On July 1, 2019, the Singapore High Court handed down its anonymized decision in BNA v BNB 2019 SGHC 142 ("BNA"). The case involved an application under section 10(3) of Singapore's International Arbitration Act ("IAA") requesting that the High Court decide whether an arbitral tribunal had jurisdiction to adjudicate the parties' dispute. In a decision that may have implications for similarly-drafted arbitration agreements, the High Court interpreted an express provision for "arbitration in Shanghai" to be an agreement to Singapore-seated arbitration with hearings in Shanghai, thereby upholding the validity of the arbitration clause and the jurisdiction of the tribunal. We summarize and discuss the High Court's decision below.

Background

The dispute arose out of a "Takeout Agreement" entered into between the plaintiff in the court proceedings (respondent in the arbitration) and two defendants (claimants in the arbitration) and governed by the laws of the People's Republic of China ("PRC"). Article 14.2 of the Takeout Agreement was the parties' arbitration agreement, and provided for SIAC arbitration "in Shanghai." Although not stated, it appears very likely from the decision that the parties were all PRC legal entities.

The defendants commenced arbitration against the plaintiff and a three-person tribunal was constituted. The plaintiff challenged the tribunal's jurisdiction, arguing that the arbitration agreement: (i) was invalid as a matter of PRC law because PRC law does not permit foreign arbitral institutions to administer PRC-seated arbitrations1 and (ii) may also fail the "foreign-elements test."2 The tribunal heard the challenge as a preliminary question. The majority held that the seat of arbitration was Singapore and that Singapore law governed the arbitration agreement. The majority thus ruled that it had jurisdiction to resolve the dispute, with Teresa Cheng, SC dissenting. Ms. Cheng took the view that: (i) the proper law of the parties' arbitration agreement is PRC law; (ii) the parties' dispute is classified under PRC law as a domestic dispute; and (iii) PRC law prohibits a foreign arbitral institution from administering the arbitration of a domestic dispute.

The plaintiff applied to the High Court under section 10(3) of the IAA, which permits parties to apply to the High Court to decide jurisdictional matters where a tribunal rules, as a preliminary question, that it has jurisdiction.

Applicable Principles Identified by the High Court

The Proper Law of the Arbitration Agreement: Critical to the High Court's decision was its determination of the proper law of the parties' arbitration agreement. The High Court explained that the Singapore courts had adopted the three-stage approach formulated by the English Court of Appeal in Sulamérica Cia Nacional de Seguros SA v Enesa Engelharia SA 2013 1 WLR 102 ("Sulamérica"), notably by the Singapore High Court in BCY v BCZ 2017 3 SLR 357 ("BCY"). The Sulamérica approach asks three questions:

- Have the parties made an express choice of law?

- If the parties have not made an express choice of law, have the parties made an implied choice of law?

- If the parties have not made an express or implied choice of law, with what system of law does their arbitration agreement have its "closest and most real connection"?

The Principles for Construing Arbitration Agreements: The High Court endorsed the approach to interpreting arbitration agreements set down by the Singapore Court of Appeal in Insigma Technology Co Ltd v Alstom Technology 2009 3 SLR(R) 936. The High Court identified the following principles for construing arbitration agreements:

- Principles for construing arbitration agreements are the same as those for construing any other commercial agreement.

- Courts should, as far as possible, construe an arbitration

agreement so as to give effect to a clear intention evinced by

parties to settle their disputes by arbitration. This principle

gives rise to two subsidiary principles:

- Courts should not construe arbitration agreements restrictively or strictly; and

- Courts should prefer a commercially logical and sensible construction over a commercially illogical one.

- A defect in an arbitration agreement does not automatically render it void ab initio, unless the defect is so fundamental as to negate the parties' agreement to arbitration.

The High Court emphasized that the objective of interpreting arbitration agreements is to prioritize party autonomy, rather than to insist on a clause's validity with "the nakedly instrumental objective of ensuring that the arbitration agreement is effective" (as the High Court put it at 48). The High Court found that the purpose of contractual interpretation of arbitration agreements is not "to divert the parties to arbitration come what may, without addressing directly the intentions of the parties" (BNA at 53).

The Doctrine of Separability: The High Court addressed the doctrine of separability, which is a tool of arbitration law that treats an arbitration agreement as distinct from the substantive contract containing it. In England, the application of the doctrine is limited to circumstances where the validity of the substantive contract is in question. Thus, the doctrine serves as a legal fiction created to preserve the parties' chosen mode of dispute resolution, even where the substantive contract is invalid, e.g., due to fraud, misrepresentation, incapacity, or some other defect in the formation of the contract. A natural consequence of the doctrine is that the governing law of the arbitration agreement is not necessarily always the same as the governing law of the substantive contract.

In BNA, the High Court found that the application of the doctrine of separability was not restricted in Singapore to circumstances in which the substantive contract is invalid. As such, the High Court held, the doctrine of separability could be used to save an arbitration agreement even where the purported defect was inherent to the arbitration agreement itself.

The High Court's Decision

The Seat of Arbitration: The High Court interpreted Article 14.2 to refer to two geographical locations: Shanghai and Singapore. It formed this view because Rule 18.1 of the SIAC Rules (2013) provides that Singapore shall be the seat of arbitration absent contrary agreement. The High Court held that by agreeing to use the SIAC Rules (2013), the parties had selected Singapore as the seat of arbitration. Because it was not possible to have two seats of arbitration, the High Court interpreted the agreement to "arbitration in Shanghai" to refer to the venue of arbitration (i.e., where hearings would take place). The High Court further emphasized that because Shanghai was not a law district, the reference to Shanghai was more naturally construed as a reference to venue than seat. The High Court thus found that the parties had selected Singapore as the seat and Shanghai as the venue.

The Governing Law of the Arbitration Agreement: The High Court found that there was no express choice of law because the choice of law clause (selecting PRC law) was separate from the arbitration agreement in Article 14.2. Adopting the approach in Sulamérica and BCY, the High Court found that the parties had impliedly selected PRC law as the governing law of the arbitration agreement by their selection of PRC law to govern the substantive contract. However, the High Court found that this implied choice was displaced by the fact that selection of PRC law to govern the arbitration agreement might render the agreement invalid under PRC law. As such, the High Court found that the law of Singapore—as the seat of arbitration—was the parties' implied choice of law governing the arbitration agreement.

Consequently, the High Court found that the arbitration agreement in Article 14.2 of the Takeout Agreement—being governed by Singapore law—was valid, and dismissed the plaintiff's application.

Commentary

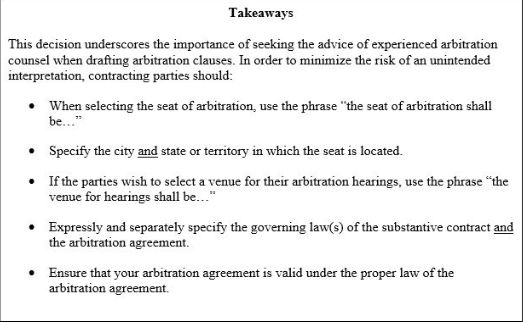

The logic behind the High Court's application of Rule 18.1 of the SIAC Rules (2013) to determine the seat in BNA is strained and threatens to have unintended consequences for future cases. The High Court appeared to treat Rule 18.1 as providing for a presumption that Singapore would be the seat of arbitration absent specific use of the word "seat," and was unconvinced that the wording of Article 14.2 ("arbitration in Shanghai") sufficed to rebut this presumption. In future arbitrations governed by the SIAC Rules (2013),3 the decision in BNA will invite jurisdictional arguments that the parties chose Singapore as the seat of arbitration where parties have failed (as is common) to use the specific word "seat" when selecting an alternative location.

The High Court's suggestion that the reference to "Shanghai" alone indicated an intention to specify venue does not sit well with commercial realities: as arbitration practitioners know well, it is not uncommon for parties to specify a major city as their seat without reference to the relevant state or territory (e.g., referring to "London" as opposed to "England"). Nothing conclusive can be gleaned from the fact that the parties in BNA referred to Shanghai instead of the PRC. The High Court's reasoning will invite jurisdictional arguments in future cases that a reference to a city (as opposed to a state or territory) does not constitute an agreement on seat.

Also problematic is the suggestion that the interpretation of an arbitration agreement can be dynamic. The High Court in BNA suggested that if the PRC had changed its laws after the execution of the Takeout Agreement to allow foreign arbitral institutions to administer PRC seated arbitrations, the arbitration would have proceeded on the basis that it was seated in the PRC with PRC law governing the arbitration agreement. This appears to be contrary to basic principles of contract law (i.e., that the court must assess the parties' intention at the time of contracting) and is fraught with uncertainty.

Given that Singapore prides itself on being a pro-arbitration jurisdiction, the High Court's inclination to find a means to affirm the tribunal's jurisdiction is understandable. However, in doing so, the High Court has tied itself in knots and relegated the parties' intentions to a secondary consideration. Its interpretation of Singapore as the seat of arbitration and Singapore law as governing the arbitration agreement simply does not sit well with the plain language of the Takeout Agreement, which shows clear choices of Shanghai as the place of arbitration and PRC law as the governing substantive law. This dissonance raises the specter of a successful challenge to enforcement outside Singapore under Article V(1)(a) of the New York Convention on the ground that the arbitration agreement is not valid under the law to which the parties have subjected it or under Article V(1)(d) on the ground that the arbitration procedure did not comport with the parties' agreement.

In order to promote efficient and effective dispute resolution, it is important that tribunals and courts engage in even-handed assessments of challenges to the validity of arbitration clauses, rather than diverting parties to arbitration come what may. International commercial arbitration does not operate within a closed domestic system: respondents disputing jurisdiction will typically have a second bite of the apple at the time of enforcement. The PRC courts have in the past proven skeptical of the creative pro-arbitration reasoning sometimes adopted in Singapore awards. Arbitration practitioners will remember well the PRC courts' refusals of enforcement in Alstom Technology Ltd. v. Insigma Technology Co. Ltd.4 and Noble Resources International Pte. Ltd v. Shanghai Good Credit International Trade Co., Ltd.5 due to concerns over perceived non-compliance with the parties' arbitration agreement.

The High Court has granted the plaintiff leave to appeal against its decision in BNA to the Singapore Court of Appeal. If appealed, it will be interesting to see how Singapore's apex court balances Singapore's pro-arbitration policy against the need for effective dispute resolution.

Footnotes

1 Article 10 of the PRC Arbitration Law requires that the establishment of all arbitral commissions be registered with a local judicial administrative department.

2 In fact, there is no express provision under PRC law prohibiting submission of domestic disputes to arbitration administered by non-Chinese arbitral institutions. However, Chinese courts have interpreted Article 271 of the PRC Civil Procedure Law and Article 128 of the PRC Contract Law (which permit submission of foreign-related disputes to foreign arbitral institutions) to prohibit submission of domestic disputes to arbitration administered by foreign arbitral institutions. See, e.g., Reply of the PRC Supreme People's Court for the Instructions Requested by the Beijing Higher People's Court re Beijing Chaoyang Sports and Leisure Company's Request for Recognition and Enforcement of a Korean Commercial Arbitration Board Award (2013) Min Si Ta Zi No. 64.

3 In contrast to Rule 18.1 of the SIAC Rules (2013), the 2016 edition of the SIAC Rules do not make Singapore the default seat. As such, the High Court's reasoning will not apply to arbitrations administered under the SIAC Rules (2016).

4 Reply of the PRC Supreme People's Court on the Request for Recognition and Enforcement of a Foreign Arbitral Award for the Applicant Alstom Technology Ltd. and the Respondent Insigma Technology Co. Ltd. (2012) Min Si Ta Zi No.54.

5 Noble Resources International Pte. Ltd v. Shanghai Good Credit International Trade Co., Ltd. (2016) Hu 01 Xie Wai Ren No. 1.

Because of the generality of this update, the information provided herein may not be applicable in all situations and should not be acted upon without specific legal advice based on particular situations.

© Morrison & Foerster LLP. All rights reserved