INTRODUCTION

Commercial real estate collateralized loan obligations, or "CRE-CLOs," are growing in popularity as a way to securitize mortgage loans. Market participants have predicated as much as $14 billion of new CRE-CLO issuances in 2018, compared to $7.7 billion in 2017.

In many ways, CRE-CLOs are a more flexible financing option than real estate mortgage investment conduits (REMICs), the traditional vehicles for commercial mortgage-backed securitizations: unlike REMICs, CRE-CLOs may hold mezzanine loans, "delayed drawdown" loans, and "revolving" loans (and, in some cases, preferred equity), may borrow against a managed pool of assets, and may have more liberty to modify and foreclose on their assets. But structuring a CRE-CLO is not without challenges, and failing to properly structure a CRE-CLO could create adverse tax consequences for investors and could even subject the CRE-CLO to U.S. corporate tax.

This article discusses the tax considerations applicable to CRE-CLOs. Part II briefly explains what a CRE-CLO is. Part III discusses the overarching tax considerations relevant to CRE-CLOs and provides a brief overview of the two most common CRE-CLO tax structures—the qualified REIT subsidiary (QRS) and the foreign corporation that is not a QRS. Parts IV and V contain a more detailed discussion of each of these tax structures. Part VI describes the material benefits of using a CRECLO instead of a REMIC to securitize mortgage loans.

WHAT IS A CRE-CLO?

CRE-CLOs are special purpose vehicles that issue notes primarily to institutional investors, invest the proceeds mainly in mortgage loans, and apply the interest and principal they receive on the mortgage loans to pay interest and principal on the notes that they issue. CRE-CLOs allow banks, real estate investment trusts (REITs), and other mortgage loan originators to sell their mortgage loan portfolios, freeing up capital that they can then use to make or acquire additional mortgage loans. By issuing multiple classes of notes with different seniorities and payment characteristics backed by a pool of mortgage loans, CRE-CLOs appeal to investors that may not be willing or able to invest directly in mortgage loans.

OVERARCHING TAX CONSIDERATIONS

a Taxable Mortgage Pool Rules

Under the taxable mortgage pool (TMP) rules of the Internal Revenue Code, a vehicle (other than a REMIC) that securitizes real estate mortgages generally is treated as a TMP and taxed as a separate corporation for U.S. tax purposes if it issues two or more classes of "debt" with different maturities and the payment characteristics of each debt class bear a relationship to payments on the underlying real estate mortgages.

The TMP rules are intended to subject any net income recognized by a domestic mortgage loan securitization vehicle—i.e., the positive difference between interest accruals on the vehicle's assets, on one hand, and interest accruals on the vehicle's obligations, on the other hand—to U.S. net income tax. (If the vehicle is a REMIC, no entity-level tax is imposed, but holders of a special class of "residual interests" must pay this tax, and the "excess inclusion" rules discussed below prevent all or a portion of the taxable income from being offset or otherwise eliminated.)

Because CRE-CLOs typically issue more than two classes of notes, they generally will be TMPs.

b Avoiding Entity-Level Tax

As a condition to assigning a credit rating to any notes issued by a CRE-CLO, rating agencies typically insist that the CRECLO receive an opinion from U.S. tax counsel that the CRE-CLO "will not" be subject to an entity-level tax in the U.S.. Investors also expect this opinion, because a layer of corporate tax could dramatically reduce their investment returns.

Under Section 11(b), domestic entities that are treated as corporations for U.S. tax purposes generally are subject to a 21 percent net income tax. In addition, under Section 882, foreign entities that are treated as corporations for U.S. tax purposes are subject to U.S. federal income tax on any income that is "effectively connected" with the conduct of a "trade or business" within the U.S..

Accordingly, to avoid U.S. entity-level tax, CRE-CLOs generally are structured as one of the following:

- Qualified REIT Subsidiary (a

"QRS CRE-CLO") . REITs are a special type of domestic

corporation that invest predominantly in real estate assets,

including real estate mortgages, and generally can eliminate U.S.

corporate tax by distributing all of their net income to their

shareholders on a current basis. Because of their investment

strategy, REITs are common sponsors of CRE-CLOs.

- Under the REIT rules, if a REIT owns all of the equity interests in another corporation (which is referred to as a qualified REIT subsidiary, or "QRS"), then (absent an election otherwise) the QRS's assets, liabilities, and items of income, loss, and deduction are treated as the assets, liabilities, and items of income, loss, and deduction of the REIT itself. Thus, if a CRE-CLO is established as a QRS, then the CRE-CLO will not be subject to U.S. corporate tax, even if it is also treated as a TMP (i.e., even though it is a "QRS-TMP"). Instead, for U.S. tax purposes, the REIT is treated as the direct owner of the QRS's investment portfolio and is treated as pledging the portfolio as collateral for the notes that the QRS issues.

- To maintain its status as a QRS, a CRE-CLO must ensure that all of its "tax-equity" is beneficially owned by a single REIT.

- Foreign corporation that is not a QRS and is not engaged in a U.S. trade or business (non-QRS CRE-CLO) . CRE-CLOs that do not qualify as QRSs typically are organized in the Cayman Islands, which does not impose corporate income tax, and comply with "tax guidelines" to ensure that they are not engaged in a U.S. trade or business and thus are not subject to U.S. net income tax under Section 882. Although tax guidelines generally limit a CRE-CLO's origination and workout activities, a non-QRS CRE-CLO can issue tax-equity to outside investors (which a QRS CRE-CLO cannot do).

QRS CRE-CLOS: SPECIAL TAX CONSIDERATIONS

a Limitation on Issuing Tax-Equity

A QRS is a corporation whose "tax-equity" is 100 percent owned by a REIT. CRE-CLOs issue multiple classes of notes into the capital markets with different seniorities. Accordingly, in order to opine that a CRE-CLO "will not" be subject to an entitylevel tax in the U.S. on the basis that it is a QRS, U.S. tax counsel require a REIT to retain any classes of notes issued by the CRE-CLO that could be treated as equity for U.S. tax purposes—i.e., that do not receive an opinion that they "will" be treated as debt for U.S. tax purposes. This retention requirement is one of the most limiting downsides of using a QRS CRE-CLO

instead of a non-QRS CRE-CLO. (If the sponsor is not already a REIT, then creating and maintaining a REIT also may be a significant downside of using a QRS CRE-CLO.)

Whether an instrument is treated as debt or equity for U.S. tax purposes depends on the facts and circumstances on the instrument's issue date, and no one factor is determinative. One important factor is the reasonable likelihood of timely payment of principal and scheduled interest on the instrument.

A note's credit rating is generally viewed as indicative of its likelihood of repayment, and U.S. tax counsel typically do not opine that a class of notes will be treated as debt for U.S. tax purposes unless that class receives an investment grade credit rating—e.g., Baa3 or higher from Moody's, or BBB- or higher from Fitch. Accordingly, QRS CRE-CLOs generally may not issue below-investment-grade notes or equity to third-party investors. Instead, these interests must be retained by the REIT (or any entity disregarded into a REIT).

b Excess Inclusion Income

i Overview

REITs are treated as domestic corporations for U.S. tax purposes. As a result, U.S. tax-exempt investors generally are not subject to U.S. "unrelated business income tax" on dividends that they receive from a REIT. Non-U.S. investors generally are subject to 30 percent U.S. withholding tax on dividends that they receive from a REIT, but the amount of this withholding tax may be reduced by an applicable income tax treaty. In addition, as mentioned above, REITs generally can eliminate U.S. corporate tax by distributing all of their net income to their shareholders on a current basis.

However, when a REIT holds a REMIC residual interest, the REIT must allocate a certain amount of taxable income attributable to the REMIC residual interest, referred to as "excess inclusion income," among the REIT's shareholders in proportion to the dividends that the REIT pays. This excess inclusion income is subject to adverse treatment (as discussed below).

Similarly, Section 7701(i)(3) provides that, if a REIT holds a QRS-TMP, such as a QRS CRE-CLO, then the REIT's shareholders are subject to tax consequences "similar to" those that would apply if the REIT held a REMIC residual interest. Although the Internal Revenue Service has not issued regulations under Section 7701(i)(3), it has concluded that Section 7701(i)(3) establishes several basic principles, which apply even in the absence of regulations:

- First, the REIT must determine the amount of the QRS-TMP's excess inclusion income under "a reasonable method."

- Second, non-U.S. persons may not claim the benefits of an income tax treaty to reduce withholding on REIT dividends of excess inclusion income, and thus are always subject to 30 percent U.S. withholding tax on the excess inclusion income.

- Third, REIT dividends of excess inclusion income to tax-exempt shareholders are treated as unrelated business taxable income (UBTI). As a result, tax-exempt entities are subject to corporate tax on this portion of their REIT dividends.

- Fourth, taxable U.S. investors may not use net operating losses to reduce taxable income that is attributable to REIT dividends of excess inclusion income.

- Finally, the REIT must pay tax on any excess inclusion income that is allocable to governmental entities and other "disqualified organizations."

ii Excess Inclusion Income of a QRS-TMP

IRS Notice 2006-97 requires REITs to determine excess inclusion income attributable to a QRS-TMP using "a reasonable method." However, the tax code defines excess inclusion income only under the rules governing REMICs. REMICs issue multiple classes of regular interests, which are statutorily treated as debt for U.S. tax purposes and are paid down in sequence with principal collections on the REMIC's pool of mortgage loans, and one class of residual interests, which is the REMIC's "tax-equity" and is subordinated to the regular interests. The excess inclusion regime subjects a REMIC's net taxable income to U.S. income tax in the hands of the holder of the REMIC's residual interest.

Because REMIC regular interests are statutorily treated as debt for U.S. tax purposes, regardless of how little equity supports them, virtually all REMICs are structured so that their residual interests are non-economic, meaning that they do not receive any cash. The REMIC's most senior classes of regular interests provide for yields that are less than the weighted average interest rate of the pool of mortgage loans that the REMIC holds, while the REMIC's most junior classes provide for yields that are greater than the weighted average interest rate of the pool mortgage loans. Because the overall yield on the classes of regular interests issued by the REMIC in early years is less than the overall yield on the pool of mortgage loans its holds, a REMIC will have net taxable income in early years, and then (as the senior classes are paid down) will have net taxable losses in later years. Even though the REMIC's net taxable losses offset its net taxable income over time, the taxable losses are incurred in later years. Thus, in present value terms, a non-economic REMIC residual interest represents an economic liability, not an asset.

QRS-TMPs must have a significant amount of equity in order to be able to issue notes senior to the equity that receive an opinion of U.S. tax counsel that they "will" be treated as debt for U.S. tax purposes. As a result, QRS-TMP equity—unlike REMIC residual interests—always is entitled to cash distributions, and thus has positive value. If excess inclusion income attributable to a QRS-TMP were determined by treating the entire equity interest in the QRS-TMP as if it were a REMIC residual interest, the excess inclusion income would be significantly greater than if the QRS-TMP had made a valid REMIC election and had issued additional junior regular interests and a non-economic residual interest.

The legislative history to Section 7701(i)(3) suggests that Congress might, indeed, have expected the excess inclusion income attributable to a QRS-TMP to be determined by treating the QRS-TMP's entire equity interest as if it were a REMIC residual interest. On the other hand, Congress does not appear to have contemplated the widespread use of non-economic REMIC residual interests, and there is no readily apparent policy justification to require holders of QRS-TMP equity to report significantly greater excess inclusion income than holders of REMIC residual interests, particularly in light of the directive in Section 7701(i)(3) for the IRS to promulgate regulations taxing shareholders in a REIT that holds a QRS-TMP in a manner "similar to" shareholders in a REIT that holds a REMIC residual interest.

Accordingly, a "reasonable method" of determining excess inclusion income attributable to a QRS CRE-CLO may include treating the QRS CRE-CLO as a "synthetic REMIC," i.e., nominally treating a portion of the payments on the QRS's tax-equity as deductible solely for purposes of computing excess inclusion income, much like interest payments on a REMIC's belowinvestment- grade regular interests are deductible in computing the REMIC's overall net income Under this approach, the QRS CRE-CLO's equity is bifurcated into (1) one or more "synthetic" regular interests that are entitled to all cash-flows associated with the equity and has an issue price equal to its fair market value, and (2) a synthetic non-economic residual interest. The net taxable income attributable to the synthetic non-economic residual interest is calculated by permitting the synthetic REMIC to deduct (x) any interest that it actually pays or accrues on its notes, (y) any interest payments that it is deemed to pay or accrue on the synthetic regular interests, and (z) any other expenses of the QRS CRE-CLO to the extent that they would be deductible to a REMIC in computing the REMIC's taxable income. The result of this approach is that excess inclusion income attributable to the QRS CRE-CLO generally matches the excess inclusion income that would have been attributable to the QRS CRE-CLO's non-economic residual interest had the QRS CRE-CLO made a valid REMIC election. However, it is not certain whether this approach would be respected if challenged.

iii Blocking Excess Inclusion Income

As mentioned above, a REIT and its shareholders may be subject to adverse tax consequences as a result of the REIT's realization of excess inclusion income. REITs that wish to spare their shareholders from having any excess inclusion income will often create a "mini-REIT" to hold the QRS CRE-CLO tax-equity, and jointly own the mini-REIT with a wholly owned taxable REIT subsidiary (TRS).

Like a QRS, a TRS is a subsidiary of a REIT. Unlike a QRS, a TRS is treated as a separate corporation from the REIT. A REIT and its subsidiary must jointly elect for the subsidiary to be a TRS.

A TRS that earns excess inclusion income is subject to U.S. corporate tax (currently imposed at a 21 percent rate) on the excess inclusion income. Because the TRS earns and pays tax on the excess inclusion income, subsequent dividends by the TRS to the REIT should not be treated as excess inclusion income. The TRS thus "blocks" the excess inclusion income from reaching the REIT and its shareholders.

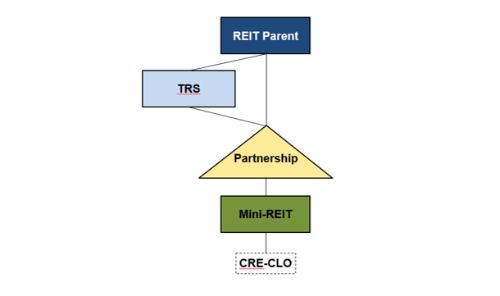

Because a CRE-CLO is treated as a QRS only if it is wholly owned by a REIT, bringing a TRS into the picture requires some additional tax structuring. Specifically, the REIT (which we refer to as the "REIT parent") invests in (1) a TRS and (2) a partnership. The TRS also invests in the partnership. The partnership's sole asset is the equity in a new entity that, itself, makes a valid election to be treated as a REIT (the "mini-REIT"). The mini-REIT owns the equity in the CRE-CLO.

This structure is illustrated below.

Because the mini-REIT owns all of the equity in the CRE-CLO, the CRE-CLO is eligible to be treated as a QRS. The mini- REIT realizes excess inclusion income from its ownership of the CRE-CLO, and dividends paid by the mini-REIT are tainted by any excess inclusion income. The partnership allocates the amount of any dividend income that consists of excess inclusion income to the TRS, and allocates all other dividend income directly to the REIT parent. Accordingly, only the excess inclusion income (and not the rest of the income attributable to the CRE-CLO's equity) is subject to corporate tax.

V NON-QRSCRE-CLOS: SPECIAL TAX CONSIDERATIONS

a Avoiding a U.S. Trade or Business

i Overview

As mentioned above, non-U.S. entities that are treated as corporations for U.S. tax purposes are subject to U.S. federal income tax on any income that is "effectively connected" with the conduct of a "trade or business" within the U.S.. The IRS asserts that "making loans to the public" within the U.S. (instead of purchasing the loans on the secondary market), whether directly or through a U.S. agent, constitutes a U.S. trade or business. Accordingly, tax guidelines for non-QRS CRE-CLOs typically have three overarching principles:

- The CRE-CLO may not negotiate the terms of a loan.

- The CRE-CLO may not be an original lender.

- The CRE-CLO may not be the first person to bear economic risk with respect to a loan.

These principles are predicated on the traditional view of a "lender" as the party that negotiates the loan, funds the loan, bears first risk with respect to the loan, and holds itself out as the lender.

A significant body of literature addresses the particulars of tax guidelines followed by "broadly syndicated" CLOs, which purchase small portions of broadly syndicated commercial loans. As a general matter, broadly syndicated loans are more liquid than mortgage loans, are not secured by real property, are originated by banks that are not related to the CLO, and are traded through electronic brokerage platforms. This article focuses on two issues that do not frequently arise for broadly syndicated CLOs, but commonly arise for CRE-CLOs because they invest in whole mortgage loans that their sponsor (or an affiliate of the sponsor) originated.

ii Sponsor-Originated Loans

REITs, loan funds, banks, and other sponsors commonly form CRE-CLOs to purchase mortgage loans that the sponsors originated, and delegate their own employees (or the employees of an affiliate) to make the CRE-CLOs' investment decisions. Because the sponsor expects to sell its loans to the CRE-CLO, and the CRE-CLO expects to buy loans from the sponsor, U.S. tax counsel must consider whether the sponsor could be viewed as having engaged in loan origination as an agent of the CRE-CLO, causing the CRE-CLO to be engaged in a U.S. trade or business. This analysis depends, in part, on whether the CRE-CLO holds a "static" or "managed" pool of mortgages.

1 Static CRE-CLOs

Some CRE-CLOs hold a "static" (non-traded) pool of mortgages and apply all principal collections on the mortgages toward paying down the notes that they issue (instead of using those principal collections to acquire new mortgages). An argument exists that these static CRE-CLOs are not engaged in a trade or business, but rather are "investors" for U.S. tax purposes, even if the sponsor's loan origination activities are imputed to the CRE-CLOs under an agency theory.

The distinction between a person that conducts mere investment activities (i.e., an "investor") and a person that is engaged in a business is that the former's activities are "more isolated and passive," whereas the latter's are "frequent, continuous, and regular." The number of purchases and amount and magnitude of activities associated with acquiring investments are usually less relevant under the existing trade or business authorities than the number of sales, and courts and the IRS have held that active asset management activities (which arguably would include loan negotiation) do not cause an investor to become a engaged in a trade or business. Under this view, even a CRE-CLO that directly originates loans should not be engaged in a trade or business so long as it holds the loans to maturity instead of selling them.

On the other hand, lending is an activity conducted by banks, financing companies, and other U.S. businesses, and the IRS and courts have found taxpayers to be engaged in a trade or business for purposes of Section 166 (relating to bad debt deductions) as a result of regularly and continuously making loans, even if the taxpayers retain and do not sell the loans. Moreover, some authorities have treated lending as a "service," although courts generally have held that the activity of making loans for investment and not for purposes of resale to a customer or otherwise to earn a spread is not a service.

Because there is no clear authority under Section 882 that making loans for investment does not constitute a trade or business, most static CRE-CLOs do not purchase loans from their sponsor if, at the time the sponsor originated the loans, the sponsor was committed to transfer the loans to the CRE-CLO. So long as the sponsor originates a loan without any preexisting commitment to transfer the loan to a CRE-CLO, the sponsor arguably cannot have originated the loan as an agent for the CRE-CLO, because it negotiated the terms of the loan, was the original lender, and was the first person to bear economic risk with respect to the loan. To bolster the argument that the loans were not originated with the expectation of transferring them to the CRE-CLO, some U.S. tax counsel prohibit the CRE-CLO from acquiring any loans that were originated earlier than the later of (1) some period of time (e.g., 90 days) before the CRE-CLO was formed, and (2) the date that the sponsor signed an engagement letter with its legal counsel to form the CRE-CLO.

2 Managed CRE-CLOs

The U.S. trade or business risk is more acute when the CRE-CLO is permitted to apply principal collections or sale proceeds to acquire mortgage loans on an ongoing basis. U.S. tax counsel often require some combination of the below features to ensure that the sponsor is not treated as originating loans as agent for the CRE-CLO after the CRE-CLO is formed.

- Seasoning period with arm's-length pricing. A significant waiting, or "seasoning," period between a loan's origination and a CRE-CLO's purchase of (or commitment to purchase) the loan helps ensure that the sponsor was the first person to bear economic risk with respect to the loan, which suggests that the sponsor is the true lender, and not an agent of the CRE-CLO. U.S. tax advisors often conclude that 90 days is a significant seasoning period on the basis that the loan market can change significantly during any 90-day period.

In addition, to ensure that the seasoning period in fact creates market risk for the sponsor, the sponsor must sell any loans to the CRE-CLO at arm's-length pricing. Some U.S. tax advisors require the CRE-CLO to appoint an independent investment advisor to confirm that each loan is purchased at its fair market value.

- Autonomy of origination business. Another factor that strongly supports the conclusion that the sponsor is not originating loans as agent for the CRE-CLO is if the sponsor can establish that it has the capacity to originate loans whether or not the CRE-CLO in fact acquires the loans and the sponsor negotiates and originates loans without input from the CRECLO's investment management team. To ensure that no particular loan is substantially certain to be acquired by the CRECLO at the time that it is originated, some U.S. tax advisors also place a significant percentage limitation on the aggregate face amount of sponsor-originated loans that the CRE-CLO can acquire.

- Incentive compensation. Some CRE-CLOs provide for a material part of their investment management team's compensation to be based on the CRE-CLO's performance. This factor arguably further helps to establish separation between the origination and management personnel.

3 Wholly Owned CRE-CLOs

One additional way that a CRE-CLO might establish that it is not engaged in a U.S. trade or business is if the sponsor owns all of the CRE-CLO's equity. Treasury regulations Section 1.864-4(c)(5)(i) provides that financing subsidiaries generally are not treated as engaged in the active conduct of a banking, financing, or similar business in the U.S.. However, a sponsor may not want to be required to retain all of the tax-equity of a non-QRS CRE-CLO.

iii Foreclosures

Under Section 897, a non-U.S. corporation's gain or loss from the sale or other disposition of a "United States real property interest" is subject to U.S. tax "as if the taxpayer were engaged in a trade or business within the United States during the taxable year and as if such gain or loss were effectively connected with such trade or business." A U.S. real property interest includes, among other things, real property located in the U.S. or the U.S. Virgin Islands.

Because substantially all of a CRE-CLO's assets consist of mortgage loans, there is a real risk that, at some point, a mortgage loan will default and the CRE-CLO will have the right to foreclose on the underlying real property. If the CRE-CLO is treated as a non-U.S. corporation for U.S. tax purposes and forecloses on U.S. real property, then it will be subject to U.S. federal income tax on any gain that it recognizes on a subsequent sale of that property, and will be required to file a U.S. federal income tax return.

The operative documents of many CRE-CLOs require the CRE-CLOs to isolate this tax and the U.S. federal income tax return filing obligation, in a U.S. "blocker" subsidiary. A blocker subsidiary should be respected as an entity separate from the CRECLO, and should not be treated as the CRE-CLO's agent, even though the CRE-CLO owns all of the equity interests of the blocker subsidiary. Thus, the blocker subsidiary, and not the CRE-CLO, is subject to U.S. corporate tax, and has to file U.S. federal income tax returns.

So long as a U.S. blocker subsidiary retains all of its earnings, it will not be required to withhold on dividends that it pays to the CRE-CLO. After the U.S. blocker subsidiary sells its assets, it can liquidate without having to withhold.

b Avoiding U.S. Withholding Tax

Under Section 882, interest on indebtedness paid by a U.S. person to a non-U.S. corporation is subject to 30 percent U.S. withholding tax unless the interest qualifies as "portfolio interest." U.S.-source interest received by a foreign CRE-CLO on a mortgage loan generally will qualify as portfolio interest if:

- the mortgage loan is in registered form; and

- the amount of the interest is not determined by reference to the obligor's income, profits, receipts, sales, or other cash flows, changes in the value of the obligor's assets, or distributions on the obligor's equity. A mortgage loan is in registered form if the right to receive payments of principal and stated interest on the loan may be transferred only through a book-entry system maintained by the obligor or its agent.

Mortgage loans sometimes contain an explicit requirement that the servicer, acting as an agent of the borrower, maintain a record of each lender and its assignees. This requirement ensures that the mortgage loans are in registered form.

If a mortgage loan does not contain this requirement, then a non-U.S. CRE-CLO may nevertheless eliminate the 30 percent U.S. withholding tax on interest payments made under the loan if it holds the loan through a domestic grantor trust. Under regulations Section 1.871-14(d)(1), interest received by a beneficiary from a grantor trust is treated as portfolio interest so long as the trust certificate held by the beneficiary is in registered form, even if the underlying obligations are not themselves in registered form. Accordingly, many CRE-CLOs hold their mortgage loans in a domestic grantor trust.

Very generally, a trust to which a person transfers property for the purpose of protecting and conserving the property for the transferor's benefit is treated as a grantor trust only if the trust has no "power to vary" the transferor's investment. A CRECLO's ability to trade the assets that it holds through a grantor trust might be construed as a power of the trust to vary the CRE-CLO's investment. However, because any transfer of assets into or out of the grantor trust may be effected only at the CRE-CLO's direction, the transfer should be treated in the same manner as (1) a liquidating distribution by the trust to the CRE-CLO, followed immediately by (2) the formation by the CRE-CLO of a new grantor trust. Thus, the CRE-CLO's ability to hold a managed pool of assets through a grantor trust should not cause the CRE-CLO to fail to qualify for the portfolio interest exemption.

c Concerns for REIT Sponsors

REITs typically do not form non-QRS CRE-CLOs.

First, REITs generally are prohibited from owning securities representing more than 10 percent of the total voting power or value of any one issuer, unless (i) the REIT owns 100 percent of the equity in that issuer and the issuer is a QRS, or (ii) the issuer is a TRS. Accordingly, owning 10 percent or more, but less than 100 percent, of the equity interests in a CRE-CLO could jeopardize a REIT's tax classification. If a REIT intends to own 100 percent of a CRE-CLO, then the REIT can form a QRS CRE-CLO.

Second, REITs are subject to a 100 percent "prohibited transactions" tax on any gain from a sale of property held for sale to customers in the ordinary course of a trade or business. There is a real risk that a REIT's ongoing sale of mortgage loans to one or more non-QRS CRE-CLOs would be treated as prohibited transactions. (The same concern exists if a REIT sells mortgages to one or more REMICs). By contrast, a REIT's transfer of mortgage loans to a QRS CRE-CLO is disregarded for U.S. tax purposes.

d. Converting a QRS CRE-CLO into a Non-QRS CRE-CLO

A QRS is not required to be a domestic entity in form. Instead, a Cayman Islands entity may be used. The Cayman Islands entity would be disregarded for U.S. tax purposes so long as it is a QRS.

If a REIT organizes a QRS CRE-CLO in the Cayman Islands, then the REIT might be able to sell the CRE-CLO's equity after a waiting period. Upon the sale, the CRE-CLO would become a non-QRS CRE-CLO. Because it is organized in the Cayman Islands, the CRE-CLO would not be subject to U.S. corporate tax unless it is engaged in a U.S. trade or business.

The waiting period must be sufficiently long for U.S. tax counsel to be able to conclude that the sale does not cause the REIT to be treated as a dealer and subject to the prohibited transactions tax described in Part V.c. In addition, U.S. tax counsel must be able to conclude that the non-QRS CRE-CLO will not be engaged in a U.S. trade or business (including, possibly, as a result of any loan originations that it conducted when it was still a QRS CRE-CLO) and that interest payments that the non- QRS CRE-CLO receives are not subject to withholding tax (i.e., the non-QRS CRE-CLO might need to contribute its assets to one or more domestic grantor trusts to avail itself of the portfolio interest exemption, as discussed in Part V.b.).

VI BENEFITS OF USING A CRE-CLO INSTEAD OF A REMIC

a Overview

Both REMICs and CRE-CLOs issue multiple classes of interests that are backed by a pool of mortgage loans. However, CRECLOs are more flexible than REMICs in several ways. This section briefly summarizes the most material differences between REMICs and CRE-CLOs.

b Static Pool

REMICs are subject to a 100 percent tax on "prohibited transactions," which include a disposition of a mortgage loan other than in very specific situations. As a result, REMICs do not trade their assets. By contrast, as discussed above, CRE-CLOs are permitted to have either "static" or "managed" pools of assets. Moreover, REMICs generally may not acquire new assets more than three months after their startup day, and are limited in their ability to invest in delayed drawdown loans or revolving loans, each of which require a holder to make advances on a periodic basis that are treated as new loans for U.S. tax purposes. By contrast, CRE-CLOs generally may invest in delayed drawdown loans or revolving loans.

c Limitations on Collateral

REMICs are required to invest almost exclusively in mortgage loans. By contrast, CRE-CLOs may invest in any assets, subject only to the following limitations:

- In the case of a QRS CRE-CLO, the asset must be an asset that the REIT is permitted to hold; and " In the case of a non-QRS CRE-CLO, ownership of the asset must not violate the CRE-CLO's tax guidelines (i.e., the non-QRS CRE-CLO must avoid being engaged in a U.S. trade or business).

Mezzanine loans and preferred equity generally are "good" REIT assets and do not violate tax guidelines, yet likely are not "qualified mortgages" under the REMIC rules. Accordingly, in addition to mortgage loans, CRE-CLOs generally may acquire mezzanine loans and QRS CRE-CLOs generally may also acquire preferred equity, while REMICs generally may not.

d Limitations on Modifications and Foreclosures

With very limited exceptions, REMICs may not acquire new assets more than three months after their start-up day. For U.S. tax purposes, a "significant modification" of a mortgage loan is treated as an exchange of the loan for a new loan. Accordingly, REMICs must be careful to ensure that none of the loans that comprise their assets is significantly modified unless the modification falls within one of several narrow safe harbors described in Revenue Procedure 2010-30. Moreover, even if a loan modification is not significant, the modification could still cause the REMIC to lose its REMIC status if it causes the mortgage to no longer be "principally secured" by an interest in real property. Finally, if a REMIC forecloses on a mortgage loan, the REMIC generally may not hold the foreclosure property for more than a three-year period (with a possible extension of up to three years).

By contrast, non-QRS CRE-CLOs generally are not subject to limitations on their ability to modify loans, other than any limitations that may be imposed by tax guidelines. In addition, as discussed in Part V.a.iii, CRE-CLOs (unlike REMICs) may acquire foreclosure property through a U.S. blocker corporation, and are not subject to any limitation on the amount of time during which they can hold the U.S. blocker corporation or the foreclosure property.

VII Conclusion

With careful tax planning, the two CRE-CLO structures discussed above can be powerful tools for securitizing pools of assets that are inappropriate for acquisition by a REMIC, for example, because the assets will be traded or will not consist solely of REMIC-eligible mortgages.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.