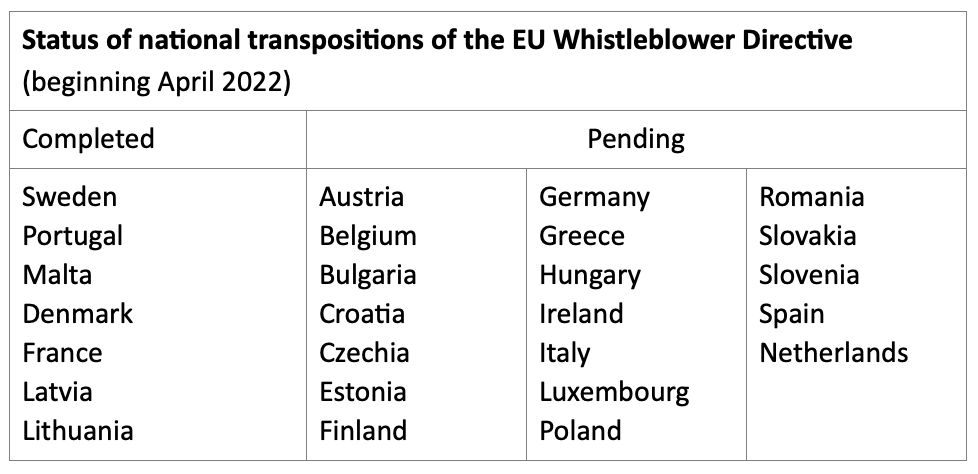

As we roll into the second quarter of 2022, we are starting to see more EU countries implement their national transpositions of the EU Whistleblower Directive. Slowly but surely!

And perhaps this gradual implementation will be a relief for companies that operate across EU borders. For, while the Directive is a step forward in moving member states towards a unified legal

framework for whistleblowing, each territory has the freedom to expand on the scope of requirements stipulated at the EU level – in fact, this has been encouraged by EU regulators. With the first handful of countries now complete this is exactly what is happening.

In this brief article we re-cap the basic requirements of the EU Directive, summarise the national nuances of those countries whose whistleblower protection laws have come into effect so far, and highlight the implications these may have for organisations in those countries.

Main requirements of the EU Whistleblower Directive

First of all, here's a quick reminder of the standard requirements of the EU Directive.

- A secure channel for receiving whistleblower reports must be put in place. Reporting must be possible in writing and/or orally, via telephone lines or other voice communications systems.

- Acknowledgment of the receipt of the report must be provided to the whistleblower within seven days.

- Feedback about the report follow-up must be given to the whistleblower within three months.

- An impartial person or department must be designated to deal with the reports, and reports must be followed up.

- Records must be kept of every report received, in compliance with confidentiality requirements.

- All processing of personal data must be done in accordance with the GDPR.

- Clear and easily accessible information must be available on the conditions and procedures for internal and external whistleblowing to competent authorities.

1. What's the definition of a whistleblower?

- According to the Directive: Reporting persons working in the private or public sector who have acquired information on breaches in a work-related context.

- Notable exceptions: Portugal has applied a broad definition of a whistleblower as "a natural person who publicly denounces or discloses an offense on the basis of information obtained in the course of their professional activity...".

- Challenges for organisations: How can we reach potential non-employee whistleblowers? Which languages should the reporting channel be available in? What channel works best for different stakeholders?

2. Which type of reporting channel is required?

- According to the Directive: Organisations must enable reporting in writing or orally, or both.

- Notable exceptions: In Sweden, reporting must be possible both orally and in writing.

- Challenges for organisations: Do we have capable recipients at all entities? Which roles are appropriate to receive reports? How can we train recipients so that we are compliant through all channels and entities? Can we bring together oral and written reports in one repository to gain an overview of potential hot spots?

3. What counts as a whistleblowing matter providing grounds for protection?

- According to the Directive: Breaches of Union law. Breaches of the Union's financial interests. Breaches related to internal market and tax evasion.

- Notable exceptions: Denmark counts infringements relating to "serious offences or other serious matters." In France "infringements relating to a threat or serious harm to the public interest are included. Sweden says that "a matter that is of public interest in the misconduct coming to light" can be reported, and Portugal has added "violent and/or organised crime" to the EU definition.

- Challenges for organisations: What shall we do with out-of-scope reports? Can we nonetheless gain value from them? What about reports that are not made in good faith? How do we find out about dissenting national regulations?

4. What are the requirements on facilitation of and rewards for whistleblowing?

- According to the Directive: Legal entities should provide information that allows for making an informed decision on whether, how and when to report. The EU Directive is silent on rewards.

- Notable exceptions: Under the Lithuanian whistleblowing law, a competent authority may grant compensation for whistleblowing reports.

- Challenges for organisations: To what degree do we need to communicate the whistleblower's rights? How much do we need to facilitate them? How should we reward whistleblowers?

5. Is anonymous reporting covered by the EU Whistleblower Protection Directive?

- According to the Directive: Power is delegated to the member states to decide whether legal entities in the private or public sector and competent authorities are required to accept and follow up on anonymous reports.

- Notable exceptions: Portugal has gone frombeing one of the last EU countries prohibiting anonymous reporting to one of the first to require the allowance of anonymous reporting.

- Challenges for organisations: Should we accept anonymous reports, even if we don't have to? In that case, how do we provide feedback to the anonymous reporter in compliance with the Directive?

6. What's the approach to Group/subsidiary whistleblower reporting?

- According to the Directive: Where a group comprises entities with 50 or more employees, each one of them must set up and operate its own internal channel.

- Notable exceptions: Organisations in Denmark may establish groupwide whistleblower schemes, unless the Minister of Justice overturns this ruling.

- Challenges for organisations: Are we compliant if we maintain various channels within one system?

As more differences emerge in the national transpositions of the EU Whistleblower Directive, monitoring and responding to these may create compliance complexity for larger organisations and those operating across borders within the EU.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.