The Ontario government disagreed with the Federal government's decision to impose a fuel charge to combat climate change. To show its displeasure, the Province passed legislation that required gasoline retailers to post stickers on gas pumps that read "The Federal carbon tax will cost you." Failure to post the stickers would trigger substantial penalties on gasoline retailers.

The Canadian Civil Liberties Association (CCLA) brought an application to strike-down the legislation, styled the Federal Carbon Tax Transparency Act, 2019. The CCLA argued that the legislation amounted to compelled speech contrary to freedom of speech enshrined in section 2(b) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (Charter). The Province argued that the stickers contained information relevant to the consuming public and that it did not require gasoline retailers to agree or disagree with the content or otherwise restrict them from posting contrary views.

In a recent ruling, the Hon. Justice Edward Morgan of the Ontario Superior Court of Justice struck-down the legislation on the grounds that it violated the Charter.

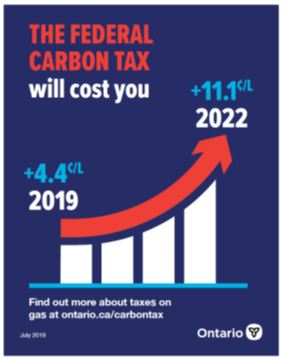

To frame the debate, a preliminary issue was whether the federal legislation was a carbon tax versus a fuel charge. The federal government imposed a fuel charge in certain provinces starting at 4.4 cents/litre of gasoline in 2019 rising to 11.1 cents/litre in 2022. In 2018, the Province challenged the constitutionality of the federal legislation. It lost. The Court of Appeal for Ontario held that the federal charge was within the jurisdiction of the federal government. Carbon emissions were of "national importance" such that the federal government could legislate in accordance with the Peace, Order, and Good Government clause of s. 91 of the Constitution Act (a clause that has come to be seen as the Canadian counterpart to the American "life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness" and the French "liberty, equality, fraternity").

Importantly, the Court of Appeal held that the fuel charge was not a carbon tax. It wasn't a revenue-raising measure; rather, it was a regulatory charge as part of a larger regulatory scheme to combat climate change. That ruling will be argued before the Supreme Court of Canada shortly. Until then, it was the law of Ontario.

The timing of the imposition of the requirement to post the stickers was also important to the motion judge. The evidence from the CCLA demonstrated that the stickers were required to be placed in the run-up to the federal election of 2018. The Premier of Ontario and cabinet ministers made public pronouncements to the effect that the fuel charge was a tax imposed by the federal Liberal government that Ontario voters deserved to know about. The motion judge held that the evidence demonstrated that the provincial legislation should be understood as forming part of the Province's engagement with federal partisan politics.

The motion judge then considered the concept of freedom of speech under the Charter. Section 2(b) guaranteed both the right to express views and the right not to express views citing Supreme Court jurisprudence as follows: Silence is in itself a form of expression which in some circumstances can express something more clearly than words could do."

Justice Morgan then turned to the factors laid-down by the Court of Appeal for Ontario in McAteer v. Canada (Attorney General) in relation to government-compelled speech:

The first question is whether the activity in which the CCLA is being forced to engage is expression. The second question is whether the purpose of the law is aimed at controlling expression. If it is, a finding of a violation of s. 2(b) is automatic. If the purpose of the law is not to control expression, then in order to establish an infringement of a person's Charter right, the claimant must show that the law has an adverse effect on expression. In addition, the claimant must demonstrate that the meaning he or she wishes to convey relates to the purposes underlying the guarantee of free expression, such that the law warrants constitutional disapprobation.

The first question was easily answered: the sticker was a form expression. The motion judge then turned to answering the question of whether the legislation controlled the expression that a gasoline retailer might otherwise express. He noted that the legislation did not prevent a gasoline retailer from designing a sticker that conveyed whatever message it wanted, even to correct perceived inaccuracies in the Province's sticker. There was thus, no controlling of expression and no automatic violation of section 2(b) of the Charter.

The real issue dealt with the third McAteer question: whether the legislation had an adverse effect on expression and whether it was worthy of "constitutional disapprobation." The motion judge found that the messages on the sticker were tantamount to political missives rather than the consumer messages the Province claimed them to be. For example, the information in the sticker was incomplete in such a significant way that it did not convey the true state of facts. The label "Federal Carbon Tax" that appears in bold, red font at the top of the Sticker was a misnomer given the Court of Appeal's decision that it was a fuel charge and not a tax. The motion judge found that in persisting to call it a "carbon tax" would have been perfectly acceptable in political advertising or in a politician's speech, but that it was an intentional use of "spin" that revealed the advocacy rather than informational thrust of the message. He also found that the sticker omitted to mention that a rebate of the fuel charge that was part of the two-part federal strategy. All told, the Province was not so much explaining a policy, but making a partisan argument that the federal government was gouging taxpayers. All perfectly normal in a political campaign, he held.

Justice Morgan found that the by using the law for partisan ends, the Province had enacted a measure that ran counter to, rather than in furtherance of, the purposes underlying freedom of expression and that warranted constitution disapprobation.

The legislation could not be justified under section 1 of the Charter (see Oakes test). The motion judge referenced the fact that the Supreme Court had made it clear that the use of legislative/executive power for partisan purposes amounted to an unjustified attempt to [legislate/regulate] to benefit the governing party. Evidence of the partisan genesis of the stickers came from a speech by the Ontario Energy Minister in the Legislature that "we're going to stick it to the Liberals and remind the people of Ontario how much this job-killing, regressive carbon tax costs." That was perfectly acceptable in an election campaign, the motion judge held. But the Province could not legislate a requirement that private retailers post the sticker designed to accomplish that task.

Sections of the legislation were held to be of no force or effect. The motion judge ordered that gasoline retailers were at liberty to keep the stickers on their fuel pumps or to remove them, as they saw fit.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.