In several previous issues of WCR we have described how hybrid legal entities could be used to reduce the worldwide corporate income tax burden of a multinational group, as a matter of legal principle. In this issue we will describe, at the request of several readers who have commented positively to my earlier articles, a detailed example of what is possible with hybrid entity tax planning in day to day tax practice.

The use of two hybrid Dutch entities for a chemicals production company that wants to enter Europe in various countries simultaneously

Phase one: avoiding exit tax upon IP transfers to the new jurisdictions

This case involved a company in a high tax jurisdiction that was considering start-of-production locations for their chemical products in various European countries. The company is profitable in its home country and seeks to avoid additional tax there on income related to the transfer of the intangibles it uses at home to the new European production locations; in addition it is interested in keeping foreign profits tax low. Can the Netherlands play a role in the tax planning required?

The first issue to address is clearly to avoid taxation on the transfer of product technology and production technology plus a marketing intangible (the "client list") from the parent company of the group to the new production locations. An immediate and taxable capital gain on such transfer can be avoided by transferring the intangibles mentioned to newly set up foreign subsidiaries against an "arm's length" royalty payment but this would still risk additional taxable income, as of day one, in the home country of the parent whilst the new subsidiaries will generate start-up losses so the tax deductibility of their royalty payments do not reduce foreign tax for a number of years.

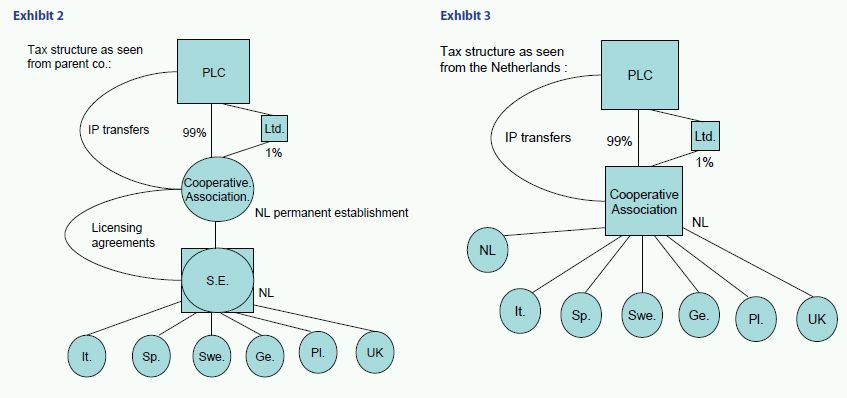

An exit charge on the IP in the group's home country could perhaps be prevented by using a hybrid legal entity to transfer the IP to: this entity should form a so-called "permanent establishment" of the parent company abroad, which would avoid the exit charge because no transfer to a separate legal entity will take place under the home country's tax laws. If this could be coupled to a situation whereby the foreign operations are seen, under the tax rules of the country at the receiving end of the IP transfer, as a "tax entity" one might be able to get a so-called "step up in basis" for the IP which it receives from its foreign parent. Can such a hybrid entity ("permanent establishment" [non-resident tax payer] as seen from the parent in the group, local tax payer as if it was a separate entity [resident tax payer] as seen from the subsidiary itself ) be structured in a country which will also allow other multi-country tax benefits? This question was asked by the foreign parent company to several tax advisers in European countries, including to me.

My answer for the Netherlands, but form a multi-country investment purpose, was as follows:

A Dutch "Cooperative Association"' could well be the hybrid instrument to look for. It has all the hallmarks of a partnership under the tax laws of many foreign jurisdictions, which gives rise to a tax treatment in the home country as a foreign permanent establishment, but nonetheless, from a Dutch corporate income tax viewpoint it is an entity subject to tax itself: the "members" or "partners" will not become taxable in the Netherlands. The Coop will be treated like a Dutch limited liability company (see WCR December 20091).

If a Dutch tax entity acquires IP for book value, this will have to be disregarded for Dutch corporate income tax purposes: assuming that the fair market value of the IP transferred (product technology and production technology plus one or more marketing intangibles) exceeds the book value for which the transfer will unavoidably take place, the Coop can take this difference into account in a tax favourable manner in Holland:

The Coop may capitalize the entire fair market value (to be established on the basis of a transfer pricing report) in its tax balance sheet and depreciate it over the useful economic lifetimes (each IP element may have a different life cycle in this respect). Dutch case law holds that a transfer of a business asset between related parties for a "wrong" price can analytically be seen as 1) a transfer against the right price, in combination with 2) a gift by the parent to the subsidiary of the excess;

An "advance tax ruling" is normally available in Holland to determine, at the outset of the new structure, what amounts the Coop can show as annual tax depreciation in its corporate income tax filings.

Once the above has been completed successfully, the group may, depending on its home country system to avoid double taxation:

1) Have avoided an immediate increase in its home country taxation because of the transfer of the intangibles; 2) Maybe also have avoided a future, annual, increase in its home country taxation because of the IP transfers; 3) Whilst at the same time safeguarding a meaningful tax deduction in the country to which the IP was transferred, if needed via tax loss carry forwards in case the Coop would run into start-up losses as is not unusual when starting up new business sin a new jurisdiction.

My advice, obviously, did not cover the home country tax system of the parent in the group. The obvious tax questions, to be answered by home country tax counsel or the in-house tax department, will have to focus on the ways in which a transfer of IP to a foreign partnership such as a Dutch Coop will affect taxable profit, not only upon the transfer but also in future years. How does the home country tax system deal with foreign "branch" profits? Will they be exempt? Or will there be a credit for the foreign tax incurred? This is beyond the scope of this article, however.

Phase two: expanding the tax effective IP usage to other European countries

The client clearly wanted to set up businesses in several European jurisdictions in a tax effective manner simultaneously, so the tax planning continued. Could we use the IP, transferred to a Dutch hybrid Coop, in other European countries as well and would some further creative tax structuring be possible with the Dutch Coop as the starting point?

In an earlier article (WCR March 20102.) we have discussed the possibility to make a Dutch BV disappear for tax purposes in Holland, whilst it did not disappear in other European countries where it did business. A simple but real hybrid entity therefore. The foreign European operations would then either need to take the form of genuine branch offices (permanent establishments) which is not a rocket science assignment, or one could work with foreign hybrid LLP's (the subject of another earlier WCR article I wrote, see WCR June 20103.). Such LLP's would be tax transparent in the countries of operations but Holland would treat them as foreign subsidiaries under the somewhat peculiar Dutch "foreign entity classification rules" in its Corporate Income Tax Act, which distinguishes between so-called Open Limited Partnership and Closed Limited Partnerships for Dutch purposes. But my country uses these same rules to classify foreign "joint venture" models, to distinguish them between foreign "quasi-subsidiaries" and foreign "quasi-branches", regardless of how the country of operations classifies these LLP's itself.

A third and even very intriguing possibility, to arrive at a Dutch tax payer with foreign branch operations, is to create a pan-European legal entity structure in the form of an SE (Societas Europaea), a legal entity proudly introduced by the European Commission in 2004 whereby one only needs one limited liability entity in the EU, which is then governed by the same civil law or common law rules in all EU countries. A big disadvantage of the SE concept has been that if an existing business, already consisting of different legal entities in various European countries (such as an SarL in France, a GmbH in Germany, an A/B in Sweden etc.) would be converted into an SE, this would imply the liquidation, for tax purposes, of all legal entities in all other countries than the country where the SE ends up, so exit taxes would become due so the SE has always been denominated as "the still-born EU child of 2004". But if one sets up new business, rather than converting an ongoing business, this disadvantage does not apply. In fact the disadvantage turns into an advantage: setting up an SE in one EU country, which subsequently does business in its own name in several other EU countries, will automatically and in very straight forward fashion lead to the desired tax result: a hybrid entity in one EU country with foreign branch operations in all other EU countries.

Note that setting up an SE entity is by no means an easy procedure for a group which does not already possess European legal entities, due to severe restrictions in the EU statute for SE's, but this aspect, however important, is outside the scope of today's article.

Turning back to the article I wrote on hybrid BV's in WCR March 20102, and emphasizing that "BV" can always be replaced by "SE" because the tax planning consequences will be the same, we will now structure the final piece of the tax planning exercise: the Coop on top of the Dutch structure possesses tax depreciable IP because of the step-up in basis discussed earlier. If it licenses this IP to its subsidiary-SE, which operates the branch offices elsewhere in Europe, the branches, under article 7 of the OECD Model Treaty, which has been incorporated – on this particular subject – in almost every real tax treaty, will become entitled to a tax deduction for their pro rata share of the royalty payments which the Dutch SE has to make to the Dutch Coop. Here the transfer pricing report needed to determine the stepup in Phase I will come in handy again, as it will show the "arm's length" value of the IP rights.

Let's say the Dutch SE also sets up business in Italy, Spain, Sweden, Germany, Poland and the UK. These operations will produce chemical products with the help of (perhaps even patented) product technology and production technology. In addition they will obtain the client list for their country and other marketing intangibles, previously in the hands of the parent company of the group before it decided to start operations in Europe.

Provided the royalty payments between SE and Coop are "at arm's length" and also provided that the division key which the SE uses to spread the royalty payments over its various branches is in order (again: a TP issue), the Italian, German, UK etc. operations will be able to get a tax deduction for these payments, even if the payments do not come from them but from the Dutch head–office (on their behalf).

How big a deal is this, then? We have royalty expense deduction in the foreign branches of the SE (pro rata), in the SE itself (for the Dutch production site) but this leads to royalty income in the Dutch Cooperative. This is a Dutch tax payer, subject to the standard 25% Dutch corporate income tax rate on all business income including the exploitation of intangibles, so why would anyone want to put income into it?

Here's where the hybrid character of the lower Dutch entity in the structure comes in: Dutch Coops qualify for Dutch tax consolidation, as parent companies. SE's qualify for Dutch tax consolidation either as parent companies or as subsidiaries (although this is not common knowledge at all in Holland, but we have written confirmation from the Dutch Ministry of Finance on this).

So if I now take you back to my earlier WCR article on hybrid Dutch BV's (WCR March 20102.), and now knowing that Dutch SE's are treated the same way, tax wise, as Dutch BV's and now also knowing that the SE can be part of what is known in Holland as "fiscal unity", you may draw the proper conclusions together with me:

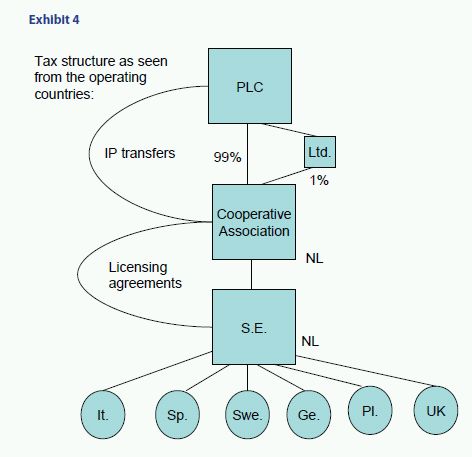

1) For Dutch corporate income tax purposes the SE does not exist!

2) As a direct consequence of this fiction, the licensing contract between the Coop and the SE does not exist either! One cannot license intangibles to oneself (in the Dutch tax consolidation concept, the SE has been absorbed by the Coop, it has in fact become a Dutch permanent establishment of the Coop);

3) So from a Dutch corporate income tax viewpoint, there are no royalty payments from the SE to the Coop. And invisible income is non-taxable.

We therefore end up with a situation where, regardless of the fact that in Germany, Sweden, Poland, the UK etc. a tax deduction may be claimed and must be granted by the tax authorities on the basis of the tax treaty with Holland for a pro rata share of the royalty payments between the Dutch SE and the Dutch Coop, there is no income pick-up in Holland.

This "phase 2" set-up has been the subject of Supreme Tax Court litigation between 1987 and 2003 (that is how long it might take for a case to be finally dealt with in my country, but litigation time in Holland is no exception compared to other jurisdictions), with an ultimate total victory for the tax payer concerned. The Dutch Supreme Tax Court not only decided in 2003 that:

(1) Set-ups like the one shown do indeed have the effect of disappearing income but also that:

(2) This tax planning cannot be disregarded as abuse of law either, because in the Supreme Court's view there is no Dutch tax at stake: if the Coop would not set up an SE to license its IP to, and form "fiscal unity" with it, but would set up its own foreign branch offices, where its IP would be used, Dutch taxable income would equally not show royalty income: all income would be earned by the branches and all branches other than the Dutch one would be exempt from Dutch corporate income tax, under the standard Dutch foreign branch income exemption rules.

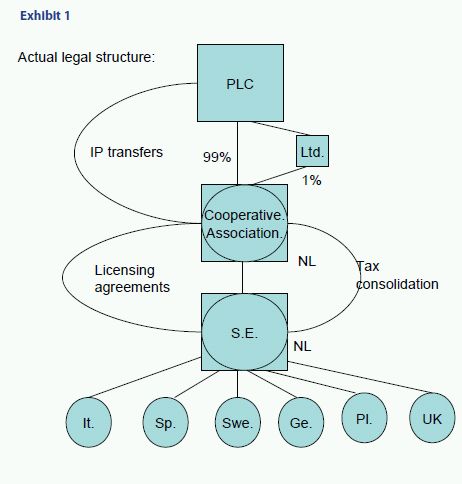

Below I have depicted the structure as seen under the tax rules of the countries involved, which clearly show two hybrid entities: the Dutch Coop and the Dutch SE. You will note that such structures are not necessarily restricted to the Dutch operations of multinational enterprise alone but can on the contrary be made to work, not only for many foreign parent company jurisdictions, but also for many operational jurisdictions.

Footnotes

1. The use of hybrid legal entities in group structures of multinational enterprises, WCR Volume 3, Issue 4, December 2009 http://worldcommercereview.com/publications/article_pdf/202

2. The use of hybrid legal entities in group structures of multinational enterprises, Part II, WCR Volume 4, Issue 1, March 2010 http://worldcommercereview.com/publications/article_pdf/243

3. The use of hybrid legal entities in group structures of multinational enterprises, Part III, WCR Volume 4, Issue 2, June 2010 http://worldcommercereview.com/publications/article_pdf/273

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.