Overview

As we reach the end of the year, we thought to leave you with an important case touching on cartel behaviour, the exchange of information, and importantly, the careful consideration of whether and when to plead leniency and with what. We will host a breakfast session early in 2023 on the landscape for cartels with a particular focus on leniency and dawn raids. Watch this space.

On the case itself, on 17 November 2022, the Competition and Consumer Commission of Singapore ("CCCS") issued an Infringement Decision against four warehouse operators for engaging in anti-competitive agreements in violation of section 34 of the Competition Act 2004 ("Act"), and imposed a total financial penalty of close to S$3 million.

Specifically, the four warehouse operators, namely CNL Logistics Solutions Pte. Ltd. ("CNL"), Gilmon Transportation & Warehousing Pte. Ltd. ("Gilmon"), Penanshin (PSA KD) Pte. Ltd. ("Penanshin") and Mac-Nels (KD) Terminal Pte. Ltd. ("Mac-Nels") (collectively the "Parties") were found to have engaged in price fixing conduct by imposing in a coordinated manner an additional charge known as the "FTZ Surcharge" for warehousing services at Keppel Distripark. The FTZ Surcharge is a surcharge imposed on import cargo stored within the Free Trade Zone by warehouse operators.

CCCS' Investigation and Decision

In response to a complaint received from a member of the public, CCCS commenced an investigation on 8 August 2018. On 19 November 2019, CCCS conducted simultaneous inspections without notice (i.e. dawn raids) on 11 warehouse operators, including the Parties, that have warehouses located at Keppel Distripark. CCCS subsequently conducted interviews with, and obtained information and documents from the key personnel of the Parties.

CCCS' investigations revealed that the Parties coordinated the imposition of an identically named FTZ Surcharge at the same price of S$6 per weight/measurement on the same type of goods (i.e. import cargo) via physical meetings, emails, phone calls and WhatsApp conversations which occurred among them on 15 and 16 June 2017. The FTZ Surcharge imposed by CNL, Gilmon and Penanshin was effective from 1 July 2017, and Mac-Nels' FTZ Surcharge was effective from 1 August 2017.

Based on the evidence, CCCS concluded that the Parties had coordinated their pricing strategies instead of determining them independently. Such price fixing conduct had restricted price competition in the market for warehousing services. In particular, the Parties were aware that independently imposing the FTZ Surcharge could cause their customers to switch warehousing service providers, especially if their competitors did not impose such a charge. Accordingly, t he exchange among the Parties of their respective intentions to impose the FTZ Surcharge not only reduced their own uncertainty in deciding whether to impose the FTZ Surcharge but also put them in a stronger bargaining position with their customers to insist that their customers agree to the surcharge. CCCS observed that the Parties' decisions on whether to increase or impose new charges were heavily influenced by whether or not their competitors were also doing the same. It was also important for the Parties to prove to their own customers that their competitors were imposing the same surcharge, to increase the likelihood that their customers would accept the surcharge and not switch to another warehouse operator.

In the absence of the price fixing conduct, each Party may not have chosen to implement t he FTZ Surcharge or may have imposed it at a lower rate to avoid or reduce the risk of losing customers to other warehouse operators.

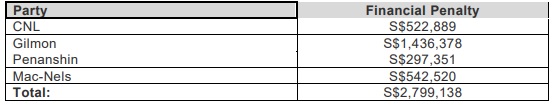

Therefore, CCCS considered that the price fixing conduct had as its object the restriction of competition and was, by its very nature, harmful to the functioning of normal competition. For infringing the section 34 prohibition against anti-competitive agreements, CCCS imposed the following financial penalties on the Parties:

In levying financial penalties, CCCS considered each business' relevant turnover, the duration of the infringement, the nature and seriousness of the infringement, as well as aggravating and mitigating factors.

With respect to the duration of the infringement, CCCS considered that the price fixing conduct occurred among the Parties lasted from 15 June 2017 to 19 November 2019, giving Parties the benefit of the doubt that the Parties had ceased the conduct following CCCS' inspections on 19 November 2019. Notably, CCCS refuted the Parties' claims that the infringement should be limited to the duration which the communication on the introduction of the FTZ Surcharge took place among the Parties, as the FTZ Surcharge was not specified to be for a fixed duration and continued to be imposed after the communication.

During the inspection, both Penanshin and CNL applied for CCCS' leniency programme which affords lenient treatment to businesses when they come forward to CCCS with information on their cartel activities. Where eligible for lenient treatment, businesses can be granted total immunity or be granted a reduction of up to either 100% or 50% in the level of financial penalties. In this case, Penanshin was granted a leniency discount due to the useful information and cooperation rendered, although the discount was less than 100% given that Penanshin had only made its leniency application after CCCS had made its investigations known to the Parties. While CNL was also a leniency applicant, CCCS assessed that it did not meet the requirements for leniency as it did not provide any useful or additional details of the cartel activity, and therefore did not grant CNL any leniency discount.

Comments

This infringement decision demonstrates that CCCS continues to actively investigate and enforce against cartel activities. It also follows after other recent cartel infringement decisions involving bid-rigging conduct over the last two years.

CCCS views price coordination with competitors as one of the most serious types of anti-competitive conduct as it removes the uncertainty in determining pricing strategies and results in customers getting less competitive prices. In times of inflationary pressures, CCCS has also emphasised that it is essential to safeguard competition to ensure that markets work well and choices are preserved. In this regard, CCCS actively pursues cartel cases involving anti-competitive agreements and possesses the power to impose on a party to an anti-competitive agreement, a financial penalty of up to 10% of the turnover of the infringing party in Singapore for each year of infringement, up to a maximum of three years. As such, it is critical for businesses to regularly review their activities and conduct employee training to ensure competition law compliance.

With the advent of online messaging platforms such as WhatsApp, it is common for employees to engage in more informal conversations and exchange of information with employees of competitors or business partners over such platforms. However, as demonstrated in this case and prior infringement decisions such as the 2019 infringement decision against exchange of commercially sensitive information among competing hotels, communications over such platforms can be reviewed by the regulator and treated as evidence of anti-competitive conduct. It is therefore important to ensure that employees receive proper training on the competition law risks and are alert to the fact that all communications, especially with competitors, must be treated with caution, even at informal social gatherings or via online messaging.

As further seen and exercised in this case, CCCS is empowered under the Act to undertake unannounced inspections (i.e. dawn raids) at the premises of businesses suspected of anti-competitive conduct. Dawn raids can be daunting for employees working on the ground and cause unnecessary panic. As such, businesses are advised to develop internal procedures and training to better prepare their employees for such situations. Employees should be able to respond effectively to dawn raids, including knowing who to contact and alert internally when faced with an unannounced inspection, requesting for a copy of the warrant, and knowing the company's rights in such situations (e.g. restricting access to legally privileged communications or documents).

In addition, as reflected by the difference in quantum of financial penalties imposed on Penanshin and that of the other three warehouse operators in this case, businesses involved in cartel conduct that apply for leniency early and provide quality evidence of high probative value may be granted a leniency discount on the financial penalty imposed by CCCS.

The extent of reduction in financial penalty is discretionary and will depend on the stage at whic h an undertaking comes forward, the evidence already in CCCS' possession and the quality of the information provided by the undertaking. Further, it should be noted that leniency treatment is not available to undertakings that initiated the cartel and undertakings that coerced other undertakings to participate in the cartel.

Given the above, it may be worthwhile for businesses to consider making a leniency application in the event they are involved in cartel conduct. Yet, the nature of the information they possess must be carefully reviewed before such a decision is arrived at.

Separately, it should be noted that the application for lenient treatment would require unconditional admission to the conduct for which leniency is sought. This may result in exposure to legal actions by third parties that may have suffered loss or damage as a result of the anti-competitive conduct in question. Depending on the nature of the anti-competitive conduct in question, this may also trigger competition authorities from other jurisdictions to commence an investigation. This is particularly so as confidentiality waiver clauses in leniency programmes have enabled competition authorities worldwide to exchange information and uncover large worldwide cartels. Therefore, businesses should carefully weigh the pros and cons of making a leniency application, based on the specific circumstances and risks at hand.

Conclusion

While businesses are free to adapt themselves intelligently to the existing and anticipated conduct of competitors, businesses must be familiar with the competition law prohibitions and their developments, including that in relation to anti-competitive agreements. To this end, this case serves as a reminder for businesses to avoid communicating with competitors, directly or indirectly, with a view of coordinating or influencing each other's commercial conduct on the market. Businesses must regularly review their activities and interactions with competitors, and provide sufficient training for their employees on competition law matters.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.