The artificial intelligence (AI) global supply chain includes a number of operators—such as developers, providers, and users—and countries are taking different approaches to regulating these actors.

The EU developed specific obligations for each of these AI operators, with Canada and Australia heading towards this approach. The US and UK opted for a more flexible approach to AI regulation by relying on a combination of AI principles and a context-specific framework to ensure the safe and trustworthy supply of AI in the marketplace. Singapore, on the other hand, takes a neutral approach to AI oversight by providing general considerations and a toolkit that AI actors can voluntarily use, as relevant to their operations.

These varying approaches to AI regulation each carry different benefits. For example, while the EU's approach is more stringent, it provides greater legal certainty for operators in the AI supply chain. The US and UK approach provides some legal certainty to organizations as well, depending on their sector and industry, while at the same time providing flexibility on how to operationalize broad AI principles. On the opposite end of the spectrum, Singapore's voluntary framework gives the greatest degree of flexibility to AI operators, but does not provide clear rules for organizations that are investing in developing and using AI systems.

This article describes the different approaches some countries have taken in regulating the AI supply chain, and provides takeaways for multinational companies to consider as they develop or use AI systems.

EU Approach to Regulating the AI Supply Chain

The EU's Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council Laying Down Harmonised Rules on Artificial Intelligence (EU AI Act) creates different obligations on operators depending on their role in the AI supply chain and the potential risks of their AI systems.

These operators include:

- A provider that develops—or has developed—an AI system or general purpose AI (GPAI) model and places it on the EU market or puts it into service under its own name or trademark;

- A deployer that uses the AI system—excluding personal non-professional use;

- An importer that first makes a non-EU company's AI system available in the EU market; and

- A distributor that makes an AI system available in the EU market, but is not otherwise a provider or importer.

The following chart specifies the various rules that operators must follow depending on their AI systems' risk level. Note that the high-risk AI systems referenced below include: (1) AI systems in certain regulated products or their safety components; (2) biometrics; (3) critical infrastructure; (4) education and vocational training; (5) employment, workers management and access to self-employment; (6) essential private and public services and benefits; (7) law enforcement; (8) migration, asylum and border control management; and (9) administration of justice and democratic processes.

|

Provider |

Deployer |

|

Prohibited AI Systems Not place on the market or put into service AI systems: (a) that deploy subliminal techniques beyond a person's consciousness or purposefully manipulative or deceptive techniques; (b) that exploit the vulnerabilities of a person or group due to their age, disability or a specific social or economic situation; (c) that categorize individuals based on their biometric data to deduce or infer sensitive characteristics; (d) for social scoring; (e) for real-time remote biometric identification in publicly accessible spaces for law enforcement purposes; (f) for predictive policing; (g) for creating or expanding facial recognition databases through the untargeted scraping of facial images from the internet or CCTV footage; and (h) for emotion recognition in the workplace and education institutions, except for medical or safety reasons (i.e., monitoring the tiredness levels of pilots). |

Prohibited AI Systems Not use AI systems: (a) that deploy subliminal techniques beyond a person's consciousness or purposefully manipulative or deceptive techniques; (b) that exploit the vulnerabilities of a person or group due to their age, disability or a specific social or economic situation; (c) that categorize individuals based on their biometric data to deduce or infer sensitive characteristics; (d) for social scoring; (e) for real-time remote biometric identification in publicly accessible spaces for law enforcement purposes; (f) for predictive policing; (g) for creating or expanding facial recognition databases through the untargeted scraping of facial images from the internet or CCTV footage; and (h) for emotion recognition in the workplace and education institutions, except for medical or safety reasons (i.e., monitoring the tiredness levels of pilots). |

|

High-Risk AI Systems

|

High-Risk AI Systems

|

|

Limited-Risk AI Systems

|

Limited-Risk AI Systems

|

|

Importer |

Distributor |

|

Prohibited AI Systems Not place on the EU market AI systems: (a) that deploy subliminal techniques beyond a person's consciousness or purposefully manipulative or deceptive techniques; (b) that exploit the vulnerabilities of a person or group due to their age, disability or a specific social or economic situation; (c) that categorize individuals based on their biometric data to deduce or infer sensitive characteristics; (d) for social scoring; (e) for real-time remote biometric identification in publicly accessible spaces for law enforcement purposes; (f) for predictive policing; (g) for creating or expanding facial recognition databases through the untargeted scraping of facial images from the internet or CCTV footage; and (h) for emotion recognition in the workplace and education institutions, except for medical or safety reasons (i.e., monitoring the tiredness levels of pilots). |

Prohibited AI Systems Not make AI systems available on the EU market: (a) that deploy subliminal techniques beyond a person's consciousness or purposefully manipulative or deceptive techniques; (b) that exploit the vulnerabilities of a person or group due to their age, disability or a specific social or economic situation; (c) that categorize individuals based on their biometric data to deduce or infer sensitive characteristics; (d) for social scoring; (e) for real-time remote biometric identification in publicly accessible spaces for law enforcement purposes; (f) for predictive policing; (g) for creating or expanding facial recognition databases through the untargeted scraping of facial images from the internet or CCTV footage; and (h) for emotion recognition in the workplace and education institutions, except for medical or safety reasons (i.e., monitoring the tiredness levels of pilots). |

|

High-Risk AI Systems

|

High-Risk AI Systems

|

The EU AI Act also clarifies that, under certain circumstances, a distributor, importer and deployer can be a high-risk AI system provider in the AI supply chain. As described in Article 28 of the EU AI Act, these circumstances include if they:

- Put their name or trademark on a high-risk AI system;

- Make substantial modification to the high-risk AI system, which means that the AI system has been changed in a manner that is not foreseen or planned in the provider's initial conformity assessment and results in a modification to the AI system's intended purpose; or

- Modify the intended purpose of an AI system (including GPAI system) if it was previously not a high-risk AI system, but the modification makes it high risk.

If any of these circumstances are met, the original provider is no longer considered a provider of the AI system under the EU AI Act, and these obligations shift to the distributor, importer or deployer. In addition, for high-risk AI systems that are safety components of certain regulated products, the manufacturer of those products are also considered a provider of a high-risk AI system under the EU AI Act if the AI system is placed on the market together with the product under its name or trademark or put into service under its name or trademark after the product has been placed on the market.

Providers of GPAI models are also subject to specific requirements under the EU AI Act. These requirements vary depending on whether the GPAI model carries systemic or non-systemic risk. GPAI models with systemic risk are trained using a total computing power of more than 10^25 floating point operations (FLOPs), which reflects the most powerful GPAI models.

The chart below describes the obligations of non-systemic and systemic risk GPAI model providers under the EU AI Act.

|

Non-Systemic Risk GPAI Model |

Systemic Risk GPAI Model |

|

|

Canada Opting for EU Approach

Similar to the EU AI Act, Canada is also looking to distinguish the obligations of AI operators in the supply chain. Under the Artificial Intelligence and Data Act (AIDA), which the Government of Canada introduced in June 2022 as part of Bill C-27, there will be defined roles for businesses that design or develop, make available for use and manage the operation of high-impact AI systems. The AIDA Companion Document notes as follows with respect to division of responsibility along the AI supply chain:

- Businesses who design or develop a high-impact AI system would be expected to take measures to identify and address risks with regards to harm and bias, document appropriate use and limitations, and adjust the measures as needed.

- Businesses who make a high-impact AI system available for use would be expected to consider potential uses when deployed and take measures to ensure users are aware of any restrictions on how the system is meant to be used and understand its limitations.

- Businesses who manage the operations of an AI system would be expected to use AI systems as indicated, assess and mitigate risk, and ensure ongoing monitoring of the system.

The AIDA Companion Document adopts distinct roles for operators in the AI supply chain because each actor has different tasks within its control. For example, the document notes that developers of general-purpose AI systems need to ensure that risks related to bias or harmful content are documented and addressed because end users have limited influence on how such systems function. In addition, the document explains that the entity managing the AI system's operation is better suited to conduct post-deployment monitoring because AI developers and designers are not practically situated to do so.

On Sept. 27, 2023, Canada also released a Voluntary Code of Conduct on the Responsible Development and Management of Advanced Generative AI Systems, which companies may implement ahead of AIDA coming into force. Canada's voluntary code of conduct identifies the AI principles businesses should commit to—i.e., accountability, safety, fairness and equity, transparency, human oversight and monitoring, and validity and robustness—and explains how these principles should be implemented depending on the operator's role.

Thus, with Canada opting to provide clear obligations for operators in the AI supply chain and focusing on high-impact AI systems, it is leaning towards the EU model for AI regulation.

Australia May Follow Similar Path

Australia is also working on developing AI regulations that appear to follow the EU's lead. After publishing its discussion paper on safe and responsible AI on June 1, 2023, the Australian government sought consultation from stakeholders on steps it can take to mitigate the potential risks of AI. After a year of consultations, Australia's Department of Industry Science and Resources published its interim response (Interim Response) on Jan. 17, 2024.

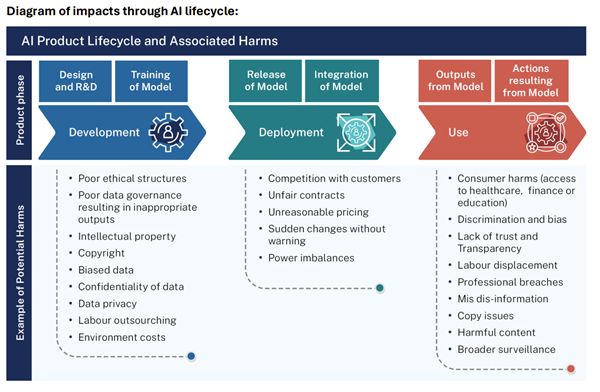

In the Interim Response, there was some indication that Australia may delineate responsibilities along the AI supply chain for high-risk AI systems, similar to the EU AI Act. The Australian government noted that it "recognises the need to consider specific obligations for the development, deployment and use of frontier or general-purpose models." The Interim Response also identifies the unique risks present during the AI system's development, deployment and use stages, as it outlined in the chart below.

While Australia is still early in its AI regulatory process, there is some indication in the Interim Response that it may align with the EU AI Act by adopting a risk-based approach to AI regulation with clear lines of responsibility. For now, however, Australia relies on existing laws and a voluntary AI Ethics Framework to regulate AI.

The AI Ethics Framework is composed of eight principles that require AI systems to:

- Be beneficial for individuals, society and the environment;

- Respect human rights, diversity and the autonomy of individuals;

- Be inclusive and accessible, and not involve or result in unfair discrimination against individuals, communities or groups;

- Respect and uphold privacy rights and data protection, and ensure the security of data;

- Reliably operate in accordance with their intended purpose;

- Be transparent and explainable;

- Be contestable; and

- Have people responsible for the different phases of the AI system lifecycle, provide sufficient human oversight, and be accountable for the outcomes of the AI systems.

US & UK Aim for a Sector-Specific AI Regulation

The US and UK do not currently have a comprehensive AI law that provides clear legal obligations for each operator in the AI supply chain, like the EU AI Act. Rather, the US and UK have issued guidelines—The White House Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights and A Pro-Innovation Approach to AI Regulation, respectively—that outline the AI principles operators should abide by for safe and trustworthy AI.

In addition, the US and UK intend to regulate AI based on an organization's sector and context of AI development and use. For example, in the US, the Federal Trade Commission, Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, Department of Justice's Civil Rights Division, and Consumer Financial Protection Bureau issued a joint statement on April 25, 2023, indicating their intent to regulate AI within their sectors, such as consumer protection, education, criminal justice, employment, housing, lending, voting, and competition. Through their existing enforcement powers, these US regulators intend to monitor both the development and use of AI systems through existing laws, which do not clearly distinguish the specific roles and obligations of actors in the AI supply chain, like the EU AI Act.

On Oct. 30, 2023, the White House also directed various agencies through its Executive Order on the Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Development and Use of Artificial Intelligence to develop best practices and guidelines relevant to their regulated sectors, underscoring the US's sector and context-specific approach to AI regulation. The one exception, however, is the Executive Order's direction for additional guidelines, procedures and processes for developers of dual-use foundation models, including requirements for ongoing reporting and red-team testing. Thus, it is possible that the US may provide clear guidelines with respect to dual-use foundation models, which serve as the bedrock for downstream AI operators.

In the UK, the government published its response to the A Pro-Innovation Approach to AI Regulation white paper on Feb. 6, 2024. In the response, the UK government noted that regulators, such as the Competition and Markets Authority, Information Commissioner's Office, Office of Gas and Electricity Markets and Civil Aviation Authority, and Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency, are already incorporating the UK principles in their work and that the UK is committed to a combined cross-sectoral principles and a context-specific framework for AI regulation. Under the UK-approach, the government believes "that it is more effective to focus on how AI is used within a specific context than to regulate specific technologies . . . because the level of risk will be determined by where and how AI is used."

That said, while the UK is committed to a more flexible approach to AI regulation, the government notes that the potential risks of highly capable general-purpose AI systems may not be effectively mitigated by existing regulation, which challenges the UK's context-based framework. The UK government also left open the possibility of considering "the role of other actors across the value chain, such as data or cloud hosting providers, to determine how legal responsibility for AI may be distributed most fairly and effectively."

In sum, while the US and UK do not currently delineate the responsibilities of operators in the AI supply chain, similar to the EU AI Act, it is possible that they may issue further guidance on this topic, particularly with respect to foundation models. Indeed, there is already a trend under US state AI bills to distinguish the obligations of deployers and developers (e.g., California AB331, Washington HB1951, and Virginia HB747). Thus, at least on the US state level, we may see AI laws similar to the EU AI Act, but lighter in scope.

Singapore Adopts Flexible AI Framework

Singapore takes a neutral approach to AI regulation, without specifically delineating the roles and obligations of operators in the AI supply chain. In its Model Artificial Intelligence Governance Framework, Second Edition, Singapore's Personal Data Protection Commission (PDPC) provides a voluntary AI framework that is algorithm, technology, sector and business-agnostic in its approach.

The framework is flexible and provides broad considerations that developers, deployers and others in the AI supply chain may incorporate in their AI governance program, as relevant to their organization. Through this framework and its AI Verify program—an AI governance testing and software toolkit—Singapore hopes to take a balanced approach to regulating AI that will facilitate innovation, safeguard consumer interests, and serve as a common global reference point.

Takeaways for Multinational Companies

Multinational corporations that intend to develop, import, distribute or use AI systems in the global economy will need a harmonized plan to address varying global approaches to AI oversight. Below are some of the takeaways to consider:

- Understand the common global AI principles and operationalize

them into practice. For example, countries on six continents have

committed to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and

Development's (OECD) five values-based AI principles. These

principles include ensuring that AI systems:

- Are trustworthy and contribute to overall growth and prosperity for all, including individuals, society and the planet, and advance global development objectives;

- Should be designed in a way that respects the rule of law, human rights, democratic values and diversity, and include appropriate safeguards to ensure a fair and just society;

- Are transparent and explainable;

- Are robust, secure and safe; and

- Operators are accountable for their proper functioning.

Countries that have adopted a principles-based approach incorporate a variation of these OECD principles, which make them good guideposts.

- Adopt an AI governance plan that is commensurate with your role in the AI supply chain. With the EU AI Act being the most stringent AI law in the world, adopting an AI governance plan consistent with this regulation based on your role is a good baseline.

- Understand existing laws of general applicability that may apply to AI systems, depending on your organization's sector and context of development and use. This also includes complying with global data privacy laws, which regulate the use of personal data, which is often used to train, test, validate and deploy AI systems.

Originally published by Bloomberg Law.

Visit us at mayerbrown.com

Mayer Brown is a global services provider comprising associated legal practices that are separate entities, including Mayer Brown LLP (Illinois, USA), Mayer Brown International LLP (England & Wales), Mayer Brown (a Hong Kong partnership) and Tauil & Chequer Advogados (a Brazilian law partnership) and non-legal service providers, which provide consultancy services (collectively, the "Mayer Brown Practices"). The Mayer Brown Practices are established in various jurisdictions and may be a legal person or a partnership. PK Wong & Nair LLC ("PKWN") is the constituent Singapore law practice of our licensed joint law venture in Singapore, Mayer Brown PK Wong & Nair Pte. Ltd. Details of the individual Mayer Brown Practices and PKWN can be found in the Legal Notices section of our website. "Mayer Brown" and the Mayer Brown logo are the trademarks of Mayer Brown.

© Copyright 2024. The Mayer Brown Practices. All rights reserved.

This Mayer Brown article provides information and comments on legal issues and developments of interest. The foregoing is not a comprehensive treatment of the subject matter covered and is not intended to provide legal advice. Readers should seek specific legal advice before taking any action with respect to the matters discussed herein.