Previously published in The John Liner Review (Winter 2011)

Something has gone wrong — something unforeseen, unfortunate, and expensive. An insurance company's refusal to pay a claim can be devastating. Now you have a two-front war: You must contend with the cost and consequence of your loss and deal with your insurance company's refusal to pay.

Some jurisdictions will force the insurance company to pay your legal fees regarding the coverage dispute. These courts have recognized that without this potential consequence, insurance companies have an incentive to breach their duties under the insurance policy.1 By using this "opportunistic breach," an insurance company may deny coverage wrongfully, continue to collect and invest premiums during its well-financed coverage litigation, and the only penalty it risks is paying the policyholder the same coverage it owed all along. As the Colorado Supreme Court stated:

Contract damages offer no motivation whatsoever for the insurer not to breach. If the only damages an insurer will have to pay upon a judgment of breach are the amounts that it would have owed under the policy plus interest, it has every interest in retaining the money, earning the higher rates of interest on the outside market, and hoping eventually to force the insured into a settlement for less than the policy amount.2

That is why policyholders and insurance companies alike should be aware that a majority of states permit the recovery of attorney fees by a prevailing policyholder in a coverage dispute. Such a rule increases the risk associated with an adverse outcome for the insurance company and should be used by policyholders to help, at least in part, level the playing field.

Courts and legislatures have come to this unusual conclusion because there is an understanding that insurance is different.3 Courts have frequently noted that the "disparity of bargaining power between an insurance company and its policyholder makes the insurance contract substantially different from other commercial contracts."4 Moreover, when buying insurance, policyholders intend to purchase peace of mind, not litigation, with their insurance company when a claim is made.

Policyholders may also be permitted to recover fees for in-house counsel as costs of pursuing insurance coverage. The cost of using the policyholder's in-house legal staff should be recoverable just as outside counsel fees may be recovered in a successful insurance coverage case. Some courts considering this issue have permitted policyholders to recover corporate counsel costs incurred both in the underlying action and the insurance coverage action.

Even after the insurance company has sought to avoid its duty to defend under the policy, it nevertheless may contest the amount of fees the policyholder expended in its own defense. After the insurance company is found to have wrongfully denied its duty to defend, any attorney fees the policyholder has paid without knowing whether it will be reimbursed should be held reasonable as a matter of law.

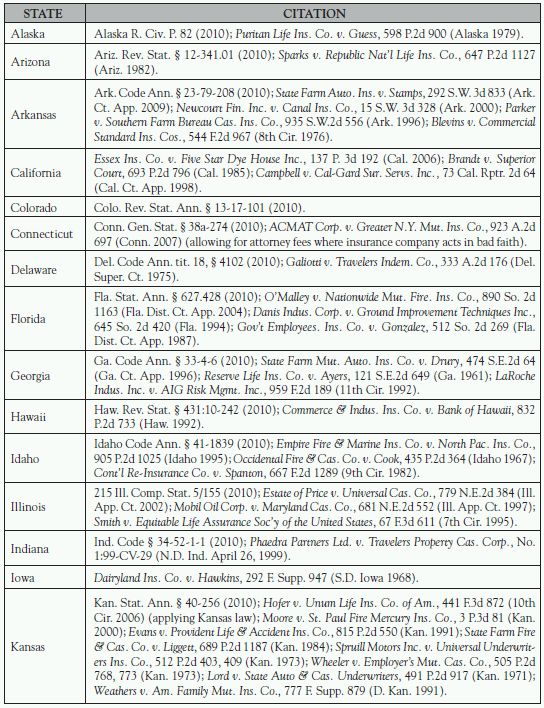

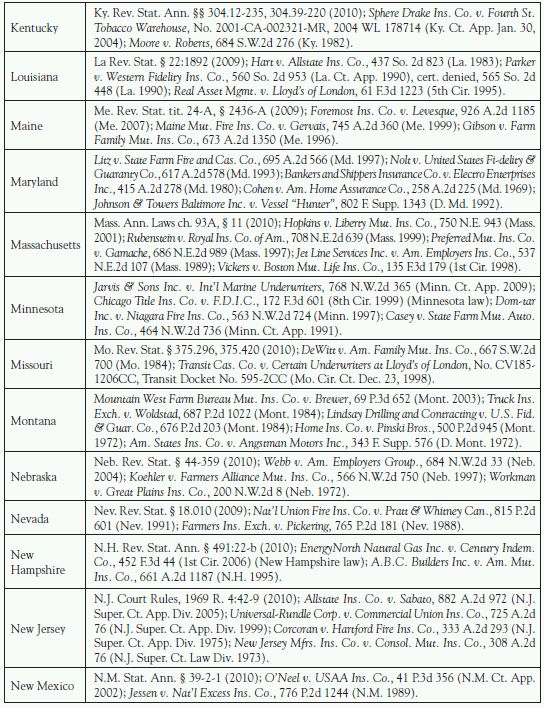

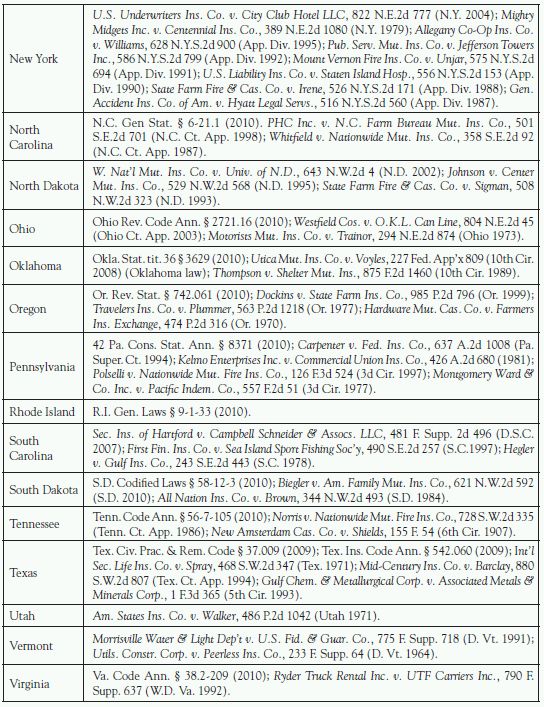

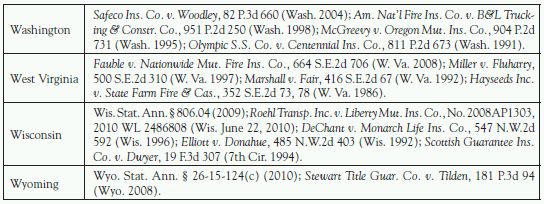

This article discusses the approaches of a number of states in awarding policyholders their attorney fees in coverage disputes, as supported by statutes, common law, and commentators.5 The second part discusses the potential for recovering in-house counsel costs. The third part discusses the reasonableness of the policyholder's defense fees when the insurance company has breached its duty to defend and then seeks to avoid reimbursement. Finally, a state-by-state survey of authority potentially helpful to policyholders seeking to recover attorney fees in insurance coverage actions is included in the Appendix to this article.6

Recovery of Policyholder Attorney Fees

There are a number of rationales for an award of attorney fees to policyholders in insurance coverage disputes. These rationales generally are founded on (1) the nature of the insurance promise; for example, the nature of an insurance company's duty to defend its policyholder; (2) the theory of consequential damages; (3) the language of particular insurance policy provisions; (4) public policy considerations; and (5) specific statutory provisions.

Rationales Supporting the Award of Policyholder Attorney Fees

An insurance company's improper refusal to defend the policyholder should entitle the policyholder to recover attorney fees and costs. Although the vast majority of jurisdictions permit attorney fees in coverage actions to some degree, courts in several jurisdictions have limited the scope and applicability of attorney fee awards. This is particularly true in the context of third-party liability insurance. Where the policyholder establishes the insurance company's duty to defend in a subsequent declaratory judgment action, the insurance company should bear the consequences of its wrongful action and reimburse the policyholder for its attorney fees and costs in the declaratory judgment action. For example, in Legacy Partners Inc. v. Travelers Ins. Co., the court found that under Texas law "an insurer who has breached the duty to defend is liable for damages including the attorneys' fees incurred in pursuing an insurance coverage action."7

In the liability insurance context, a breach of the duty to defend is one event supporting an award of policyholder attorney fees. The nature of the insurance promise as "peace of mind" and "liability insurance" is such that the award of attorney fees to a policyholder in a coverage action protects the value of the "duty to defend" provision.

Courts have described an insurance company's duty to provide a timely defense as "litigation insurance." In City of Johnstown v. Bankers Standard Insurance Co., the Second Circuit Court of Appeals stated: "The insurer's duty to defend works, in essence, as a form of 'litigation insurance' for the insured."8 Additionally, in Rubenstein v. Royal Insurance Co. of America, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court noted that "the promise to defend the insured, as well as the promise to indemnify, is the consideration received by the insured for payment of the policy premiums. Although the type of policy here considered is most often referred to as liability insurance, it is 'litigation insurance' as well, protecting the insured from the expense of defending suits brought against him."9 Litigation insurance that functions only after the underlying litigation is complete is a sham.

In Montrose Chemical Corp. v. American Motorists Insurance Co., the court upheld an order requiring immediate payment of the policyholder's defense costs in the underlying action and reimbursement for past defense costs with interest. The court ruled that the insurance company must undertake the duty to defend obligation promptly:

By requiring the prompt resolution of a carrier's duty to defend prior to the resolution of the underlying liability actions, the courts protect the insured's right to peace of mind and security, a right which would ring resoundingly hollow were the holder compelled to simultaneously enforce rights under the policy and defend a costly and potentially devastating claim.10

An insurance company is required to assume defense costs in a timely manner so that "policyholders thus are assured that they need not expend their own funds in order to receive protection for liability."11 Courts have emphasized the unique importance of the time element of the duty to defend in awarding specific performance of this obligation and rejecting the claim that a later damage award is sufficient to adequately compensate a breach. In Avondale Industries Inc. v. Travelers Indemnity Co., the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York granted the policyholder's motion for entry of final judgment, rejecting the insurance company's argument that the policyholder possessed the financial resources to permit the policyholder to continue to wait for coverage:

[T]his Court does not see any reason why [the policyholder] should have to wait until some indefinite future date to receive the defense to which it is entitled ... To suggest that the passage of time matters not to the plaintiffs in such circumstances, and that enforcement of the duty to defend can await another day, denigrates the professional obligation here found to have been undertaken.12

In McGinniss v. Employers Reinsurance Corp., the court ruled: "Without contemporaneous payment of defense costs, the insurance would not truly protect the insureds from financial harm caused by suits against them."13

For the defense obligation to be effective, costs must be paid "as they were and are incurred," per the court in Village Management Inc. v. Hartford Accident & Indemnity Co. When ordering immediate payment of defense costs, the court in Village Management rejected the suggestion that an insurance company could delay payment until the conclusion of coverage disputes, commenting, "[T]hat notion is hard to reconcile with the concept that the duty to defend is not at all coextensive with policy coverage."14

Some courts have adopted the rationale that the insurance company has authorized by implication the expenditure of attorney fees by the insured as a result of the insurance company's failure to defend. In Occidental Fire & Casualty Co. v. Cook, the Idaho Supreme Court ruled that the award of "reasonable expenses," as promised in the policy, includes attorney fees expended in declaratory judgment action because the effect on the policyholder is as burdensome as any other type of legal action.15

Rationales for awarding attorney fees to policyholders from insurance companies sometimes have a broad reach beyond the context of third-party liability insurance policies. Some jurisdictions, quite properly, have awarded attorney fees as consequential damages for breach of contract in the declaratory judgment action. A number of cases support this action. In Hayseeds Inc. v. State Farm Fire & Casualty, the West Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals stated: "[W]e hold today that when a policyholder substantially prevails in a property damage suit against an insurer, the policyholder is entitled to damages for net economic loss caused by the delay in settlement, as well as an award for aggravation and inconvenience."16 In Federated Mutual Insurance Co. v. Grapevine Excavation Inc., the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals stated, "[I]n a policyholder's successful suit for breach of contract against an insurer that is subject to the provisions listed in section 38.006, the insurer is liable for reasonable attorney's fees incurred in pursuing the breach-of-contract action under Section 38.001 unless the insurer is liable for attorney's fees under another statutory scheme."17

In addition, even New York courts, which previously have allowed recovery of attorney fees only when the policyholder is on the defensive, have recognized that the fees may be recoverable as consequential damages when the policyholder brings a breach-of-contract action against the insurance company.18

Other courts have found that attorney fees constitute an element of the policyholder's damages for the insurance company's bad-faith refusal to pay a claim. For example, in Taylor v. State Farm Fire and Casualty Co., the Supreme Court of Oklahoma held that:

when an action is pressed for bad-faith refusal to settle ... the plaintiff may seek damages (a) for the loss payable under the policy together with (b) those other items of recovery that are consistent with harm flowing from insurer's bad-faith breach of its implied-in-law duty to settle.19

Courts in a number of jurisdictions can look to statutory law in order to justify an award of attorney fees. The legislatures in a majority of states have passed laws that provide for attorney fees. Some statutes are drafted broadly, such in New Hampshire, where the law states:

In any action to determine coverage of an insurance policy pursuant to RSA 491:22, if the insured prevails in such action, he shall receive court costs and reasonable attorneys' fees from the insurer.20

Other statutes are drafted differently, such as in Virginia, where recovery is permitted in cases where an insurance company not acting in good faith failed to make payment to the policyholder.21 Likewise, in Louisiana, a policyholder will be entitled to attorney fees if his insurance company has acted in bad faith, for example, by "[m]isrepresenting pertinent facts or insurance policy provisions relating to any coverages at issue."22 Some states permit policyholders to obtain attorney fees under general statutes, such as in Arizona, where the law potentially provides for attorney fees in all contract actions.23 Even states that typically do not permit attorney fees allow policyholders to recover attorney fees in specific circumstances. For example, in Delaware the law provides for reasonable attorney fees for "property insurance" coverage actions.24

Finally, some jurisdictions have held that where a statute is drafted narrowly, a policyholder will not be denied attorney fees due to a rigid interpretation of the language of said statute. For example, Oklahoma law provides, in relevant part, that "[i]t shall be the duty of the insurer, receiving a proof of loss, to submit a written offer of settlement or rejection of the claim to the insured party within ninety (90) days of receipt of that proof of loss. Upon a judgment rendered to either party, costs and attorney fees shall be allowable to the prevailing party."25 In Stauth v. National Union Fire Insurance. Co., the insurance company tried to argue that its policyholder, who had prevailed in a coverage action, was not entitled to attorney fees because he had not submitted a formal proof of loss. The Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals held, however, that the terms of the policy at issue required only that the policyholder provide written notice of loss and not a conventional proof of loss statement. Thus, the policyholder satisfied the "proof of loss" requirement when he notified his insurance company of his loss.26

A number of courts have awarded attorney fees in cases where the insurer engages in bad faith, fraud, stubborn litigiousness, or vexatious conduct. In Mobil Oil Corp. v. Maryland Casualty Co., attorney fees were authorized on showing of vexatious and unreasonable conduct by the insurance company in refusing the claim.27 In Brandt v. Superior Court, the Supreme Court of California ruled that attorney fees are recoverable where the insurance company tortiously withholds benefits.28 This approach, however, has been particularly criticized in the context of liability insurance policies. In Hayseeds, the Supreme Court of Appeals of West Virginia stated:

[W]e consider it of little importance whether an insurer contests an insured's claim in good or bad faith. In either case, the insured is out his consequential damages and attorney's fees. To impose upon the insured the cost of compelling his insurer to honor its contractual obligation is effectively to deny him the benefit of his bargain.29

Likewise, Appleman criticizes the approach of courts that refuse to award attorney fees in declaratory judgment actions absent bad conduct on the part of the insurance company as fundamentally unfair to the policyholder:

After all, the insurer had contracted to defend the insured, and it failed to do so. It guessed wrong as to its duty, and should be compelled to bear the consequences thereof. If the rule laid down by these courts should be followed by other authorities, it would actually amount to permitting the insurer to do by indirection that which it could not do directly. That is, the insured has a contract right to have actions against him defended by the insurer, at its expense. If the insurer can force him into a declaratory judgment proceeding and, even though it loses in such action, compel him to bear the expense of such litigation, the insured is actually no better off financially than if he had never had the contract right mentioned above. Other courts have refused to impose such a burden upon the insured.30

An increasing number of jurisdictions are allowing recovery of attorney fees in insurance coverage actions. Policyholders and their counsel should always consider the possibility of recovering attorney fees. Furthermore, the bedrock reasons underlying many of these decisions support an argument for the expansion of attorney fees in jurisdictions that inappropriately prohibit or limit attorney fees in insurance coverage actions.

Selected Review of Recovery of Policyholder Attorney Fees

Set forth below is a review of the law of Maryland, Kansas, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, and Washington. As noted above, a state-by-state chart appears in the Appendix. Also below is an insurance company's own argument that supports an award of policyholder attorney fees.

Maryland Permits Recovery of Policyholder Attorney Fees

Maryland courts have stated unwaveringly that "[t]he rule in this State is firmly established that when an insured must resort to litigation to enforce its liability insurer's contractual duty to provide coverage for its potential liability to injured third persons, the insured is entitled to a recovery of the attorneys' fees and expenses incurred in that litigation."31

Indeed, under Maryland law, policyholders are entitled to recover attorney fees incurred in seeking coverage from an insurance company that has wrongfully breached its duty to defend under a third-party liability policy. In Cohen v. American Home Assurance Co., the Court of Appeals of Maryland awarded attorney fees to the prevailing policyholder, stating:

American Home produced the current situation when it refused to defend its assured. Accordingly, whether one speaks in terms of its having authorized the expenditure by its failure to defend or whether one speaks in terms of the attorney's fees for the declaratory judgment action being a part of the damages sustained by the insured by American Home's wrongful breach of the contract, we hold American Home bound to pay the fees incurred by [the policyholder] in bringing the declaratory judgment action to establish that American Home had not done that which it had agreed with her to do.32

Similarly, in Bankers and Shippers Insurance Co. of New York v. Electro Enterprises Inc., the Court of Appeals of Maryland again awarded the policyholder its attorney fees in its coverage dispute with the insurance company, stating:

[A]n insurer is liable for the damages, including attorneys' fees incurred by an insured as a result of the insurer's breach of its contractual obligation to defend the insured against a claim potentially within the policy's coverage, and this is so whether the attorneys' fees are incurred in defending against the underlying damage claim or in a declaratory judgment action to determine coverage and a duty to defend.33

Moreover, the Bankers and Shippers court continued:

Furthermore, the right of an insured to recover attorneys' fees in such a situation applies not only to the named insured of the policy but also to any person who is within the policy definition of an insured and against whom a claim alleging a loss within the policy coverage has been filed.34

Kansas Permits Recovery of Policyholder Attorney Fees

Under Kansas law, a policyholder is entitled to its reasonable attorney fees when it is forced to sue an insurance company for refusing "without just cause or excuse" to defend or indemnify the policyholder. Specifically, K.S.A., section 40-256, provides:

That in all actions hereafter commenced, in which judgment is rendered against any insurer as defined in K.S.A. 40 201... on any policy or certificate of any type or kind of insurance, if it appears from the evidence that such company ... has refused without just cause or excuse to pay the full amount of such loss, the court in rendering such judgment shall allow the plaintiff a reasonable sum as an attorney's fee for services in such action, including proceedings upon appeal, to be recovered and collected as a part of the costs ....

The Kansas Supreme Court has held that the determination of whether the insurance company's actions were "without just cause or excuse" depends on the facts and the circumstances of each case.

In Wheeler v. Employer's Mutual Casualty Co., the Kansas Supreme Court rejected the insurance company's argument that it properly denied coverage under an automobile policy on grounds that the named insured was not occupying an automobile at the time of the accident. The court held that even though the interpretation of the policy provision in question presented an issue of first impression, this did not justify the insurance company's denial of the claim. Where the great weight of authority is contrary to the insurance company's position, the court held that an award of attorney fees is proper.35

Kansas courts consistently have held that an insurance company's failure to investigate a claim thoroughly before denying coverage is grounds for awarding attorney fees under K.S.A. Section 40-256.36

In Lord v. State Automobile & Casualty Underwriters, the Kansas Supreme Court upheld an award of attorney fees based on the insurance company's failure to investigate a claim brought by a policyholder to recover the value of his truck. In affirming an award of attorney fees under K.S.A. Section 40-256, the Kansas Supreme Court held that the insurance company acted "without just cause or excuse" in refusing the claim because the insurance company did not conduct a thorough investigation of the policyholder's claim:

[W]e recognize that the company has a duty to make a good faith investigation of the facts before finally refusing to pay .... [T]he insurance company put the entire burden on its insured, taking the somewhat lofty position that investigation, evaluation, and determination of the claim was not its responsibility. That the [claim] might be based on erroneous facts, or be a "nuisance" claim, or be wholly frivolous was none of its concern; it would not deign even to inquire. In short, it did not know and did not care whether its "cause or excuse" for refusing to pay was "just."37

Moreover, the Kansas Supreme Court has held that K.S.A. § 40-256 entitles a prevailing policyholder who already has recovered attorney fees from the coverage dispute to also seek subsequent attorney fees incurred defending the reasonableness of the coverage dispute fees. In Moore v. St. Paul Fire Mercury Insurance Co., in awarding the fees, the court reasoned:

The primary purpose of the Kansas fee-shifting statute is to benefit the insured. Fees incurred litigating the amount of attorney fees to be awarded are recoverable under K.S.A. 40-256. The fact that the award of such fee ultimately results in the insured's attorney being paid to litigate the fee is collateral and incidental to the primary purpose of indemnifying an insured for the cost of counsel in an action against the insurer.38

New Jersey Permits Recovery of Policyholder Attorney Fees

The New Jersey Rules of Court explicitly provide for the recovery by the policyholder of the attorney fees and costs incurred in successfully enforcing its rights under an insurance policy. New Jersey Rule 4:42-9 provides:

(a) Actions in Which Fee Is Allowable. No fee for legal services shall be allowed in the taxed costs or otherwise, except ... (6) In an action upon a liability or indemnity policy of insurance, in favor of a successful claimant.

A successful policyholder may recover its attorney fees under New Jersey law even if the insurance company's refusal to honor its obligations under its policy was made in good faith.39

New York Permits Recovery of Policyholder Attorney Fees

In Mighty Midgets Inc. v. Centennial Insurance Co., the New York Court of Appeals held that in an insurance coverage action, a policyholder is entitled to recover its litigation expenses "when [the policyholder] has been cast in a defensive posture by the legal steps an insurer takes in an effort to free itself from its policy obligations."40 New York courts have not hesitated to award policyholders attorney fees and costs for having successfully defended actions against insurance companies seeking to walk away from their duties under their insurance policies. In GRE Insurance Group v. GMA Accessories Inc., the court held that "[s]ince plaintiff brought this declaratory judgment action seeking to free itself from its policy obligations, defendant is therefore also entitled to recover its reasonable costs and attorney fees incurred in successfully defending this action thus far."41 Furthermore, recovery of attorney fees by a policyholder that has been sued by its insurance company does not depend on a breach of a duty to defend. In U.S. Underwriters Insurance Co. v. City Club Hotel LLC, the insurance company disclaimed coverage under an employee exclusion in the policy and brought a declaratory judgment action, but nevertheless defended the policyholder in the underlying action. The policyholder prevailed in the coverage action and sought its attorney fees even though the insurance company had not breached the policy.

The New York Court of Appeals, on certification from the Second Circuit, reaffirmed the Mighty Midgets rule and held that:

an insured who prevails in an action brought by an insurance company seeking a declaratory judgment that it has no duty to defend or indemnify the insured may recover attorneys' fees regardless of whether the insurer provided a defense to the insured.42

Indeed, New York courts have been resolute in awarding attorney fees in coverage actions, because "an insurer's duty to defend an insured extends to the defense of any action arising out of the occurrence, including a defense against an insurer's declaratory judgment action."43

Ohio Permits Recovery of Policyholder Attorney Fees

Under Ohio law, a policyholder may recover the costs it has incurred in a successful declaratory judgment action to force an insurance company to honor its policy obligations. In the case of insurance coverage declaratory judgment actions, the Ohio Supreme Court has carved out an exception to the general rule that costs and attorney fees are usually not recoverable in breach of contract actions. The reason for this, according to Motorists Mutual Insurance Co. v. Trainor, is that the policyholder "must be put in a position as good as that which he would have occupied if the insurer had performed its duty."44

Washington Permits Recovery of Policyholder Attorney Fees

In Washington, it is well established that courts may award attorney fees to a prevailing policyholder. According to the Washington Supreme Court in Olympic Steamship Co. v. Centennial Insurance Co.:

We also extend the right of an insured to recoup attorney fees that it incurs because an insurer refuses to defend or pay the justified action or claim of the insured, regardless of whether a lawsuit is filed against the insured. Other courts have recognized that disparity of bargaining power between an insurance company and its policyholder makes the insurance contract substantially different from other commercial contracts. When an insured purchases a contract of insurance, it seeks protection from expenses arising from litigation, not vexatious, time-consuming, expensive litigation with his insurer. Whether the insured must defend a suit filed by third parties, appear in a declaratory action, or as in this case, file a suit for damages to obtain the benefit of its insurance contract is irrelevant. In every case, the conduct of the insurer imposes upon the insured the cost of compelling the insurer to honor its commitment and, thus, is equally burdensome to the insured. Further, allowing an award of attorney fees will encourage the prompt payment of claims.45

The purpose of awarding Olympic Steamship attorney fees to a prevailing policyholder is to make the policyholder whole. The court upheld that principle in McGreevy v. Oregon Mutual Insurance Co.:

[W]hen an insurer unsuccessfully contests coverage, it has placed its interests above the insured. Our decision in Olympic Steamship remedies this inequity by requiring that the insured be made whole.46

The rationale underlying the decision in Olympic Steamship, as stated in McGreevy, is the enhanced fiduciary obligation that an insurance company owes its policyholder not to engage in any action or conduct "which would demonstrate a greater concern for the insurer's monetary interest than for the insured's financial risk."47

Insurance Company Argues in Favor of Awarding Attorney Fees

At least one insurance company, Liberty Mutual, has argued in support of the policyholder view. In a brief filed in Liberty Mutual Insurance Co. v. Continental Casualty Co., Liberty Mutual stated:

On the crucial issue of providing a defense, both Superior Court and Supreme Court concluded that Continental was obligated to defend [the policyholder]. To the detriment of [the policyholder], Continental, which had drafted the insurance contract, refused to recognize its duty to defend. As a result of Continental's mistake, [the policyholder] was left in a position where it incurred substantial attorneys' fees for asserting what it was entitled to all along, a defense. Where the sum and substance of an insurance policy is to provide for leaving the insured free of financial losses in those instances where coverage does exist, the attorneys' fees incurred in litigating an action to establish coverage are a proper element of damages where the insurer is the party who has breached the contract ....

A number of jurisdictions, which, like Massachusetts, follow the general rule that attorneys' fees are not recoverable by prevailing party, provide for an exception where attorney fees are incurred by a successful insured in a declaratory judgment action where coverage was denied by the insurer. Hegler v. Gulf Insurance Co., 270 S.C. 548, 243 S.E.2d 443 (1978); Brown v. United States Fidelity & Guaranty, 46 A.D.2d 97, 361 N.Y.S.2d 232 (1974); Landie v. Century Indemnity Co., 390 S.W.2d 558 (Mo. App. 1965); See Utilities Construction Corp. v. Peerless Insurance Co., 233 F. Supp. 64 (D. Vt. 1964); Motorists Mutual Insurance Co. v. Trainor, 33 Ohio St. 2d 41, 294 N.E.2d 874 (1973) (the rationale being, to put the insured in as good a position as that which he would have occupied had the insurer performed its duty); accord, Allstate Insurer v. Robins, 42 Colo. App. 539, 597 P.2d 1052 (1979). Attorneys' fees, such as those incurred by [the policyholder] in the course of litigating the Continental declaratory judgment action, have also been ruled recoverable as a loss resulting directly from the breach of the insurer's promise to defend. Morrison v. Swenson, 274 Minn. 127, 142 N.W.2d 640 (1966), Cohen v. American Home Assurance Co., 255 Md. 334, 258 A.2d 225 (1969). There is nothing extraordinary about permitting recovery of the attorney fees incurred by [the policyholder].48

Insurance companies are fully aware that the vast majority of courts across the nation are awarding attorney fees in connection with an insurance coverage action and will argue for attorney fees where it suits their interests. Policyholders should not allow insurance companies to argue against attorney fees where those same insurance companies wrongfully refuse to pay the policyholder's claim.

Recovery of Corporate Counsel Fees

The cost of using the policyholder's in-house legal staff should be recoverable at least to the same extent that the costs of outside counsel may be recovered in a successful insurance coverage case.49 A number of courts considering the issue have permitted policyholders to recover corporate counsel costs incurred in the underlying action. In Stichman v. Michigan Mutual Liability Co., the court held that the insurance company was liable for expenses reasonably incurred by the policyholder, including time devoted to defense of the underlying action by three attorneys in the policyholder's employ.50 Some courts have extended recovery of corporate counsel fees to the insurance coverage action itself. In Dale Electronics Inc. v. Federal Insurance Co., the Nebraska Supreme Court held that the statute providing for attorney fees in coverage actions "entitled [the policyholder] to the allowance of an attorney's fee even for in-house counsel."51

A landmark case awarding corporate counsel fees to a policyholder is Pittsburgh Plate Glass Co. v. Fidelity and Casualty Co.52 In Pittsburgh Plate, the policyholder, a paint manufacturer, was sued by one of its customers, a company that made Venetian blinds. Evidently, the paint used and purchased from the policyholder flaked off of the Venetian blinds onto customers' hands. The Venetian blinds manufacturer sought to recover the expense of repairing the blinds and other damage caused by the policyholder's product. The policyholder settled the action against it after its insurance company refused to defend it against the Venetian blind manufacturer or indemnify it for the cost of funding the settlement.

In Pittsburgh Plate, the policyholder utilized two of its corporate counsel to defend the underlying action against it after its insurance company refused to honor its defense obligation. In the ensuing insurance coverage case, the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit held that the insurance company wrongfully refused to defend the underlying action and awarded attorney fees to the policyholder. The insurance company did not question the award of outside counsel fees, but did argue that it should not be responsible for the policyholder's corporate counsel fees. In awarding the policyholder's corporate counsel costs, the court ruled that "[t]here is no reason in law or in equity why the insurer should benefit from [the policyholder's] choice to proceed with some of the work through its own legal department."53

Several courts have adopted the reasoning and the doctrine of Pittsburgh Plate in rendering their decisions. For example, in United States v. State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance Co., the United States District Court for the District of Oregon followed the court in Pittsburgh Plate and awarded the policyholder, the United States, attorney fees for work performed by government attorneys.54 The court found that the United States was an "insured" under one of its employee's insurance policies and ruled that government attorneys are analogous to corporate counsel. The United States was able to recover the value of legal costs associated with the defense of two underlying actions and the costs of its insurance coverage suit. The court further held that corporate counsel fees are recoverable to the same extent that outside counsel fees are recoverable. Additionally, in Goldblatt Bros. v. Home Indemnity Co., the court awarded the policyholder attorney fees of in-house counsel,55 and in Bailey v. United States, the court allowed attorney fees to the government-insured despite the fact that the policyholder did not incur out-of-pocket expenses.56

In United States v. Myers, the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit cited the court's decision in State Farm as support for awarding corporate counsel fees.57 The court awarded the policyholder, again the United States, attorney fees for the use of government lawyers in the underlying action that the insurance company refused to defend. The Fifth Circuit disagreed with the insurance company's argument that the use of salaried lawyers precluded recovery for their fees. The court held that "where an insured must conduct its own defense due to an unwarranted refusal to defend by the insurer, the insured is entitled to recover the expenses of litigation, including attorney's fees."58

In Travelers Insurance Co. v. State Insurance Fund, a case awarding corporate counsel fees, Travelers argued in favor of an award of in-house attorney fees.59 Travelers sued another insurance company for contribution for costs incurred by reason of defending the policyholder in an underlying litigation and funding its settlement. Although insurance companies typically argue against the recovery of corporate counsel fees, Travelers was in the interesting position of advocating for the award. The New York Court of Claims held that "where an insurer wrongfully refuses to defend, the insured may recover its defense costs, including those attributable to in-house counsel."60 The court noted that all of the cases that have addressed this issue have concluded that the policyholder, if victorious in its coverage case, is entitled to the costs of utilizing its corporate counsel.

Reasonableness of Attorney Fees

Even when the insurance company forces its policyholder into coverage litigation by denying a duty to defend the underlying litigation, it may nevertheless attempt to appoint its policyholder's defense counsel. However, while it is in the policyholder's best interest to vigorously and efficiently defend the underlying action, the insurance company's interest may be to expend as little time and money as possible.

It is well settled that where a conflict of interest is probable, the policyholder is entitled to choose its own independent defense counsel for the underlying action.61 Courts of New York and other states have consistently held that:

the law is clear that where a conflict of interest is probable [between the insurance company and insured], selection of attorneys to represent the insured should be made by the insured rather than by the insurance company, which should remain liable for reasonable fees.62

The insurance company's obligation to defend its policyholder "extends to paying the reasonable value of the legal services and costs performed by independent counsel selected by the insured."63

However, after the insurance company is found to have breached its duty to defend the policyholder, and thus is obligated to pay the underlying defense costs, the insurance company may nevertheless contest the reasonableness of those fees. In determining whether a fee is reasonable, often courts will look at the entirety of the representation, considering factors such as the nature of the case and the issues presented; the time and labor required; the amount of damages involved; the result obtained; the experience, reputation, and ability of the attorney; and the usual price charged for similar services by other attorneys in the same area.64

However, increasingly, courts have considered the position the policyholder is in when the insurance company refuses to pay for its defense and have held that the fees actually paid by the policyholder in its own defense are reasonable as a matter of law. In Taco Bell Corp. v. Continental Casualty Co., the policyholder was accused of misappropriating the plaintiff's marketing gimmick, and therefore it sought defense costs under the "advertising injury" coverage of its insurance policy with Zurich.65 Zurich refused to pay its policyholder's defense costs, forcing Taco Bell to incur and pay its own attorney fees of $2.8 million, roughly $0.8 million of which Zurich was responsible for, after a $2 million self-insured retention.66

Nevertheless, Zurich argued that its policyholder overpaid for legal services and sought to introduce detailed records and affidavits to prove that assertion. The court logically refuted Zurich's "excessive fees" argument by stating:

When Taco Bell hired its lawyers, and indeed at all times since, Zurich was vigorously denying that it had any duty to defend — any duty, therefore, to reimburse Taco Bell. Because of the resulting uncertainty about reimbursement, Taco Bell had an incentive to minimize its legal expenses (for it might not be able to shift them); and where there are market incentives to economize, there is no occasion for a painstaking judicial review.67

The court iterated that had Zurich truly mistrusted its policyholder's ability to minimize its own legal fees, it could have selected, supervised, and paid for Taco Bell's lawyers, all while reserving its right to deny it had duty to defend, and seek reimbursement later. Instead, Zurich put its policyholder in a position where it had to assume its own defense costs with no assurance of reimbursement.

In such cases, the fact that the policyholder has paid the underlying legal fees without knowing if it will ever be reimbursed is prima facie evidence that the fees are reasonable.68

Therefore, the insurance company can no longer undermine its duty to reimburse fees by hiring an audit firm and obtaining an evidentiary hearing to pick apart a law firm's billing. Instead, courts recognize that the fact that the insurance company forced its policyholder to pay for its own defense with no guarantee of reimbursement is enough to show that the amount in fees is inherently reasonable.

Conclusion

When your insurance company denies a significant claim, be aware that a majority of states have useful precedent that may support an argument to require the insurance company to pay for the insurance coverage fight. The rationales and precise functioning of these rules differ by jurisdiction. Some jurisdictions currently have rules that are not particularly policyholder friendly and other jurisdictions are silent on the issue.

Some courts have ruled that policyholders should be permitted to recover for in-house counsel expenses at least as broadly as outside counsel fees in a successful insurance coverage action. Moreover, an increasing number of courts are finding that when the insurance company wrongfully refuses to defend and then contests the amount of defense costs, the fact that the policyholder has paid its own legal fees in the underlying litigation is prima facie evidence of their reasonableness.69

Footnotes

1 See Anderson, E.R., et al., Insurance Coverage Litigation § 2.00 (2d ed. 2009); E.A Farnsworth, "Legal Remedies for Beach of Contract," 70 Colum. L. Rev. 1145 (Nov. 1970).

2 Cary v. United of Omaha Life Ins. Co., 68 P.3d 462, 468 (Colo. 2003) (citing Dodge v. Fid. & Deposit Co. of Maryland, 778 P.2d 1240, 1242-43 [Ariz. 1989]).

3 See J.M. Draper, "Insured's Right to Recover Attorney Fees Incurred In Declaratory Judgment Action to Determine Existence of Coverage Under Liability Policy," 87 A.L.R. 3d 429 (1978); F.A. Wisner, "Insurer's Liability for Insured's Attorney Fees In Declaratory Judgment Actions," The Brief 28, no. 1 (Fall 1998): 58.

4 Olympic Steamship Co. v. Centennial Ins. Co., 811 P.2d 673, 681 (Wash. 1991).

5 Under what is often called the "American rule," each side is generally responsible for its own attorney fees in civil cases. See Alyeska Pipeline Serv. Co. v. Wilderness Soc'y, 421 U.S. 240, 257 (1975).

6 Courts in some jurisdictions have held in the past that policyholders may not be able to recover attorney fees in coverage disputes. See, e.g., Green v. Standard Fire Ins. Co., 477 So. 2d 333, 335 (Ala. 1985), which held that attorney fees from an insurance coverage declaratory action are not recoverable, but refused to decide whether such a claim is absolutely precluded because the insurance company's claim was not frivolous. Even in these states — and others without precedent on the issue — the arguments set forth in support of a policyholder fee award may be valuable. See, e.g., Greer v. Burkhardt, 58 F.3d 1070, 1075 (5th Cir. 1995), which observed that although Mississippi law permits recovery of attorney fees only where punitive damages have been awarded, "some [Mississippi] cases indicate that attorney's fees can be awarded as extra-contractual or consequential damages even where punitive damages are not warranted, if the insurer denied a claim without any arguable basis."

7 Legacy Partners Inc. v. Travelers Ins. Co., 2002 WL 500771, at *5 (N.D. Cal. Mar. 29, 2002). See also Montgomery Ward & Co. v. Pacific Indem. Co., 557 F.2d 51 (3d Cir. 1977), which upheld the award of attorney fees because of public policy considerations under Pennsylvania law.

8 City of Johnstown v. Bankers Standard Ins. Co., 877 F.2d 1146, 1148 (2d Cir. 1989).

9 Rubenstein v. Royal Ins. Co. of America, 708 N.E.2d 639, 642 (Mass. 1999) (internal citations omitted).

10 Montrose Chemical Corp. v. American Motorists Insurance Co., 16 Cal. Rptr. 2d 516, 531 (Cal. Ct. App. 1993) (internal citations omitted) (emphasis added), superseded by, 18 Cal. Rptr. 2d 868 (Cal. Ct. App. 1993).

11 Okada v. MGIC Indem. Corp., 823 F.2d 276, 280 (9th Cir. 1986) (applying Hawaiian law); see also Lamar Homes Inc. v. Mid-Continent Cas. Co., 242 S.W.3d 1, 19 (Tex. 2007) (Texas's prompt payment statute specifies that insurance companies have fifteen days after receiving notice to acknowledge claim, commence investigation, and request all necessary materials from claimant).

12 Avondale Industries Inc. v. Travelers Indemnity Co., 123 F.R.D. 80, 83 (S.D.N.Y. 1988), aff'd, 887 F.2d 1200 (2d Cir. 1989).

13 McGinniss v. Employers Reinsurance Corp., 648 F. Supp. 1263, 1271 (S.D.N.Y. 1986) (internal citations omitted).

14 Village Management Inc. v. Hartford Accident & Indemnity Co., 662 F. Supp. 1366, 1374 (N.D. Ill. 1987).

15 Occidental Fire & Casualty Co. v. Cook, 435 P.2d 364, 368 (Idaho 1967). See also Cohen v. American Home Assurance Co., 258 A.2d 225, 239 (Md. 1969), which held that attorney fees may be awarded under either the implied authorization or consequential damage theory.

16 Hayseeds Inc. v. State Farm Fire & Cas., 352 S.E.2d 73, 80 (W. Va. 1986).

17 Federated Mutual Insurance Co. v. Grapevine Excavation Inc., 241 F.3d 396, 398 (5th Cir. 2001).

18 See Chernish v. Mass. Mut. Life Ins. Co., 2009 WL 385418, at *3-4 (N.D.N.Y. Feb. 10, 2009) (stating "consequential damages ... may be asserted in an insurance contract context, so long as the damages were 'within the contemplation of the parties as a probable result of a breach at the time of or prior to contracting.'") (citing Panasia Estates Inc. v. Hudson Ins. Co., 886 N.E.2d 135 [N.Y. 2008]; Bi-Economy Mkt. Inc. v. Harleysville Ins. Co. of N.Y., 886 N.E.2d 127 [N.Y. 2008]).

19 Taylor v. State Farm Fire and Casualty Co., 981 P.2d 1253, 1258 (Okla. 1999) (emphasis in original).

20 N.H. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 491:22-b (2010).

21 Va. Code Ann. § 38.2-209 (2010).

22 La. Rev. Stat. Ann. §22:1220 (2009).

23 Ariz. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 12-341.01 (2010).

24 Del. Code Ann. tit. 18, § 4102 (2010). See Galiotti v. Travelers Indem. Co., 333 A.2d 176, 178 (Del. Super. Ct. 1975) (awarding fees under § 4102 because policyholder was seeking coverage under the "property insurance" component of the policy, i.e., damage to the vehicle).

25 Okla. Stat. Ann. tit. 36, §3629(B) (2010).

26 Stauth v. National Union Fire Ins. Co., 236 F.3d 1260, 1263 (10th Cir. 2001).

27 Mobil Oil Corp. v. Maryland Casualty Co., 681 N.E.2d 552 (Ill. App. Ct. 1997).

28 Brandt v. Superior Court, 693 P.2d 796, 797 (Cal. 1985).

29 Hayseeds, supra note 16 at 79-80.

30 J.A. Appleman, Insurance Law and Practice, § 4691 (rev. ed. 1979).

31 Nolt v. U.S. Fid. and Guar. Co., 617 A.2d 578, 584 (Md. 1993) (reversing the lower court's decision and remanding, in part, to determine the policyholders' attorney fees in connection with coverage dispute).

32 Cohen v. Am. Home Assurance Co., 258 A.2d 225, 239 (Md. 1969).

33 Bankers and Shippers Ins. Co. of New York v. Electro Enterprises Inc., 415 A.2d 278, 282 (Md. 1980).

34 Id. at 283. See also Litz v. State Farm Fire and Cas. Co., 695 A.2d 566, 573 (Md. 1997) (finding insurance company liable for policyholder's attorney fees incurred "as a result of the insurer's breach of its contractual obligation to defend the insured against a claim potentially within the policy's coverage.").

35 Wheeler v. Employer's Mutual Casualty Co., 505 P.2d 768, 773 (Kan. 1973). See also Spruill Motors Inc. v. Universal Underwriters Ins. Co., 512 P.2d 403, 409 (Kan. 1973).

36 See Evans v. Provident Life & Accident Ins. Co., 815 P.2d 550 (Kan. 1991); State Farm Fire & Cas. Co. v. Liggett, 689 P.2d 1187 (Kan. 1984); Smith v. Blackwell, 791 P.2d 1343, 1349 (Kan. Ct. App. 1989); Weathers v. Am. Family Mut. Ins. Co., 777 F. Supp. 879 (D. Kan. 1991).

37 Lord v. State Automobile & Casualty Underwriters, 491 P.2d 917 (Kan. 1971).

38 Moore v. St. Paul Fire Mercury Ins. Co., 3 P.3d 81, 86 (Kan. 2000).

39 N.J. Court Rules, 1969 R. 4:42-9(a)(6) (2010). See Universal-Rundle Corp. v. Commercial Union Ins. Co., 725 A.2d 76 (N.J. Super. Ct. App. Div. 1999); Corcoran v. Hartford Fire Ins. Co., 333 A.2d 293, 299 (N.J. Super. Ct. App. Div. 1975); New Jersey Mfrs. Ins. Co. v. Consol. Mut. Ins. Co., 308 A.2d 76 (N.J. Super. Ct. Law Div. 1973).

40 Mighty Midgets Inc. v. Centennial Ins. Co., 389 N.E.2d 1080, 1085 (N.Y. 1979).

41 GRE Insurance Group v. GMA Accessories Inc., 691 N.Y.S.2d 244, 248 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. 1998). See also Mount Vernon Fire Ins. Co. v. Unjar, 575 N.Y.S.2d 694 (App. Div. 1991); U.S. Liability Ins. Co. v. Staten Island Hosp., 556 N.Y.S.2d 153 (App. Div. 1990); State Farm Fire & Cas. Co. v. Irene, 526 N.Y.S.2d 171 (App. Div. 1988); Gen. Accident Ins. Co. of Am. v. Hyatt Legal Servs., 516 N.Y.S.2d 560 (App. Div. 1987).

42 U.S. Underwriters Ins. Co. v. City Club Hotel LLC, 822 N.E.2d 777, 780 (N.Y. 2004). See also Pub. Serv. Mut. Ins. Co. v. Jefferson Towers Inc., 568 N.Y.S.2d 799 (App. Div. 1992) (awarding attorney fees coverage action where insurance company provided complete defense in underlying action); Allegany Co-Op Ins. Co. v. Williams, 628 N.Y.S.2d 900 (App. Div. 1995) (affirming the trial court's award of attorney fees for coverage action after insurance company originally undertook defense and then filed a motion to withdraw).

43 City Club, supra note 42.

44 Motorists Mutual Ins. Co. v. Trainor, 294 N.E.2d 874, 878 (Ohio 1973). See also Westfield Cos. v. O.K.L. Can Line, 804 N.E.2d 45, 56 (Ohio Ct. App. 2003) (awarding fees where insurance company acted obdurately "with a stubborn propensity for needless litigation.").

45 Olympic Steamship Co. v. Centennial Ins. Co., 811 P.2d 673, 681 (Wash. 1991) (citations omitted).

46 McGreevy v. Oregon Mutual Ins. Co., 904 P.2d 731, 738 (Wash. 1995).

47 Id. (citing Tank v. State Farm Fire & Casualty Co., 105 Wn.2d 381, 388 [Wash. 1986]). See also Am. Nat'l Fire Ins. Co. v. B&L Trucking & Constr. Co., 951 P.2d 250 (Wash. 1998).

48 Brief of Plaintiff-Appellee Liberty Mutual Ins. Co. (filed Mar. 1, 1985), at 14-15; Liberty Mutual Ins. Co. v. Continental Casualty Co., 771 F.2d 579 (1st Cir. 1985).

49 Appleman, supra note 30. See also Anderson, E.R. & J. Gold, Recoverability of Corporate Counsel Fees in Insurance Coverage Disputes, American Journal of Trial Advocacy 20:1 (Fall 1996). Mr. Gold is a partner in the firm of Anderson Kill & Olick, P.C.

50 Stichman v. Michigan Mutual Liability Co., 220 F. Supp. 848, 854 (S.D.N.Y. 1963).

51 Dale Electronics Inc. v. Federal Insurance Co., 286 N.W.2d 437, 443 (Neb. 1979).

52 Pittsburgh Plate Glass Co. v. Fidelity and Casualty Co., 281 F.2d 538 (3rd Cir. 1960).

53 Id. at 542.

54 United States v. State Farm Mutual Automobile Ins. Co., 245 F. Supp. 58 (D. Or. 1965).

55 Goldblatt Bros. v. Home Indemnity Co., 1985 WL 2114 at *1 (N.D. Ill. July 25, 1985).

56 Bailey v. United States, 260 F. Supp. 48, 54 (E.D. Va. 1966).

57 United States v. Myers, 363 F.2d 615 (5th Cir. 1966).

58 Id. at 621.

59 Travelers Insurance Co. v. State Insurance Fund, 155 Misc.2d 542 (N.Y. Ct. Cl. 1992).

60 Id. at 545.

61 See, e.g., Pub. Serv. Mut. Ins. Co. v. Goldfarb, 425 N.E.2d 810 (N.Y. 1981).

62 69th St. and 2nd Ave. Garage Assocs., L.P. v. Ticor Title Guar. Co., 622 N.Y.S.2d 13, 14 (App. Div. 1995) (emphasis added); see also Union Ins. Co. v. Knife Co., 902 F. Supp. 877, 881 (W.D. Ark. 1995) ("the conflict situation cannot be eliminated so long as the insurance company selects the counsel. It is simply a matter of human nature.").

63 San Gabriel Valley Water Co. v. Hartford Accident & Indemnity Co., 98 Cal. Rptr. 2d 807, 810 (Cal. Ct. App. 2000) (internal citations omitted) (emphasis added).

64 See, e.g., Global Investors Agent Corp. v. Nat'l Fire Ins. Co. of Hartford, 927 N.E.2d 480 (Mass. App. Ct. 2010); Curtis v. Nutmeg Ins. Co., 681 N.Y.S.2d 620 (App. Div. 1998).

65 Taco Bell Corp. v. Cont'l Cas. Co., 388 F.3d 1069, 1072 (7th Cir. 2004).

66 Id. at 1075.

67 Id. at 1075-76 (emphasis added).

68 See, e.g., Am. Serv. Ins. Co. v. China Ocean Shipping Co., 2010 WL 2487945, at *13 (Ill. App. Ct. June 16, 2010); Knoll Pharm. Co v. Auto. Ins. Co. of Hartford, 210 F. Supp. 2d 1017, 1025 (N.D. Ill. 2002) (that the policyholder paid all the defense costs "strongly implies commercial reasonableness of the fees, especially in light of the fact that ultimate recovery of the fees was uncertain because [the insurance company] refused to pay."); Stryker Corp. v. XL Ins. Am. Inc., 2008 WL 68958, at *4 (W.D. Mich. Jan. 4, 2008) ("Plaintiffs are correct that as a consequence of Defendant's decision not to defend Plaintiffs in the underlying lawsuits the settlements and defense costs for the underlying lawsuits are presumed reasonable.").

69 This article updates and expands W. Passannante and D. Shafter, "Paying by the Rules," The John Liner Review 16, no. 3 (2002): 84; and W. Passannante and R. Chung, "Who Pays for the Insurance Coverage Fight? A Majority of States Permit Recovery of Policyholder Attorney's Fees," Mealey's Attorney Fees 2, no. 3 (1999).

William G. Passannante is co-chair of Anderson Kill & Olick, P.C.'s Insurance Coverage Group. He has represented policyholders in litigation and trial in major precedent-setting cases. Passannante is a vice chair of the Professionals, Officers, and Directors Liability Committee of the Tort and Insurance Practice Section of the American Bar Association. Passannante has been a member of the Directors and Officers Liability Committee of the Insurance Committee of the Association of the Bar of the City of New York.

Marc T. Ladd is an associate with Anderson Kill & Olick, P.C. Ladd's practice concentrates in insurance recovery exclusively on behalf of policyholders. He is a graduate of St. John's University and Union College.

APPENDIX A

Potentially Helpful Authority For Policyholders Seeking Attorney Fees

About Anderson Kill & Olick, P.C.

Anderson Kill practices law in the areas of Insurance Recovery, Anti-Counterfeiting, Antitrust, Bankruptcy, Commercial Litigation, Corporate & Securities, Employment & Labor Law, Health Reform, Intellectual Property, International Arbitration, Real Estate & Construction, Tax, and Trusts & Estates. Best-known for its work in insurance recovery, the firm represents policyholders only in insurance coverage disputes, with no ties to insurance companies and no conflicts of interest. Clients include Fortune 1000 companies, small and medium-sized businesses, governmental entities, and nonprofits as well as personal estates. Based in New York City, the firm also has offices in Newark, NJ, Philadelphia, PA, Stamford, CT, Ventura, CA and Washington, DC. For companies seeking to do business internationally, Anderson Kill, through its membership in Interleges, a consortium of similar law firms in some 20 countries, assures the same high quality of service throughout the world that it provides itself here in the United States.

Anderson Kill represents policyholders only in insurance coverage disputes, with no ties to insurance companies, no conflicts of interest, and no compromises in its devotion to policyholder interests alone.

The information appearing in this article does not constitute legal advice or opinion. Such advice and opinion are provided by the firm only upon engagement with respect to specific factual situations