Overview

There is no question that the Australian economy is in a state of flux. These are challenging conditions for policymakers due to the conflicting signals that currently prevail. Never was this more evident than early last month (June 5) when the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) decided to cut the benchmark interest rate again by 0.25% to "be a little more supportive of domestic activity". The very next day, the March quarter economic growth figure came in at 1.3% (4.3% over the year), which was significantly higher than the RBA and markets were expecting.

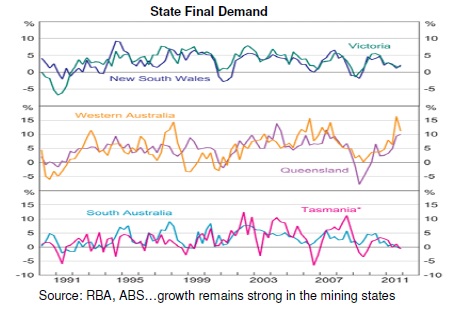

While it is true that the GDP number is backward looking - and indeed a lot has happened since the end of March - it is equally true that our view of the economy is impacted by our perceptions. NSW has a significant financial services employment base and so it is no real surprise that sentiment is rather downbeat, reflecting the poor state of financial markets and the corresponding downsizing that has been evident across the banking, legal, accounting and funds management industries. In contrast, Western Australia, the Northern Territory and to a lesser extent, Queensland continue to benefit from the vast number of mining and infrastructure related projects underway in those states. This is reflected in the state by state GDP data, with WA and NT experiencing growth of 7.8% and 7.2%, while NSW recorded a fall of 0.3%. This contrast is even more evident when business investment is compared. WA grew by 23% over the quarter while NSW fell by 7.1%. The contrast between the mining states and non-mining states could not be more stark.

Of course, this presents particularly difficult challenges for policymakers that must balance strongly divergent interests as follows:

- Monetary Policy The RBA has been faced with balancing the interests of the non-mining states who want lower rates to stimulate the rather lacklustre growth with the risks of lower rates potentially stimulating too much growth in the mining states, which could ignite inflation.

- Fiscal Policy

-

Similarly, on the fiscal front, the Government has had to deal with the other challenges presented by the mining boom. The boom has been a windfall for the miners, shareholders, the considerable number of companies that service the industry, and consumers (by way of cheaper imports). Of course, as the Australian dollar soared a number of industries have struggled. Import competing manufacturing industries and tourism operators have felt the brunt of the impact, as have those who have had to compete with the high cost of labour in the mining regions.

In trying to balance these interests, the Government proposed the mining tax. The initial intent of the mining tax was to, a) increase tax revenue for wealth redistribution purposes (sharing the spoils of the boom across the country); and b) dilute the impact of the mining boom on the non-mining regions by reducing the incentive for mining companies to overinvest.

It was envisaged that by only taxing 'excess' profits, the industry would remain moderately profitable and continue to attract investment but not too attractive so that the non-mining states would suffer . History shows that intense lobbying by vested interests led to a significantly diluted tax regime that has had little effect in achieving the intended outcomes.

While the tax may prove to be a failure, market forces will eventually rectify the mining boom imbalance anyway, but it will take some time. Falling commodity prices and rising labour costs are already causing mining companies to reassess their future investment plans. If this trend continues then it is likely that the Australian dollar will fall and labour cost relativities will ease.

Aside from the mining boom, the other major structural event that continues to have a significant impact on the economy and policy is the house price boom that started in circa 1996 (that has led to high levels of household debt and has only began to show signs of slowly deflating in recent times). The knock on effects have been significant as follows:

- Housing starts remain in the doldrums, but they remain in the doldrums for a reason. Unsustainable housing bubbles are formed when price growth outstrips income growth, which is exactly what occurred over the period from circa 1996 -2004. Fortunately growth since then has been more subdued but until prices fall much further or incomes gradually adjust, investment in this sector will remain well below trend. So while the industry lobbies the government to stimulate demand by extending grants, they should be lobbying the government to do the exact opposite because only by changing the laws of supply and demand will the industry move back to a sustainable growth trajectory. By this we mean that either prices have to fall or the government dramatically increases supply (releases more land/build low cost housing) which has the effect of reducing overall prices.

- Over inflated house prices do not arise without a corresponding increase in debt and this is the root cause behind why housing credit growth remains well below trend. Demand for home loans is unlikely to improve until affordability improves and/or debt reduces. Affordability is unlikely to improve until prices fall or incomes rise.

- Lastly, the house price boom is the main reason (yes, there are others) why retail sales have remained well below the average experienced over the decade leading up the GFC. The housing bubble was fuelled by debt. Retail sales were artificially boosted during that time by households using part of that debt to fund additional expenditure. Without that stimulus, it is likely that retail sales will stay below the pre GFC average for a number of years. It is not that retail sales are too low now, it is just that they were unsustainably high before.

Conclusion

We expect domestic growth over the coming six months to remain moderate but uneven. The vast pipeline of mining investment projects under construction and the flow through effect for incomes continues to keep the unemployment rate low (+5.1%) and consumption in the mining states at elevated levels. In contrast growth in the non-mining states remains subdued, as the tourism sector and manufacturing industries struggle with the high Australian dollar, the building industry struggles with affordability issues (which are unlikely to be resolved in the short to medium term) and the financial services industry is impacted by the depressed state of financial markets. Lower interest rates though will assist indebted households and businesses.

Declining commodity prices and elevated global concerns means that the risk of the economy performing below trend are increasing.

This publication is issued by Moore Stephens Australia Pty Limited ACN 062 181 846 (Moore Stephens Australia) exclusively for the general information of clients and staff of Moore Stephens Australia and the clients and staff of all affiliated independent accounting firms (and their related service entities) licensed to operate under the name Moore Stephens within Australia (Australian Member). The material contained in this publication is in the nature of general comment and information only and is not advice. The material should not be relied upon. Moore Stephens Australia, any Australian Member, any related entity of those persons, or any of their officers employees or representatives, will not be liable for any loss or damage arising out of or in connection with the material contained in this publication. Copyright © 2011 Moore Stephens Australia Pty Limited. All rights reserved.