Over the past several years, we have seen dramatic growth in patent applications for distributed ledger technologies such as blockchain. Most famously implemented by Bitcoin, these technologies are penetrating more and more sectors beyond fintech, including healthcare, autonomous transportation, supply chain management, and even IP enforcement. However, although more and more entities in more and more sectors are seeking patents for blockchain technologies, the blockchain patent "battleground" that has repeatedly been forecast has not yet materialised. This is largely because blockchain patent applications do not always result in readily enforceable patents and, even compared with other computer-implemented technologies, detecting, and proving infringement of blockchain patents is relatively difficult. Moreover, even when infringement is detected and provable, the fundamentally "distributed" nature of the technology often makes it uneconomical to bring suit.

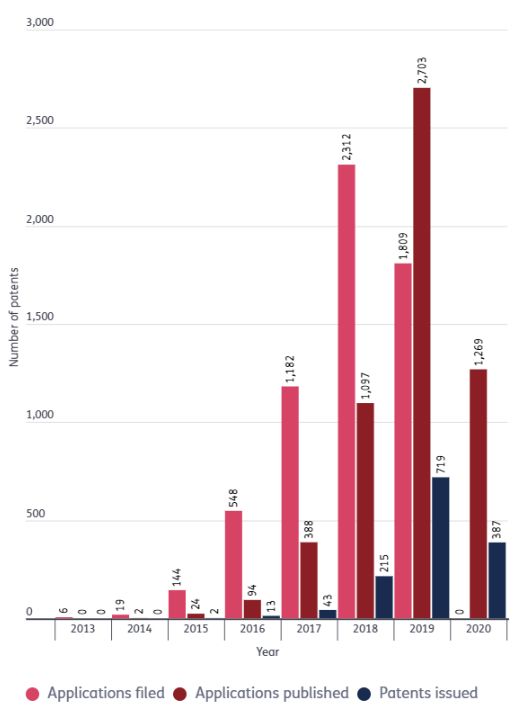

The first US patent applications1 using the term "blockchain"2 were filed in 2013 – five years after Satoshi Nakamoto's seminal paper on Bitcoin.3 Since that time (see figure 1), the number of US patent applications involving blockchain technologies has grown exponentially. At the time of writing, a total of 6,016 such applications are known to have been filed, of which 1,379 have been patented. To put this in perspective, however, during that same timeframe, there were about 37,000 US applications filed using the term "artificial intelligence", resulting in about 20,000 issued patents; and about 13,000 US applications filed using the term "autonomous vehicle", resulting in about 6,000 issued patents.

Figure 1: The number of blockchain-related patents filed, published or issued at the US Patent and Trademark Office between 2013 and April 2020

* Data is current as of 22 April 2020. However, applications with a priority date after 22 October 2018, may not have been published at time of writing.

The relatively slow grant rate for blockchain patents in the US is largely attributable to the USPTO's continuing struggle with patent eligibility under 35 USC section 101. At its core, blockchain technology is typically implemented by processors exchanging data in a peer-to-peer network. Even after the office loosened examination standards with the 2019 Revised patent subject matter eligibility guidance (revised guidance)4 – much to the benefit of applications on artificial intelligence and other computer-implemented technologies - USPTO examiners continue to reject many blockchain claims as being drawn to abstract "mental processes" that use technology only as a tool to speed the process. This is particularly true in the fintech area, where most blockchain patent applications are examined.

It is often possible to win examiners over by citing Example 41 of the revised guidance5 (holding a claim drawn to a "method for establishing cryptographic communications" to be patent eligible). However, the revised guidance does not include an example specifically directed at blockchain. (By contrast, China's National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA) recently amended its patent eligibility guidelines to include a training example holding a "communication method and device between blockchain nodes" to be patent-eligible.)6 Consequently, some US applicants are forced to address subject matter eligibility rejections by amending their claims to incorporate more of what patent examiners consider to be "technology"– typically by claiming more details of the network and environment and interactions between nodes in the network. However, these types of claim limitations make it much harder to prove infringement by distributed ledger technologies.

Even in comparison to other computer-implemented technologies, such as audio or video processing technologies, detecting infringement of blockchain patents is relatively difficult. This is because, unlike audio or video processing technologies – where infringing methods can often be detected based on an analysis of the input and output (or examination of interoperability standards) – the features of an (allegedly) infringing blockchain technology are often hidden from view. In particular, the details of blockchain data structure, smart contract operations, cryptography, and consensus algorithms may be reflected only in the server-side code. Without inspecting the actual source code implementing the features of the infringing technology, one may not be able to determine infringement with enough confidence to pull the trigger on an expensive patent suit.

In addition, "distributed" ledger technologies – by definition – involve interactions between distributed nodes in a computer network. Each of these nodes may perform only a part of the method claimed in the patent. As an added wrinkle, the nodes may be operated by different entities, in different countries. Each of these possibilities adds another hurdle that must be overcome before a blockchain patent owner can file suit. And all of them together increase the size of the first hurdle – the pre-litigation budget that must be approved to finance the investigation of the suspected infringement in the first place.

First, under US patent law, direct infringement occurs where all steps of a claimed method are performed by a single entity. When more than one actor is involved in performing the steps of a claimed method (so-called "divided infringement"), a court may find infringement only if the acts of the other entities are attributable to the accused infringer, such that a single entity remains responsible for the infringement. In Akamai Techs, Inc v Limelight Networks, Inc,7 the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit held that one entity may be held responsible for another's performance of a method step in two sets of circumstances:

" Where that entity directs or controls the other's performance; and

" Where the two entities form a joint enterprise. In either case, indirect infringement requires additional proofs of the business relationship between the two entities, making proof that much more difficult.

For example, if a first entity performs all but one step of a method in a blockchain patent, which is performed by a second entity, the patent owner needs to prove that the first entity (1) directs or controls the second entity's performance by proving that the second entity is an agent of the first, or (2) that there is a joint enterprise contract between the two. Such proofs are hard to come by before filing suit – thus making it that much less likely that a suit will be filed.

The solution to this first problem is to draw a circle around the core functions of a node, write the claims to cover the inputs to and outputs from that circle, and to hold to that line throughout prosecution. The difficulty here is that it's not always easy to predict how tightly to draw the circle, and (as explained above) it's not always easy to hold that line in the face of a rejection under 35 USC section 101.

Secondly, patents are territorial, even if blockchain technologies are not. In NTP, INC v Research in Motion, Ltd,8 the Federal Circuit held that a method claim was not infringed by a single entity that performed some steps in the US, but others in a foreign country. However, a corresponding system claim would be infringed if "control of the system is exercised and beneficial use of the system obtained" within the US. The solution to this second problem is to include system and device claims in addition to method claims. However, it is just as difficult to draw the circle around infringing devices and systems, as it is to draw the circle around the underlying method, and just as difficult to hold that line through prosecution.

Thirdly, US patent law allows the patent owner to join multiple defendants in a single suit only if the claim "aris[es] out of the same transaction, occurrence, or series of transactions or occurrences relating to the [infringement]", 35 USC section 299(a)(1). Notwithstanding the distributed nature of blockchain technologies, this standard should be relatively easy to meet where each of the defendants are links in the same (block)chain. However, it must be remembered that – even if joined in one suit – each additional defendant adds a marginal cost to the litigation, thus making it that much more difficult to bring suit against the smaller fish.

Finally,9 as with many other problems, the solution to all of the above is to work with counsel who is cognisant of these problems and just as creative in seeking their solution as the inventors of the underlying technology.

Footnotes

1. Now US patent nos 9,338,148 and 10,332,205.

2. Although not all relevant patents will use the term "blockchain", and some patents may use the term only in passing, its presence serves as a useful barometer to show the magnitude and growth in patent filings.

3. S, Nakamoto, Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System (2008).

4. 84 Fed Reg 50 (7 Jan 2019).

5. USPTO, Subject matter eligibility examples: abstract ideas (7 Jan 2019) at 14.

6. CNIPA, Announcement on amending the "Guide to patent examination" (No 343) (31 Dec 2019) at section 6.2, [Example 4] (in Chinese only).

7. 797 F.3d 1020 (Fed Cir 2015).

8. 418 F.3d 1282 (Fed Cir 2005).

9. Of course, there are many other issues to consider.

Originally published by Intellectual Property Magazine on June 1, 2020 .

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.