Trade dress often soars above the intellectual property landscape because it has the power to protect a distinctive product design for as long as the design is in use. It's the icing on the cake that can provide an extra layer of protection for a company's products. But where the design, taken as a whole, is functional, it cannot be protected as trade dress. Accordingly, as a recent Federal Circuit decision illustrates, a company's decision to tout the functionality of a product in order to obtain patent protection can ruin its chances of securing trade dress protection for the look and feel of a product.

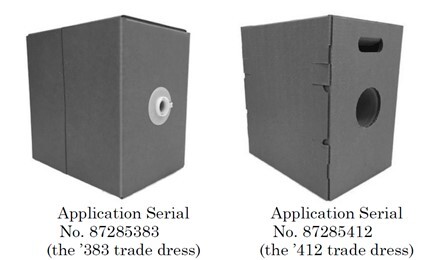

Reelex Packaging Solutions, Inc. designs and manufactures winding machines used to package cables and wires into its "Reelex Boxes." Asserting that the designs of its boxes were distinctive, Reelex filed applications with the USPTO to register these two designs as trade dress:

The trade dress applications were refused, however, on the basis that the two designs, taken as a whole, were functional—and thus legally unable to be protected as trade dress. The USPTO's decision was based in large part on statements Reelex had made either to obtain patent protection and/or in the company's advertising. In its applications for utility patents, for example, Reelex had made statements regarding the products' functionality both in the disclosures and in describing the patents' preferred embodiments. Similarly, in its advertising, Reelex had described its boxes as featuring "tangle-free technology" that allowed the cables and wires they contained to be dispensed without kinking or tangling.

Reelex appealed the Examining Attorney's refusals to the TTAB, which affirmed the decisions. Reelex then appealed to the Federal Circuit. The Federal Circuit, reviewing the TTAB's legal determination de novo and its factual findings for substantial evidence, affirmed.

Initially, the Federal Circuit went through the TTAB's decision on functionality, noting that that it had followed the Federal Circuit's prior decision in In re Morton-Norwich Products, Inc., where four factors had been set out as relevant to the functionality issue. The first of these factors is the existence of a utility patent that discloses the utilitarian (functional) advantages of the design. That didn't bode well for Reelex, since it had obtained five utility patents on its box design, and the TTAB had found that each of these patents contained disclosures that heavily stressed functionality:

- One patent described how the tube and collar in the '383 design could be snap-fastened together to smoothly guide the cable and wire through the tube "to prevent damage" to the box.

- Another patent explained that the specific dimensions of the Reelex Boxes served to fit the diameters of coils, and that the cutout handle in the '412 design enabled the box to be transported.

- Yet another patent highlighted the advantages of using larger openings in the '412 design to avoid kinking, and also noted that certain types of cables have "inherent residual twist characteristics" that require a much larger hole and tube combination.

- Another patent noted the "usefulness" of a cut-out handle in the '412 design to help with the carrying and transporting the box.

- The final patent disclosed how common it is to wind wires and cables in a figure-8 configuration and house them in a container for the purpose of storing, shipping, and handling them "in a fashion ready for application."

The Federal Circuit agreed, finding "no error in the Board's functionality analysis." Accordingly, the court held that the TTAB's decision regarding the first factor—that Reelex's patents showed that the designs of its two boxes were "dictated by their function"—was supported by substantial evidence.

The court then addressed the second Morton-Norwich factor—whether the applicant's advertising touts the utilitarian advantages of the design—and noted that the TTAB had found that Reelex's advertisements explicitly and repeatedly touted the figure-8 pattern for "tangle-free" dispensing of cables and wires. Reelex's promotion of the superior "recyclability, stacking, shipping, and storage of the boxes," all of which are utilitarian advantages of the designs, further tilted the scale towards functionality. And again, the court found that this finding was supported by substantial evidence.

Turning to the third factor—whether alternative designs exist—the Federal Circuit observed that the TTAB had been correct in saying that if functionality was found based on "other considerations," this factor need not be considered. Nonetheless, the court went on to reject Reelex's argument that the Board did not sufficiently consider the declaration of a longtime employee who had asserted that alternative designs existed. In fact, the court said, the TTAB had "expressly considered" the employee's declaration, and simply declined to "give much weight" to it. As the court observed, in fact, while the employee had asserted in his declaration that certain aspects of the box designs were "merely ornamental," that assertion was contradicted by statements in the patents themselves. And the TTAB has "broad discretion" to weigh the evidence presented, including the declaration, the court observed. Thus, the court found "no error" in the TTAB's decision that the designs were functional.

Having already concluded that the TTAB reached the correct decision, the court apparently saw no need to discuss the fourth (and final) Morton-Norwich factor—whether the designs resulted from a comparatively simply or inexpensive method of manufacturing. Earlier, however, the court had noted that the Board TTABhad found there was "no evidence of record" on this factor.

The lesson of In re Reelex comes less from the fact that the Federal Circuit upheld the TTAB's finding of functionality in this case, a determination that was fact-based and thus potentially difficult to apply in other cases. Rather, it comes from the decision's reminder that wherever utility patents and trade dress converge, careful planning and drafting of both the utility patents and trademark applications is essential. Brand owners should make sure that the trade dress application focuses on the non-functional elements that are not claimed as functional in a utility application.

This case is In re Reelex Packaging Solutions, 2020 WL 6495532 (Fed. Cir. November 5, 2020).

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.