A Brief Legal History: Understanding Reissue Patents

Patent owners have the option to seek a broader scope of coverage for their invention by filing a continuation application with the United States Patent and Trademark Office while their original application is still pending. This allows them to include claims that extend to the full scope of the subject matter described in the original specification. However, once a patent is granted, changes to the scope of the claims can only be made through a vehicle call "reissue," which is subject to additional statutory limitations.

One of these limitations is the requirement that the reissue claims must be directed to the same invention as the original patent. This is known as the "original patent" requirement. The standard for satisfying this requirement is established in the U.S. Industrial Chemicals, Inc. v. Carbide & Carbon Chemicals, Corp., 315 U.S. 668 (1942). In this Supreme Court case, the original patent included a specification that stated water improved the efficiency of a certain reaction. However, after the patent was issued, the patent owner discovered that water was not actually necessary for the most efficient reaction. A reissue patent was obtained with a substitute specification and new claims, indicating that the reaction could take place with or without added water.

The Supreme Court ruled that for a reissue patent to be valid, it must fully describe and claim the same invention intended to be secured by the original patent. It must be clear from the face of the reissue patent that what is covered by it was intended to be covered and secured by the original patent. In this case, because the original patent treated the introduction of water as a necessary step, its absence in the reissue claims rendered those claims invalid. The Supreme Court also clarified that simply suggesting or indicating a new invention in the original patent specification does not automatically meet the requirements of a reissue claim. The Supreme Court further explained that a reissue claim does not meet the "original patent" requirement merely because the newly claimed invention could have been claimed in the original patent and was supported by the original specification.

In summary, applicants have the ability to expand the scope of their patent claims while their application is pending, but once a patent is granted, changes to the claims can only be made through a reissue patent, which must satisfy the "original patent" requirement. This requirement ensures that any changes made are consistent with the original invention disclosed in the original patent. With this background, let's turn our attention to the case at hand.

The Current Case: An In-depth Analysis

The Federal Circuit affirmed the Board's decision that the reissue claims do not meet the "original patent" requirement because the specification, on its face, does not explicitly and unequivocally describe the invention as recited in the reissue claims. In re Float'N'Grill LLC, Case No. 22-1438 (Fed. Cir. July 12, 2023) (Prost, Linn, Cunningham, JJ.)

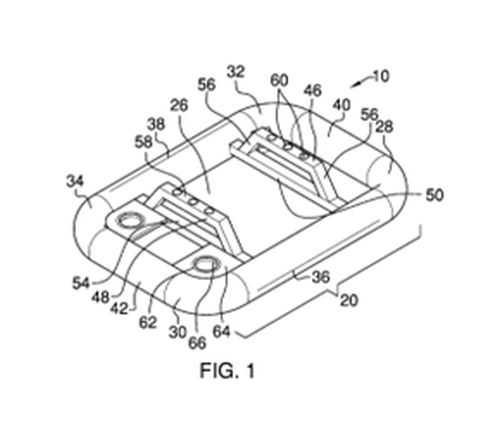

U.S. Patent Number 9,771,132 ("the '132 patent") describes a floating device that allows users to grill food while in a body of water. This apparatus, shown in Figure 1, includes a float 20 and two grill supports 46, 48. Each support includes a base rod 50 and an inverted U-shaped upper support 52 attached to the top surface of the base rod 50. The upper support 52 also contains magnets 60 in its middle segment. To secure a portable outdoor grill, the flattened bottom side 74 of the grill 76 can be attached to magnets 60 on each grill support 52. The patent does not mention that magnets 60 are option and does not provide any other method or component for securing the grill.

The central issue in this case revolves around the importance of the "plurality of magnets" in the original patent. Claim 1 of the patent is specifically focused on the embodiment described in the written description, akin to a "picture claim." The language of claim 1 originally matched the description of the plurality of magnets exactly. This claim was never rejected during the application process and was accepted as originally presented.

After the issuance of the '132 patent, Float'N'Grill LLC ("FNG") believed that it had claimed less than it was entitled to in the original patent. It filed a reissue application seeking additional new claims. These new claims did not contain the specific "plurality of magnets" limitation, but rather made a more general reference to the removable securing of a grill to the float apparatus. The Examiner rejected the claims for failing to meet the reissue standard. The Examiner argued that the original patent disclosed a single embodiment of a floating apparatus using a plurality of magnets, which was considered a critical element for a safe and stable attachment between the floating apparatus and the grill. Since the new claims did not include this crucial limitation, they were determined to not satisfy the requirements of the original patent. The Board upheld the Examiner's rejection. FNG appealed.

The Federal Circuit agreed with the Board's determination that the reissue claims in this case do not meet the original patent requirement. The original patent describes a specific embodiment of the invention, involving a grill support with magnets for securing the grill to a float. The reissue claims eliminate this component, which is the only structure disclosed for safely and securely attaching the grill. The original patent does not mention any alternatives or variations for achieving this function. The Board found that magnets are essential to the invention, as they provide a unique method of attachment compared to conventional fasteners. The specification does not suggest any alternative mechanisms or indicate that the magnets are a substitute for other removable fasteners. Therefore, the plurality of magnets remains the only disclosed method for securely attaching the grill to the float.

FNG argued that the existence of multiple magnets is not an essential feature of the original patent, similar to the tapering of metal tips in the Peters case. FNG further argued that a skilled person in the field would understand that the specific means by which the floating apparatus supports the grill is unimportant. The Court disagreed.

Turning its attention to Peters case, the Court noted that in that case the patented invention was a display device with front and back walls separated by support elements, each equipped with a metal tip that had a tapered cross-section. 723 F.2d 891, 92 (Fed. Cir. 1983). The purpose of these metal tips was to secure the support elements and prevent lateral movement of the channels formed by them. However, in the reissue patent, Peters removed the requirement for the tapered shape of the metal tips. The Board then rejected the reissue claims, stating that they were not supported by the original disclosure. However, the Court disagreed and explained that the original specification did not indicate that the tapered shape of the tips was essential or critical to the operation or patentability of the invention. The Court further emphasized that a skilled person in the field would understand that the tapered shape of the tips was not essential or critical according to the original disclosures. However, in the case at hand, the requirement for a plurality of magnets to fulfill the claimed removably securing function is not superficial but is the specific embodiment disclosed in the patent.

Finally, FNG argues that Revolution Eyewear v. Aspex Eyewear, Inc., 563 F.3d 1358, 1366 (Fed. Cir. 2009) and In re Rasmussen, 650 F.2d 1212, 1215–16 (CCPA 1981) hold that if the original specification would have supported the reissue claim omitting the limitation, then the original patent requirement is satisfied. FNG is incorrect. The requirement is not whether the original specification supports the reissue claims, the requirement is whether the specification, on its face, explicitly and unequivocally describes the invention as recited in the reissue claims.

Practice Tips:

Tip 1: This case serves as a valuable reminder to practitioners about the significance of avoiding definitive language and instead using optional language in their work. By incorporating phrases like "may be," "may include," and "in one specific example," practitioners can enhance the effectiveness of their applications. It is crucial for practitioners to also consider and include alternative implementations of the invention within their applications and not just the best mode the inventor has conveyed to them. In this particular case, upon reviewing the application, it becomes evident that it lacks both optional statements and alternative implementations. The Board and Federal Circuit have both taken note of this, as they observed that the plurality of magnets described in the application were deemed crucial, and the specification did not provide any alternatives to them.

Tip 2: The Federal Circuit walked a fine line differentiating this case from the Peters case. Regardless, it is important to note that the standard for reissues is not just about whether the reissued claims are backed by the original specifications. Instead, it focuses on whether the reissue claims truly represent the invention the applicant was seeking.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.