Arnold & Porter has played a key role in developing First Amendment doctrine that protects the rights of businesses, highlighted by the firm's 2011 Supreme Court victory in Sorrell v. IMS Health Inc. To help guide our clients on this important issue, we also monitor cases throughout the United States to track emerging trends. The latest case, out of the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, illustrates some of the issues arising in the lower courts after the Supreme Court's recent decision in National Institute of Family & Life Advocates v. Becerra (or NIFLA). The Ninth Circuit unanimously halted enforcement of a San Francisco ordinance requiring certain warnings on beverage advertisements. The eleven judges on the en banc panel, however, split four ways in their reasoning, and they especially disagreed over how to apply NIFLA. The Ninth Circuit's decision could be claimed as a victory by both regulators and businesses. The majority's narrow interpretation of NIFLA may prove useful for government entities seeking to regulate product packaging and advertising. But the court's unanimous disapproval of the ordinance bodes well for businesses seeking to challenge mandatory disclosures.

San Francisco's Beverage Warning

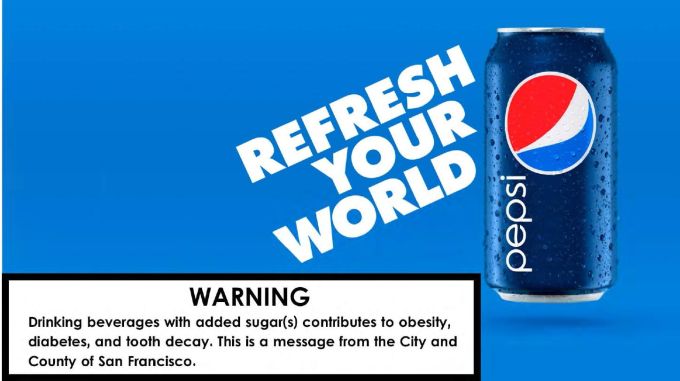

On January 31, 2019, the US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, sitting en banc, issued its long-anticipated ruling in American Beverage Association v. City & County of San Francisco. The Ninth Circuit halted enforcement of a San Francisco ordinance that would have required manufacturers to place a warning on advertisements for certain sugar-sweetened beverages. The warning needed to occupy at least 20% of the advertisement and be separated from the rest of the ad by a rectangular border:

WARNING: Drinking beverages with added sugar(s) contributes to obesity, diabetes, and tooth decay. This is a message from the City and County of San Francisco

Here are examples of what that warning would look like in practice:

Soon after San Francisco enacted the ordinance, industry groups sued and sought a preliminary injunction. The groups claimed that the required warning violated the First Amendment. A three-judge panel of the Ninth Circuit agreed and enjoined enforcement of the ordinance. A larger group of Ninth Circuit judges then voted to rehear the case en banc.

However, before the en banc argument occurred, the Supreme Court decided National Institute of Family & Life Advocates v. Becerra (or NIFLA), an important First Amendment case that struck down a statute requiring two types of compelled disclosures.

NIFLA first held that California could not force certain licensed pregnancy clinics to post notices that the state offered free or low-cost medical services, including abortions. Critically, NIFLA analyzed this notice as a content-based regulation of speech subject, meaning it was subject, at a minimum, to intermediate scrutiny. In doing so, the Court rejected two arguments in favor of reviewing the notice more deferentially. First, the notice did not simply compel the disclosure of "purely factual and noncontroversial" information, and so it was not covered by the more deferential standard for certain commercial disclosures set out in Zauderer v. Office of Disciplinary Counsel. Second, the notice did not "incidentally" regulate speech by way of regulating professional conduct; it regulated "speech as speech."

Though recognizing that content-based regulations were typically reviewed under the most rigorous "strict scrutiny," NIFLA declined to resolve whether that standard applied to the pregnancy-clinic notice, leaving open the possibility that regulations of "professional speech" should be treated differently under the First Amendment. The Court explained that resolving the precise standard of review was unnecessary because the required disclosure failed even under intermediate scrutiny: it was not appropriately tailored to further the state's asserted interest in informing low-income women about state-sponsored services.

NIFLA also held that the State could not require unlicensed clinics to post notices making clear that they were unlicensed. The "unlicensed" notice failed even under the more deferential standard from Zauderer because the Court found it "unduly burdensome."

The Ninth Circuit's Decision

Seven months after the Supreme Court's decision in NIFLA, the en banc Ninth Circuit decided American Beverage Association. The en banc court unanimously agreed that the beverage-advertising ordinance likely violated the First Amendment and thus could not be enforced. But the eleven judges divided sharply in their reasoning. The most significant disagreement was over how to apply NIFLA.

The majority opinion began by explaining that NIFLA had not changed the basic approach courts should take when evaluating commercial disclosure requirements like the advertising ordinance. In particular, the majority believed that NIFLA had left intact the Ninth Circuit's understanding of Zauderer. As the majority noted, Zauderer held that the state's interest "in preventing deception of consumers" allowed the state to require lawyers who advertised taking cases on contingency basis to disclose that clients may be liable for certain costs. Zauderer explained that, at least in that commercial context, mandating the disclosure of certain information created fewer constitutional problems than restricting or prohibiting that speech. The government could therefore require notices "containing factual and uncontroversial information about the terms under which his services will be available," so long as the notices are "not unjustified or unduly burdensome."

Because Zauderer focused on notices aimed to combat deception, courts subsequently had to decide whether its standard applied more broadly where the government was trying to achieve a different purpose. The Ninth Circuit had resolved that question in 2017, holding in CTIA-The Wireless Association v. City of Berkeley that "the prevention of consumer deception is not the only governmental interest that may permissibly be furthered by compelled commercial speech."

The majority in American Beverage Association did not believe that the Supreme Court's intervening decision in NIFLA undermined its 2017 holding in CTIA. Applying Zauderer and CTIA, the majority held that, regardless of whether the ordinance's required warning was purely factual or noncontroversial, it was invalid because the size and appearance of the required warning made it "unduly burdensome." The court cited expert testimony indicating that a smaller warning—one occupying only 10% of the advertisement—could have achieved San Francisco's stated objectives.

Splintered Reasoning

Three judges filed separate concurring opinions. In one concurrence, Judge Ikuta agreed that the ordinance was unduly burdensome and violated the First Amendment. But she strongly disagreed with how the majority analyzed the ordinance in light of NIFLA. Judge Ikuta believed that NIFLA "broke new ground on several key issues." Under her reading of NIFLA, any required commercial disclosure automatically qualifies as a "content-based restriction" on speech—and thus is subject to greater scrutiny under Supreme Court case law—unless it falls within a specific "exception" described in NIFLA. One such exception came from Zauderer: notices conveying "purely factual and uncontroversial information about the terms under which services will be available."

In Judge Ikuta's view, the beverage-advertising ordinance did not fall within the Zauderer exception for several reasons. First, the factual accuracy of the notice was disputed; indeed, the relationship between sugar and health was the subject of public debate. Second, the required notice related only to "the consumption of ... a product," not a service, and it did "not address the terms on which that product [was] provided." So while Judge Ikuta agreed with the majority that the ordinance was overly burdensome and failed for that reason, she also would have held that the compelled disclosure should have been subject to intermediate scrutiny because it was not a purely factual, uncontroversial message about the terms under which services will be available. She would have held that the ordinance failed intermediate scrutiny because, even assuming a "substantial state interest," the warning was both underinclusive (it did not apply to all sugar-sweetened products or all types of advertising media) and unnecessarily burdensome (San Francisco could have conveyed its message using "a less intrusive notice or a public health campaign").

Judge Ikuta also acknowledged that NIFLA had carved out another exception for "health and safety warnings long considered permissible." But she explained that this narrow exception was reserved for warnings with a historical pedigree dating back to the First Amendment's 1791 ratification. Warnings about sugar-sweetened beverages clearly did not qualify for that exception.

In another concurrence, Judge Christen, joined by Chief Judge Thomas, generally agreed with the majority that NIFLA did not require deciding whether a disclosure was purely factual and uncontroversial before turning to whether it was burdensome. Nevertheless, Judge Christen would have enjoined the ordinance because the message compelled was not purely factual, and thus would have avoided deciding whether the 20% size requirement made it overly burdensome.

In a third concurrence, Judge Nguyen explained that, because the targeted beverage advertisements were not false, deceptive, or misleading, Zauderer did not apply at all. Rather, she would have struck down the ordinance under the stricter standard laid out in Central Hudson Gas & Elec. Corp. v. Public Service Commission. She expressed concern that applying Zauderer's more forgiving standard to ordinances like San Francisco's "would lead to a proliferation of warnings compelled by local municipal authorities."

Practical Implications

American Beverage Association is a rare decision that can be claimed as a victory both by regulators wishing to impose commercial disclosure requirements and by the businesses subjected to those requirements.

On one hand, the reasoning of the majority opinion—especially when juxtaposed with Judge Ikuta's concurrence—may embolden government entities wishing to impose mandatory notices. Judge Ikuta's approach (which the majority did not follow) would have erected threshold hurdles for the government when trying to defend an ordinance like San Francisco's. Most significantly, Judge Ikuta would have given the ordinance heightened scrutiny because it related to the effects of consuming an advertised product, rather than the "terms" on which the product was being offered. By declining to adopt Judge Ikuta's approach, the majority may have been signaling that, even after NIFLA, the Ninth Circuit will continue to read Zauderer as covering a broad set of commercial disclosure requirements for services and products alike. Moreover, it could be argued that by not embracing Judge Nguyen's approach, the Ninth Circuit showed that it was sticking to its view that Zauderer applied to commercial disclosure requirements even when the government was not using the disclosure to combat fraud or deception.

On the other hand, the actual result of the case sets a strong precedent for businesses seeking to invalidate disclosure requirements. After all, the panel's 11 judges voted unanimously to invalidate the disclosure requirement, and 10 did so even under Zauderer's supposedly deferential standard of review. The decision especially calls into question mandatory warnings that are visually striking. The seven judges in the majority specifically found that the warning's size and rectangular set-off rendered it unduly burdensome, and they did so based on expert testimony suggesting that a smaller warning would have been effective. Also notable is the majority's refusal to consider whether the government could justify the warning under intermediate scrutiny; it held that the warning failed because it was too visually burdensome, regardless of the government's justifications. American Beverage Association is thus a potent precedent for businesses subject to mandatory warnings.

The fractured nature of the decision is also likely a preview of things to come in the other federal courts of appeals, and possibly in the US Supreme Court. Even before NIFLA, the judges of the Ninth Circuit were sharply divided over how to analyze commercial disclosure requirements, particularly those not enacted to prevent fraud or deceit. Its 2017 CTIA case featured notably strong dissents at multiple phases of the appeal. The four different opinions in American Beverage Association show NIFLA has not clarified the most important issues pertaining to compelled commercial speech: namely, (1) what standards of review should apply to which types of compelled disclosures, and (2) how exacting should those standards be.

Indeed, if anything, NIFLA drew into question what were previously settled principles in the Ninth Circuit. The same day the Supreme Court decided NIFLA, the high court ordered the Ninth Circuit to reconsider its decision in CTIA. The Ninth Circuit's reevaluation of its CTIA decision remains pending.

Questions about the level of protection the First Amendment affords against compelled commercial disclosures are likely to return to the US Supreme Court in the coming years. Commercial disclosure challenges are percolating across the country. Given that eleven Ninth Circuit judges produced four opinions on the topic, it seems inevitable that the courts of appeals will split with one another over the appropriate analytical framework for analyzing First Amendment questions arising out of compelled commercial speech.

Looking Around the Corner

The Ninth Circuit's decision leaves open a wide avenue for challenging required warnings. It bears directly on the constitutionality of proposed legislation in California that would require conspicuous "safety warnings" on containers for sugar-sweetened beverages and on machines that dispense them. The court's analysis could also have implications for other hot-button commercial disclosure issues, including the Trump administration's proposed requirement that drug companies disclose list prices in advertisements.

The firm will continue to monitor developments and plans to issue additional Advisories to keep you up to date.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.