On April 11, 2012, the Financial Stability Oversight Council (the "Council") gave more shape to the framework of systemic risk regulation by publishing a final rule (the "Rule") that sets forth the process for the designation of nonbank financial institutions as systemically important.1 Once designated, these systemically important financial institutions ("SIFIs") will be supervised by the Federal Reserve Board (the "Board") in much the same way that it supervises bank holding companies with $50 billion or more in consolidated assets. This supervision will involve the use of more rigorous "enhanced prudential standards" than apply to bank holding companies below the $50 billion floor. The Board proposed such standards earlier this year. Large nonbank financial companies should review the Rule with care, given the onerous consequences of designation and the intricacies of the designation process.

The designation of nonbank financial firms as SIFIs is one tool, but perhaps not the most efficient tool, for addressing systemic risk in the financial services industry. The Dodd-Frank Act Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act ("Dodd-Frank" or the "Act") provides two other tools: the identification and regulation of systemically risky activities across all financial institutions and authority to resolve distressed SIFIs in an organized manner outside the bankruptcy and bank receivership processes.

Because many firms are likely to engage in any given line of business that presents a high level of risk, the identification and regulation of these activities across the financial services industry is the most effective way to address systemic risk. The regulators will be able to collect information on how several firms operate the business and manage the attendant risks, which will enable the regulators to establish a sophisticated industry-wide approach. By contrast, the designation of particular firms will focus on idiosyncrasies and unique risks to financial stability that can only be handled on an institution-specific basis. This approach will create at best a materially smaller body of knowledge that can be applied to the regulation of other large firms. Nevertheless, the Council has chosen to concentrate on the designation of nonbank financial firms as presenting threats to U.S. financial stability. The review of activities that may lead to systemic risk seems to be a lower priority.

Important consequences will flow from designation as a SIFI. Designation would adversely affect the ability of these institutions to compete with their undesignated competitors due to increased costs and supervisory impact on their decision making process. Under the Rule, a significant number of large financial firms could be pulled into the Council's designation process. The Rule establishes quantitative thresholds to identify firms subject to the process, which appear to be at least in part "reverse engineered" based on experiences from the financial crisis. However, the metrics would also sweep up firms that would pose widely divergent levels and types of risk to financial stability, including many firms that do not warrant designation. Moreover, the Council has made clear that the universe of covered firms may go beyond those firms that meet the quantitative thresholds.

The Council has declined to provide any kind of exemption or safe harbor for sectors of the financial services industry that would seem to present no real threat to financial stability, either because regulation of particular activities would more effectively and more equitably address any risks posed, or because the bank holding company model would not effectively address any risks posed.

The uncertainties in the process and the consequences strongly suggest that firms that would exceed any of the specified metrics, as well as other financial firms that could be viewed as presenting risks to financial stability, develop a strategy to take the initiative in addressing the Council's likely concerns based on the information in the Rule, and as discussed more fully below. This paper explains the basis for and the elements of such a strategy. Attached are two annexes, one a detailed analysis of the Rule and the other a description of a related rulemaking by the Board on the definition of "predominantly engaged in financial activities."2

Overview of the Rule

The Rule contemplates that the Board supervise those financial firms that may disrupt the U.S. financial system as a result of either their threatened failure or the nature and scope of their activities. The Council sees primarily three types of threats that could create such disruption: (i) exposures of third parties to the firm such that an adverse event at the firm could "materially impair" those third parties; (ii) reliance on short-term funding or other actions that would require the firm, if troubled, to liquidate its assets quickly in a volume and at prices that would disrupt trading or funding across the markets; and (iii) the disappearance of or diminution in critical financial functions that other market participants could not replace when the firm withdraws from the market.

The process that the Council will use to designate the nonbank financial firms that could pose one or more of these threats involves the identification of a potentially large group of institutions—that part of the process known as Stage 1—followed by a winnowing-out process— referred to as Stages 2 and 3.

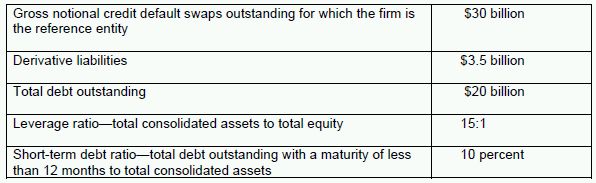

The universe of firms that will be subject to the Council's designation process includes—but is not limited to—firms with more than $50 billion in total worldwide consolidated assets that cross at least one of the five quantitative thresholds in the table below.

These thresholds appear to be designed to identify firms with more than $50 billion in consolidated worldwide assets with a higher risk of failure or, to a lesser extent, a higher risk to counterparties if they should fail.

Nonbank financial firms that do not meet either the $50 billion threshold or any of the other thresholds are not necessarily home free. The Council has reserved its authority to place other nonbank financial firms in Stage 2 and has said that the fact that a nonbank financial firm does not meet the thresholds does not mean that it will not be designated as systemically important. In the supplementary information to the Rule, the Council observes that it may wish to assess the systemic risks associated with certain firms that do not currently disclose information that is sufficient to take the necessary measurements.

The thresholds do not necessarily reflect real risks to financial stability. For example, as to risks, an institution with $50 billion in total worldwide assets and only $20 billion in debt outstanding could have a tier 1 leverage ratio of 60 percent and conservative investments as assets. Further, the holders of the debt could be so many and so diverse that the remote possibility of failure of the firm would pose virtually no risk of domino failures of financial firms that could threaten paralysis of the financial system. Although such a firm should be eliminated from the designation process fairly readily, other firms that may be viewed as presenting higher levels of risk will want to be in a position to address the potential designation process.

Moreover, the thresholds already are in a state of flux. In the supplementary information to the Rule, the Council said that it anticipated revising the threshold for derivative liabilities once the Commodity Futures Trading Commission ("CFTC") and the Securities and Exchange Commission ("SEC") have finalized the definitions of "major swap participant" and "major security-based swap participant" to address potential future exposures. Since then, the two agencies have released a joint final rule on these definitions.3 An element of the definitions is whether the participants hold "substantial positions" in different kinds of swaps. Whether these position thresholds will constitute another quantitative threshold for Stage 1 remains to be seen. The Council also expects to rely on the new Forms PF that hedge funds and private equity funds will be required to file with the SEC. For asset management firms, the Council is still considering whether these firms in general could pose a threat to financial stability and, if so, what the appropriate metrics would be. Firms will want to consider how the resolution of these issues will affect their relationships to the stated thresholds.

A firm that meets the stated thresholds in Stage 1 automatically enters Stage 2. The Council may place other firms in Stage 2 as well. The nature of Stage 2 would suggest that the Council will or should notify a firm at least informally that it has entered Stage 2, but the Rule offers no assurance that it will do so. In this stage, the Council will begin to undertake a companyspecific review of the risks posed by the firm. The Council will apply six categories of factors: interconnectedness, substitutability, size, leverage, liquidity and maturity mismatch, and existing regulatory scrutiny. Each factor has several qualitative and quantitative elements. As we discuss further below, firms should keep in mind the relationship between these six factors and the threats of credit risk to counterparties, disruption of markets due to liquidation of assets and loss of critical functions.

Among these factors, interconnectedness clearly relates to counterparty credit risk while substitutability appears to relate to loss of critical functions. Size relates to interconnectedness as well as potential for market disruption. Size also affects loss of critical functions although perhaps less directly. Leverage, liquidity, maturity mismatch and existing regulatory scrutiny relate to the likelihood of a problem at a firm more than to the consequences of the problem.

The distinction between likelihood and effect is important. Likelihood of a problem is an issue that may be common to markets or business line,s and logically should be dealt with through more general regulatory and supervisory regimes. If these issues are addressed appropriately under existing regulatory and supervisory regimes or Section 120, the need to designate individual institutions on the basis of such factors should be greatly reduced.

The Stage 2 and Stage 3 reviews are a continuum but differ in the sources of the information that the Council considers. In Stage 2, the Council will rely on public information and material available from the firm's regulators that has been analyzed by the Treasury Department's Office of Financial Research ("OFR"). If the Council believes that this information is insufficient to make a determination of a firm's possible threat to financial stability, it will move the firm to Stage 3, where it will request, through OFR, and take into account, information from the firm.

A firm's participation in Stage 2 is not entirely clear. In the supplementary information to the Rule, the Council describes Stage 3 as the time for a firm's active participation in the designation process. Yet the Rule provides that the Council may review material provided by a firm in Stage 2.4

The Council may choose not to place a large nonbank firm into Stage 3, evidently satisfied on the basis of public and supervisory information that the firm does not present systemic risk. Nevertheless, the Council regards a decision not to move a firm into Stage 3 as "preliminary" and does not plan initially to notify firms that they have not been moved to Stage 3. Such firms will be left in limbo, apparently in perpetuity.

Stage 3 is the formal part of the process and includes specific deadlines. Once the Council decides that it needs information from a firm directly, it will issue a Notice of Consideration, which will include a request for information. The request may be wide ranging, and the Council has not indicated what a request is likely to cover. Once the Council believes it has a full record on which to make a designation, it will issue a Notice of Proposed Determination. Upon receipt of this notice, a firm will have 30 days in which to request a hearing. The Council will then set a time for a hearing within 30 days of the firm's request, and this date will serve as a deadline for the submission of relevant information. If the firm does not request a hearing, the Council will render a decision within 40 days of the firm's receipt of the Notice of Proposed Determination— meaning that the firm will have substantially less time to prepare and submit information if it does not request a hearing. If the Council determines that it will designate a firm as systemically important, it will give the firm one day's advance notice before releasing a final determination so that the firm can prepare appropriate disclosures, releases, or other communications. The firm has a right to judicial review, whether or not it has requested a hearing and one has taken place.

Public statements by Treasury Department officials indicate that the Council is likely to designate its first SIFIs before the end of 2012. In order to do so, given the time periods in Stage 3, the Council will need to issue Notices of Consideration early in the summer.

The Rule describes Stages 2 and 3 as seriatim events, but the Council's evaluation of a particular firm could result in a slightly different process. For example, the Council may decide at the outset that its decision will be governed by information held by the firm and issue a Notice of Consideration at an earlier point than with respect to other firms. Alternatively, the Council could decide, solely on the basis of Stage 2 information, that it intends to designate a firm as systemically important and that an information request is unnecessary. In this event, the Council could issue a Notice of Proposed Determination without a prior Notice of Consideration.

The only public disclosure that the Council will make is the publication of the final designation.

The "Predominantly Engaged" Rulemaking

Implementation of the Rule is linked to a separate and ongoing rulemaking by the Board on the meaning of "predominantly engaged." Section 113 limits the designation process to "nonbank financial companies," a term that, under section 102(a)(4), includes only those companies that are "predominantly engaged in financial activities." The Board is charged with implementing this term through rulemaking. Section 102(a)(6) requires that the Board's regulation include two tests—that a firm is predominantly engaged when 85% of its assets or revenues are derived from activities permitted to financial holding companies.

Currently pending is a proposed rule from the Board that remains open for comment.5 Annex 2 describes the rulemaking in detail. In light of the complexity both of accounting rules and of the structure of many large nonbank firms, firms with material non-financial business should carefully review how the proposed rule attributes assets and revenues to financial and nonfinancial operations. This mapping process may require significant time and resources, particularly for firms that are not required to use U.S. generally accepted accounting principles.

Finalization of a rule interpreting "predominantly engaged" is not, in the Council's view, essential to the designation process.6 The Council apparently will begin its process before the Board has issued its final rule. This procedure may not matter for firms that are clearly predominantly engaged but firms near to the line could be put to substantial expense addressing a potential designation for no reason. Moreover, as we explain in Annex 2, we believe that the Council does not, as a matter of law, have the authority to designate a nonbank firm as systemically important without the Board's final rule that describes which firms may be subject to the designation process. Notwithstanding this principle, it is likely that the Council has already begun to review certain nonbank financial firms for designation.

Preparation

Every nonbank financial firm with consolidated assets of more than $50 billion or that does not meet that threshold but that either meets one of the other thresholds or that has reason to believe that the Council could designate it on a qualitative basis, should develop a strategy for addressing the designation process. Three considerations drive the need for a strategy.

First, the Council has not limited itself to those firms that exceed the quantitative thresholds. Firms that approach or exceed the thresholds are, of course, at the greatest risk of designation and have an attendant greater need for a strategy to address designation. The Council has identified private equity funds, and hedge funds as firms that may be subject to designation, even if they do not meet any of the quantitative thresholds. A firm that provides a specialized but critical product or that dominates a particular product or service market where there are relatively high barriers to entry may be subject to the process as well.

Second, once a large firm meets one of the thresholds, the process may begin to gain momentum towards a designation of systemic importance. Entry into Stage 2 is automatic, and the Council appears loathe to remove a firm from consideration solely on the basis of the Stage 2 review. Further, the amount and quality of the regulatory information on different types of financial firms may vary, reinforcing the Council's inclination to undertake Stage 3 reviews. Nevertheless, it is not clear that a concentrated effort to educate the Council's staff on why a firm should not be designated would receive appropriate attention.

Third, designation, or even the perception that designation is likely, may have a material effect on a nonbank financial firm's earnings and operations. Section 113 requires that the Board subject these firms to "enhanced prudential standards" that are the same as or substantially similar to the new and more stringent standards that the Board will apply to bank holding companies with total consolidated assets of more than $50 billion. The Board recently proposed such standards, and they have been strongly opposed by banking institutions that are potentially subject to them.7 Among other things, the standards could require designated nonbank financial firms to comply with bank holding company regulatory capital requirements, to operate with higher levels of capital and to maintain higher levels of liquidity. Although a nonbank financial firm should have the ability to establish an intermediate holding company that would be subject to the proposed requirements instead, the requirements for such a company are unclear. If the capital standards in the proposed rule apply to the entire firm, the impact of these requirements should not be underestimated. Firms also would be subject to greater oversight and additional limits if their capital were to dip below certain levels or other weaknesses became apparent.

Accordingly, any firm that may be swept into Stage 2 should begin to analyze how it may be reviewed by the Council and what material would be pertinent to that review. The Guidance indicates that the Council will evaluate a firm from the perspective of whether distress at a nonbank financial firm might cause others to become distressed and whether distress at these other companies might cause distress at still other otherwise healthy nonbank financial firms. The central question then is whether either development could contribute to a credit exposure crisis, a liquidity crisis, or the loss of critical products or services that are not readily available. We discuss approaches to these factors below, as well as ways to analyze how those factors might contribute to any of the three crises that the Council has identified. The specific components of each of the factors are described in Annex 1.8

Anticipating how the Council actually will analyze each nonbank financial firm is complex because of the web of factors and potential sources of disruption, as well as the lack of precedents. At the same time, these uncertainties suggest that there may be room to educate the Council on why designation of particular firms is inappropriate, including why other approaches to any risks that the firm may present would be more effective. Indeed, a firm may wish to consider proposing other prudential standards.

Three general points are worth keeping in mind as a firm approaches the analysis of systemic risk. First, while each of these factors should be analyzed with care, communications with the Council should address a broader theme. The designation process ultimately is intended to protect against a future financial crisis. A firm therefore should explain how it fared during the crisis and how it was able to avoid material financial distress. Certain financial firms, among them mutual funds and other asset managers and life insurance companies, have long histories of financial stability in volatile markets, and should make that point to the Council.

Second, some of the Council's concerns have been addressed in the enhanced prudential standards that the Board recently proposed. Since the purpose of the enhanced prudential standards is to reduce systemic risk, a firm that meets these standards should not pose risk with respect to the factor that such standards address. For example, a firm that would comply with the counterparty credit risk exposure limits in the proposed standards should present little or no risk that distress at the firm would create systemically important exposures for those counterparties. Additionally, while the proposed standards call for institution-specific liquidity requirements (rather than stating quantitative standards across the board), a firm that would meet the liquidity requirements that currently are part of Basel III should not present material risk of a liquidity event that would force asset sales that would disrupt the market.9

Third, a nonbank financial firm that has been designated as systemically important must prepare and submit two related plans: a capital plan (or recovery plan) to the Board and a plan for its orderly liquidation in the event of failure to the Board and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. A firm should consider whether it could develop plans of this nature before a designation in order to demonstrate the ease of a recapitalization and an orderly liquidation and the corresponding absence of systemic risk.

Material financial distress

The designation of a nonbank financial firm as systemically important is a complex process. The Council must make two determinations: whether material financial distress, or a combination of factors at the firm, could pose a threat to the financial stability of the United States. Such a threat likely would come through one (or more) of three channels, which are evaluated on the basis of six categories of factors.

The Council will measure the potential effects of financial distress primarily by three factors— size, interconnectedness, and substitutability. In addition to undertaking the appropriate measurements of these factors, we suggest that a firm discuss the precondition to the Council's material financial distress—the likelihood that distress would occur.

Size. The possibility that material financial distress would disrupt the financial markets will be measured initially by size. Total consolidated assets do not necessarily correlate with any of the threats of disruptive credit risk to counterparties, disruption of markets due to liquidation of assets or loss of critical functions. A firm should explain the elements and diversity of its balance sheet, the distinct risks to counterparties, potential effects of the liquidation of assets, and the availability of substitutes for the services that the firm provides. The firm's balance sheet relative to that of its competitors and counterparties should be described as well.

Interconnectedness. The analysis of size should overlap with that of interconnectedness, that is, significant concentrated liabilities are most likely to present concerns about interconnectedness. A firm should be prepared to identify the third parties that have substantial exposure to it. A rule of thumb should be that a firm presents possible systemic exposure risk to a third party where that party's exposure to the firm exceeds 25 percent of that party's capital.10 This standard is the converse of the rule in section 165(e) and the Board's enhanced prudential standards that a nonbank financial firm's exposure to another party should not exceed 25% of the firm's total capital. Exposures below that level should present limited systemic concerns.

Substitutability. This factor presents interesting issues because it should be the principal if not the sole determinant of the "crucial products and services" decision that the Council must make.11 Regarding experience, in the history of bank regulation, substitutability is an antitrust concept that the federal banking agencies have applied in the competition analyses that are a necessary part of the review of merger and acquisition applications. Specifically, substitutability is considered where a market must be defined in order to calculate market share. This analysis does not create a solid precedent for a systemic risk assessment, because the possibility of reduced competition is different from a potential risk to financial stability. Moreover, the banking agencies' analysis of substitutability has been somewhat crude—the markets that have been defined using substitutability have been those for deposits and commercial loans. The products and services offered by large financial institutions are more complex and determining substitutes may be a difficult process.

As a result, a firm should be prepared to educate the Council about substitutability and the importance of distinguishing substitutability as a systemic issue for its more traditional place in competition assessments. In particular, a firm should explain how nominally different products serve similar economic functions and are ready substitutes for one another in the credit and capital markets, as well as how any barriers to entry into the market can be overcome.

Vulnerability to financial distress

Vulnerability to financial distress is a function of three factors, which are somewhat more limited in scope than those that relate to material financial distress: leverage, liquidity risk and maturity mismatch, and the degree of regulatory scrutiny. In addressing the quantitative elements of these factors, a firm should demonstrate how its measurements compare to industry standards and those of its peers to the extent such information is available. In addition, this area in particular should be influenced by how a firm's business model faired in past financial crises.

Leverage. The potential risks inherent in leverage is that lower levels of equity may hasten undercapitalization in a time of stress and generally will make it more difficult for a nonbank financial firm to find necessary financing when financial markets are disrupted. However, leverage involves more than just levels of equity. Short-term liabilities are more likely to trigger assets sales that will, in turn, put pressure on capital than will longer term liabilities. The character of the holders of the liabilities and their potential for flight will also be important. Holders of insurance policies may be much less susceptible to panics that create liquidity pressures than risk-averse holders of unsecured demand obligations. Since different forms of debt and the cost of funds will have different effects on counterparties and future access to liquidity, communications with the Council should analyze a firm's debt structure. A firm should also, of course, explain how it plans to obtain liquidity when under stress and, if applicable, how it has done so in the past. Generally, access to liquidity through assets sales is probably the least favorable approach under the Council's analysis.

Arguably, a protected anchorage, if not a complete safe harbor exists: a ratio of total liabilities to total equity of 15:1. (The bank capital rules present the leverage ratio in converse form, here 6.67 percent.) This ratio is a ceiling imposed by section 165(j) of the Act and the Board's proposed enhanced prudential standards on those nonbank financial firms and bank holding companies with assets greater than $50 billion that present a "grave threat" to U.S. financial stability.

Liquidity risk and maturity mismatch. Liquidity risk for the Council's purpose is the degree to which a nonbank financial firm relies on short-term funding and the firm's ability to find replacement funding. The issue is whether the firm maintains a sufficient amount of readily liquid assets to cover any liabilities over 30-day and one-year time horizons. As noted above, liquidity risk is closely related to, if not a component of leverage. Any submission should identify with precision the nature of any reliance on short-term funding—i.e., which business lines do and do not rely on short-term funding—the diversity of its funding sources and the response of the firm if its different lines are affected by the loss in such funding.

Maturity mismatch relates to the differences in the maturities of a nonbank financial firm's assets and of its liabilities. A firm should be prepared not only to identify the different maturities but also to show any links between particular assets and particular liabilities, which would show the real impact of maturity mismatches. In this regard, the liquidity of assets and the volatility of the markets for these assets will be important components in analyzing their maturity. In addition, interest rate risk is a function partly of maturity mismatches and should be part of the firm's analysis.

Regulatory oversight. Much of the information on the quality of regulatory oversight should already be available to the Council through its member agencies. For example, the insurance regulators' representative can speak to state insurance regulation. The Board has significant relationships with foreign regulators, a number of whom regulate nonbank financial companies as well as banking institutions. The Board already has determined that several foreign regulators provide comprehensive consolidated supervision in the banking sector, and these determinations may inform the Council's analysis. Nevertheless, communication, and more significantly, understanding between and among regulators is notoriously incomplete. In any case, the Council is unlikely to have a full understanding of the specific experience of a firm with its regulators, and a firm should be prepared to provide that information.

Footnotes

1 Financial Stability Oversight Council, Authority to Require Supervision and Regulation of Certain Nonbank Financial Companies 77 Fed. Reg. 21637 (Apr. 11, 2012).

2 The Council may designate as systemically important only those firms "predominantly engaged in financial activities." The Board is responsible for defining "predominantly" and determining the precise meaning of "financial activities" and is now developing a rule. A final rule on this issue is, in our view, a pre-condition to any final designation by the Council, and we discuss it further below.

3 As of the date of this paper, the final rule had not been officially published. It may be accessed at http://www.cftc.gov/ucm/groups/public/@newsroom/documents/file/federalregister041812b.pdf.

4 See 12 C.F.R. § 1310.20(b)(4). However, as noted above, not all firms may be aware that they are in Stage 2.

5 77 Fed. Reg. 21494 (Apr. 10, 2012). This notice is a supplement to an earlier proposal that remains pending, 76 Fed. Reg. 7731 (Feb. 11, 2011). The two releases should be read together.

6 Finalization of the proposed rule and completion of other rulemakings "are not essential to the Council's consideration of whether a nonbank financial company could pose a threat to U.S. financial stability, and the Council has the statutory authority to proceed with determinations under section 113 of the Dodd-Frank Act prior to the adoption of such rules." 77 Fed. Reg. 21637, 21639 (Apr. 11, 2012).

7 77 Fed. Reg. 594 (Jan. 5, 2012).

8 While section 113 and the interpretive guidance (in its description of the Second Determination) raise the possibility that a firm will be designated solely on the basis of its complexity, apparently in the absence of financial distress, the substance of the interpretive guidance deals with scenarios of distress. Given the discussion in the guidance, we would hope that the Council would understand that complexity in the absence of distress is not a meaningful indicator of systemic importance and will not devote inordinate attention to the issue. A firm's activities alone could be problematic only if the firm is so large that a business decision that will not materially affect its financial position could have a ripple effect on smaller counterparties. A healthy firm also might decide to terminate a line of business that would affect smaller participants. In either case, the harm necessarily would be limited to smaller counterparties, and the ripple effect would not be systemically important.

9 Basel III includes two liquidity requirements, a liquidity coverage ratio that addresses liquidity over the next 30 days and a net stable funding ratio that measures liquidity over the coming twelve months. See Basel Comm. On Bkg. Supervision, Basel III: International framework for liquidity risk measurement, standards and monitoring (Dec. 2010), accessible at http://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs188.pdf. The Basel Committee, however, is still reviewing both ratios.

10 For firms with $500 billion or more in worldwide consolidated assets, the rule of thumb should be 10 percent of capital for exposures to any other firms with $500 billion or more in worldwide consolidated assets.

11 The services most likely to present substitutability concerns are those where there is a high concentration— exchanges and clearinghouses. Title VIII of the Act addresses the potential systemic risk of the providers of these services—"financial market utilities"—and the Council already has addressed the potential systemic risk of these services in a final rule. 76 Fed. Reg. 44763 (July 27, 2011).

Annex 1 – The Final Rule

Statutory Requirements

Section 113 of Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act ("Dodd-Frank" or the "Act")1 authorizes the Financial Stability Oversight Council (the "Council") to determine that a nonbank financial institution be supervised by the Board and be subject to enhanced prudential standards if the Council determines that either (i) material financial distress at the company, or (ii) the nature, scope, size, scale, concentration, interconnectedness, or mix of its activities, "could pose a threat to the financial stability of the United States." Such a determination requires a two-thirds vote by the voting members of the Council. The provision identifies ten factors for the Council to consider when reviewing a U.S. nonbank financial company: i. The extent of the leverage of the company;

ii. The extent and nature of its off-balance-sheet exposures;

iii. The extent and nature of its transactions and relationships with other significant nonbank financial companies and significant bank holding companies;

iv. The company's importance as a source of credit for households, businesses, and state and local governments, and as a source of liquidity for the U.S. financial system;

v. The company's importance as a source of credit for low-income, minority, or underserved communities, and the impact that the failure of the company would have on the availability of credit in such communities;

vi. The extent to which assets are managed rather than owned, and the extent to which the ownership of such assets is diffuse;

vii. The nature, scope, size, scale, concentration, interconnectedness, and mix of the activities of the company;

viii. The degree to which the company is already regulated by 1 or more primary financial regulatory agencies;

ix. The amount and nature of the company's financial assets; and

x. The amount and types of the company's liabilities, including the degree to which it relies on short-term funding.

The factors are nearly the same for foreign nonbank financial firms. The one difference is that the eighth factor is replaced by consideration of the nature of the home-country supervision of a firm. The Council is required, as part of the determination process, to consult with the firm's primary financial regulator and any foreign regulatory authorities as appropriate.

Section 113 also outlines the procedures for the Council to follow in making a determination. The Council must provide a company with advance notice that the Council plans to designate the firm as systemically important. The firm may request a hearing within 30 days. If it does so, the Council must schedule a hearing within 30 days, and the firm may submit additional information within those 30 days. The Council must render a final determination within 60 days after hearing. If the firm does not request a hearing, the Council must notify the firm of its final determination within 40 days of the firm's receipt of the advance notice.2 The Council may waive any of the procedural requirements if necessary or appropriate to prevent or mitigate threats to financial stability. The Council must review the determination of each nonbanking firm annually.

Judicial review of a final determination is available, whether or not a hearing has been held. A firm has 30 days in which to file suit in U.S. District Court for either the district in which the firm's headquarters are located or the District of Columbia. The court's standard of review is whether the Council's determination was "arbitrary and capricious."

The Rule

The Rule is the result of a lengthy process. In October 2010, the Council published an advance notice of proposed rulemaking that posed several questions about the nature of systemic importance.3 In January 2011, the Council proposed a set of criteria that reflected the section 113 factors without significant further detail.4 Following comments that complained about the lack of guidance in the January proposal, the Council released a second proposal in October 2011, with a formal rule and interpretive guidance.5 The Rule adopts substantially all of the second proposal. The formal regulation itself is procedural in nature. The substantive discussion of the Council's analysis of systemic importance lies in the interpretive guidance, with some gloss provided in the Council's explanation of the Rule in the supplementary information.

Analytic Framework

The designation of a nonbank financial firm as systemically important is a complex process. The Council must make two determinations, whether material financial distress (the "First Determination Standard") or a combination of factors at the firm (the "Second Determination Standard") could pose a threat to the financial stability of the United States. Such a threat likely would come through one (or more) of three channels, which are evaluated on the basis of six categories of factors.

Determination Standards

The ultimate decision of a threat to financial stability will be based on either or both of two different standards, depending on which set of facts exists. The Council recognizes that in many cases both determinations will be justified.

To view this article in full together with its footnotes please click here.

Because of the generality of this update, the information provided herein may not be applicable in all situations and should not be acted upon without specific legal advice based on particular situations.

© Morrison & Foerster LLP. All rights reserved