Three recent decisions of the Assistant Commissioner of Trade Marks in New Zealand demonstrate the power of trade mark revocation (aka "non-use") actions in New Zealand, if the registered trade mark has not been used in relation to all of its registered goods or services. This continues on from a number of recent cases which I discussed throughout 2019 and 2020 and highlight the strategic advantages which exist in seeking revocation of a New Zealand trade mark registration.1

Are brochures "use" of a trade mark?

In Nitro AG v Nitro Circus IP Holdings LP [2020] NZIPOTM232, Nitro AG sought to defend use of its NITRO mark in classes 25 and 28 against a revocation/non-use action by Nitro Circus IP Holding LP (Circus). In this case, Circus was smart enough to adopt a series of cascading dates upon which the relevant NITRO marks should be removed, including a date that predated Circus' own application for its own application for its NITRO CIRCUS trade mark. This strategy avoided the concept of "zombie" marks recently considered by New Zealand's highest court.3

This case demonstrates clearly just how clinical and precise the Assistant Commissioner will be when considering evidence in a New Zealand revocation action. That said, the Assistant Commissioner stated expressly that she was conscious of "an overly molecular approach of considering each item of evidence individually: the evidence must be considered as a whole"4, as well as carefully considering the key case of MELTAL MAN5, in which a single advertisement was sufficient to defeat a non-use action.

The Assistant commissioner also considered that "it is not fatal to the owner's case that there is no evidence confirming that NITRO branded clothing was in fact exhibited or sold at the NZSIF trade fares. it is sufficient that the NITRO mark was used as a badge of origin for clothing in catalogues, involving at least one third party, which were clearly aimed at the real commercial exploitation of the trade mark in the New Zealand snow sports market within the relevant time frame"6

In this case the brand owner relied upon trade fair catalogues which circulated in New Zealand at trade fairs within the relevant non-use period. Whilst the brand owner could not provide the exact circulation of those catalogues they did "constitute objective evidence of real commercial exploitation of the NITRO mark in the New Zealand market"7. However in relation to clothing, the catalogues only indicted promotion of ski jackets and ski pants, whilst the brand owners registration covered "clothing including sports clothing". Consequently, the brand owner could maintain its registration in class 25 but only in relation to "jackets and pants for snow sports".

A similar analysis followed in class 28. Much of the evidence which the brand owner relied upon could not be considered as it was either undated, post-dated or unclear. This demonstrates the hard line which New Zealand takes in relation to evidence, unlike its cousins in Australia.

This NITRO case is once again a good demonstration that in New Zealand revocation actions, it is quality not quantity that counts in relation to evidence.

What about "special circumstances" - the Cidirol case?

In INTERAG v Bayer Intellectual Property GmbH [2020 NZIPOTM 218 the brand owner Interag claimed special cirumstances to try and defend its CIDIROL trade mark registration for pharmaceuticals, against Bayer Intellectual Property GmbH's (Bayer) revocation application action.

Interag used the CIDIROL trade mark on a fertility enhancer product for animals which had an oestrogen active ingredient. However, in 2007 New Zealand introduced a ban on oestrogen products for animals which produced food for human consumption. Consequently, Bayer applied for removal of the CIDIROL registration. Interag alleged that the ban created "special circumstances", as Interag literally could not legally sell its specific CIDIROL branded products in New Zealand.

How "special" are "special circumstances" in New Zealand revocation actions?

Its turns out, very special. The term "special circumstances" is not defined in the New Zealand Trade Marks Act, and previous cases considered that the term should be given its ordinary meaning. In this case, the Assistant Commissioner considered that special circumstances "must justify departing from the strong public interest in preventing unused trade marks clogging up the Register and creating no go zones"9

The Assistant Commissioner also dismissed Article 19 of the TRIPs Agreement which allegedly cited import restrictions or other Government requirements as examples which may justify non-use.

Is a Government ban on the branded products "special"?

There is no dispute that the Ban was both out of the ordinary and a one-off product specific event10. Nonetheless, the Assistant Commissioner did not consider it "special" as the ban only prevented the trade mark being used on a specific class 5 product, not all of the goods covered by the registration - i.e. Interag was free to use the mark on other goods. Furthermore, Interag's argument that use of the same or similar mark on other class 5 products would cause confusion was dismissed, largely due to weaknesses in the evidence itself and as the target market (veterinarians) are both highly trained and likely to be aware of the ban on the CIDIROL branded product. The Assistant Commissioner held that "Interag gave up on the CIDIROL trade mark when the ban came into force" and Interag's assertion of a confusion risk was considered to have been raised a "a convenient basis on which to mount a defence to a competitors application for removal of an unused mark"11. So, Interag lost its CIDIROL registration

The case stands as a strong warning that just because a brand owner cannot not sell its specific branded product in New Zealand, this does not necessarily create "special circumstances" sufficient to defeat a revocation action.

IPONZ restricts narrowly again and provides a good overview of its position

In the Office of the Retirement Commissioner v Cash Converters Pty Ltd [2020] NZIPOTM 27 (23 December 2020)"12. The Assistant Commissioner restricted the Office of the Retirement Commissioner's (ORC) registration of trade mark SORTED to the very specific services for which the mark has been used, in response to Cash Converters' revocation action. This decision demonstrates clearly why New Zealand revocation actions can be a helpful addition to any brand owner's global toolkit, especially if it needs to "raise the ante" in negotiation of an international trade mark dispute.

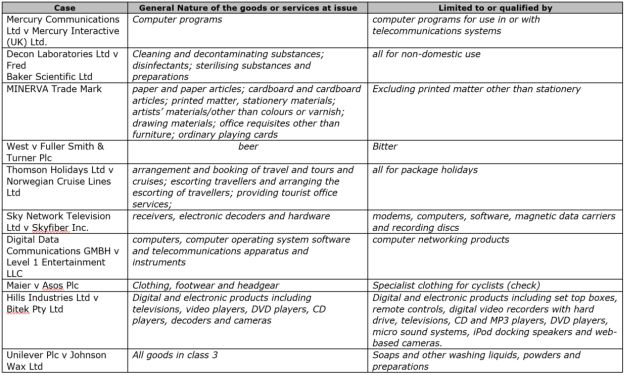

After the parties quibbled as to whether or not Cash Converters was a "person aggrieved" (another trap for Australian attorneys who only dabble in New Zealand) the Assistant Commissioner provided an excellent and very helpful summary of how the coverage of NZ trade mark registrations have been narrowed in assessing numerous revocation actions and which he considered "instructive", namely:

The Assistant Commissioner then commences upon a very careful and clinical analysis once again, to identify a fair description of the services that are provided under the sorted trade mark, namely [13]:To this table we can add the recent case I discussed last year in which Unilever could not even retain coverage for "dried, frozen and canned peas" when it had only used the mark for "dried peas", with IPONZ insisting that the registration is restricted accordingly just to "dried peas" 14

- Class 36 specification (Regn no 637400) Providing information services and general advice relating to finance, investment and financial planning for and during retirement; providing financial information and general advice relating to retirement by means of telecommunication and electronic networks including online, via a global or other communications network, the worldwide web, an intranet or the Internet

- Class 36 specification (Regn 976028) Providing information and general advice, including online, about insurance, financial and monetary affairs and real estate affairs related to retirement and personal finance; provision of financial calculation services relating to retirement and personal financial planning including budgeting, personal debt, home buying, mortgages, superannuation, investment and savings, including by way of online calculators; providing information services and general advice relating to finance, investment and financial planning for and during retirement; providing financial information and general advice relating to retirement by means of telecommunication and electronic networks including online, via a global or other communications network, the world-wide web, an intranet or the Internet.

- Class 41 specification (Regn 976028) Education services related to retirement and personal financial matters including financial planning and budgeting, debt, home buying, mortgages, superannuation, investment and savings; provision and dissemination of educational material and information related to retirement and personal financial matters, including by way online communication, websites, web blogs, social media, forums, publications (including texts, guides and brochures), news articles, training, courses, seminars and meetings.

What's missing? "Advisory and consultancy services"

Many service providers will also register their brand for "advisory and consultancy services". The Assistant Commissioner did not consider that retention of either term that was fair or appropriate in this case an ordered that they be removed, along with umbrella terms such as "financial services". In so doing, the Assistant Commissioner provides a warning to other service providers who have registered their marks in New Zealand, about possible "pruning" which may occur if their own trad mark registration is the target for a revocation action.

Where did these cases take us? Throwing New Zealand revocation actions into your toolkit

Independently each of these cases may seem somewhat unremarkable. However along with other New Zealand revocation cases I have discussed over the last couple of years, these cases reinforce why New Zealand non-use revocation actions should be included in any brand owner or IP lawyers "toolkit", particularly if dealing with the dispute either in Australia or internationally. When we compare these actions to their Australian equivalent, there are some key take away points:

- There is no discretion in New Zealand revocation actions;

- The evidence required in New Zealand non-use actions must be of high quality and will be scrutinised heavily;

- Brand owners on the receiving end of a New Zealand non-use revocation action will need to be prepared for their coverage to be restricted narrowly and precisely to the specific goods or services which the mark has been used; and

- Such restriction is likely to be much more extensive than that which may occur in Australia

Footnotes

1. https://dcc.com/news-and-insights/new-zealands-highest-court-find-that-zombies-do-exist-in-new-zealand-after-all; https://dcc.com/news-and-insights/no-surprises-but-a-new-zealand-removal-case-provides-a-good-warning-about-the-scope-of-removal-actions; https://dcc.com/news-and-insights/new-zealand-court-rules-on-the-effect-of-non-use-actions-lodged-against-cited-trademarks; https://dcc.com/news-and-insights/lascoste-loses-a-crocodile-in-new-zealand-revocation-action-removal-backdat

2.http://www.nzlii.org/cgi-bin/download.cgi/cgi-bin/download.cgi/download/nz/cases/NZIPOTM/2020/23.pdf

3.https://dcc.com/news-and-insights/new-zealands-highest-court-find-that-zombies-do-exist-in-new-zealand-after-all

4. para 73, citing Pan World Brands Ltd v Tripp Ltd [2008] RPC 2

5. Metalman New Zealand Limited v Scrapman BOP Limited [2014] NZHC 2028

6. para 80

7. para 74

8.http://www.nzlii.org/cgi-bin/download.cgi/cgi-bin/download.cgi/download/nz/cases/NZIPOTM/2020/21.pdf

9. para 76

10. para 97, 98

11. para 140

12.http://www.nzlii.org/cgi-bin/download.cgi/cgi-bin/download.cgi/download/nz/cases/NZIPOTM/2020/27.pdf

13. https://dcc.com/news-and-insights/no-surprises-but-a-new-zealand-removal-case-provides-a-good-warning-about-the-scope-of-removal-actions

14. para 119

Originally published 8 February 2021

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.