productivity (TFP), the residual left over after all capital and labour have been incorporated into growth accounting models. This residual is important as an indicator of the business base of competitiveness.

Sources:

www.ons.gov.uk; Porter, M. and Ketels, C. (2003): UK Competitiveness: moving to the next stage DTI economics paper No. 3 (DTI/Pub 6580/5.5k/05/03/NP URN 03/899).The Deloitte Competitiveness Index

Our approach takes the areas that are acknowledged company-level performance drivers as well as indicators of national competitiveness: macroeconomic stability, enterprise, innovation, business investment, competition (or openness) and human capital – to determine the overall competitiveness of a nation. These are also the areas covered by the UK government’s own competitiveness indicators and are also similar to the Lisbon Agenda targets. The Deloitte Competitiveness Index amalgamates these variables into a general index that shows the capacity of a particular economy to generate and support wealth creation (in other words, productivity growth) through competitive businesses.

The Deloitte Competitiveness Index measures TFP, making it quite different to other international rankings. We took a basket of indicators for each of macroeconomic stability, enterprise, innovation, business investment, human capital and competition. We created a sub-index for macroeconomic stability, enterprise, innovation and business investment. The indicator for competition is a proxy for the openness of the economy (imports and exports divided by GDP) and human capital is proxied through years of schooling. Any interdependencies between sub-indices are incorporated into the model (see Appendix). A total index from the four sub-indices and two variables was calculated and compared to the wealth creation potential of a country measured through TFP.

It is important to note the difference between the Deloitte Competitiveness Index and its sub-indices can be very marked. This is because the total model captures the underlying rates of change in the sub-indices and their impact on TFP. For example, Finland has low rankings for innovation, macroeconomic stability and enterprise yet comes out third overall. What this means is that within Finland the index factors are strong drivers of wealth creation.

The Deloitte Competitiveness Index places the UK sixth in the world as a competitive location, made up of the following:

- Fifth for macroeconomic stability: low inflation, consistent growth and stable employment provide firms with the security they need to make long-term decisions about their business. This ranking has improved from 19th in 1984.

- Fourth for enterprise: a pro-risk culture, combined with relatively easy access to capital and a strong and dynamic business base ensures that there is a supply-chain of creativity and new ideas in the economy. This ranking has improved from sixth in 1984.

- 12th for innovation: R&D is the life-blood of business competitiveness through the generation of new products, new processes and new markets. This ranking has deteriorated from sixth in 1984, although this may be because of a comparatively low propensity to patent in the UK.

- 12th for investment: effective regulatory, tax and interest rate regimes are preconditions for corporate/business investment. This ranking has improved from 14th since 1984, but, assuming the pattern of the last 20 years holds, may deterioriate to 16th by 2010.

The US scores highly as a location for business competitiveness overall and through each of the competitiveness drivers. Similarly, in line with other international rankings, the Nordic countries also do well with Sweden, Finland and Denmark coming second, third and fourth respectively. In all these cases, productivity growth is strongly fuelled by the Deloitte Competitiveness Index’s four sub-indices.

This should come as little surprise and demonstrates that there is no one policy panacea to be competitive given the different approaches amongst these nations:

- The US had strong productivity growth during the 1990s on the back of an innovation and entrepreneurship boom and a strong investment climate, particularly in the area of access to finance. Although its growth has subsequently slowed, the US still has the largest flow of inward and outward Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). Many US businesses are globally competitive and are supported by government investment at levels in excess of those in other countries.2

- The Nordic countries have put in place policy mechanisms to link innovation with entrepreneurship and investment to produce strong productivity growth. This is combined with substantial public investment in the innovation infrastructure and some of the highest business expenditure on R&D in the world.

- Germany performs well in relation to other European and G7 countries because innovation and skills are the main drivers of wealth creation. Interestingly, Germany ranks highly for its stable economy. Despite sluggish performance in growth and employment, the economy has continued to maintain strong export performance.

2010 and the challenge ahead

The next five years could bring a shift in the global balance of national competitiveness. Assuming that changes continue at the pace of the last 20 years, the Deloitte Competitiveness Index forecasts the US is likely to remain the most competitive nation. Further, only Italy of the G7 nations will retain the same position (20th). All mature economy Deloitte Competitiveness Index rankings are forecast to deteriorate with the UK likely to slip from currently being sixth to 12th (see Exhibit 2).4

By contrast, emerging economies are likely to fare much better, notably South Korea, China and India. South Korea’s competitiveness is forecast to rise from 14th to fifth in 2010, with substantial increases in all sub-indices. China’s rise from 24th to 23rd will be driven largely by an improvement in its enterprise sub-index.

World rankings from a business perspective

China is a growing market with a strong entrepreneurial and risk taking culture and 15% of UK business leaders we surveyed felt that it was a good place to locate business functions. India will likely rise from 22nd to 19th with a particularly noticeable improvement in innovation.

Business leaders we spoke to were swift to point out that, by moving some business functions and R&D to India, they were benefiting from lower labour costs and stronger capabilities. One company highlighted the intermediate skills based in India particularly suited products that required constant, incremental innovation but maybe did not require substantial ‘blue sky’ research. This is further supported by our work showing UK financial institutions employing global best practice in offshoring.5

The potential drop in the overall rankings of the UK over the next five years must be of concern to policy makers. Our model exhibits a strong, significant and positive correlation between growth in the Deloitte Competitiveness Index and growth in GDP. Any drop in the rankings must therefore translate into a potential deceleration in wealth creation.

Exhibit 4 – Countries which CXOs ranked the best to run a business, by sector

|

All |

Primary/Utility/ |

Retail/Wholesale/ |

Financial & Business Services |

|

|

% |

% |

% |

% |

|

|

Europe (inc. UK) |

60 |

58 |

63 |

59 |

|

53 |

44 |

61 |

55 |

|

33 |

24 |

37 |

37 |

|

9 |

15 |

4 |

8 |

|

North America |

35 |

32 |

38 |

34 |

|

32 |

26 |

38 |

33 |

|

Asia |

30 |

39 |

26 |

25 |

|

25 |

32 |

23 |

8 |

|

15 |

25 |

13 |

8 |

|

6 |

7 |

6 |

6 |

|

Australasia |

12 |

11 |

7 |

18 |

|

12 |

10 |

7 |

17 |

|

South America |

2 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

|

Africa |

2 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

|

"Don’t know" |

16 |

16 |

11 |

21 |

Source: Deloitte Research UK, 2005.

If business really is as globally mobile as business leaders argue, then this points potentially to fragility in the developed world’s business base. The exposure of the UK economy to global dynamics is emphasised by the fact that only one-third of UK business leaders surveyed feel that the UK is a good place to run a business (see Exhibit 4). Further, as we discuss in the next section, a dynamic business model is emerging that is not constrained within national borders. This model uses the resources and capabilities from around the world to build and sustain competitive advantage. The warning signs are there: the UK needs to respond. The next section explores the issues for business and is followed by the challenges for government.

Does London drive UK competitiveness?

Most of the business leaders with whom we held in-depth interviews were based in London and argued forcefully that the benefits of the capital – access to clients, highly skilled labour, innovation networks and finance – far outweighed the costs. It was seen as key to competitive advantage for their business. One pointed out that the costs of moving headquarters away from London were simply too high to contemplate; another said London was the only place in the world where there was such a rich supply of talent, culture, networks and finance all in one place.

How important is the City of London as a place to do business?

We asked all the business leaders based in London from our survey how important the City was to their business. Nearly 60% reported it was critical or very important. Over a third of finance respondents and a half of manufacturing companies thought that the City was critical or very important. Over 50% of service companies view the City as critical or very important.

Why is it so important to be located in London?

The City of London has a unique combination of factors that businesses tap into to drive competitiveness and was ranked top by a recent survey of European cities:6

- Access to growth finance.

- Cluster of supporting businesses and complementary skills/assets.

- Active government policy supported by strong investment in new sectors and markets.

- Pool of talent and capital.

|

Reason for staying in London (verbatim responses) |

% of those based in London |

|

Access to clients |

35 |

|

Easy access to networks and infrastructures |

21 |

|

Access to highly skilled potential employees |

12 |

|

Nature of business |

7 |

|

Access to supply chain |

12 |

|

Capital city (quality of life, culture, dynamics, knowledge capital) |

9 |

|

Financial centre |

9 |

Source: Deloitte Research UK, 2005.

Footnotes

1 Our approach, discussed in some detail in the Appendix, is just one way of developing such an index. Others include the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Index and the IMD’s World Competitiveness Yearbook rankings.

2 For example, the US government spends the highest percentage of GDP on R&D in the world at some 3.2% of GDP.

3 See the Appendix for components of sub-indices and construction of index.

4 This forecast is based on assumptions that the trends and policies continue on the trajectory of the last 20 years.

5 Global Financial Services Offshoring. Deloitte. Global Financial Services Industry. Nov 2005

6 The Competitive Position of London as a Global Financial Centre. Corporation of London. November 2005. Financial Times, 6 October 2005, "London still top city for European execs" reports on a survey produced by the European Cities Monitor.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.