Foreword

This sixth edition of Africa Insights delves into the phenomenon of African urbanisation and the unique nature of cities on this continent.

The conventional view is that African cities are in a crisis precipitated by a relentless influx of people into urban areas, overstretched basic services, fragmented planning and the legacy of colonial-era spatial planning, among other things.

Our research partners at Stellenbosch University's Centre for Complex Systems in Transition highlight the difficulties facing most African cities, which the COVID-19 pandemic has so ruthlessly exposed. But they also see opportunity on the other side of the coin.

This opportunity lies in the potential for new and transformative city systems specifically suited to urban Africa. This opportunity can best be seized by investing in smarter urban infrastructure and 4IR technologies, establishing dedicated funding for the upscaling of urban technology, and implementing policies that address land use mismanagement and fragmented development.

The researchers believe that it will also be helpful to reform and enforce urban regulations, strengthen urban governance and, interestingly enough, take advantage of the inherent dynamism of the informal sector.

Informality is usually considered a drawback, and the researchers acknowledge that the overreliance on informal sector employment, for example, exacerbates the vulnerability of African cities and their inhabitants.

At the same time, they point out that urban informality can provide cities with resilience and agility. Informal networks within Africa's urban areas understand the local context, are constantly innovating and have existing relationships that enable them to deliver appropriate services - from mobile payment systems to taxi services. Thus, governments should learn to be responsive to, and supportive of, the informal sector.

Another interesting idea is that eco cities, also known as smart cities, might offer tantalising visions of the future but will probably remain out of the reach of the majority of African urbanites, especially the urban poor.

In a continent as diverse as Africa, there really is no one-size-fits-all approach and the best urban development strategies are based on localised data within specific contexts. The deeper the understanding of local context and conditions on the ground, the greater the prospects of building cities that are affordable, liveable, economically productive and sustainable.

Considering that Africa is the most rapidly urbanising continent in the world and that 50% of Africans will be living in urban areas by 2035, this may well be one of the most compelling editions of Africa Insights yet.

Robert Legh

Chairman and Senior Partner

Introduction

Cities have become the epicentres of the COVID-19 crisis, with UN-Habitat estimating that 95% of all cases worldwide are located within urban areas.

African cities are particularly vulnerable as they face an added and uniquely African challenge stemming from the nature and quality of urbanisation on the continent.

Unlike their Northern counterparts, African cities are historically splintered without a legacy of inclusive urbanism or widespread, networked infrastructure. This leaves most inhabitants unable to rely on the state to meet their basic needs.

Planned and appropriately managed urban development has not kept pace with the realities of the rapid urbanisation taking place in African cities, seen in numerous informal settlements, a lack of access to basic services and infrastructure, persistent and outsized reliance on the informal sector for employment, high population density, and overcrowded public transport and marketplaces.

Superimposing the COVID-19 pandemic on these already strained systems 'has brought into sharp relief some of the fundamental inequalities at the heart of our towns and cities', notes the head of UN-Habitat, Maimunah Mohd Sharif.

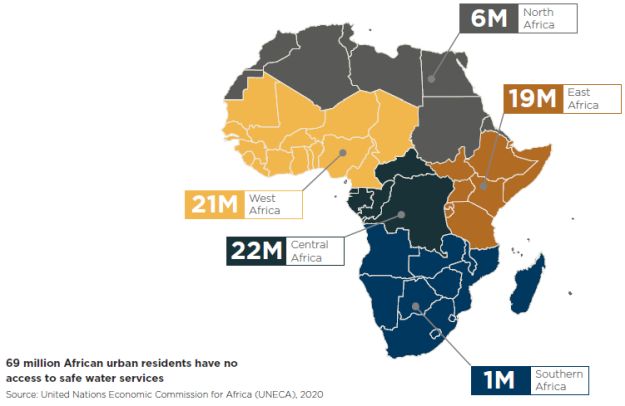

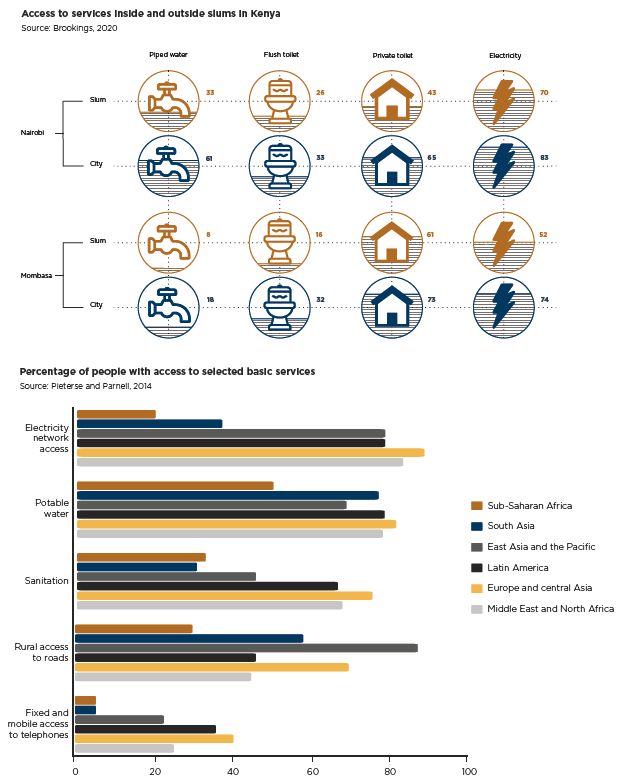

Urban residents are already at a disadvantage: only 55% of urban residents across Africa have access to basic sanitation and 47% to handwashing facilities. As seen in the map on page 4, large swathes of the population lack access to safe water, which leaves them unable to practise preventive care against COVID-19. Access to healthcare products and services is limited by low ratios of healthcare professionals and hospital beds and the dominance of global supply chains for medicine and pharmaceuticals.

Almost 86% of urban residents are in the informal sector, making them particularly vulnerable to lockdown, self-quarantine or isolation and unable to rely on social protection, mechanisms of support or alternative incomes. According to UNECA, the loss of income has a cascading effect on food security and housing needs. With approximately 70% of urban inhabitants across Africa renting their accommodation, job losses are tightly coupled to increased risks of eviction and homelessness. A survey of five informal settlements in Nairobi revealed that COVID-19 had already caused the 'complete or partial loss' of income as of 22 April 2020.

Urban areas are the meeting point of multiple systems: infrastructure, the economy, housing and food systems all coalesce around the idea of the city. History has shown that cities have the potential to be force multipliers of transformative change. However, COVID-19 has clearly revealed that the specific characteristics of African urbanisation have instead exacerbated the vulnerability of cities to the impacts of pandemics and potential future disasters.

Urbanisation on the African continent has its roots in historical patterns and this, coupled with the developmental constraints imposed by climate change, has particular implications for the future of African cities.

Hidden within the crises of African cities are the potential benefits of informality and investment opportunities. Other important factors to consider are urban governance and its role in policy development and spatial planning, as well as the possibilities for community-directed solutions.

Patterns of urbanisation in Africa

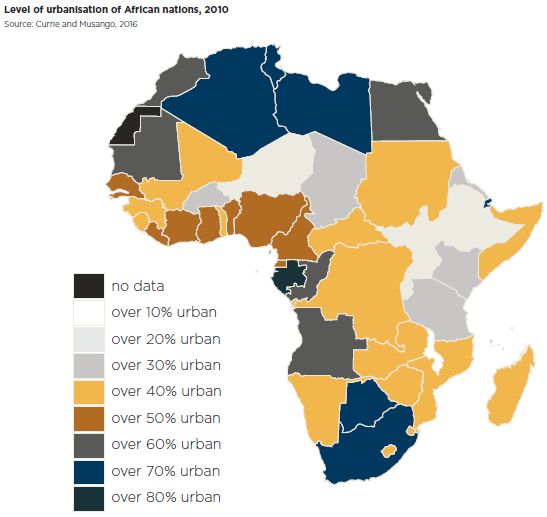

Africa is the most rapidly urbanising continent, and starting from its base as the least urbanised continent currently, has massive potential for growth as seen in the map below. Cities are expected to have approximately 1.5 billion urban residents by 2050, most of them young.

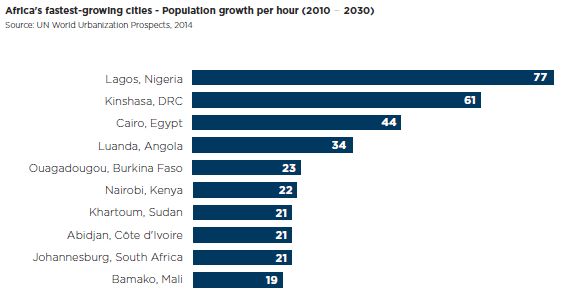

It is expected that Africa's population will be 50% urban by 2035, with most of this growth expected to occur in slums or informal settlements. To put Africa's population boom into perspective, Lagos, projected to be the largest city in the world by 2100, is expected to experience population growth of 77 people every hour between now and 2030.

The graph below shows the population boom for some of the other fastest-growing African cities after Lagos.

This explosive growth could be a potential opportunity in its young, growing population, but presents an equally threatening alternative if unemployment, current infrastructure gaps and service delivery deficits remain a problem.

African urbanisation has thus far been characterised by poverty and inequality, informality in governance and the absence of a strong local state with a clear and unchallenged mandate to manage the city. The average urban inhabitant of African cities experiences structural poverty and systemic exclusion, even within African cities with comparatively high standards of service and high average incomes, such as Johannesburg, Accra or Gaborone.

Shortfalls of urban infrastructure, lack of urban planning, disorganised land use, regulatory blockages and vested interests have created sprawling, fragmented and hyper-informal cities. The experience of informal settlements is increasingly the reality of African urban inhabitants. UN-Habitat estimates that about 47% of Africa's urban population (roughly translated to 257 million urban residents) lived in slums or informal settlements in 2019.

The first graph overleaf indicates the parallel and contrary experiences of Kenya's city and slum inhabitants when it comes to access to basic services, while the second graph compares the varying levels of access to basic services across worldwide regions.

Access to basic sanitation and potable water, garbage collection, stable and affordable electricity and public transport will continue to be a problem for urban inhabitants owing to systemic shortfalls due to a lack of planning and management, as well as pressure on already strained service-delivery mechanisms. This has led to the formation of 'pirate cities' where inhabitants rely on pirate operators.

Rapid urbanisation requires emerging and fast-growing cities to make choices about managing their growth and shaping their urban density, particularly if sustainability is to be a consideration. Choices made today will ensure economic benefits or costs for the coming decades.

A sustainable vision of densified cities would include compact urban growth structured spatially to ensure highly accessible cities, relatively high densities and widespread networks with mass transport that is both affordable and on time.

Neighbourhoods would be liveable, functional and socially mixed, with varied housing types for different income brackets, nearby job opportunities, and soft mobility driving dense and connected grids of streets.

By contrast, unplanned cities result in uncontrolled sprawling growth with scattered networks that indicate an inefficient pattern of urbanisation.

The value of spatial planning and efficiently distributing both human and job densities is in their ability to make resource consumption more efficient. Without the required urban planning expertise, however, urban growth will continue to be unplanned, unmanaged and fragmented.

Cities and climate change

Growing cities mean increased demand for resources: building material, food, energy and water. However, unlike their Global North counterparts, African cities find themselves growing on the cusp of a global climate crisis set to disproportionately affect the African region (and urban areas in particular), which is warming up at 1.5 times the global average. As cities already consume 75% of natural resources, they become the battleground for global climate crisis interventions.

Development of cities in the face of planetary limits to growth is driven by research and policy in two areas: mitigation, requiring resource efficiency or limitation, and adaptation, requiring building the capacity of people to adapt to changing climate conditions.

Development of urban areas across the African continent, besides contending with deficits in basic services such as education, healthcare and employment, is now tightly bound to concerns of sustainable practices, resource scarcity and a keen understanding of the ecological limits to growth. The Cape Town water crisis from 2015 to 2018 foreshadows what African cities can expect of the future if the goal of sustainable development is not taken seriously. The aim now is to find a balance between protecting the environment, encouraging economic growth and relieving social equity pressures.

Considering their different development contexts, cities of the Global South face different needs and pressures from those faced by the Global North; however, the urban planning approaches used do not reflect this. Urban planning practices remain chiefly influenced by approaches developed in other parts of the world for other, very specific urban contexts. In the absence of specific, empirical data documenting urbanisation trends across Africa, and the overwhelming number and variety of social problems, there is a reliance on generalisations informed by ideas of urbanisation, economic growth and sustainability from the Global North. These do not fit the African context.

One method of development for African cities is usually hailed as eco or smart cities, where parts are redesigned to reflect the Global North's image of modernity and sustainability. Such development is criticised as reinforcing splintered urbanism that effectively excludes the poor. Eco cities are master-planned new urban areas powered by green technologies, typically characterised by higher density of population, housing and connections to employment by a public transport network.

Eco cities attempt to balance environmental, economic and social benefits while also ensuring resilience in the face of future challenges. Examples of smart cities across the continent include Nigeria's Eko Atlantic City, Kenya's Tatu City and Rwanda's Vision City. While these cities offer tantalising visions of the future, they are both unaffordable and exclude the majority of African residents.

The development of strategies to establish African cities that are equitable, liveable and economically productive will only be possible if informed by localised data, specific to the varying contexts on the African continent.

The United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) has said that to address global sustainability, a key requirement is uncoupling a city's resources from its effects, allowing for less environmental impact per tonne of materials consumed.

A conceptual tool that would enable African cities to determine their own resource requirements is urban metabolism. Urban metabolism has been defined as the sum total of the technical and socioeconomic processes that occur in cities, resulting in growth, production, energy use and the elimination of waste. It is based on the idea that a city's metabolism can be influenced by making small changes to its systems.

Taking this industrial ecology perspective balances the needs of the present while still considering those of the future. Strategies for sustainable cities include understanding their resource flows, grouping cities according to their circumstances, and adapting practices and formulating recommendations (informed by successful local sustainability initiatives) suited to their grouping.

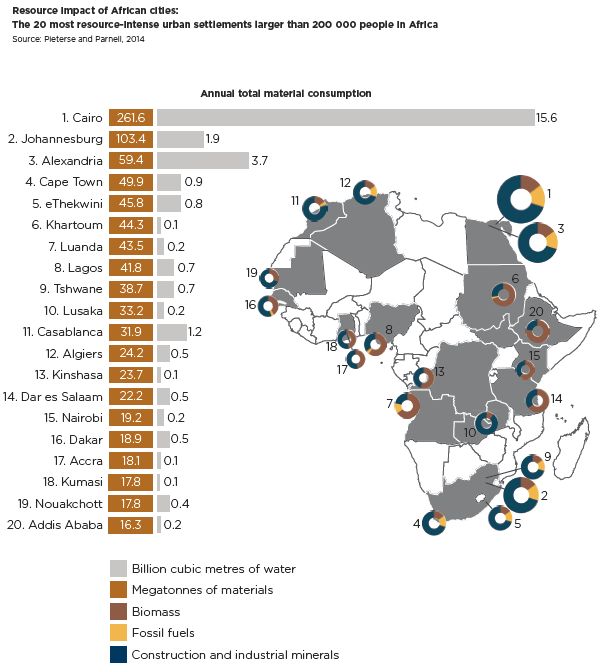

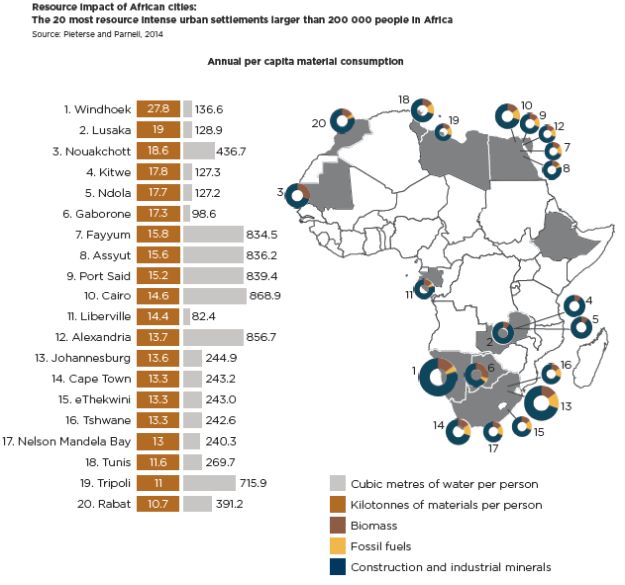

The following diagrams show the resource type and intensity for African cities in 2010. The map on this page displays total annual material consumption, while the map overleaf gives annual per capita material consumption.

When considering the cities displayed in these maps, there are three categories of interest, with their respective strategic approaches:

- Cities found on both maps tend to have a higher per capita GDP, higher human development index (HDI) ratings and lower prevalence of informal cities. These cities, located mostly in Northern and Southern Africa, include Cairo, Lusaka and Johannesburg, and might benefit from strategies to encourage maximal output from their resources.

- Cities missing from the map below could benefit from prioritising improvements to their access to resources, and can expect increasing resource intensities as they become more industrialised. An example is Lagos which, compared to a city such as Windhoek, is not a high per capita consumer owing to its large population.

- Africa's fastest-growing cities are missing from both maps. These cities are mostly from East and West Africa such as Ouagadougou in Burkina Faso and are where resource intensity is expected to grow in the future.

The lack of formalised infrastructure systems in African cities introduces an opportunity. With new understanding for the requirements of African cities comes the potential of new systems shaped along novel paths specifically suited to the urban context of the Global South.

Crisis as opportunity in cities

Urbanisation has, historically, been a force for change and transformation. This is due to its close link with economic growth, innovation, structural transformation and the improvement of individual well-being as a result of increased production, growth and access to jobs.

However, the informality of systems in African cities leads to vulnerable living conditions and employment for a large portion of the urban poor, along with a contracted tax base for governments.

Urban planners attempt to design away crises. Governments attempt to enact legislation, policies and plans to undo the urban legacies of fragmentation as large numbers of stakeholders with limited power and conflicting interests attempt to engage one another.

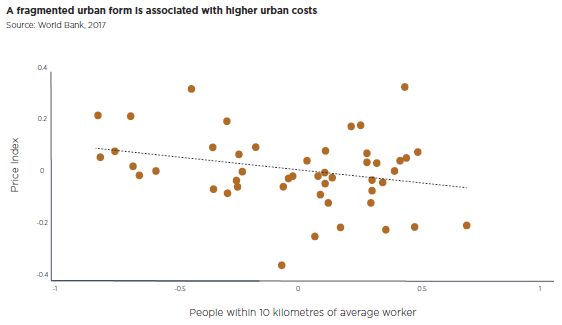

Fragmentation manifests as a lack of widespread, networked infrastructure, resulting in socioeconomic exclusion. This in turn results in higher patterns of expenditure for urban families in Africa.

South Africa under apartheid was an example of cities being subjected to reinforced spatial inequality. Today, regardless of the good intentions of both urban planners and government, it appears little progress has been made in narrowing the gaps, trapping many African cities in their colonial forms.

Choosing to view these urban crises as an opportunity is a means to undo the legacies of urban segregation and fragmentation. A renewed political and public sphere grounded in redistributive discourses can encourage alternative ideas for locally specific urban areas and allow new knowledge and passion for the future integrated city to emerge. What is needed is a concerted effort to harness progressive organic catalysts that work at the margins of mainstream politics to trigger change. Describing African cities as 'works in progress' acknowledges their complexity, fluidity in their adaptability and breadth of diversity.

Unable to depend on the state for consistent basic services and infrastructure, urban residents rely on informal private providers for most urban services such as energy, water, housing, public security, telecoms and waste management.

Examples are local waste collectors in Addis Ababa working with a waste-to-energy facility, the minibus taxi industry in South Africa, boda-boda motorcycle taxis in Uganda and grand taxis in Morocco. These solutions are driven by ordinary citizens who become agents of the change they wish to manifest, resulting in valuable development because it is specific to the challenges of the local context.

Emergent properties of cities are encouraged by the informality found in most African cities. Rather than giving rise to linear development, informality supports a circular approach of continuous engagement with different concepts and ideas in residents' daily experiences. Isolation, or a lack of state assistance, can lead to an autonomous space where new actors may emerge with dynamic and creative solutions, usually subversive of the status quo.

While flaws do exist, urban informality provides cities with resilience and agility, leaving urban planners the task of encouraging the benefits of informality. According to the WEF, informality is responsive to demand, job creation and self-sufficiency, while also exhibiting the negative traits of high costs and inefficiencies, low-quality services, and unsafe and unfair labour conditions. Governments should learn to embrace informality by being aware of these local, catalytic changes and seeking to respond and support them, instead of imposing their own ideas.

Formalising the informal sector must include a clear understanding of the context, two-way communication with informal actors and a path of formalisation dependent and varied enough to cater to the specific group involved. Such support would aim for non-exploitative relationships with the formal economy, regulatory controls to ensure informal actors are not excluded, and encouraging access to basic financial services and networks that assist informal businesses in becoming financially secure.

A part of how African cities can accomplish this is through localising technology, making use of smart infrastructure and taking advantage of the opportunities inherent in the dynamism of the informal sector.

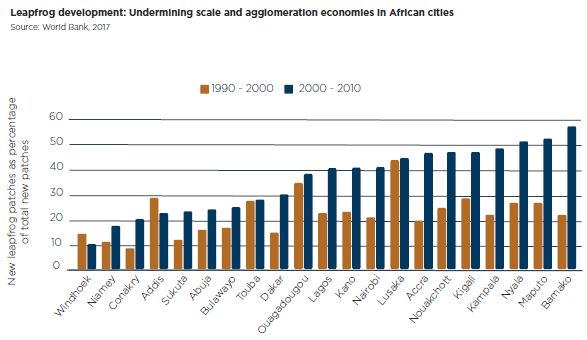

A potential revolution in African urban living could come about by leveraging the advantages of leapfrogging technologies (as we have seen with the penetration of mobile telephones across the continent), technological innovations in energy (solar photovoltaic systems and battery storage), and the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR). The graph below shows how African cities are leapfrogging technologies.

Bridging the infrastructure gap within African cities will require accelerated investment in smarter urban infrastructure. Examples are Upande, which uses internet of things (IoT) infrastructure to manage Kenya's water delivery and leakages within its system, and Uganda's CSquared, which lays fibre optic cables across major African cities.

Smarter urban infrastructure will also enable data collection to drive smarter investment decision-making, prioritising efficient and effective investments to support the urban poor.

Exciting technological solutions that tackle urban challenges are poised for scale in Africa. However, the continent does not have any dedicated funds for scaling urban technology.

Investment in the 4IR has substantial potential as a transformative tool for the continent. The ICT sector has already encouraged economic growth and structural transformation. Mobile technologies and services alone have contributed 1.7 million jobs within both the formal and informal sectors, according to the Brookings Institution. 4IR has allowed African labour forces to reinvent their skills and production, while also increasing the accessibility of financial services and investment, modernising agriculture and agro-industries, and improving healthcare and human capital. Failing to capitalise on 4IR opportunities will exacerbate the global 'digital divide' and lower Africa's global competitiveness.

Finally, investment in Africa's research ecosystem to incubate local innovations will help shape urban planning decisions, closing the loop in terms of Africa driving its own development.

Urban governance

African governments continue to lag in their response to the current urban revolution, hindered by a lack of financial capacity that would allow a more equitable pattern of investment. So far, policy responses to the urban boom have been mostly relegated to local decision-making or confined to sectors such as housing, electricity or water.

According to UNECA, policy responses need to be guided by a strategic national-level vision of urbanisation that will encourage structural transformation.

The structural transformative power of cities is dependent on urbanisation with industrialisation. Cities bring about growing and changing patterns of consumption, creating opportunities for domestic manufacturing. Better-functioning cities and systems of cities are also beneficial for industrial development. Improving urban productivity and economic development will properly focus the enormous wealth African cities already create.

Key opportunities within the urbanisation-industrialisation nexus include urban demand as a driver of industrial development. Processed and manufactured goods, food and housing are growing and changing, stimulating the possibility of diverse and connected systems that could precipitate system-level change, while the agglomeration of economies could act as city-level enablers. Policy priorities to harness urbanisation for industrialisation require a cross-sectoral and strategic perspective further driving economic and urban and spatial planning.

What this means is that while industrial policies should allow for sector and sub-sector targeting, strategies must be tailored to the specific spatial needs of these targeted sectors. In this way, varying types of cities should be developed to match the needs of the different industries, allowing for spatial targeting to determine where certain industries should be located and specific infrastructure investment directed.

This type of investment has been associated with uncertainties around future returns, land rights, political risk and clarity for developers regarding where growth might occur, particularly in developing countries. However, they can be overcome through mechanisms such as sunk investments. Taken on by a group of investors or governments, sunk investments can prompt and coordinate other potential investors.

The institutional dynamics at play in the governance of urban areas are complex and layered. The political ideologies of local government, and any subsequent strategies of 'returning to the land', play a major role in the importance of urban areas and whether urban challenges are addressed. Layered on top of this is the element of urban primacy. If there is a single large capital city, often three or four times larger than the next largest city in the country, it serves as an important political chess piece in local politics in terms of negotiating power and centrality. Maputo in Mozambique is an example. Urban primacy also strongly influences national issues such as transport, land use and complex governance at the level of the city.

With the increase in consumer demand that cities bring, important new actors in the space include private sector players that have an increasing impact on the landscape of policy, particularly when compared to the influence of civil society pressure groups, scholars or even the development industry. This may be related to growing foreign direct investment (both highly targeted and partial investments) making its way into African countries and changing the African urban landscape.

Urban land management and land use control are governed by two regulatory systems: traditional land use controls mainly intended for subsistence-based settlements, and laws administered by municipalities.

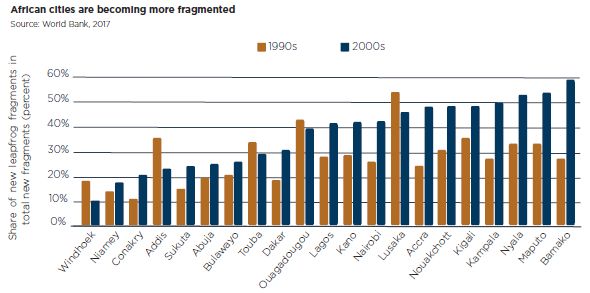

The colonial context for which these laws were designed, to protect a small group of elites, is now applied in a postcolonial Africa, to provide for the majority. It is an ill-fitting template for urban planning, land use regulation and public housing. The result is that African cities are becoming more fragmented, as shown in the graph overleaf.

The mode of urbanisation of African cities is predominantly informal and this is reflected in social and economic reproduction.

Residents depend partially on the state and partly on traditional leaders and faith-based organisations as critical institutional intermediaries. One downside to these overlapping and sometimes competing systems of power is that it is often unclear who is responsible for efforts to improve the lives of urban inhabitants.

Lastly, while localised approaches to urban planning and local technological solutions to urban challenges are important, it is crucial to support them through relevant financing options and empowerment of the appropriate stakeholders.

Local initiatives benefit from the informal network of operators within urban areas who understand the context, are constantly innovating and have existing relationships that enable them to deliver services for themselves. Examples are mobile payment systems such as M-Pesa in Tanzania and Kenya and now taking off in South Africa, and traffic problems being tackled by a team of Congolese engineers in Kinshasa.

Conclusion

A splintered history and a rapid explosion of growth are the trademarks of African urbanism. The lack of institutional oversight needed for the supply of basic services and infrastructure to keep up with this population boom has led to sprawling growth and a deficit in safe housing, water, sanitation, waste management and connected, efficient public transport.

According to the WEF, where they do exist, these basic services cost urban African residents 29% more than what other non-African city residents with similar income levels pay.

In order to harness the transformative power of cities, development of African urban areas must walk the line between sustainable urban development, encouraging economic growth and relieving social equity pressures.

The starting point would be viewing the cumulative crises occurring in African cities as an opportunity. Development should not be solely informed by approaches from the Global North, but by successful local initiatives that ensure urban living is affordable and inclusive of the African urban majority. Such development should take advantage of the opportunities inherent in the dynamism of the informal sector and bridge the infrastructure gap within African cities through accelerated investment in transformative tools for change, such as smarter urban infrastructure and investment in the 4IR.

Second, the structural transformative power of cities is dependent on urbanisation coupled with industrialisation. While key opportunities exist, the overlapping and complex institutional dynamics at play in the governance of cities creates an environment that is daunting in its unpredictability. Policy responses need to be guided by a strategic national-level vision of urbanisation and require a cross-sectoral and strategic perspective further driving economic and urban and spatial planning.

Last, it is critical to address the deeper structural problems associated with African cities when seeking to design and build cities of the future that work for their citizens and are affordable and connected (economically dense). Urban regulations need to be reformed and must be enforced and rewarded, investment and development must be enabled, and policies must tackle land use mismanagement and fragmented development, while encouraging a productive economy.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.