Commercial real estate collateralized loan obligations, or "CRE-CLOs," are growing in popularity as a way to securitize mortgage loans. Market participants have predicated as much as $14 billion of new CRE-CLO issuances in 2018,1 compared to $7.7 billion in 2017.2

CRE-CLOs are special-purpose vehicles that issue notes primarily to institutional investors, invest the proceeds mainly in mortgage loans, and apply the interest and principal they receive on the mortgage loans to pay interest and principal on the notes that they issue. CRE-CLOs allow banks, real estate investment trusts (REITs), funds and other mortgage loan originators to finance their mortgage loan portfolios, thereby freeing up capital that they can then use to make or acquire additional mortgage loans. By issuing multiple classes of notes into the capital markets with different seniorities and payment characteristics backed by a pool of mortgage loans, CRE-CLOs appeal to investors that may not be willing or able to invest directly in mortgage loans.

In many ways, CRE-CLOs are a more flexible financing option than real estate mortgage investment conduits, or REMICs, the long-reigning darling of commercial mortgage-backed securitizations. Unlike REMICs, CRE-CLOs may hold mezzanine loans, "delayed drawdown" loans, "revolving" loans (and, in some cases, preferred equity), may borrow against a managed pool of assets, and may have more liberty to modify and foreclose on their assets. But structuring a CRE-CLO is not without challenges, and failing to properly structure a CRE-CLO could create adverse tax consequences for investors and could even subject the CRE-CLO to U.S. corporate tax.

To avoid U.S. entity-level tax, CRE-CLOs generally are structured as either (1) a qualified REIT subsidiary, or QRS, or (2) a foreign corporation that is not a QRS. This article summarizes each structure.3

QRS Structure

QRSs are a creature of the REIT regime. A REIT is a special type of domestic corporation that invests predominantly in real estate assets, including real estate mortgages, and generally can eliminate U.S. corporate tax by distributing all of its net income to its shareholders on a current basis. Because of their investment strategy, REITs are common sponsors of CRE-CLOs.

Under the REIT rules, a QRS is a wholly owned subsidiary of a REIT whose separate existence is disregarded for U.S. tax purposes. Thus, if a CRE-CLO is established as a QRS, then the CRE-CLO will not be subject to U.S. corporate tax.

Limitation on Issuing Tax Equity

To maintain its status as a QRS, a CRE-CLO must ensure that all of its "tax equity" is beneficially owned by a single REIT. In other words, all interests issued by the CRE-CLO that are not indebtedness for tax purposes must continue to be owned by the REIT at all times.

One important factor in determining whether an instrument is treated as debt or equity for U.S. tax purposes is the reasonable likelihood of timely payment of principal and scheduled interest on the instrument. A note's credit rating generally is viewed as indicative of its likelihood of repayment, and U.S. tax counsel typically do not opine that a class of notes will be treated as debt for U.S. tax purposes unless that class receives an investment grade credit rating. Accordingly, QRS CRE-CLOs may not issue below-investment-grade notes or equity to third-party investors. Instead, these interests must be retained by the REIT (or an entity disregarded into a REIT).

Mitigating the Excess Inclusion Rules

Very generally, a REMIC's most senior classes of economic interests provide for yields that are less than the weighted average interest rate of the pool of mortgage loans that the REMIC holds, while a REMIC's more junior classes of economic interests provide for yields that are greater than the weighted average interest rate of the pool of mortgage loans. Because the overall yield on these interests in early years is less than the overall yield on the pool of mortgage loans, a REMIC will have net taxable income in early years followed by net taxable losses in later years.

The REMIC rules generally ensure that someone pays tax on all or a portion of a REMIC's net taxable income, which is referred to as "excess inclusion" income. Consistent with this policy, because QRS CRE- CLOs (like REMICs) are not subject to entity-level tax, the tax code imposes material adverse tax consequences on a REIT and its shareholders (including otherwise tax-exempt shareholders) to the extent that dividends paid by the REIT are attributable to excess inclusion income of a QRS CRE-CLO.

IRS guidance requires REITs to determine the amount of excess inclusion income that is attributable to a QRS CRE-CLO using a "reasonable method." In the absence of further guidance, many tax advisers have concluded that a reasonable method includes treating the QRS CRE-CLO as a "synthetic REMIC," i.e., nominally treating a portion of the tax equity of the QRS as deductible, solely for purposes of computing excess inclusion income, much like a REMIC issues below-investment-grade regular interests, which are deductible (by statute) in computing a REMIC's overall net income. Under this approach, the excess inclusion income attributable to a QRS CRE-CLO more closely matches the excess inclusion income that would have been attributable to the QRS CRE-CLO had it made a valid REMIC election. However, it is not certain whether this approach would be respected if challenged.

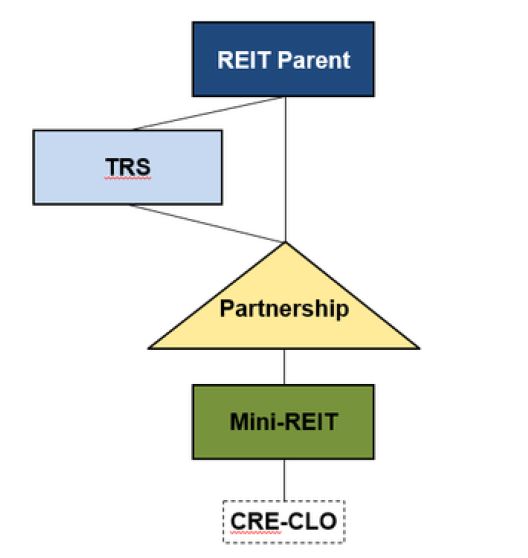

REITs that wish to spare their shareholders the risk of any excess inclusion income will often create a "mini-REIT" to hold the QRS CRE-CLO's tax equity, and jointly own the mini-REIT with a taxable REIT subsidiary, or TRS. A TRS may be a wholly owned subsidiary of a REIT but, unlike a QRS, elects to be treated as a separate corporation from the REIT. A TRS that earns excess inclusion income is subject to U.S. corporate tax on the excess inclusion income; however, subsequent dividends by the TRS to the REIT are not treated as excess inclusion income. The TRS thus "blocks" the excess inclusion income from reaching the REIT and its shareholders.

This structure is illustrated below.

Because the mini-REIT owns all of the equity in the CRE-CLO, the CRE-CLO is eligible to be treated as a QRS. The mini-REIT realizes excess inclusion income from its ownership of the CRE-CLO, and dividends paid by the mini-REIT are tainted by any excess inclusion income. The partnership allocates the amount of any dividend income that consists of excess inclusion income to the TRS, and allocates all other dividend income directly to the REIT parent. Accordingly, only the excess inclusion income (and not the rest of the income attributable to the CRE-CLO's equity) is subject to corporate tax.

Non-QRS Structure

A CRE-CLO sponsor may choose not to use the QRS structure, for example, because REIT compliance is expensive, the sponsor is too closely held to qualify as a REIT, or the sponsor needs the flexibility to sell or freely finance the "tax equity." CRE-CLOs that do not qualify as QRSs and that issue two or more classes of notes are statutorily treated as corporations for U.S. tax purposes under the so-called "taxable mortgage pool" rules of the tax code. To avoid U.S. corporate tax, these CRE-CLOs typically are organized in the Cayman Islands, which does not impose corporate tax.

Cayman Islands corporations are subject to U.S. corporate tax only on income that is "effectively connected" with a "U.S. trade or business" for U.S. tax purposes. The IRS asserts that "making loans to the public" (instead of purchasing the loans on the secondary market), whether directly or through a U.S. agent, constitutes a U.S. trade or business. Because sponsors of CRE-CLOs often form the CRE-CLOs with the expectation of selling loans to them, non-QRS CRE-CLOs must follow special "tax guidelines" to ensure that the sponsor is not viewed as having engaged in loan origination as an agent of the CRE-CLO, causing the CRE-CLO to be engaged in a U.S. trade or business.

Although the precise contours of a CRE-CLO's tax guidelines often depend on the internal operations of the sponsor, U.S. tax counsel typically require some combination of the below features to ensure that the sponsor is not treated as originating loans as agent for the CRE-CLO:

- Seasoning Period With Arm's-Length Pricing. A significant waiting, or "seasoning," period between a loan's origination and a CRE-CLO's purchase of (or commitment to purchase) the loan helps ensure that the sponsor is the first person to bear economic risk with respect to the loan, which suggests that the sponsor is the true lender, and not an agent of the CRE-CLO. U.S. tax counsel often conclude that 90 days is a significant seasoning period on the basis that the loan market can change significantly during any 90-day period.

In addition, to ensure that the seasoning period in fact creates market risk for the sponsor, the sponsor must sell any loans to the CRE-CLO at arm's-length pricing. Some U.S. tax advisers require the CRE-CLO to appoint an independent investment adviser to confirm that each loan is purchased at its fair market value.

- Autonomy of Origination Business. Another factor that strongly supports the conclusion that the sponsor is not originating loans as agent for the CRE-CLO is if the sponsor can establish that it has the capacity to originate loans whether or not the CRE-CLO in fact acquires the loans and the sponsor negotiates and originates loans without input from the CRE-CLO's investment management team. To ensure that no particular loan is substantially certain to be acquired by the CRE-CLO at the time that it is originated, some U.S. tax advisers also place a significant percentage limitation on the aggregate face amount of sponsor-originated loans the CRE-CLO can acquire.

- Incentive Compensation. Some CRE-CLOs provide for a material part of their investment management team's compensation to be based on the CRE-CLO's performance. This factor arguably further helps to establish separation between the origination and management personnel.

Conclusion

With careful tax planning, the CRE-CLO structures discussed above can be powerful tools for securitizing pools of assets that are inappropriate for acquisition by a REMIC, including assets that will be traded or will not consist solely of REMIC-eligible mortgages.

Footnotes

1 Cathy Cunningham, CREFC 2018: Say Hello to CLOs, Commercial Observer (Jan. 11, 2018), available at https://commercialobserver.com/2018/01/crefc-2018-say-hello-to-clos.

2 New Sponsors to Lift CLO Volume This Year, Commercial Mortgage Alert (Feb. 9, 2018), at 1.

3 Special rules known as the taxable mortgage pool rules treat CRE-CLOs as corporations by statute, thus preventing CRE-CLOs from being structured as partnerships for tax purposes.

Originally published in Law360

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.