INTRODUCTION

Across a wide range of industries, including advertising, banking, telecommunications, manufacturing, transportation, life sciences, waste management, defense, and agriculture, the use of AI and interest in its diverse applications are steadily increasing. Businesses are turning to AI systems, and the related technology of machine learning, to increase their revenue, quality and speed of production or services, or drive down operating costs through automating and optimizing processes previously reserved to human labor. Government and industry leaders now routinely speak of the need to adopt AI, maintain a "strategic edge" in AI innovation capabilities, and ensure that AI is used in correct or humane ways.

Yet the recent surge of interest in AI sometimes obscures the fact that it remains ungoverned by any single common body of "AI law"—or even an agreed-upon definition of what AI is or how it should be used or regulated. With applications as diverse as chatbots, facial recognition, digital assistants, intelligent robotics, autonomous vehicles, medical image analysis, and precision planting, AI resists easy definition, and may implicate areas of law that developed largely before AI became prevalent. Because it is an intangible process that requires technical expertise to design and operate, AI can seem mysterious and beyond the grasp of ordinary people. Indeed, most lawyers or business leaders will never personally train or deploy an AI algorithm—although they are increasingly called on to negotiate or litigate AI-related issues.

This White Paper seeks to demystify AI for nontechnical readers, and reviews the core legal concepts that governments in several key jurisdictions—the European Union, China, Japan, and the United States —are developing in their efforts to regulate AI and encourage its responsible development and use. Although AI legal issues facing companies will often be specific to particular products, transactions, and jurisdictions, this White Paper also includes a checklist of key questions that in-house counsel may wish to address when advising on the development, use, deployment, or licensing of AI, either within a company or in the transactional context. Ultimately, governments are implementing divergent and sometimes conflicting requirements. This scenario, which calls for patient review and a strategic perspective by regulated parties, rewards an ability to explain technical products to regulators in clear, nontechnical terms.

WHAT IS AI?

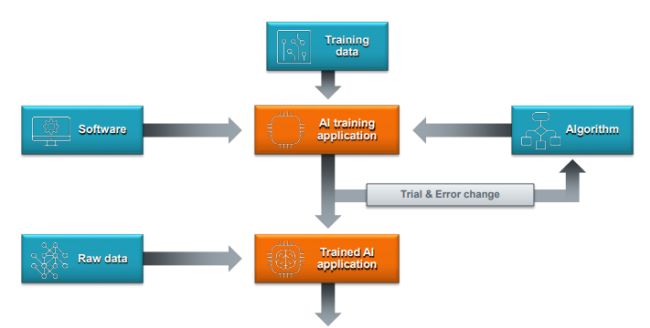

AI comprises complex mathematical processes that form the basis of algorithms and software techniques for knowledge representation, logical processes, and deduction. One core technology behind AI is machine learning, in which AI models can be trained to learn from a large amount of data to draw correlations and patterns allowing such models to be used in processing and making autonomous decisions, for example.

Key to each AI is its "objective function"—the goal or goals that its developers have designed it to achieve. This objective function can vary widely—from identifying molecules with likely antibiotic properties, to predicting where and when inputs in a transportation or manufacturing system will be needed, to spotting potential safety or security threats, to generating text, sound, or images that meet certain specifications. To learn to achieve this objective function, AI models can be trained using large data sets—with varying degrees of human oversight and feedback—learning to identify and make predictions based on patterns, likenesses, and fundamental attributes, including ones that humans may never have conceptualized or perceived. The AI is then prompted to apply the model it has honed during training to a real-life situation, where it executes its task. This latter activity is often referred to as "inference."

ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE (AI) COM

AI components typically comprise data (both training data for training and raw data for inference) and software processes to execute complex algorithms.

When trained and applied correctly, AI-based technology can unlock tremendous gains in productivity—enabling results or insights that would otherwise require prohibitively long periods of time to achieve by means of human reason alone, or even by humans using traditional computing techniques. In some cases, AI can be applied to replace or augment "rote" tasks that a person would otherwise perform much more slowly. In other cases, AI can generate text (including computer code, or responses to basic customer queries), sound, or images (including aspects of architectural or mechanical designs) that either replace the need for human input or serve as a first draft for human review. Often, a human mind, informed by AI inputs, analysis, and recommendations, can home in faster on a key range of options (pharmaceutical, strategic, etc.) warranting closer study.

In many industries, integrating AI-based technology is considered the key to secure long-term competitiveness. Most industrial countries have already started the race for world market eadership in AI technologies through various means such as public funding. In addition, governments seek to support AI's growth through a legislative framework that allows the technology to develop and optimize its potential.

However, as many governments and analysts have noted, the benefits of AI systems can also come with risks. For example, AI can contribute to the creation of "echo chambers" that display content based only on a user's previous online behavior and thereby reinforce their views and interests or exploit their vulnerabilities. AI applications are also increasingly used in objects routinely interacting with people, and could even be integrated in the human body, which can pose safety and security risks.

Governments seeking to regulate AI aim to build citizen trust in such technology while limiting potentially harmful applications. Yet different governments, and different agencies within the same government, sometimes have different concepts of what constitutes an appropriate manner of training and applying AI. What one authority sees as a feature, another may see as a bug. Further, they—and regulated publics—may disagree on the ideal relative weight to place on key considerations such as privacy, transparency, liberty, and security. As governments apply divergent perspectives to this technically complex (and often inherently multijurisdictional) area, regulated parties face a complex, sometimes contradictory body of regulatory considerations that are themselves changing rapidly. Training, deploying, marketing, using, and licensing AI, particularly if these activities occur across multiple jurisdictions, increasingly requires a multidisciplinary and multijurisdictional legal perspective.

HOW IS AI REGULATED?

While many laws already apply to AI, ranging from IP protection to competition law and privacy, AI's rapid expansion has alerted legislators worldwide, leading to updating legal and regulatory frameworks and, in some cases, creating entirely new ones. These global legal initiatives generally aim at addressing three main categories of issues:

- First, legislation and regulations aim to foster AI deployment by creating a vibrant and secure data ecosystem. Data is required to train and build the algorithmic models embedded in AI, as well as to apply the AI systems for their intended use. In the European Union, AI's hunger for data is regulated in part through the well-known GDPR; additionally, a proposed Data Act facilitating data access and sharing is underway. In comparison, the United States has taken a more decentralized approach to the development and regulation of AI-based technologies and the personal data that underpins them. Federal regulatory frameworks—often solely in the form of nonbinding guidance—have been issued on an agency-by-agency and subject-by-subject basis, and authorities have sometimes elucidated their standards in the course of Congressional hearings or agency investigations rather than through clearly proscriptive published rules. The People's Republic of China, for its part, has expanded its data security and protection laws, with a particular emphasis on preventing unauthorized export of data. While the central government promulgates generally applicable laws and regulations, specialized government agencies have provided regulations specific to their respective fields, and local governments are exploring more efficient but secure ways to share or trade data in their areas, such as setting up data exchange centers.

- Second, regulators in multiple jurisdictions have proposed or enacted restrictions on certain AI systems or uses assessed to pose safety and human rights concerns. Targets for such restrictions include AI robots capable of taking lethal action without a meaningful opportunity for human intervention, or AI social or financial creditworthiness scoring systems that pose unacceptable risks of racial or socio-economic discrimination. In the European Union, the sale or use of AI applications may become subject to uniform conditions (e.g., standardization or market authorization procedures). For instance, the proposed EU AI Act aims to prohibit market access for high-risk AI systems, such as AI systems intended for the "real-time" and "post" remote biometric identification of natural persons. Members of Congress in the United States have advanced legislation that tackles certain aspects of AI technology, though in a more piecemeal, issue-focused fashion. For instance, recently passed legislation aims to combat the effect of certain applications of generative adversarial networks capable of producing convincing synthetic likenesses of individuals (or "deepfakes") on U.S. cybersecurity and election security. The PRC and Japan have not yet issued mandatory laws or regulations restricting application of AI in any specific area for concerns such as discrimination or privacy. But similar to the United States, China regulates various aspects important to the realization and development of AI, such as data security, personal information protection, and automation, among others.

- Third, governments are just beginning to update traditional liability frameworks, which are not always deemed suitable to adequately deal with damages allegedly "caused by" AI systems due to the variety of actors involved in the development, interconnectivity, and complexity of such systems. Thus, new liability frameworks are under consideration, such as establishing strict liability for producers of AI systems, in order to facilitate consumer damage claims. The first comprehensive proposal comes from the European Union's new draft liability rules for AI systems, aimed at facilitating access to redress for asserted "victims of AI," through easier access to evidence, presumption of causality, and reversal of the burden of proof.

Each of these will be further discussed in the next sections

To view the full article, click here

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.