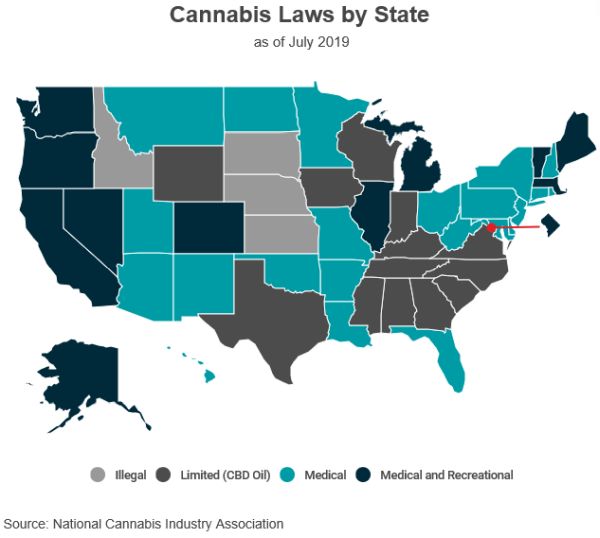

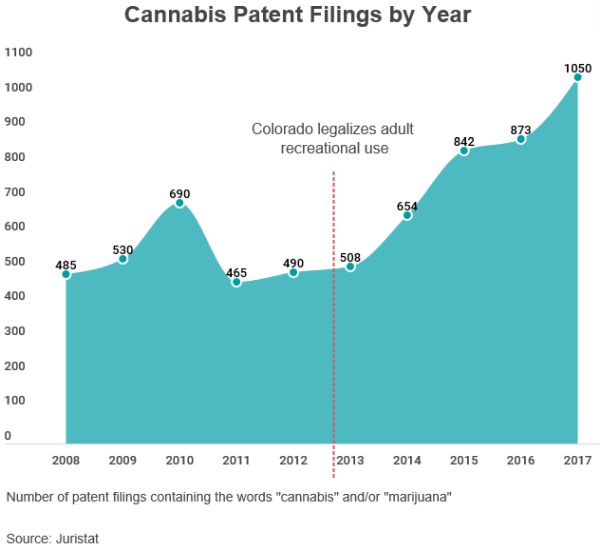

The past several years arguably have been some of the best for the cannabis industry since marijuana was originally criminalized in the early 20th century. As of the date of publication, marijuana is legal for medical use in 33 states and the District of Columbia, while it is legal for recreational use in 11 states and the District of Columbia. Its use for any purpose remains illegal at the federal level. The nationwide push toward wide-scale marijuana legalization began in 2012, when Colorado became the first state to legalize marijuana for recreational use, and has opened legitimate markets for marijuana entrepreneurs that did not exist only a decade earlier. The value of the legal cannabis market is now estimated at $10 billion and is only expected to grow as more states remove the legal barriers to entry.

As with any new and emerging market, entrepreneurs in the cannabis industry are eager to obtain intellectual property protection for their products to maximize their value. However, the patchwork of state laws regarding the legal status of cannabis, as well as inconsistencies between state and federal law on this topic, have rendered certain types of IP rights, particularly trademark rights, elusive for many cannabis entrepreneurs. But for companies wishing to obtain patent protection for their cannabis products, the path to IP protection is comparatively clear.

IP and the Controlled Substances Act

The Controlled Substances Act prohibits the possession, use, purchase, sale, or cultivation of cannabis, classifying it as a Schedule I substance — a category reserved for particularly dangerous drugs that have a high potential for abuse and no currently accepted medical use. Cannabis' illegal status at the federal level presents significant roadblocks primarily for entrepreneurs wishing to protect their business names, symbols, logos, and other trademarks. Because federal trademark registration is available only for goods that are "sold or transported in commerce," and selling or transporting cannabis in commerce is illegal at the federal level, trademark registrations for cannabis goods and services are de facto barred.

There is no such requirement in patent law, as Congress intended patentable subject matter to encompass "anything under the sun that is made by man." To obtain a patent, an applicant need only show that his or her invention concerns patentable subject matter and that it is new, useful, and non-obvious. The applicant's commercial use or planned commercial use of the invention claimed in the patent application has no bearing on its patentability. The USPTO is thus willing, with very few exceptions, to grant patents on any inventions that meet the legal requirements for patentability, including cannabis products.

The USPTO's Rich History of Cannabis Patents

Patent protection is available for a wide range of cannabis products, including new strains of the plant itself, although most cannabis patents concern "secondary" technologies such as cultivation methods, processing and extraction techniques, cannabis-derived products, consumption devices, and medical treatments. There are numerous examples of the USPTO's amenability to cannabis patents, as it has been granting them for many years. The office granted its first cannabis-related patent, titled "Isolation of cannabidiol" (U.S. Patent No. 2304669A), in 1942. Since then, it has issued a number of notable cannabis patents, including:

- U.S. Patent No. 6630507: Cannabinoids as antioxidants and neuroprotectants

- U.S. Patent No. 9095554: Breeding, production, processing and use of specialty cannabis

- U.S. Patent No. 8906429: Medical cannabis lozenges and compositions thereof

- U.S. Patent No. 9480647: Single serve beverage pod containing cannabis

- U.S. Patent No. 10172897: Enhanced smokable therapeutic cannabis product and method for making same

The Problem of Prior Art

The challenges facing cannabis entrepreneurs derive not from federal drug law, but from the comparative absence of prior art available in the industry. The cannabis industry is not "new" in the same way that other industries such as blockchain or augmented reality are new. It is has been functioning successfully, albeit illicitly, for decades. Even with the rapidly spreading legalization of cannabis for recreational use, the value of the black market still dwarfs that of the legal market. This creates a situation in which, prior to decriminalization, cannabis entrepreneurs who had developed innovative products were reluctant to publish their findings out of fear of criminal prosecution. The absence of well-developed prior art in the cannabis space raises the danger that the USPTO will issue invalid or overly broad patents due to this lack of available information or proof of prior use. Existing cannabis entrepreneurs in states that have decriminalized the industry can minimize the risk this poses to them through defensive publication.

Are They Enforceable?

Cannabis' legal status is not a significant challenge to patentability at the USPTO, but it is still unclear whether federal courts will be willing to enforce cannabis patent rights against alleged infringers. The first patent infringement case concerning a cannabis patent, United Cannabis Corp. v. Pure Hemp Collective, Inc., was filed in the District of Colorado in July of 2018. In that case, United Cannabis (UCANN) alleged that Pure Hemp's manufacturing and selling of a certain cannabinoid formulation infringed the claims of its patent (U.S. Patent No. 9,730,911), to which Pure Hemp responded by alleging that the claims of the '911 patent were invalid. Litigation in the case is ongoing but, thus far, neither the parties nor the court have raised the issue of cannabis' legality.

The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) took a similar approach in Insys Development v. GW Pharma Limited and Otsuka Pharmaceutical, (IPR 2017-00503), the first IPR decision concerning a cannabis patent. There, the PTAB did not raise the issue of cannabis' legality in either its decision to institute IPR or its final written decision, instead focusing on traditional issues common to all patents being challenged in that forum. These cases indicate that cannabis' Schedule I status does not necessarily bar patent litigants from the courts, but the real test of the courts' willingness to enforce cannabis patents is yet to come. Should the court in United Cannabis find that Pure Hemp's activities infringed, it remains to be seen whether it will order the defendant to pay damages for lost profits that were illegally obtained under federal law.

The opening of legal cannabis markets has launched a gold rush for innovative entrepreneurs while presenting investors with promising opportunities in a brand-new industry. This industry's success has faced little resistance from the USPTO, which has shown itself to be more than happy to grant patents on a wide variety of cannabis innovations. Rather, the primary risk facing cannabis patent applicants is the lingering cloud of uncertainty hanging over the federal courts, as judicial enforcement of cannabis patents remains an open question. Fish & Richardson will continue to monitor the rapidly evolving legal landscape surrounding cannabis patents and will keep our clients up to speed regarding any developments that could impact them.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.