AI offers many areas of application for improving athletes' sporting performance and preventing injuries. However, it is not only athletes themselves who have an interest in their comprehensive AI-processed data, but also the sports organisations with which they are contractually affiliated or whose rules they are subject to. In this blog post no. 11 of our series, we use sample use cases to explain what sports organisations need to be aware of when using AI in connection with athlete data.

Hardly anywhere else is data about the body, behaviour, performance and psyche of people as crucial and comprehensive as in elite sport. Such data is often not limited to the "workplace", i.e. athletic performance in training or competition, but goes far beyond that. After all, in today's practice, elite sport means optimising and monitoring performance on a daily basis so that athletes meet all the physical and mental requirements to deliver world-class results for their nations, clubs and themselves and to realise their full potential. To increase the physical and mental performance of athletes, sports organisations are increasingly using AI, as AI promises not only more efficient but also more objective monitoring and evaluation of such data as well as recording circumstances that are difficult or very time-consuming for humans to determine due to the sheer volume of data. Those organisations that set the regulatory framework for their respective sports also use AI to support their legal and regulatory tasks.

It is usually not the athletes themselves who ultimately monitor and analyse their data, even if they collect it using various tracking devices. Monitoring and evaluation is often carried out by the sports organisations, which can give the athlete instructions based on this information. All types of performance data from training and competitions, recovery data and injury data through to partly genetic or comprehensive and detailed data about the athlete's body and behaviour can be considered. Some sports organisations use this data exclusively in the interests of the athlete, while others use it for their own sporting and ultimately commercial success, for example to make tactical decisions, uncover athletes' weaknesses, determine the sporting influence of individual athletes in a team or discover talent and predict their performance potential.

However, for a sports organisation to be allowed to use athlete data in the context of AI to the desired extent and at the same time protect the rights of athletes, it must comply with various legal requirements, particularly in the area of data protection. In addition, a sports organisation will have to deal with its own ethical principles and rules, which often exist.

Legal constellations in the area of sports performance

When it comes to the use of athlete data in elite sport, a distinction can be made between three constellations when it comes to the legal assessment of data use by a sports organisation:

- The Sports Organisation as Employer: The athletes are contractually bound to the sports organisation; they perform their services primarily for the sports organisation, receive a salary for this and are subject to its instructions. The sports organisation has its own economic interest in the sporting performance of each athlete or employee. This scenario is typically found in team sports, for example with a club as the employer, but in rarer cases also with sports associations. Under Swiss law, the sports organisation as employer may only process athletes' personal data if this is necessary for the performance of the employment contract or for assessing the athlete's suitability for the same (Art. 328b CO). The processing of athlete data can go a long way, particularly in the context of a club, because the club also needs to know the athlete's physical condition in order to be able to use the athlete and assess his suitability for competitions. In addition, in this constellation, both the athlete and the sports organisation are normally also subject to the rules of the national and international sports association to which they belong. Although these rules do not restrict the use of athlete data, they may contain certain ethical (i.e. supra-legal) requirements that are relevant for the interpretation and application of the applicable provisions.

- The Sports Organisation as Service Provider: Athletes obtain services from a sports organisation to improve their own performance (e.g. by collecting and analysing their data). In doing so, they act primarily as their own companies (often also as sole proprietorships). The use of the data is somewhat less transparent for the athletes compared to the above employment relationship, because the interests and economic orientation and data use by the service provider are not readily recognisable. Therefore, in this scenario, it will also be necessary to regulate the purposes and parameters of data processing within the framework of a contract (who is authorised to dispose of which data for which purposes, how and for how long?) In addition, an athlete in this scenario is often not protected by further regulations in relation to the service provider, apart from their relationship with a national and international sports federation, which can then also have a reflex effect on their relationship with the sports organisation as service provider. This scenario exists, for example, in the case of performance centres whose services are used by an athlete or in the case of (usually national) sports federations with which an athlete is contractually associated and which provide the athlete with comprehensive support or assistance in his or her activities, but without an employment contract. Nevertheless, in these scenarios, contract law may apply under certain circumstances and, in this respect, a binding interest may exist; however, this protection is relatively weak.

- The sports organisation as regulator or controlling authority: These are the sports governing bodies of the athletes concerned, i.e. primarily non-governmental organisations (such as the international sports federations in particular), the organisations of the Olympic Movement (such as the International and National Olympic Committees and their organising committees) and organisations that make a scientific contribution to elite sport. In addition to setting competition rules and organising competition series, leagues and the like, these sports organisations are also particularly concerned with the safety and fairness of their sport. In addition, there are control bodies that are independent of the rule-makers, such as the doping authorities or internal investigative bodies. Athletes usually submit to such rules in pre-prepared declarations of consent. The purposes of processing, the types of processing and the scope of processing in this scenario are regulated both in regulations issued under private law (e.g. Swiss Olympic's Articles of Association on Doping) and in some cases by law (e.g. the Sports Promotion Act).

In all the above constellations, there are numerous possible applications of AI. In the following, we have therefore depicted exemplary (though realistic) cases for each constellation and discuss the legal challenges that arise and how these can be solved. We also list some other possible cases.

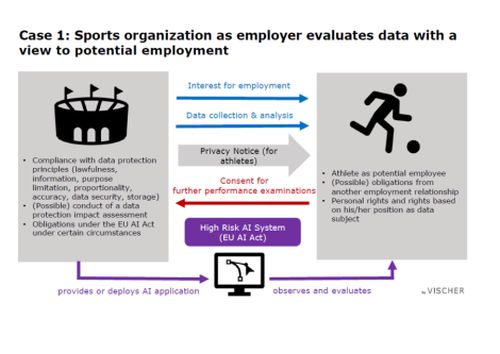

Case 1 - Employer analyses data with a view to potential employment

The employer, be it a team sports club or a professional cycling team, has a primary interest in the recruitment, monitoring and performance of strategically fit and healthy athletes.

For our case 1, a football club based in Switzerland is looking for a right winger for its first team to strengthen its forward line and increase its scoring ability. Due to the strategic and sporting orientation of the football club and the head coach, the football club is looking for a young, strong and powerful goal scorer who can also work with the experienced centre forward already employed and who can also provide the latter with the necessary support. For scouting, they use an AI application customised to their needs. This AI application has access to all known data collected on players from Switzerland and the EU over the last 15 years relating to their performance on the pitch (e.g. heart rate, running distance, running speed, successful passes during matches, health and performance data from sports medicine examinations, etc.). In addition, the football club uses its scouts to attend matches and training sessions at other football clubs where players who may be suitable for the position take part, using cameras specially manufactured for the AI application to record the players and feed the football club's AI application with the relevant data. In the next step, the football club can then enter the corresponding requirements for the predefined values in the AI software (which relate in particular to athleticism, free-running behaviour, technique or passing behaviour). Based on all the available data, and taking into account the desired outside forward position (which requires rather difficult, but nevertheless important passes with a lower average success rate than a midfielder, for example), the AI application calculates which players have the greatest potential for success (or the probability of successful assists and goal-scoring ability). The AI application provides the football club with a preselection of 5 players who are potential signings and who can be analysed more closely by the football club's scouts.

The use of AI therefore begins with the acquisition of athletes as potential employees. The football club determines their performance data as comprehensively as possible before establishing an employment relationship, either itself or through third parties. Much of the data used in scouting comes from publicly accessible events (e.g. matches, public training sessions, etc.). However, the employer collects some data (e.g. from medical examinations/tests) in a confidential context and before the contract is signed (in these cases with the consent of the players concerned). For these reasons, a sports organisation must always ask itself how, when, on what legal basis and for what purposes it collects and analyses data with regard to potential employment. In addition, the potential success of an athlete calculated using an AI application and the data collected prior to the employment relationship to the extent outlined above has a major impact on contract negotiations - in particular on the salary and other monetary benefits for the athlete.

At first glance, the problem in the above case is that the athlete, as a potential employee, has no contractual relationship with the football club in question. He has neither applied for the club nor is he aware of the club's interest. Although it is common practice (and therefore known in the relevant circles) for scouts to observe the performance of potential players at matches and sometimes public training sessions, the extent of this performance recording using camera systems, some of which are specially manufactured, and the feeding of proprietary data sets and their analysis with AI applications is taking on a new dimension. From a data protection perspective, however, we believe that there is no violation of personality rights in the present case, even with such comprehensive data collection, as at least in the case of publicly accessible training sessions and matches, the players, as data subjects, make all data that can be recognised with the naked eye (e.g. running speed, pass success rate, etc.) generally accessible within the meaning of Art. 30 para. 3 FADP, unless they expressly prohibit such processing. However, when processing such data, the football club must comply with the principles set out in Art. 6 and 8 FADP (which should not be difficult given the customary nature of the procedure) and provide appropriate information on the collection and use of this personal data in accordance with Art. 19 FADP (e.g. as part of a data protection declaration). The data is collected directly from the player because he himself is being monitored; he would therefore basically have to be informed that his data is being collected for the purpose of analysis.

Because football clubs often attend matches and training sessions abroad, particularly for scouting purposes, and are therefore likely to use the corresponding application in the EU to analyse foreign players, the GDPR also applies. Even if the club operates from Switzerland, it must expect that behavioural monitoring will take place on the territory of the EEA and that it will therefore be applied in accordance with Art. 3 para. 2(b) GDPR, as the club is expressly interested in creating a profile of the player in question. This in turn means that, in addition to the requirements under Swiss law, there must also be a legal basis for data processing. We assume that EU data protection authorities will automatically require consent in these cases, but we believe that, in view of the fact that the athlete's professional characteristics are being assessed, a legitimate interest within the meaning of Art. 6 GDPR can be established, i.e. the athlete would not have to be asked in advance.

If the football club carries out the data collection directly within the territory of the EU, it must also expect to fall under the EU AI Act, which qualifies this type of AI application as a "high-risk" AI system due to the fact that the athlete is a potential employee. This would result in various other obligations. However, if the Swiss football club uses an existing (versus a self-developed) AI application, it may be able to avoid the application of the AI Act as long as the output of the AI is not used in the EU. The football club would therefore have to pay attention to this (see Part 7 of the blog series on the AI Act).

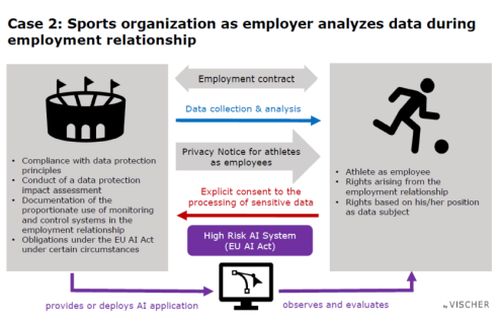

Case 2 - Employer analyses data during the employment relationship

The coaching staff uses an AI application to determine the most promising line-up of an ice hockey team for the upcoming weekend game. The AI application uses a comprehensive data set that contains the performance and recovery data of all players (data such as recovery, sleep quality and physical performance and fitness are exported by the players from their sports watches and other sports gadgets to a platform of the ice hockey club with which they have a profile), as well as all the data collected on the ice field from their own players and the opponent's various plays. Based on all these values, the AI application can make suggestions to the coaching staff as to which players in which positions are most suitable for a specific game. The AI application not only takes into account certain strengths of the opponent, but can also use all centrally available athlete data to make statements about whether the probability of scoring and the risk of conceding a goal changes if player A plays in a certain position instead of player B, or how the opponent actually got into their penalty area in the end and whether particular events could have been prevented, all by using comparative values (better player positions, faster skating values, different players, etc.) from training, from recovery (e.g. lack of physical fitness due to, for example, little sleep, high training intensities of the previous days, a cold from which the player has not yet fully recovered etc.) and from other games (from comparable situations).

From a labour law perspective, the employer may process employee data insofar as it falls within the scope of work-related matters or insofar as the data relates to the "suitability" of the employee "for the employment relationship or is necessary for the performance of the employment contract" (Art. 328b CO). As soon as data processing exceeds the scope specified by the employment relationship, this constitutes a violation of personality rights. As an employer, the sports organisation must therefore ask itself (even independently of an AI application) which of a player's data still falls within the scope of work-related data. Ultimately, however, a player's physical readiness and ability to perform is a decisive characteristic of their work performance. The data related to physical readiness and ability to perform clearly goes beyond that obtained during training and matches (and thus regular working hours), as sleep quality, other physical exertion as well as illnesses and injuries outside of regular work naturally have a direct impact on physical readiness and ability to perform during training and matches. This is not just about how to " extract" more performance from the athlete, but also about how injuries and over-exertion can be avoided, as they can often be very costly for the sports organisation as an employer, both in sporting and economic terms. In this respect, appropriate monitoring of this data is also in the interests of employees who, due to a lack of physical fitness and performance, could sustain injuries or otherwise suffer harmful health consequences if they are deployed inappropriately in training and matches. The employer, who issues instructions to the players (e.g. to participate in a match), also has a statutory duty of care in this context (see Art. 328 CO). The challenge is therefore not the principle of the use of such data, but the specific configuration against the background of the requirements of proportionality: What is really necessary, suitable and reasonable for the athlete with regard to the purpose? Who has access to the data? Is the data protected accordingly?

In any case, it can be argued in case 2 that it is the player who exports their own data on physical fitness and performance from their trackers and uploads it to the platform used by the sports organisation. This may constitute consent to the processing of their personal data, which in turn may justify a possible violation of personality rights within the meaning of Art. 31 Para. 1 FADP. However, such consent presupposes that they have actually been informed in sufficient detail about what is being done with their data and why, and who is receiving it - and they must act voluntarily, which may be questionable depending on the case. It is therefore worthwhile for a sports organisation in its role as employer to consider at an early stage whether the collection and analysis of data it intends to carry out is proportionate, whether it is made sufficiently transparent to the athlete, whether it is supported by the athlete and whether it is carried out for the athlete's benefit, so as not to undermine the voluntary nature of consent. Moreover, consent will often have to be given explicitly in order to be valid. The requirement is triggered either by the processing of particularly sensitive personal data (here: recordings from the athlete's private sphere) or by high-risk profiling (here: The AI predicts the athlete's work performance etc. [= profiling] and will sometimes lead to a profile that allows an assessment of key aspects of the athlete's personality and entails high risks for the person concerned if the analysis is an important basis for the decision on the person's sporting commitment). It is therefore mandatory to carry out a data protection impact assessment (DPIA) for such AI applications (Art. 22 FADP).

Finally, in addition to data protection, Art. 26 of Ordinance 3 of the Labour Act must also be observed, which prohibits behavioural monitoring for the (psychological) protection of employees - unless it serves to protect health, safety or performance and is proportionate. However, the rule only applies to monitoring "at the workplace" - for example on the pitch or during training; in this case, however, an employee is also "monitored" in their free time. Of course, it can also be argued in this respect that the athlete himself provides the data, but this also presupposes that he is offered the opportunity to switch off the monitoring in certain situations, for example, in the same way that the employee can switch off the GPS tracking of his company car during private use - so that it can be assumed to be voluntary. Whether they then do so is, of course, up to them.

With regard to the applicability of the GDPR and the EU AI Act, we refer to the explanations above. If the behaviour of an athlete is evaluated within the territory of the EEA, the GDPR may also apply in the present case constellation. The AI application also uses some biometric data and evaluates the performance of the players in the context of the employment relationship (or provides a basis for the coaches to decide whether to deploy them in training and matches). This constitutes high-risk AI systems within the meaning of the AI Act. Depending on the role (provider or deployer) and case constellation, the employer is subject to legal obligations (e.g. risk and quality management, data quality, conformity checks, documentation, EU representatives, reporting obligations, transparency obligations, etc.).

In the context of the AI Act, care must also be taken to ensure that an AI system is not used to analyze the athlete's emotional state or other emotions (is he annoyed or angry, resigned, etc.), as this is a practice prohibited under the AI Act in the workplace or educational environment; however, if it serves medical purposes or the athlete's safety, it could be justified, though.

Other typical use cases for sports organisations as employers

In general, there are hardly any factual limits to AI applications in the area of match analysis to identify patterns. For example, the following examples are already being used in practice, whereby an employer must also make the same legal considerations and take the same measures as described above:

- Applications that assess the influence of individual athletes and their decisions in competitions (especially in decisive and stressful situations) on the overall sporting result and create feedback that is broken down to the individual athlete, for the athlete, but also for the sports manager for their benefit (e.g. for deployment and team line-up decisions).

- Applications that assess the qualitative interaction of individual athletes in team sports so that a sports manager can determine the optimum line-up and strategy for a competition or match.

- Applications that utilise athlete data collected over many years during training and competition (e.g. heart rate, speeds, stress levels, intensity levels, body temperatures, breathing rates, blood pressure, oxygen saturation, etc.), but also outside of training and competition in some cases, to monitor recovery and general physical condition, enabling sports managers to better understand the strengths and weaknesses of individual athletes, improvement potential and fatigue and stress levels.

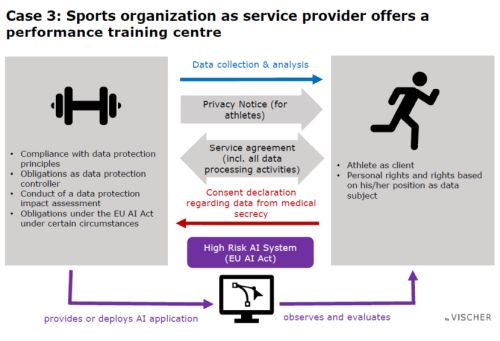

Case 3 – A service provider offers a performance centre

The most common service providers that have a direct contractual relationship with athletes and process their data are usually performance centres (organised under private law) and sports associations or teams that do not have an employment relationship with the athlete. In addition, athletes sometimes obtain services from providers who have technologies for individual aspects of sports performance to which they would otherwise not have access.

For our case 3, a performance centre based in Switzerland offers comprehensive services for the support of athletes (particularly in connection with fitness development and rehabilitation after injuries). Thanks to state-of-the-art equipment and technologies, the performance centre has access to all the data of a training device that an athlete is currently using. The athlete can use a badge to log on to each training station, whereby the performance centre then stores the number of repetitions, speeds and other training volumes, for example. The performance centre also knows the exact nutrients an athlete is consuming based on sensors under the measured food bowls in the buffet in the dining room and how the athlete is recovering from the stresses of training and competition based on 24/7 measurement of certain body data (using measuring devices such as sports watches from which the raw data can be exported). The performance centre uses an AI system to collate the large amounts of data, draw conclusions from them, point out certain exceptional values and create comparative and reference values among the athletes and make predictions, e.g. about an athlete's athletic potential. Precise monitoring of training data is also crucial, particularly in the case of medical rehabilitation after injuries carried out by performance centres, so that an athlete can regain their former strength as quickly as possible. The medical staff (doctors, physiotherapists) accompanying the athletes during rehabilitation are usually employed by the performance centre. However, the performance centre also cooperates with sports medicine institutes, which accompany an athlete in the training facilities of the performance centre.

The first question under data protection law here will be what role the performance centre has. As a rule, it will not be a so-called processor that merely processes the athlete's data on behalf of a responsible body and thus, in principle, only carries out what it is instructed to do. Rather, the performance centre itself will be the data controller because, firstly, it receives data from the data subject directly and has a contract with them for this purpose. Because the data subject can never be a controller with regard to their own data, the performance centre must perform this role and is therefore responsible for compliance with data protection. Secondly, the performance centre itself will have a significant influence on how the athlete's data is processed and must therefore (correctly) ensure that this processing complies with the FADP.

In the best case scenario, the performance centre will not need consent at all because it regulates the use in a contract. Although this also requires the athlete's consent, it is treated differently from classic consent in legal terms: The data processing is, as it were, the service. However, it will have to be described accordingly. The performance centre will not be able to dispense with requirements such as a privacy statement or a data protection impact assessment. If healthcare professionals bound by professional secrecy are involved, a declaration of consent must be available for the disclosure of data subject to patient confidentiality. The performance centre must therefore check what type of patient confidentiality data is to be passed on to any others caring for the athlete (e.g. fitness coaches, nutritionists, mental coaches, etc.). Such disclosure must be defined accordingly in the declaration of consent so that a further declaration of consent does not have to be obtained for each new disclosure.

The performance centre itself will in turn have to specify in its contract what the athlete's data may be used for, including the question of whether the athlete's data can be used, for example, for training the performance centre's AI applications. If this is not mandatory, the question arises as to whether athletes can nevertheless be forced to give their blanket consent to such use via their contract with the performance centre. Here, the case law is based on the connection between this use and the contractual service; there is no such strict prohibition on linking as there is in the GDPR, for example, under Swiss law, but a performance centre cannot simply choose to go as far as it likes. This also applies to disregarding other processing principles, such as the principle of proportionality. This aspect will have to be taken into account in the context of data collection, for example: should the athlete be given the choice of how far they want to "track" their lifestyle, or can they be expected to go "all or nothing" if they want to improve their performance with the help of AI. We assume the latter, even if in recent years there have been increasing paternalistic tendencies on the part of data protectionists with the aim of protecting a "weaker" party. Accordingly, they will make specifications regarding the organisation of data processing, i.e. demand measures to protect the athlete.

Such approaches are also pursued, for example, by the aforementioned EU AI Act, which can also apply outside of employment contract scenarios. In the present case, for example, where biometric data is collected and used to make predictions or categorisations regarding a person in the area of sensitive information (e.g. health), this may constitute a "high-risk" application that can trigger various additional requirements. If the setting for professional athletes is classified as "vocational training", this may also constitute a high-risk application, as various forms of AI-supported assessment of individuals are considered to be such in the education sector. Even if the performance centre is based in Switzerland, it would have to comply with the requirements of the AI Act - at least from an EU perspective - as soon as the output of the AI is also used in the EU as intended, for example because the performance centre provides its services to an athlete from the EU. If the performance centre offers its services directly to athletes in the EEA, the GDPR pursuant to Art. 3 para. 2(a) also applies in the context of this targeting of private individuals. This can have consequences: As soon as health data is processed, explicit consent will regularly be required, which must also be able to be withdrawn at any time, even if a contract with the athlete provides for the processing of such data (Art. 9 GDPR).

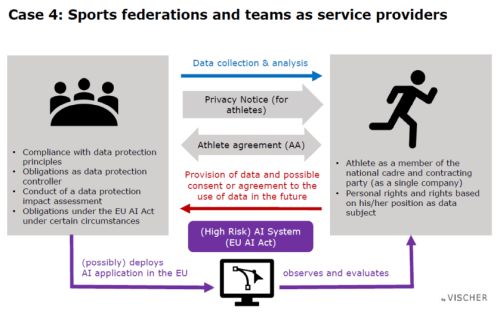

Case 4 – Sports associations and teams act as service providers

In case 4, a national sports federation based in Switzerland has undertaken to provide comprehensive support and organisation of training and competitions as part of an athlete contract concluded with the athletes belonging to it. In return, the athlete undertakes to participate in training and competitions and must also sign this athlete contract in order to be allowed to practise their sport professionally, because membership of a national sports federation is a mandatory requirement for eligibility to participate in international events.

The details of the organisation of these training sessions and competitions (e.g. the technologies used or the use of data) are not regulated in this athletes' contract. The national sports federation has access to numerous athletes' training and competition data, data relating to equipment and, in some cases, health data (sports medicine tests and data from injuries). It processes this data via a central athlete platform, via which an athlete has access to all their data and can also grant certain access authorisations to others - e.g. coaches, equipment service staff, physiotherapists, sports scientists, their doctors or those of the federation). An AI application supports both the federation officials and the athletes themselves in analysing and assessing data and makes appropriate recommendations. For example, the AI application can predict an athlete's perception of exertion for planned training sessions. This is done on the basis of measured amounts of training paired with the athlete's health and performance data and their perceived (and correspondingly logged) exertion. This enables athletes and their trainers and coaches in the national sports association to optimise, control and, in particular, plan the design, effect and analysis of training more precisely.

A sports federation whose athletes are not employed (as is usual in individual sports) must ensure that the obligations arising from the athlete contract are not too extensive. This is particularly the case if an athlete is not allowed to exercise their profession without belonging to an association because they would otherwise not receive a licence to participate in international competitions. In this case, the support of the athlete is part of the obligation under the athlete contract. This includes the processing of data. As mentioned in case 3, the obligations in connection with data processing may not simply go as far as desired. For example, the national sports federation is dependent on the disclosure and processing of certain athlete data in order to fulfil its contractual obligations (e.g. to organise travel). However, the processing of certain sensitive data (e.g. health and 24/7 performance data) would regularly go beyond the scope of necessary data processing and the statutory performance mandate of a national sports federation, especially as the athlete in individual sport is ultimately responsible for their own performance and the voluntary nature of signing an athlete contract with regard to certain clauses can sometimes be questioned in cases of doubt due to the strong position of a national sports federation. In our opinion, a blanket obligation to disclose particularly sensitive data such as health or 24/7 performance data would therefore be disproportionate in the present case; if the GDPR applies (for example, because the athlete's behaviour is also monitored in the EEA or the service is offered there as intended in order to also address athletes in the EEA), it must be expected that the additional consent required for the processing of health data, even within the framework of a contract, will be considered invalid due to a lack of voluntary consent. In practice, a graduated approach is therefore recommended, i.e. it is left to the athlete to decide how far they wish to go with regard to the provision of their data - after providing appropriate information. If they want to provide all of their data so that it can be analysed for the specified purposes using AI, they should be able to do so. Depending on whether only the FADP or also the GDPR applies, the sports association will have to make provision for data processing that has already taken place to be stopped again (as consent can be withdrawn at any time under the GDPR, whereas this can be regulated more restrictively under the FADP). The sports association will also not be able to avoid a data protection impact assessment; this is expressly provided for in case 4 because extensive processing of particularly sensitive personal data will regularly be involved (see Art. 22 Para. 1 and 2 FADP). It must also be assessed on a case-by-case basis and with regard to the functionality of a specific AI application to what extent athlete data once fed into an AI application can also be used after the termination of the athlete contract, whereby an agreement with the athlete would also be advantageous in this context. This also applies to the use of athlete data for the further development of the company's own AI models, which will regularly be a requirement in order to benefit from the knowledge gained from working with individual athletes.

Depending on the scenario and contractual services, reference should also be made to the explanations in case 3.

A national sports federation based in Switzerland is generally not subject to the AI Act. However, if it also looks after athletes in the EU or supplies their coaches in the EU with AI output such as the analysis generated by an AI for use in the EU as intended, it may also apply to the sports federation. Although the use of systems to classify individuals based on biometric characteristics may be covered as an applicable case, as long as there is no high-risk AI system, there are by and large only transparency obligations. The athlete would therefore also have to be informed in accordance with the AI Act, but this will not cause any difficulties. However, if the assessment of an athlete takes place in a context that can be described as "vocational training", this again constitutes a high-risk AI system with correspondingly extended obligations. Therefore, before using AI systems, it should be clarified whether special legal obligations apply.

Further applications from providers of specific services

Specific AI applications that offer specific solutions and are helpful for elite sport are increasingly appearing on the market. For example, there are fully autonomous bike fitting systems that allow cyclists to optimise the settings on their bike in terms of comfort, based on physical mass and biomechanical principles in the shortest possible time and which make AI-based suggestions to the cyclists. Other applications predict the effects of certain loads on an athlete's musculoskeletal system or support the athlete in analysing correct movement patterns when resuming training after an injury, in which the system can provide direct feedback to the athlete. Still other applications have focused on the technical metrics of specific sports, for example by analysing the golf swing (i.e. all movement characteristics and forces) and providing the athlete with AI-supported feedback and suggestions to improve technique. Another specific application for processing data from snow sports is, for example, analysing external factors when deciding which ski wax to use for a cross-country skiing competition (taking into account factors such as temperatures, humidity, snow granularity, fresh snow, old snow, artificial snow, etc.). Based on the data collected, AI can recommend the optimum wax product (with a certain probability) for an athlete's skis.

In such applications, athletes receive the specific services of these providers in return for compensation (or possibly also in return for certain personal advertising rights of the athlete) and are normally subject to the general terms and conditions (including terms of use) of the provider. The provider must inform the athletes about the collection and processing of their data as part of a data protection declaration, fulfil the other obligations under data protection law (such as data protection impact assessments) and, as explained above, obtain the athlete's consent for this under certain circumstances; as a rule, the service provider will be an independent controller and not merely a processor. If the service provider also provides its services to athletes in the EEA, it will also be subject to the GDPR in this respect. Whether such a service provider also falls under the AI Act must be examined in each specific scenario, in particular determining the place of marketing, provision and use of the AI application and its output. If it provides its customers with AI functions as a service, it can easily also be considered a provider of corresponding AI systems and not just their user. As systems for biometric categorisation can also be considered high-risk AI systems, this can give rise to a number of additional obligations.

AI as support for field-of-play decisions

If sports organisations act as rule-makers and are therefore responsible for ensuring that sporting events are conducted in accordance with the rules, it is obvious that a key area of application lies in the "field of play". International sports federations and sports leagues are examining AI applications, particularly to support or replace referees, or are already using such technologies. Tennis, for example, has been utilising AI for more than a dozen years to determine whether a ball has landed "in" or "out" of the court line. AI is also omnipresent on the football field of play. In automated offside technologies and goal-line technologies, in addition to collected data points on the players' bodies and in the ball, AI also helps to make offside and goal decisions even faster and more precisely.

From a data protection perspective, the first step is to check whether and to what extent personal data is processed. In many applications, this will involve the images of athletes during the competition, which a sports organisation uses exclusively for the purpose of enforcing sports rules, for evidence purposes and for learning purposes for an AI system. This data processing will normally not be limited to Switzerland, even if an international sports federation as rule-maker is based in Switzerland, but will instead take place all over the world (because the subordinate foreign sports federations, leagues and organisers often have to use certain technologies as determined by the international sports federation). In addition to complying with the general data processing principles, an international sports federation must provide appropriate information about the data processing, limit the processing in terms of subject matter, personnel and time and - depending on the data protection law - ensure a legal basis for the processing. Depending on the structure of the relationship between the international sports federation as the regulator and the national sports federations, leagues and event organisers, the international sports federation will not be solely responsible from a data protection perspective - or not at all - but rather these national sports organisations. However, this must be examined on a case-by-case basis and the further measures required under data protection law, such as contracts on joint responsibility, data export contracts and data protection impact assessments, must be determined. You will also need to prepare for the event that an athlete asserts their data subject rights, even if this will rarely be the case. If automated individual decisions are made, which is generally avoided (the AI is only used to prepare or support corresponding decisions, which are ultimately made by a human), additional hurdles such as the requirement for a complaints procedure must be overcome.

From a sports regulatory perspective, the use of AI applications on the field of play may require an adaptation of the applicable competition rules of an international sports federation or sports league and, in many cases, additional information. This is usually the responsibility of the respective board (or other delegated bodies, the general assembly or committees depending on the organisational structure of an international sports federation or sports league). If such a sports organisation simultaneously (co-)develops a corresponding AI system (itself or on behalf of others) and, for example, obliges other subordinate sports organisations (such as national sports federations or national sports leagues) in the EU to use the corresponding systems, these international sports organisations could be subject to obligations under the AI Act, even if they are based in Switzerland. This raises the interesting question of whether high-risk AI systems can also be assumed if such systems are used to assess athletes on the playing field as their "workplace", but this is not done directly by their employers, but by organisations associated with them. The same applies to sports jurisdiction proceedings, as the AI Act also subjects the use of AI systems in courts to certain regulations.

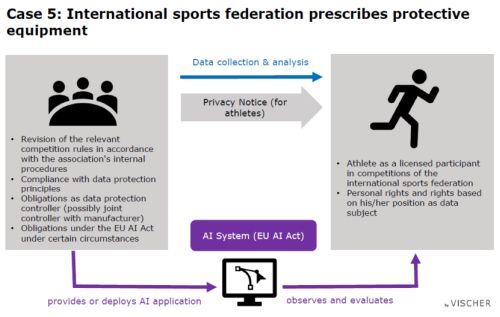

Case 5 – An international association prescribes protective equipment

In case 5, a sports equipment manufacturer (based in Germany) has spent years working on a new airbag for a specific type of action sport. The airbag is now ready and, thanks to the comprehensive training of the AI component of its software, is also able to trigger the airbag at the right time and to protect an athlete in an extreme situation. This airbag is therefore always able to recognise when it is a "normal" extreme situation (e.g. when the athlete jumps in the left direction in the air and gets into a deliberate tilt or when he is literally shaken by strong impacts due to the bumpy surface and also grazes the ground, for example) and when there is actually a dangerous situation that makes it necessary to deploy the airbag. The international sports federation responsible for this action sport (based in Switzerland) is very pleased with this development and is making it compulsory for all its athletes to wear an airbag at international competitions. However, the manufacturer is currently the only supplier that can offer such an airbag. In addition, all athletes are obliged to hand over the airbag to the international sports federation in the event of a deployment so that it can analyse the relevant data and continue to train the AI in cooperation with the manufacturer (the athletes receive a new airbag in return).

Although personal data is processed when the international sports federation or the manufacturer obtains the relevant data for the purpose of analysing it after the airbag has been deployed, the scope of this personal data is limited (insofar as the personal data in this case is limited to the technical data attributable to an individual athlete during the competition performance, such as speeds, torques, force exerted and the like, and no physical data is recorded, for example). In addition, this data processing is carried out to protect all athletes from injury, from which it can be argued that, if necessary at all, both under the FADP and the GDPR, the overriding or legitimate interests of third parties (i.e. the health protection of all athletes participating in the competition).

Even if this depends on the specific form of their cooperation, the international sports federation and the manufacturer will typically be jointly responsible for the resulting data processing. Accordingly, they must comply with all data protection obligations associated with this role. In this case 5, the international sports federation is already at least jointly responsible in the sense of data protection law because it stipulates who has to wear the airbag to protect against injuries and when, and thus becomes the data subject from whom data is collected in the event of triggering (this would be different if the international sports federation only enables the wearing of an airbag and declares certain airbag products to be usable after a quality check; then the athletes decide to whom they want to entrust their data). The international sports federation thus determines both the purpose and the means of data processing (at least to a significant extent). As joint controllers, both the manufacturer and the international sports federation must provide appropriate information about the data processing and enable the exercise of data subjects' rights. From a data protection perspective, it is advisable to structure the relationship between the international sports federation and the manufacturer in individual cases in such a way that the data protection obligations are sensibly divided according to their competences and roles in the organisation within the action sport in case 5 and the necessary documentation is created. The GDPR even expressly prescribes a joint controller agreement for such cases.

In terms of sports regulations, the introduction of such obligations in connection with the equipment normally requires an amendment to the relevant regulations (e.g. the competition regulations). This amendment must be made in accordance with the internal responsibilities and procedures of the federation.

In this case 5, the international sports federation must also check whether it falls under the EU AI Act. This is somewhat tricky as the first question is whether the airbags would be considered a high-risk AI system due to the pressurised containers they have and that their discharge is controlled by AI, as AI safety components of products covered by Directive 2014/68/EU may lead to this qualification under certain circumstances. This would have corresponding consequences for the sports equipment manufacturer, but also for those who import, distribute or use these products, provided they also fall under the EU AI Act. Whether this would also affect the international sports federation would have to be examined (see Part 7 of the blog series on the AI Act).

Other typical use cases with sports organisations as regulators and supervisors

AI will also play a role in preventing injuries in other ways in some events regulated by international sports federations and sports leagues in the future. One example of this is the rapid identification of concussions, which are very common in many sports. AI applications already exist that can immediately determine whether the data subject has the characteristic features of a concussion by measuring pupil dilation when exposed to light after falls or blows. International sports federations could make such AI applications mandatory for on-site medical staff at their events, to improve the protection and health of athletes (in particular to prevent even worse physical damage in the event of non-detection). Doping authorities are currently examining the use of AI applications to analyse huge amounts of data or to quantify the risk of doping in certain situations (e.g. in the case of certain injuries, after particular drops in performance on stages of cycling tours, etc.). The TV rights holders of sporting events are already using systems that automate the camera work as part of the TV production with the help of AI and create highlight clips based on the reactions of viewers to certain situations at an event that are recognised by AI applications (automatically generated highlight clips).

The use of athlete data for other purposes

It is foreseeable that athlete data will increasingly be used in the future for purposes other than those arising directly from the performance relationship between the sports organisation and the athlete (and thus to improve the athlete's performance). For example, it is conceivable that data from previous athletes with a comparable physical constitution could be used to improve the performance of new, young athletes. AI applications have the potential to continually perfect the entire training programme for new generations of athletes based on new inputs with new results from training and competition. Of course, athlete data can also be used for commercial purposes. What recreational basketball player wouldn't like it if, as part of an AI-based app that analyses various movements from the recreational athlete's basketball, the avatar of their favourite professional basketball player gave feedback on their movements, improved them and also encouraged them to keep going?

What such application examples particularly have in common is the time component. A sports organisation must take legal precautions to secure the athlete's data for such purposes beyond the end of the athlete's career. Under the FADP, it is permissible to refrain from deleting personal data in the future on the basis of overriding interests or the consent of the data subject (Art. 30 para. 2(b) FADP in conjunction with Art. 31 para. 1 FADP), in particular if a sports organisation takes technical measures to ensure that personal data no longer appears in the output of an AI application (as would be a feasible option, for example, when using older athlete data to improve the performance of young athletes with similar qualifications; ultimately, it is not necessary to draw conclusions about the identity of the former athlete for this purpose). Here, the FADP with the justification ground of non-personal processing (Art. 31 para. 2(e) FADP) can be helpful for the development of corresponding AI applications; it tends to offer more freedoms than the GDPR, which in turn can give Switzerland a locational advantage.

For the use of the voice or (moving) images (also for avatars generated on the basis of images) for commercial purposes, it is always advisable to conclude an agreement with the athlete concerned. This is usually limited in time and defines a framework within which certain "exploitable" personal rights may be used. It is often agreed that the individual realisations require the approval of the athlete or their manager, whereby they may not refuse approval in bad faith. However, the establishment of such a framework is also in the interests of the sports organisation. Art. 27 para. 2 of the Swiss Civil Code prohibits excessive obligations for the protection of the data subjects, which means that a contract with excessive provisions on the commercial use of personal rights (e.g. the use of an athlete's images for commercial purposes during their lifetime) would be null and void. Here, too, Swiss law tends to offer more legal certainty: even in data protection, consent in a commercial context under the FADP can certainly be designed in such a way that it cannot be revoked without corresponding financial consequences for the data subjects; this is barely possible under the GDPR.

Concluding remarks

Irrespective of the use cases discussed above and their legal assessment, every sports organisation and every company outside the world of sport will have to deal intensively with the use of AI and regulate this use. If this has not already been done, it must always be done in accordance with the organisation's own ethical principles. We have developed the "11 principles" for our clients, which we have already presented in Part 3 of our series and which serve as a basis for the guidelines a company wants to develop for itself in order to regulate the use of AI for the matter itself and organisationally. Building on this, we recommend defining the tasks, responsibilities and general compliance processes as part of an AI directive. Part 5 of our series offers an exemplary step-by-step approach. Finally, companies must also protect themselves against new forms of attacks by malicious actors on AI applications (see part 6 of our series).

Although AI has enormous application potential in sport, those involved in the sporting world largely agree that AI will not replace humans, but rather support them. Ultimately, it is often not just the objective and raw data that is decisive for success in top-class sport, but also the barely measurable human component (e.g. the extent to which a captain of a football team is able to pull his team-mates along for a chase or get them out of a performance slump, or the extent to which certain individual athletes can cause unrest or calm in a team). Also, despite all the technological possibilities, it should not be forgotten that the presence of a human referee has a certain psychological component. Neither a bot nor a robot is able to resolve disputes between (human) athletes in competition in the heat of battle. In addition, a (human) contact person or authority is also helpful in other scenarios, not least to resolve unforeseen or extraordinary scenarios with the necessary human intuition (e.g. when dealing with disruptive spectators, to avoid obvious errors in the systems, in the event of extraordinary decisions, injuries to athletes on the field of play, for management in the event of power cuts or other breakdowns, etc.). Such AI-supported decisions, judgements and applications therefore contribute above all to the more precise enforcement of the rules, to the sharper and more objective evaluation of performance data or to the comprehensive protection of athletes' health and thus primarily serve to support the referee, the sports manager or the athlete.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.