Summary and implications

The Technology and Construction Court (TCC) considered the meaning of a "construction contract" and "construction operations" in sections 104 and 105 of the Housing Grants, Construction and Regeneration Act 1996 (as amended) (HGCRA) and held on 29 August 2013 that a deed of collateral warranty was a construction contract under the meaning of the HGCRA.

- This has various potential implications, claims under collateral warranties may be referred to adjudication under the HGCRA.

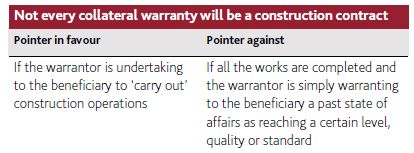

- Not every deed of collateral warranty will automatically be a construction contract, it depends on the specific wording.

- The implication of HGCRA payment provisions into collateral warranties is an academic issue raising only an entitlement to stage payments of the sum payable under the collateral warranty (nominal if any), not an obligation to pay based on works value.

The Housing Grants, Construction and Regeneration Act 1996

The HGCRA (supported by the Scheme for Construction Contracts (England and Wales) Regulations 1998 (SI 1998/649)) sets out the meaning of a "construction contract" (section 104) and "construction operations" (section 105) and provides that only those contracts that fall within the meaning of a construction contract are subject to the provisions of the HGCRA.

The HGCRA implies a number of provisions into contracts that fall within the definition of a "construction contract" including:

- the right to refer disputes to adjudication;

- the right to be paid by instalments;

- the requirement for an adequate payment mechanism;

- the right to suspend performance for non-payment; and

- a prohibition on conditional payment provisions.

The focus in a recent case was the right to adjudicate.

Parkwood Leisure Ltd v LaingO'RourkeWales andWest Ltd [2013] EWHC 2665 (TCC)

In 2006 Orion Land and Leisure (Cardiff) Ltd (Orion) appointed Laing O'Rourke (Laing) to design and build a leisure facility in Cardiff under a standard JCT Design and Build Contract. Cardiff City Council let the facility to Orion on a 25 year lease and Orion sub-let the facility to Parkwood Leisure Ltd (Parkwood) to provide facilities management services. Laing provided a deed of collateral warranty to Parkwood.

a) Facts

A dispute arose concerning the defective design and/or installation of the air handling units at the leisure facility. Parkwood wrote a letter to Laing in accordance with the Pre-Action Protocol for Construction and Engineering Disputes setting out their claim. Laing rejected the claim and Parkwood started court proceedings seeking, amongst other things, a declaration that the deed of collateral warranty was a construction contract for the purposes of Part II of the HGCRA and as such was subject to the statutory adjudication rules.

Akenhead J held that the deed of collateral warranty in favour of Parkwood was a construction contract for the purposes of Part II of the HGCRA.

b) Court's considerations

In deciding that the deed of collateral warranty was a construction contract Akenhead J considered the following:

What is a construction contract?

- Section 104(1) provides that a construction contract is an "agreement...for the carrying out of construction operations". Akenhead J commented that "it is clear that Parliament intended a wide definition".

- A construction contract does not have to be wholly or even partly prospective. It is common for construction contracts to be finalised after the works have started.

- Usually where one party to a contract agrees to carry out and complete construction operations it will be an agreement "for the carrying out of construction operations".

The wording used in the deed of collateral warranty:

- The recitals of the underlying building contract said that the contract was "for the design, carrying out and completion of the construction of a pool development". There could be no dispute as to whether this was construction contract and that wording was replicated in clause 1 of the deed of collateral warranty.

- Clause 1 of the deed of collateral warranty also provided that Laing "warrants, acknowledges and undertakes". Akenhead J concluded that these words were not intended to be absolutely synonymous and related to the past as well as the future recognising the fact that works under the building contract were in the course of construction and remained to be completed.

The deed of collateral warranty will give rise to ordinary contractual remedies therefore if Laing completed the works not in accordance with the building contract (i.e. with defects) there would be an entitlement for Parkwood to claim for damages because there would be a breach of contract.

Akenhead J therefore concluded that the deed of collateral warranty is clearly "for the carrying out of construction operations".

c) Effect of the ruling

This is the first time in a reported judgment that the court has considered whether a deed of collateral warranty is a construction contract.

It potentially opens the door to an increase in claims under deeds of collateral warranty being referred to adjudication, which may have advantages for beneficiaries by giving a quicker and cheaper dispute resolution than litigation but is less likely to be welcomed by warrantors, as the incidence of claims under deeds of collateral warranty may increase if a quicker and cheaper dispute procedure is available.

d) Future considerations

Not all collateral warranties will be construed as construction contracts under the HGCRA. Akenhead J said that "one needs primarily to determine in the light of the wording and of the relevant factual background each such warranty to see whether, properly construed, it is such a construction contract for the carrying out of construction operations".

e) Payment issues

If a collateral warranty is construed to be a construction contract and adjudication provisions are implied into it, what then happens to the payment and suspension rights that are also implied by the HGCRA? The judgment leaves this question unanswered.

There has been much subsequent discussion on the potential effect of payment provisions that may be implied into a collateral warranty by the HGCRA if a collateral warranty is a construction contract. The HGCRA provides that in the absence of express HGCRA compliant payment provisions, the Scheme for Construction Contracts will be implied. Contrary to the views expressed by various commentators the Scheme only provides that if the parties have failed to agree periodic payments of the contract price and timing then these will be implied, it does not seek to dictate the contract price. The periodic payments required by the Scheme would only be applied to the contract price ie payment of any amounts explicitly payable under the collateral warranty. It would not be within the contemplation of the parties to the collateral warranty that the beneficiary would be responsible for payment for the works under the underlying building contract or appointment. Discussion on payment provisions is therefore academic. The only payment due that such provisions could apply to is any consideration within the collateral warranty itself, which will be nominal (ie a pound or peppercorn) if it exists at all.

If warrantors wanted beneficiaries to be obliged to pay for the works in circumstances where the employer is no longer in the picture, this would have to be explicitly set out in the collateral warranty. This is done in the context of step in rights, ie an obligation to take over payment obligations if such rights are exercised. Such a position already exists in collateral warranties that include such provisions. Beneficiaries will not accept obligations to pay for works under a building contract or appointment other than in circumstances where they step in.

f) Third party rights

Third party rights schedules are a part of (and usually set out in a schedule to) a building contract or appointment (which are themselves clearly construction contracts). The third party rights schedule to a building contract or appointment often contains wording similar to that seen in the collateral warranty in the Parkwood case, i.e. 'the Contractor ... warrants and undertakes to the Beneficiary ... to comply with all the obligations ... under the Building Contract.'

The question then arises of whether, following the logic in the Parkwood case, the third party rights are themselves a construction contract. One view is that a third party by definition cannot be a party to the building contract or appointment. But following the logic of there being a commitment to carry out construction operations, then by analogy it would appear that the rights may be a construction contract, in which case all the same issues may arise.

g) Other ancillary documents

There are a large number of ancillary documents to a building contract which were not considered by the judgement in Parkwood, such as parent company guarantees. These documents could potentially be considered construction contracts following this case, depending on their wording.

h) Looking forwards...

The Parkwood decision clearly raises issues on how collateral warranties, third party rights and other documents ancillary to building contracts and appointments may be viewed. Many of the implications of the decision appear to result in unintended consequences and it will be interesting to see the impact of the case going forwards. For example, if a collateral warranty is a construction contract (i.e. a commitment to carry out works), can the beneficiary seek specific performance of that obligation, and how does this sit with a potentially only nominal payment obligation. For beneficiaries the right to adjudicate under collateral warranties, i.e. the direct point arising from the Parkwood decision, may have certain attractions, but one can anticipate that the suggestion, however illogical and unintended, of the beneficiary acquiring payment obligations could raise concerns for beneficiaries, and equally that warrantors could be concerned if they might face orders for specific performance without any corresponding right to be paid.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.