The United Kingdom is formally applying to join a trans-Pacific trade group whose members constitute about 8% of British exports (very roughly the equivalent of its exports to Germany). It is called the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPATTP). This trade agreement succeeded the trade arrangement called the Tran-Pacific Partnership which the Trump administration withdrew the US from.

What is the CPATTP?

The CPATPP currently contains 11 medium sized and affluent states as members. These are Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore and Vietnam. Perhaps Paddington Bear will now do a roaring trade in marmalade between the UK and Peru. The British government hopes the post-Trump US will also join CPATPP. If the US joins CPATPP it would enhance Anglo-American trade which in turn could be boosted by a specific Anglo-American trade deal. Observers note the new US administration is cautious of completing new trade deals as it - perhaps ironically - tries to rejuvenate the US economy.

Response from Critics

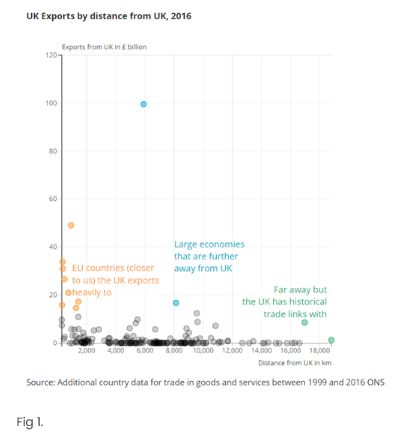

Critics consider the British application to be symbolic in nature. Critical studies indicate joining the agreement would only increase British GDP by an insignificant extent. This is partly because the membership of the agreement rings the Pacific, far from the UK on the shores of the Atlantic. Underpinning those views is the argument that trading with your neighbours is by far the most important priority. Figure 1 demonstrates this through the current British trade position. The top orange figure is Germany, where Britain exported £50 billion by value in 2016. The distance trading partners in green are Australia (more trade) and New Zealand (less trade). If one added the other target countries for UK trade diplomacy into trade agreements such as India, Australia, New Zealand and the Gulf, the addition to British GDP is still less than 1 percent in the long term. If one assumed the government did a trade deal with China, critics state the accumulated long-term growth in GDP from trade deals still does not increase beyond one percent. The Appendix gives recent British trade trends with these countries as background material. On the debit side, commentators point out that leaving the EU will result in a long-term foregone opportunity for trade with figures for this varying, but 4% of GDP has been cited.

View from the British Government

The British government sees it differently. The application shows Britain's trade ambition. It is to be a champion of free trade. Britain will trade with willing countries. Many of those will be medium or small or with internationally exposed economies. According to the Financial Times, British trade with CPATPP members is £111 billion a year and has been growing at 8% annually since 2016 1 when the Brexit referendum was held. Benefits of CPATPP membership are liberalizing digital trade, lower tariffs on luxury British items like whiskey and on complex goods like automobiles as well as liberalizing visas which may assist the service sector.

The EU has been declining as a proportion of British trade for some years now, even though it remains the biggest and most important component of that trade (see Figure 2). British trade with non-EU countries has been growing for years (see Figure 3). The UK is now finding its own trade policy that it hopes will suit its strong services sector as well as hopefully reinvigorate its manufacturing thereby positively impacting on its regional "levelling up" exercise. It is ambitious, but necessarily so following Brexit and considering longstanding regional economic disparities and the growth of regional nationalism.

To view the full article please click here.

Footnote

1 'UK applies to join trans Pacific trade group', G Parker and A Williams, 30 January 2021, www.ft.com

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.