Seldom does an obscure provision in a California statute provoke as much mainstream interest as what is colloquially known as the "Builder's Remedy." Generally, the Builder's Remedy provisions of the Housing Accountability Act, or "HAA," apply when a city or county has not adopted a housing element that is in substantial compliance with state Housing Element Law. When the provisions apply, they strip the local government of its authority to disapprove a housing development project based on inconsistencies with the local zoning ordinance and general plan land use designation. The Builder's Remedy is a powerful tool for housing developers because it serves as both sword and shield that can be used against the common not-in-my-backyard mentality and other forms of opposition to proposed projects.

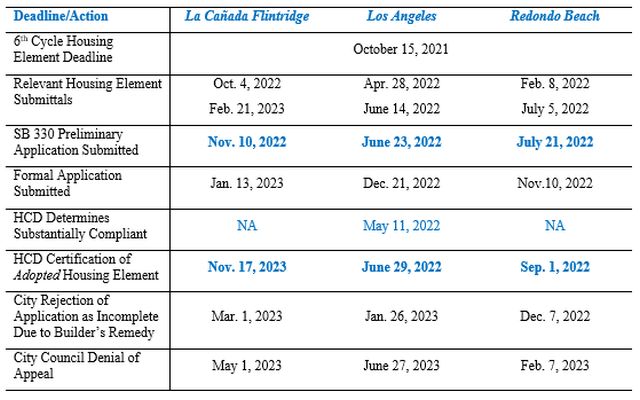

The California Department of Housing and Community Development ("HCD") has provided formal guidance on important aspects of the Builder's Remedy and Housing Element Law. HCD has opined that a jurisdiction's housing element does not achieve substantial compliance until the element is certified by HCD and that a "preliminary application" pursuant to Senate Bill ("SB") 330 vests such noncompliance for the duration of the project entitlement process. (See HCD Notice of Violation to La Cañada Flintridge, June 2023.) In addition to this guidance being helpful to project applicants and local jurisdictions, under traditional rules of jurisprudence, courts should defer to this guidance. Until recently, however, courts had not interpreted the issues covered in the guidance. In three separate decisions in February and March of this year, the Los Angeles County Superior Court concurred with HCD on both issues and addressed other important questions regarding use of the Builder's Remedy. These trial court decisions are not binding precedent, but they provide a sense of how other courts may decide controversial issues regarding the Builder's Remedy facing both developers and jurisdictions. These decisions are: New Commune DTLA LLC v. City of Redondo Beach, decided on February 8, 2024, 600 Foothill Owner, L.P. v. City of La Cañada Flintridge, decided on March 4, 2024 (and in which Cox Castle now represents the Petitioner), and Janet Jha v. City of Los Angeles, decided on March 5, 2024.

Relevant Facts

The three cases share similar facts, as each involved the filing of a SB 330 preliminary application prior to HCD certification of the jurisdiction's housing element, and each also involved city assertions that the applicants' formal development applications were incomplete, appeals of the incompleteness determinations, and denials of the appeals.

The Redondo Beach decision involves a trial court denial of a petition for writ of mandate in connection with Redondo Beach's denial of Petitioner New Commune DTLA LLC's housing development project located in the Coastal Zone on the grounds that the Petitioner could not use the Builder's Remedy.

The La Cañada Flintridge decision involves a trial court order granting in part petitions for writ of mandate in two cases each challenging La Cañada Flintridge's denial of a housing development project on the grounds that the developer could not use the Builder's Remedy. The Attorney General and HCD both intervened to challenge La Cañada's decision.

The Los Angeles decision involves a trial court denial of a demurrer to a claim that Los Angeles violated the HAA by failing to process a Builder's Remedy application.

Key Rulings

- A Housing Element Is Not Substantially Compliant Until Certified By HCD

Housing Element Law specifies a process for jurisdictions to prepare and submit housing elements to HCD for review and determination of substantial compliance with Housing Element Law. Many jurisdictions have claimed the Builder's Remedy is unavailable based on so-called "self-certification" of housing elements. In other words, the jurisdiction itself finds that its housing element substantially complies with the law and claims that decision forecloses use of the Builder's Remedy prior to HCD's certification of the housing element. Consistent with HCD's guidance that a housing element is not substantially compliant until certified by HCD, these cases make clear that a jurisdiction may not "self-certify" its housing element.

In the Redondo Beach decision, even though the Redondo Beach adopted the version of its housing element ultimately certified by HCD before petitioner New Commune DTLA LLC submitted its SB 330 preliminary application, the court held that Redondo Beach needed HCD's final compliance determination (which came after submission of the SB 330 preliminary application) to have a substantially compliant housing element for purposes of the Builder's Remedy.

Similarly, in La Cañada Flintridge, the court clarified that, if La Cañada disagreed with HCD's noncompliance finding, La Cañada should have adopted its housing element without changes and thereafter sought a judicial determination that its housing element substantially complied with state law. The court concluded that La Cañada lacked authority under the HAA or Housing Element Law to revise and adopt its housing element and "self-certify" its compliance.

The Los Angeles decision reached the same conclusion. Los Angeles maintained that the Builder's Remedy was unavailable to petitioner Janet Jha because Los Angeles had a substantially compliant housing element on the date that Jha submitted a SB 330 preliminary application. By that date, Los Angeles had an adopted housing element that was substantially the same as the prior draft version HCD determined to be substantially compliant, but HCD had not yet certified the adopted version. The court held that HCD may only find a jurisdiction's housing element substantially compliant with Housing Element Law after the jurisdiction complies with a process that includes submittal of the adopted housing element to HCD and HCD's review of the adopted housing element. As a result, the availability of the Builder's Remedy continued until the date HCD certified Los Angeles' adopted housing element.

- An SB 330 Preliminary Application Vests Housing Element Non-Compliance

The HAA provides that the submittal of an SB 330 preliminary application "vests" the local rules applicable to a project as those in effect at the time of the submittal (notwithstanding any subsequent changes to the local rules during the project processing). A critical issue with the Builder's Remedy is the ability to vest a jurisdiction's non-compliant housing element by filing an SB 330 preliminary application, such that the Builder's Remedy applies at the time a project is considered for approval even if the jurisdiction has achieved substantial compliance in the interim. In all three decisions, the court agreed with HCD's guidance that an SB 330 preliminary application vests a jurisdiction's housing element noncompliance for the duration of project processing.

- Refusal to Process Is A "Disapproval" Under The HAA

The HAA defines disapproval of a housing development project to include any instance in which the local agency "[v]otes on a proposed housing development project application and the application is disapproved, including any required land use approvals or entitlements necessary for the issuance of a building permit." (Gov. Code, § 65589.5(h)(6).) In the La Cañada Flintridge decision, the developer argued La Cañada's refusal to process the application constituted a "disapproval" under the HAA. La Cañada argued that there was no disapproval because it did not deny the underlying project entitlements. The court rejected La Cañada's narrow interpretation of the HAA and found that La Cañada disapproved the project when it declined to process the Builder's Remedy application. The court in the Redondo Beach decision reaches the same conclusion in response to substantially similar arguments.

- A Jurisdiction That Misses The Housing Element Statutory Deadline Is Not In Substantial Compliance Until It Rezones

Under the Housing Element Law, a jurisdiction that does not have a substantially compliant housing element (as determined by HCD) within 120 days of the statutory deadline must rezone sufficient sites to accommodate its housing need within one year, and if the jurisdiction adopts its housing element more than one year after the statutory deadline, it cannot be in substantial compliance until it has completed the required rezoning. In the La Cañada Flintridge decision, La Cañada failed to secure HCD certification within 120 days of the October 2021 statutory deadline and likewise failed to complete the required rezonings until September 2023 (the rezonings were deemed substantially compliant by HCD in November 2023), well beyond the one-year deadline and after 600 Foothill submitted its SB 330 preliminary application. On this basis, the court held that La Cañada did not have a substantially compliant housing element at the time of the SB 330 preliminary application, and the Builder's Remedy therefore applied to the project. In the Redondo Beach decision, the court noted that the city's failure to timely rezone was another fact supporting its conclusion that the city lacked a compliant housing element on the date New Commune DTLA LLC submitted its SB 330 preliminary application.

- HCD's Legal Interpretations And Determinations Regarding Substantial Compliance Are Entitled to Deference

HCD has authority to find that a local government's actions do not substantially comply with the HAA or Housing Element Law, but until now, few courts had determined how much deference should be afforded HCD's interpretation of those laws.

The court in La Cañada Flintridge held that, because HCD is mandated by statute to determine whether a housing element substantially complies with Housing Element Law, HCD's determination regarding substantial compliance "or lack thereof" is entitled to deference from the courts, although not binding. Rather, the courts independently review substantial compliance as a matter of law. Applying this standard, the court held that La Cañada's October 2022 Housing Element did not substantially comply with the Housing Element Law.

The Los Angeles decision reached the same conclusion. The court highlighted formal letters from HCD to various jurisdictions that emphasized HCD's position that a jurisdiction is not in compliance with Housing Element Law until the date of HCD's letter finding the adopted housing element in substantial compliance. While acknowledging that HCD's views are not binding, and that courts have the final say in interpreting statutes, the court noted that agency interpretations are given weight when they are reasonably based. The court concluded that Los Angeles had not successfully demonstrated HCD's position on the timing of compliance for housing elements to be unreasonable, effectively endorsing HCD's position on the requirement for post-adoption certification. The Redondo Beach decision also notes that HCD's statements about the Builder's Remedy are entitled to deference because HCD is the agency with special familiarity with the legal issue.

These decisions provide examples of courts holding that HCD's technical assistance letters are persuasive authority in disputes concerning laws it can enforce.

Why These Trial Court Decisions Matter

These trial court decisions address questions that have plagued applications using the Builder's Remedy in many jurisdictions. All three decisions concurred with HCD guidance that (1) housing element substantial compliance does not occur until HCD certifies an adopted housing element and (2) an SB 330 preliminary application vests housing element noncompliance for the duration of application processing. The decisions also held that reviewing courts should defer to HCD's substantial compliance findings and interpretations. Additionally, the decisions provide a roadmap for challenging a jurisdiction's refusal to process a Builder's Remedy project relatively early in the application process. The additional clarity provided by these decisions should reduce wrongful opposition to the Builder's Remedy. While offering important guidance, however, these trial court decisions do not constitute precedent binding on other courts.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.