In this series of Insights, we delve into why data cleanup efforts so often fail, despite organizations' desire to get rid of data they no longer need.

We're addressing the following five reasons that most commonly prevent organizations from effectively implementing data cleanup.

In part one of this series, we looked closely at the first of the reasons why data cleanup fails: accountability. We saw that ensuring the alignment between organizational and real-world accountability was critical in order for organizations to drive data cleanup from the top down.

In this post, we examine the second reason: buy-in.

Unpacking the Types of Buy-in

Although most people would agree that buy-in is important for Information Governance initiatives, we need to distinguish between two types of buy-in: individual and organizational.

- Individual buy-in depends on what each organizational stakeholder perceives as their "win" for getting on board with Information Governance. This concept aligns closely with the recent New York Department of Financial Services (NYDFS) amendments, which now require both the CISO and the senior executive officer to certify compliance. This change underscores the personal accountability of key figures in an organization, directly linking their role to the governance of information and cybersecurity.

- Organizational buy-in depends on aligning proposed Information Governance changes with corporate goals and objectives. The challenge here, as highlighted by the NYDFS amendments, is connecting Information Governance to operational goals rather than just top-down corporate strategies. For example, the amendments introduce specific requirements for incident response planning and risk assessments, directly tying Information Governance to operational effectiveness and compliance. By demonstrating how Information Governance contributes to operational goals like risk management, compliance with regulations (e.g., NYDFS, California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA)) and avoiding potential legal and financial repercussions, Information Governance can be positioned as a critical component of organizational strategy.

Which Type of Buy-in Matters More for Information Governance?

Individual buy-in is the easiest of the two to gain, but it has some complexities. First, it's predicated on Information Governance meeting the "What's in it for me?" (WIIFM) test? Information Governance needs to make an individual look good with leadership and achieve their stated objectives. Beyond that, to gain buy-in with individual stakeholders, Information Governance needs to determine how each individual views personal success and seek, as far as possible, to give them that success, e.g., doing the right thing, making money, maintaining the status quo, etc.

If you ignore the motivating factors of your key Information Governance stakeholders, you risk failing, not because your ideas weren't sound, but because your stakeholders weren't on board.

Organizational buy-in poses additional challenges: you first need to align with the overall corporate strategy to have any chance of gaining support. Given the often vague and politicized context of corporate strategy, this is no small task, but it's the first hurdle. It can be challenging to connect Information Governance activities to typical corporate strategic goals such as growth, corporate responsibility and sustainability, but doing so is critical to gaining support for Information Governance.

The best way to do so is to avoid trying to connect Information Governance directly to top-down corporate strategic goals and instead connect Information Governance to more operational goals and objectives, i.e., the funded operational initiatives that are already in flight to help business units align with corporate strategy. The NYDFS amendments, for instance, create a new category of 'Class A' companies with increased audit and reporting responsibilities, directly linking Information Governance to operational and financial metrics. There can be severe financial and reputational consequences of inadequate Information Governance, reinforcing the need for robust governance systems. To gain organizational buy-in, Information Governance needs to demonstrate how it contributes materially to operational goals, such as increased revenue, EBITA (earnings before interest, taxes and amortization), sales or market share.

Short of these direct offensive benefits of Information Governance, which may not be possible in all cases to quantify and demonstrate, you can also educate the board of directors on their personal accountability for compliance with laws and regulations such as CPRA and NYDFS. The recent regulatory focus on individual accountability makes it clear that non-compliance can have serious personal consequences for board members. Once leadership is reminded of this, they will more likely be on board and buy in to your Information Governance efforts to shield them from these negative consequences.

Gaining Widespread Support

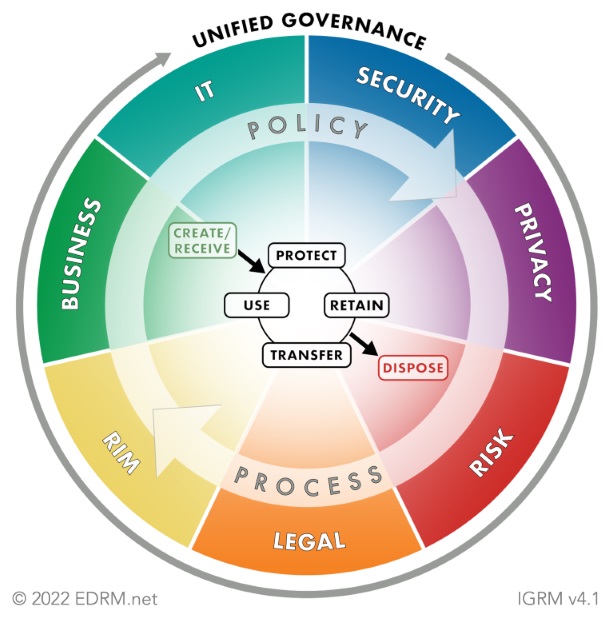

So, once you get top-level buy-in for Information Governance, how do you solidify that through the entire organization? The most proven way is to adopt a true Information Governance framework, such as the Information Governance Reference Model (IGRM). As shown in the figure below, the IGRM includes all relevant stakeholders, organized around information risk, information value and the cost of governing it. This encourages the inclusion of a wide range of perspectives and interests—making a narrow, siloed approach to Information Governance that benefits only some of the organization less likely.

Information Governance Reference Model

Balancing Value, Risk and Cost

The Information Governance Reference Model (IGRM), or something similar, is needed because Information Governance requires cross functional stakeholders to all agree on how to address the enterprise risk of information, across and between their individual concerns. Left to their own devices, litigation, records and information management (RIM), privacy, cyber, information technology (IT) and the business all have differing opinions on data risk and how best to address it—and these differences lead to stalemate and gridlock: organizations end up keeping information forever.

Adopting an Information Governance framework like the IGRM isn't enough by itself to break this stalemate: the organization also needs to assign organizational accountability for Information Governance in line with real-world accountability, that is, the person who external parties such as regulators and courts would hold accountable at the enterprise level. Only in this way will the person who will feel the weight of real-world enforcement feel the weight of organizational risk and make the changes necessary to address that risk. After all, if an executive has to explain to the Office of Civil Rights (OCR) or the CA Attorney General their Information Governance practices in the event of a regulatory action, they will work to ensure that the organization's policies and procedures are being followed.

What Does an Effective Information Governance Function Look Like?

First, it has representation for all the functions on the IGRM "wheel" above, that is:

- IT

- Security

- Privacy

- Risk

- Legal

- Records and Information Management

- Relevant Business Stakeholders

Without this wide organizational support, Information Governance fails because Information Governance relies on all these perspectives to make good decisions about managing the organization's information. Beyond this, Information Governance needs the clout to make decisions, i.e., organizational top-level support and decision-making authority. Without this, Information Governance makes recommendations, not decisions. And given the regulatory and legal stakes involved in Information Governance, this is untenable—if an organization wants to truly address Information Governance risk. If Information Governance has the decision-making clout needed, and if the wider organization recognizes the legal and regulatory risk Information Governance reduces, resources and funding should be forthcoming: Information Governance should have the people and dollars it needs to manage information properly to reduce all the risk that information poses to the organization.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.