With corporations in constant litigation, and in some instances in specious lawsuits from aggressive litigants, depositions of high-level executives, "apex depositions," have become profoundly burdensome, costly, and impractical. (An apex deposition is a deposition of the persons at the apex of the corporate tree). Rather than taking the depositions of employees and/or executives with first-hand knowledge of the relevant facts, plaintiff lawyers sometimes seek apex depositions of high-level executives, who offer little to no additional information, knowing that such depositions are disruptive to top executives and the companies they lead.

In such instances, companies can invoke the protections of Rule 26(c)(1)(A) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, which allows a court to "issue an order to protect a party or person from annoyance, embarrassment, oppression, or undue burden or expense," by barring the deposition of certain individuals. The party seeking the protective order bears the burden of showing good cause exists to issue the order. However, most jurisdictions have also established a doctrine that prevents the deposition of top executives, known as "the apex deposition rule."

A. Apex depositions are generally unnecessary and barred

Because apex depositions rarely reveal any significant information in discovery, some jurisdictions presumptively bar them due to the unnecessary distractions they create on top executives. And, even when apex depositions are noticed by an aggressive litigant, district courts often review the potential for oppression, inconvenience, and burden on the company, and if necessary, issue a protective order to prevent the deposition.

But there is a divide between the circuits about the manner by which apex depositions are quashed. Some courts view apex depositions as part of the traditional discovery process and require that a company opposing the apex deposition do so via motion practice. Other courts have established apex deposition rules that require less hassle to oppose an apex deposition without resorting to motions for protective orders and/or motions to quash until other avenues — such as deposing a lower-ranked executive — are taken first. If you are an apex executive, your likelihood of being deposed may depend on if you live in a state that is friendly or unfriendly to apex depositions.

B. Lucky executives in jurisdictions with a presumption against apex depositions

Several circuits have taken a proactive approach in precluding depositions of high-level executives with no personal knowledge of the facts at issue. For example, the 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals (Illinois, Indiana, and Wisconsin) emphasized the importance of "curbing abuse" of questioning that "may unreasonably annoy, embarrass, or oppress" a high-level executive. Eggleston v. Chicago Journeymen Plumbers' Loc. Union No. 130, U. A., 657 F.2d 890, 904 (7th Cir. 1981).

The 1st U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals (Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Puerto Rico, and Rhode Island) confirmed this view in Braga v. Hodgson, where a litigant "put forth no evidence or plausible argument suggesting that a deposition of [the high-level executive] was reasonably calculated to lead to other discoverable materials regarding the party's claims." 605 F.3d 58, 60 (1st Cir. 2010). The 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals (Alabama, Florida, and Georgia) applied a similar approach, where the harm from the apex deposition was disproportionate to the discovery request, since the information sought would not make the plaintiff's claims any "more or less true." West v. City of Albany, Georgia, 830 F. App'x 588, 593 (11th Cir. 2020).

To promote less intrusive measures than an apex deposition, the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals (Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas) has also precluded apex depositions, especially when a litigant sought an apex deposition before deposing lower-ranked employees and/or supervisors with more relevant knowledge. Salter v. Upjohn Co., 593 F.2d 649 (5th Cir. 1979). The 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals (Kentucky, Michigan, Ohio, and Tennessee) clarified the reason for the apex doctrine, noting that a plaintiff should generally not be permitted to "go fishing," and the difficulty for high-level personnel to schedule a deposition because of their duties can be enough to prevent their apex deposition entirely. Anwar v. Dow Chem. Co., 876 F.3d 841, 846 (6th Cir. 2017).

Taking the guidance from the 5th and 6th Circuits, the 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals (Oklahoma, Kansas, New Mexico, Colorado, Wyoming, and Utah) even deemed apex depositions a "severe hardship," precluding an apex deposition of an high-level executive at IBM, due to the executive's testimony of having no personal knowledge of the relevant facts, the plaintiff's failure to depose the appropriate supervisors first, the location and timing of the deposition, and the executive's prescheduled meetings with senior management. Thomas v. Int'l Bus. Machines, 48 F.3d 478, 483 (10th Cir. 1995).

Although the 5th, 6th, and 10th Circuits instruct plaintiffs to take the deposition of a lower ranked executive before taking an apex deposition, some courts do not assume hardship merely from their role as a high-level executive and require at least some showing of the burden the executive would face. But where the executive attests to no personal knowledge, harms are easily recognized. For example, in Elvis Presley Enterprises. v. Elvisly Yours, Inc., the court found an undue burden based solely on the executive's sworn testimony of her lack of personal knowledge and belief that the plaintiff intends to harass and annoy her. 936 F.2d 889, 894 (6th Cir.1991).

C. Unlucky executives in jurisdictions without a presumption against apex depositions

Conversely, rather than taking preemptive action, some circuits are less favorable to protecting top executives and only bar apex depositions where the harm to the executive meets a higher threshold. However, the circuits differ as to the correct standard for such a threshold. For instance, the 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals (Connecticut, New York, and Vermont) failed to recognize an injury where the executive testified to the potential harms they may face, not any concrete harms, and alleged the plaintiff merely sought to harass them. Brown v. Astoria Fed. Sav. & Loan Ass'n, 444 F. App'x 504, 505 (2d Cir. 2011).

The 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals (Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, and West Virginia) on the other hand, developed a more rigorous standard in which they applied the balancing test in Rule 25(b)(1) into Rule 26(c) to hold a protective order should only be granted where "the burden or expense of the proposed discovery outweighs its benefit." Nicholas v. Wyndham Int'l, Inc., 373 F.3d 537, 540 (4th Cir. 2004).

More narrowly, the 3rd, 8th, and 9th Circuits (Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware, and the Virgin Islands; Minnesota, Iowa, North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Missouri, and Arkansas; Alaska, Arizona, California, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington) held that there must be a particularized harm that is: (1) not too broad, (2) significant, and (3) proven by specific examples. Miscellaneous Docket Matter No. 1 v. Miscellaneous Docket Matter No. 2, 197 F.3d 922, 926 (8th Cir. 1999).

Narrower still, the 3rd and 9th Circuits added a second prong to the test: if there is a particularized harm, then the private and public interests should be balanced. See Cipollone v. Liggett Grp., Inc., 785 F.2d 1108, 1121 (3d Cir. 1986); Smith v. BIC Corp., 869 F.2d 194, 201 (3d Cir. 1989); Glenmede Tr. Co. v. Thompson, 56 F.3d 476, 483 (3d Cir. 1995); Phillips ex rel. Ests. Of Byrd v. Gen. Motors Corp., 307 F.3d 1206, 1211 (9th Cir. 2002); In re Roman Cath. Archbishop of Portland in Oregon, 661 F.3d 417, 424 (9th Cir. 2011); Foltz v. State Farm Mut. Auto. Ins. Co., 331 F.3d 1122, 1136-37 (9th Cir. 2003).

D. Navigating the divide: options for the apex executive on apex depositions

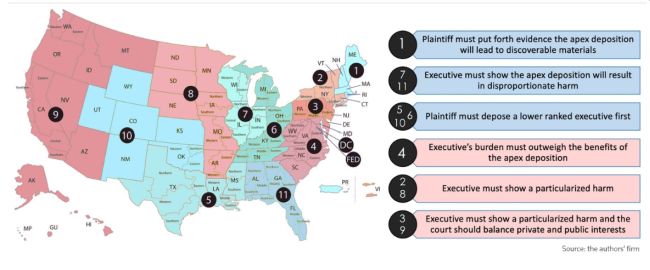

Although the Circuits greatly differ on the suitable standard in granting protective orders to prevent apex deposition, all Circuits have provided some guidance as to what parties must prove to prevent depositions of their high-level executives. The figure above demonstrates the Circuit split in granting such orders. The Circuits shaded in blue are the most aggressive in stopping apex depositions. The 1st Circuit, as the most protective of apex executives, requires that a plaintiff provide evidence that the desired apex deposition will lead to new discoverable information.

At the 7th and 11th Circuits, an executive merely needs to show disproportionate harm to prevent an apex deposition. After a showing of harm, the 5th, 6th, and 10th Circuits require that a plaintiff first depose a lower ranked executive. Shaded in pink are the Circuits with a higher harm threshold. The 4th Circuit prevents apex depositions, only where the executive's burden outweighs its benefits. The 2nd and 8th Circuits require the executive show a particularized harm, along with the 3rd and 9th Circuits, which additionally require a balancing of the public and private interests.

Knowing the rules in a given jurisdiction is essential to prevent unnecessary and burdensome depositions. Relatedly, in some jurisdictions, explaining the specific inconvenience of an executive's deposition is crucial to avoiding apex depositions. Thus, although all of the Circuits have varying rules for apex depositions, with preparation, and even in those Circuits with strict legal tests, a party can almost always prevent an apex deposition of a high-level executive, unless the executive has personal knowledge of the issues.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.