The following appeared originally in Wolters Kluwer's Tax Topics.

Special thanks to Caroline Elias, associate at Minden Gross LLP, for her assistance in reviewing earlier versions of the Series and to Joan Jung, tax partner at Minden Gross LLP, from whose presentations and papers I've borrowed liberally. All errors and omissions are my own.

Part 1 of this Series2 reviewed what is meant by control for purposes of the Income Tax Act (Canada) (the "Act") and also reviewed some of the key tax implications of control under the Act. In this second instalment of the Series, we'll delve into some additional tax rules regarding the application of control in the Act and we'll examine tools to determine de jure control ("DJC"), with an emphasis on the impact that a unanimous shareholders agreement ("USA")can have on DJC.

Statutory Extension of DJC

Paragraph 251(5)(b) statutorily extends the concept of DJC for purposes of determining Canadian-controlled private corporation ("CCPC") status, as well as whether persons and corporations are related and also non-arm's length. Often the application of this provision can lead to unintended negative tax consequences.

Although the rules in paragraph 251(5)(b) are incredibly broad, the provision will not trigger the loss restriction event rules in subsection 251.2(2) of the Act, as those provisions require an actual acquisition of the securities giving rise to an acquisition of DJC.

Paragraph 251(5)(b) will be discussed in more detail in the third instalment of the Series.

DJC and DFC—Groups of Persons

The DJC and de facto control ("DFC") concepts both may involve groups of persons. However, the meaning and nature of groups of persons can differ widely depending on how the group concept is used in the Act.

The general rule is that to have a group there must be "a sufficient common connection" among the group membersso that they would be able to exercise control. This might occur where there are voting agreements in place, partiesact in concert, or might be acting at non-arm's length with one another.3

In some provisions of the Act, only related or affiliated groups of persons are relevant. In other provisions, the groupmay not need to be related or affiliated.

However, pursuant to paragraph 256(1.2)(a), it appears that no common connection is required when determining whether there is a group of persons for purposes of the association rules.4

Ignoring paragraph 256(1.2)(a), a typical representation of the views of the Canada Revenue Agency ("CRA") on parties forming a group is exemplified by the CRA's position in Income Tax Technical News no. 7:

Although the requirement to act in concert is relevant in determining whether a group of persons controls any corporation, it is also our view that certain presumptions are appropriate in the case of closely-held corporations. For example, in a closely-held situation, the fact that shareholders jointly adopt mutually advantageous measures is an important indicator of acting in concert.5

Given such a broad statement, is there any way to know how shareholders agreements, including USAs, might impact the determination of whether taxpayers constitute a group of persons?

The answer appears to be uncertain. Generally, one would expect that the mere entering into of such agreements should not result in a group coming into existence. However, it is necessary to look at the terms, context. and history surrounding the agreement before coming to any definitive conclusions.

Tools To Determine DJC

Because control, whether DJC or DFC, is so critical to so many aspects of the taxation of private corporations in theAct, 6 anything that can impact on DJC or DFC requires careful consideration.

For DJC purposes, DJC is not determined by simply adding up voting rights. For example, to determine DJC one must review the relevant corporate statute and so-called "constating documents", which typically include the corporation's articles, including share rights, by-laws, and share register. Following this review, one must also consider whether certain other key documents impact the ability of a shareholder or group of shareholders to elect the board of directors.7

In some circumstances, agreements that are incorporated by reference into a corporation's articles, such as anamalgamation agreement, will be relevant to the analysis. 8 When trusts are shareholders of a corporation, the fiduciary nature of the obligations of the trustees as set out in the trust agreement can cause the trust agreement to be a document that can impact DJC.9

Another key document that can impact DJC is a USA. 10 A USA is a special type of shareholders agreement that meets the requirements of the particular governing statute of the particular Canadian jurisdiction.11

As the focus of this Series is on how shareholders agreements can impact control for purposes of the Act, the next portion of this article will examine the impact of shareholders agreements that qualify as USAs on DJC.

USAs and DJC

The mere existence of a USA does not change DJC or cause a majority shareholder or majority group of shareholders to lose DJC. Nevertheless, where a USA is in place, it is necessary to determine whether the USA can impact the ability of the majority shareholder or majority group of shareholders to exercise effective control over the affairs and fortunes of the corporation in a way analogous to the power to elect a majority of the board of directors that could impact DJC.

Three important cases, Duha, Alteco Inc. v. The Queen ("Alteco"), 12 and The Queen v. Price Waterhouse Coopers Inc. acting in the capacity of Trustee in Bankruptcy of Bio artificial Gel Technologies (Bagtech) Inc. (" Bagtech"), 13 each of which involve a review of the impact of USAs on DJC, are discussed below to illustrate how, if at all, USAs can impact DJC.

Duha

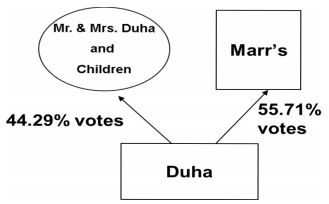

The share structure in Duha is graphically reproduced below.

In Duha, DJC was an issue because the corporation, Duha Printers (Western) Ltd. ("Duha Ltd."), had acquired ownershipof Outdoor Leisureland of Manitoba Ltd. ("Outdoor"), which had accrued significant non-capital losses, from Marr'sLeisure Holdings Inc ("Marr's"), the 56% controlling shareholder of Duha Ltd. If the acquisition of Outdoor had caused achange in DJC of Outdoor, then the ability of Duha Ltd. to use the non-capital losses would have been severely restricted.

In the absence of a USA, since the 56% shareholder was related to Duha Ltd., no change of DJC should have arisen. However, the SCC found that a determination of DJC required an examination of how, if at all, the USA impacted DJC.

The only substantive restriction on the rights of the majority shareholder in the USA governing Duha Ltd. was that the board of directors could only be chosen from a limited group of individuals—but this did not stop the majority from voting its shares as it pleased. 14 As a result, the existence of the USA in Duha was held not to impact the majority shareholder's effective control (DJC) of the corporation.

Alteco and Bagtech are illustrations of cases where a USA was held to affect the majority shareholder's effective control and impacted DJC.

Alteco

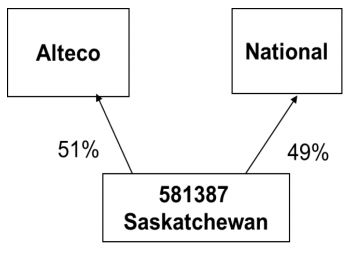

The share structure in Alteco is graphically reproduced below.

In Alteco, Alteco Inc., the majority 51% shareholder, had certain amounts owing to it (the "Receivables") by 581387Saskatchewan Ltd. ("387") and wanted to trigger allowable business investment losses ("ABILs") in respect of the Receivables.

If Alteco Inc. had DJC over 387, then the two corporations would be related and therefore not dealing at arm's length with one another, which would have resulted in the ABILs being denied under subparagraph 39(1)(c)(iv). However, based on the terms of the USA, which only entitled Alteco Inc. to elect 2 of the 5 members of the board of directors of 387, Alteco Inc. was found not to have DJC over 387 so that the claim for ABILs was permitted.

Bagtech

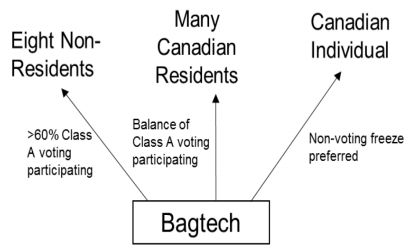

The share structure in Bagtech is graphically reproduced below.

In Bagtech, the issue was whether or not Bioartificial Gel Technologies (Bagtech) Inc. ("Bagtech Inc.") was a CCPC.

As was discussed in part 1 of this Series, paragraph (b) of the definition of CCPC in subsection 125(7) has a specific rule that requires one to imagine a hypothetical situation that would aggregate all of the shareholdings by non-resident and certain public shareholders in a single hypothetical shareholder, and to then ask if the hypothetical share holder would have DJC over the corporation. Because the eight non-resident shareholders of Bagtech Inc. had more than 60%of the votes, if one had applied the paragraph (b) test with reference only to the shareholders register, then the non-residents would have been considered to have had DJC over Bagtech Inc. and Bagtech Inc. would not have qualified as a CCPC.

However, since the shareholders of Bagtech Inc. had entered into a USA, a simple analysis of the shareholders registerwas not sufficient to dispose of the DJC analysis and it was necessary to also consider what impact, if any, the USAmight have on DJC. Upon examination of the USA, the FCA determined that the hypothetical shareholder could no thave elected more than 50% of the board of directors. Consequently, notwithstanding the non-resident shareholder shaving over 60% of the votes, they did not have DJC over Bagtech Inc. for purposes of paragraph (b) of the CCPC definition and Bagtech Inc. continued to be a CCPC.

CRA's Response to Bagtech

Following Bag tech, the CRA released two technical interpretations15 that appear to have somewhat grudgingly accepted the Bag tech decision. In particular, the CRA indicated that it would adopt Bagtech "where appropriate" in determining which shareholder or group of shareholders has effective control. On the other hand, the CRA also noted that there could be other provisions in a USA which affect "effective control" 16 or control "in the long run". 17 In addition, theCRA also indicated that it would review specific cases to determine if there could be an avoidance transaction, inwhich case it might assess under the general anti-avoidance rule ("GAAR") in section 245.Planning Points—DJC and the Decided Cases These three cases illustrate how USAs can impact DJC. It is also worth keeping these cases in mind because they may assist in planning to achieve desired tax results under the Act — either by planning to have or not to have DJC apply in any particular situation.

Interpretation, Business and Employment Division, March 19, 2019, Document No. 2018-0758641E5

Footnotes

1 Michael Goldberg, tax partner, Minden Gross LLP, MERITAS law firms worldwide, and founder of "Tax Talk with Michael Goldberg", a quarterly conference call about current, relevant, and real life tax situations for professional advisors who serve high net worth clients.

2 Unless otherwise noted, defined terms in this article have the meaning designated in the first instalment of the Series.

3 Silicon Graphics Ltd. v. The Queen, 2002 DTC 7112 (FCA) at para 36.

4 For example, see: Interpretation Bulletin IT-302R3 (28 February 1994). On the other hand, see commentary of Ron Dueck and Stephanie Daniels, "Update and Review of the Related, Affiliated, and Associated Rules: Overlaps, Differences, and Their Significance," in 2014British Columbia Tax Conference (Toronto: Canadian Tax Foundation, 2014), 10:32-33, where the authors suggest that the CRA's views may be overly broad.

5 Income Tax Technical News no. 7, February 21, 1996.

6 For a summary of key impacts see the chart at the end of Part 1 of this Series.

7 Duha Printers (Western) Ltd. v. The Queen, 98 DTC 6334 (SCC).

8 Avotus Corp v. The Queen, 2007 DTC 215 (TCC).

9 Supra note 7.

10 Supra note 7.

11 For example, see s. 146 of the Canada Business Corporations Act, RSC 1985 c C-44. Typically a USA, unlike an ordinary share holders agreement, must be in writing and signed by all of the shareholders (a declaration by the sole shareholder of a corporation can qualify as a USA). Most jurisdictions require that the powers of the directors must be restricted pursuant to the terms of the USA (Alberta's corporate legislation does not contain this requirement).

12 [1993] 2 CTC 2087.

13 2013 DTC 5155 (FCA).

14 The USA contained general share transfer restrictions (i.e., with shareholder approval) but this was not considered to be a problematic provision.

15 CRA document no. 2014-0523301C6 (6 May 2014), and CRA document no. 2016-0662381E5 (24 March, 2017).

16 Supra note 7, para 36.

17 Donald Applicators Ltd et. al. v. M.N.R., 69 DTC 5122 (Ex. Ct.).

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.